“Not real food”? Says Eddie Abbew. A closer look at claims about tempeh, soy, and men’s health.

Claim 3: “I don’t believe tempeh is food.” “If you want to improve your health in general then avoid tempeh because that’s not food in my opinion.”

Fact-Check: This claim misrepresents both nutrition science and cultural food traditions. While it is framed as a personal opinion, it reflects a broader misunderstanding of how foods are classified, and how dietary diversity supports health.

What is “real” food?

A lot of Eddie’s content revolves around the idea of “real” food, and his criticism of the food system which pushes items that, in his view, are disguised as food but do not support optimal health. This is based on valid concerns around the prevalence of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) in our diet, which indeed dominate supermarket shelves (source). But tempeh isn’t one of them.

Foods are commonly categorised using the NOVA classification system, which groups foods by their level of processing: from unprocessed or minimally processed (Group 1), to ultra-processed foods (Group 4), which tend to be energy-dense, nutrient-poor, and heavily altered through industrial processing.

It might seem, at first, that when Eddie Abbew refers to “real” food, he means foods that are unprocessed or minimally processed. But when you look more closely at his content, the definition appears much narrower, limited to a handful of primarily animal-based, whole foods.

That’s where the problem lies: this framework promotes an overly restrictive eating pattern that labels many health-promoting foods as unacceptable.

Tempeh is very much food: nutritionally, culturally, and historically.

Tempeh has only started to gain popularity in the UK in recent years, and therefore might still be unfamiliar to some. But it has been a staple in Indonesian cuisine for centuries.

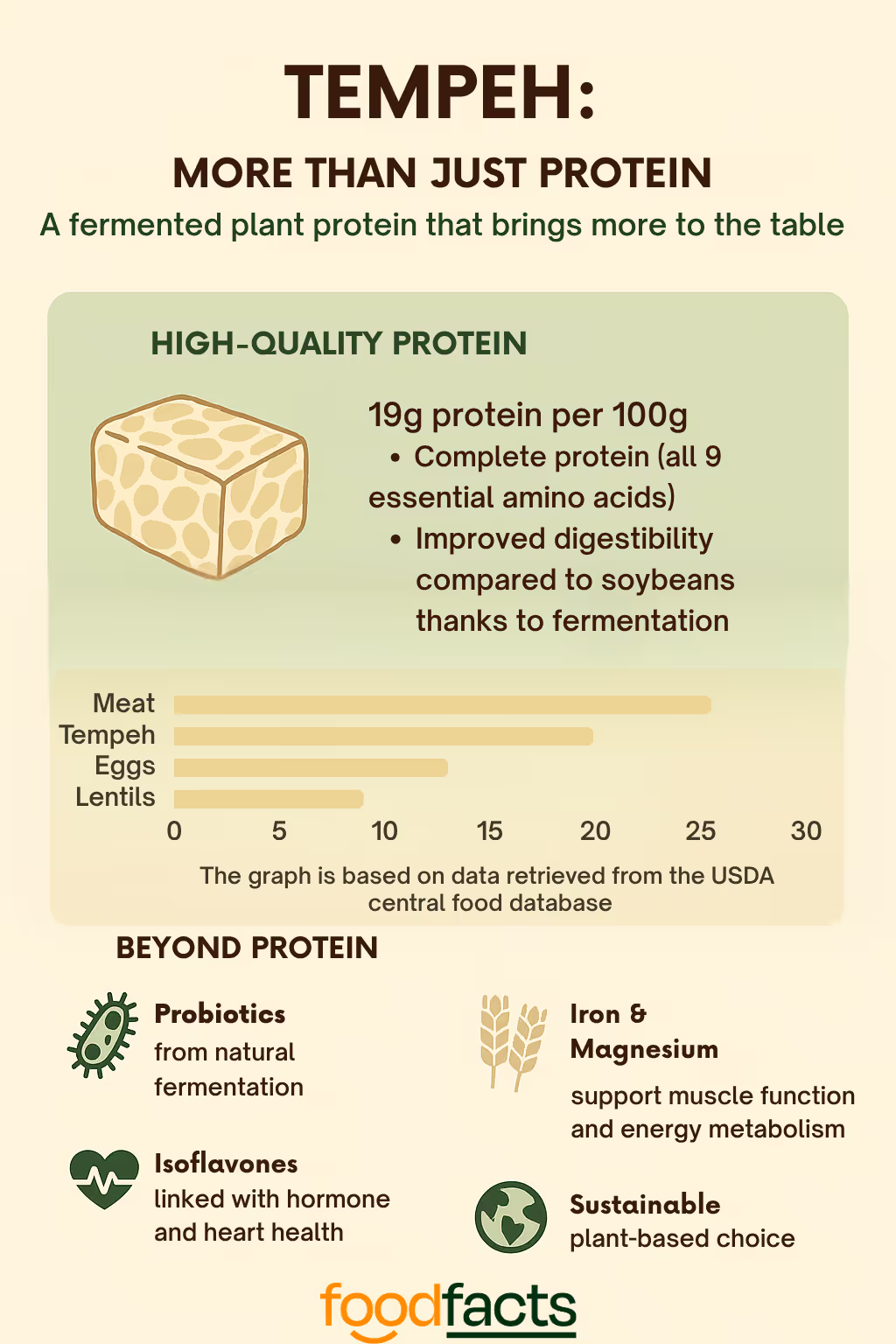

Tempeh is made by fermenting cooked soybeans with a natural starter culture. This fermentation process not only preserves the soybeans but also enhances their nutritional value and digestibility, increasing protein availability, reducing antinutrients, and introducing gut-friendly compounds like probiotics (source).

It offers a great example of beneficial processing, in this case, fermentation, that improves both nutrient bioavailability and gut health (source). Indeed part of the issue with Eddie’s narrow categorisation of “real” food is that it also fuels distrust in any form of food processing, ignoring its benefits to make food safe (like pasteurisation), or to enhance nutrition.

Tempeh’s place in a balanced diet

Rather than thinking of foods as “good” or “bad,” it’s more helpful to view them as part of a diverse nutritional toolbox. Tempeh offers:

- High-quality protein (about 19g per 100g);

- Fibre, iron, magnesium, and other micronutrients;

- Probiotics from natural fermentation;

- Isoflavones that may benefit heart and hormonal health;

- A low-saturated-fat alternative to processed meat.

The purpose of tempeh is not to replace all animal-protein. But it can be an excellent option for people who wish to reduce meat consumption, for those concerned about managing cholesterol or cardiovascular health, and for anyone seeking more fibre and gut-friendly diversity.

Final Take Away

While it’s important to question food marketing and make informed choices, much of what circulates online fuels unnecessary fear around certain foods or ingredients. Often, foods are demonised not because of evidence, but because they don’t align with the dietary views promoted by some content creators.

And this matters. It’s not just a question of scientific accuracy: it has real implications for public health. Research consistently shows that increasing plant protein in the diet is associated with a lower risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and all-cause mortality. At the same time, many people in the UK and other countries fall well below recommended fibre intake.

Tempeh is a minimally processed food that supports dietary diversity, and a great way to increase intake of both plant protein and fibre. Discouraging its consumption not only misrepresents nutrition science, it also undermines public health efforts to promote access to affordable, nutrient-dense foods that support long-term health.

We have contacted Eddie Abbew and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Claim 2: “Soya has been known to raise oestrogen levels and lowers testosterone in men especially.”

Fact-Check: This claim is not supported by evidence.

Phytoestrogens vs. human estrogen: where the confusion starts

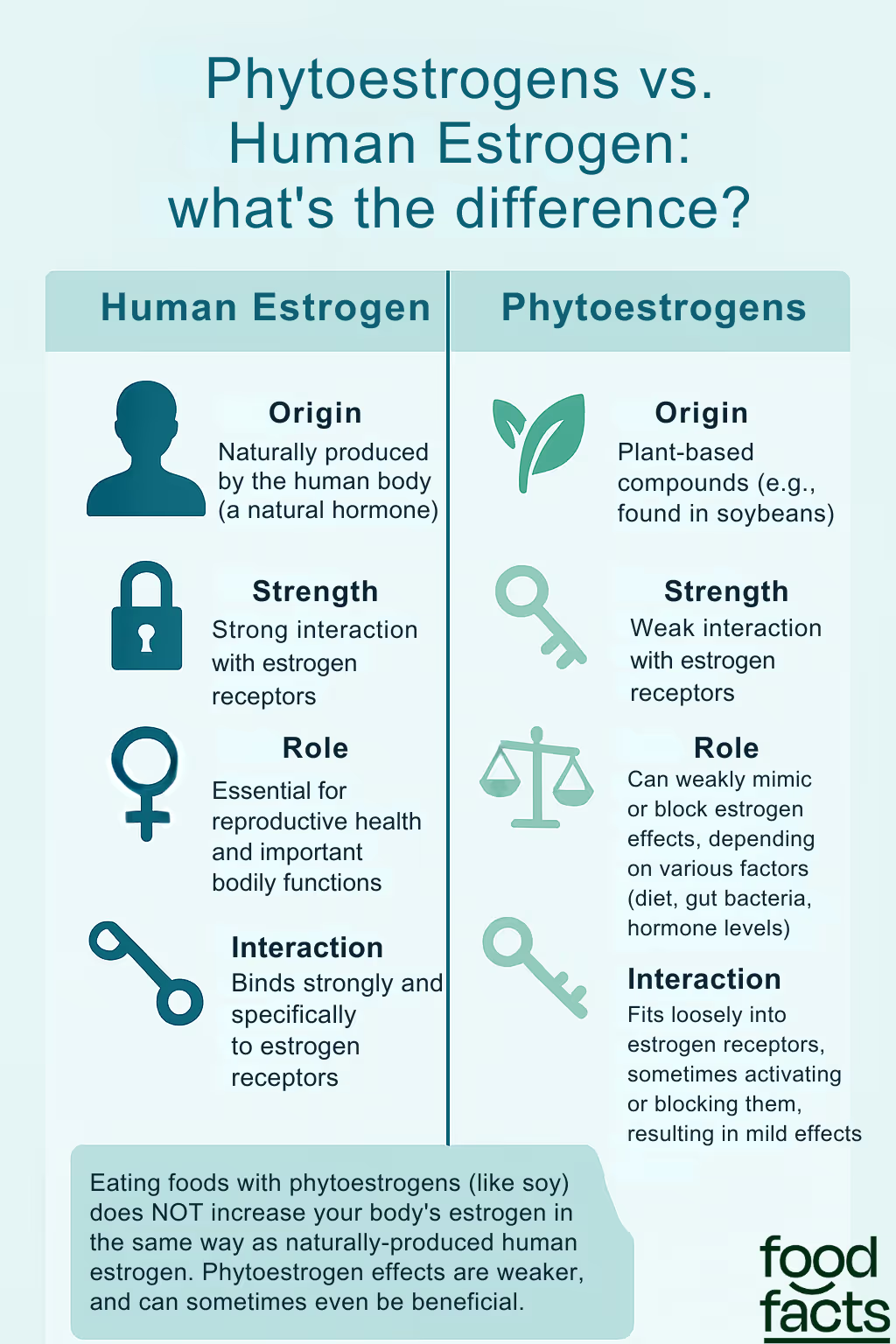

Phytoestrogens, like those found in soy, are often confused with human estrogen, but they are quite different. Human estrogen is a hormone naturally produced by the body that plays a key role in reproductive health and other functions. Phytoestrogens, on the other hand, are plant compounds that only look a bit like estrogen and can weakly interact with the body’s estrogen receptors (source). Because they are much weaker than human estrogen, phytoestrogens can sometimes mimic its effects, but they can also block estrogen’s action depending on the situation. The way phytoestrogens work in the body is complex and depends on factors like how much is eaten, a person’s gut bacteria, and their own hormone levels (source).

Importantly, eating foods with phytoestrogens, such as soy, does not mean the body’s estrogen levels will rise in the same way as if it produced more of its own hormone. In fact, the effects of phytoestrogens are generally much milder and can even be beneficial for some health conditions according to this 2024 study.

So, while phytoestrogens and human estrogen can both interact with the same receptors, they are not the same and do not have the same strength or effects in the body.

The actual effects of soy on male hormones

The claim that soy raises estrogen (oestrogen) levels and lowers testosterone in men is not supported by the best available clinical evidence. Where do these claims then come from?

Some small or short-term studies have reported minor reductions in testosterone or changes in other hormone levels, but these effects are generally modest, inconsistent, and not linked to clinically meaningful outcomes (source).

Large, high-quality meta-analyses of human studies have found that neither soy foods nor soy isoflavone supplements significantly affect testosterone, free testosterone, estradiol (a form of estrogen), or other key sex hormones in men, regardless of dose or duration of intake according to this 2020 meta-analysis. These findings have been confirmed again and again in research. Even men who eat a lot of soy—far more than most people do—show no signs of hormonal changes or "feminising" effects.

Animal studies and the phenomenon of ‘cherry picking’

Many of the concerns and claims about soy and hormones come from animal studies, especially those done on rats and mice. In these studies, the animals were often given very high doses of soy compounds - much more than a person would ever get from eating tofu, soy milk, or other soy-based foods like tempeh (source). As a result, outcomes observed in animals, such as modest oestrogen‑like activity, do not reliably translate to effects in humans.

Overall, the consensus from robust human research is that soy consumption does not feminise men or disrupt their reproductive hormones.Influencers on social mediasuch as Eddie Abbew frequently rely on selective citation—also known as cherry‑picking—where only studies fitting a particular narrative are highlighted, while the broader, more rigorous evidence is ignored. For example, a 2007 small-scale trial observed a minor decrease in testosterone among 12 men consuming 56 g per day of isolated soy protein (for 4 weeks), but this dose far exceeds typical diets and the effect was neither consistent nor sustained (in a sample of only 12 individuals). However, that single finding has been disproportionately cited, even though larger and better-quality studies have found no real effect.

Claim 1: “Soya beans are not the best source of protein [...] You are not getting the nutrients that you think you’re getting from the protein in [tempeh].”

Fact-Check: Soy is a high-quality source of protein.

This claim is misleading because of its framing: ranking protein sources in isolation oversimplifies nutrition and can lead to unnecessary restrictions.

How is protein quality assessed?

Scientists evaluate protein based on two key factors: whether it contains all nine essential amino acids, and how easily our bodies digest and absorb them. Tools like PDCAAS (Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score) and the newer DIAAS (Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score) score proteins on these criteria (source, source). A higher score indicates a protein that’s more useful to the body.

Soy protein performs well by both measures.

It’s one of the few plant proteins that’s considered “complete,” and it scores highly on both PDCAAS and DIAAS (source). This means soy delivers all the amino acids your body needs to build and repair tissues. In other words, you are getting quality protein when you eat soy, whether it’s in the form of tofu, tempeh, or edamame.

Should we rank protein sources?

It all depends on context. Understanding protein quality is essential to inform nutritional guidelines, and it helps consumers to make informed decisions.

But on social media, rankings are often used to promote restrictive diets, based on the argument that the foods that score lower in one area are not worth eating. This can be problematic because it fuels misunderstanding about how nutrition works and can lead to unnecessary restrictions.

Health isn’t about consuming the “highest scoring” protein in isolation, it’s about the overall pattern of what you eat. Some of the healthiest dietary patterns (for example the Mediterranean Diet) include a variety of protein sources, plant and animal, making them accessible to all through a focus on balance and variety. A better approach is to embrace variety, consider context (e.g., allergies, preferences, accessibility, environmental impact), and aim for adequate protein intake overall.

As research consistently points to associations between higher intake of plant protein and lower risk of all-cause mortality, the suggestion that we should exclude plant sources of protein contradicts scientific evidence and could negatively affect health.

Always fact-check nutrition advice that categorises food as either real or fake, with no middle ground. Such oversimplifications often miss the big picture of what constitutes a well-balanced diet.

Influencer Eddie Abbew recently posted a video on social media in which he suggests that tempeh isn’t “real” food. He claims that soya is not the best source of protein, and that it has been known to increase oestrogen levels and lower testosterone, especially in men.

Keep reading to find out if those concerns are supported by evidence.

Full Claim: “I don’t understand why anyone would stop eating nature made protein like meat, poultry, fish, eggs, to eat this nonsense. Personally, I don’t believe tempeh is food. Soya beans are not the best source of protein - it doesn’t matter what claims they make on the product. You are not getting the nutrients that you think you’re getting from the protein in this product. Soya has been known to raise oestrogen levels and lowers testosterone in men especially. If you want to increase testosterone as a man, eat eggs especially and, if you want to improve your health in general then avoid tempeh because that’s not food in my opinion.”

Eddie Abbew’s statements dismiss the nutritional value of soy-based foods like tempeh, mischaracterise soy’s impact on hormones, and promote an overly narrow definition of what constitutes “real” food. Research shows that soy is a high-quality protein source. It is nutritionally complete, widely accessible, and beneficial to health. Including tempeh in your diet supports both nutrient adequacy and long-term wellbeing, especially when part of a varied, balanced eating pattern.

Even when clearly framed as opinion, nutrition advice shared with over 4 million followers carries weight. When those views discourage foods like plant proteins, despite strong evidence of their health benefits, it’s important to offer clarity and context.

How AI is changing the farm: a double-edged sword for animals

AI: The future of farming?

Imagine a future where animals on farms are continuously monitored by invisible, tireless guardians. Precision Livestock Farming (PLF) brings this vision into reality, using AI-powered sensors and algorithms to track animals' health and behavior, optimize feeding, and even predict disease outbreaks. From dairy cows to pigs and poultry, technology promises a revolution.

At farms like Connecterra's "Ida", sensors monitor cows' activity patterns, quickly identifying illness signs long before a human might notice. This AI-enabled detection means quicker intervention, potentially reducing suffering and improving animals' lives.

However, while this tech-driven utopia seems promising, there's another side to the story that deserves our attention.

Current reality: The hidden cruelty of industrial farming

The reality facing farmed animals today is grim. Chickens are routinely crowded into barns by the thousands, living in their waste and unable to perform natural behaviors like perching or foraging. Pigs are commonly confined in tiny gestation crates, unable even to turn around for most of their lives. Dairy cows, repeatedly impregnated and separated from their calves shortly after birth, are pushed beyond their physical limits, causing chronic pain and distress. These standard practices reveal an alarming disregard for animal welfare, driven largely by efficiency and profit.

Machines watching over lives: predictive analytics and health

AI-based predictive analytics are turning farms into hyper-efficient systems. Companies like Dilepix provide farmers with real-time data, ensuring precise feeding and managing breeding more effectively. By preemptively addressing health issues, fewer animals fall sick, which reduces unnecessary suffering.

Yet, these advancements may also inadvertently legitimize and entrench high-density, intensive animal farming—systems which inherently compromise animal welfare.

Resource optimization: Environmental gains, but at what cost?

AI promises greater efficiency and reduced environmental impacts by precisely managing resources. For instance, Smartbow’s monitoring systems reduce feed waste significantly, conserving vital resources and cutting emissions. It’s undeniably impressive and seems like a win-win scenario.

However, what looks like efficiency might simply enable the expansion of factory farming—potentially escalating the number of animals farmed, thus magnifying rather than minimizing their suffering and environmental harm.

Ethical concerns: The darker side of automation

Automation powered by AI could push animal farming toward a future with minimal human oversight. Animals could increasingly become mere data points, managed through screens and automated processes rather than direct human care. This dystopian scenario isn't just theory; it's already unfolding.

Consider automated milking systems by companies like Lely. While efficient, such technologies reduce direct human-animal interactions, neglecting animals' emotional and social needs, turning farms into clinical production lines.

The reinforcement of intensive practices

A troubling possibility is that AI will entrench intensive farming practices further. Technologies such as facial recognition for pigs and AI-powered egg-laying monitoring for hens enhance productivity but can inadvertently endorse cramped, stressful environments by making them economically viable. The technology itself isn't malevolent, yet it may inadvertently facilitate cruelty by optimizing systems inherently harmful to animal welfare.

Economic pressures and animal welfare

Farms often operate under significant economic pressure, and efficiency usually means profitability. Unfortunately, animals are frequently caught in this efficiency equation. AI systems designed primarily to enhance productivity might prioritize rapid growth and output at the cost of humane treatment. Profit-driven imperatives could dominate ethical considerations, sidelining welfare improvements in favor of economic gains.

Regulatory gaps and animal protection

Alarmingly, the rapid development of AI in farming has vastly outpaced regulatory frameworks, especially in regions where animal welfare laws are lax. Without stringent oversight, AI could amplify existing welfare issues, making farms more opaque and harder to regulate.

An alternative is possible

As an advocate for animal liberation, my greatest concern is that AI, despite its potential benefits, could inadvertently solidify our reliance on industrialized animal agriculture. Yes, precision farming may reduce certain types of suffering. Yet, the fundamental cruelty inherent in intensive animal farming—the confinement, the lack of natural behaviors, and the massive scale—is untouched, even potentially exacerbated by this technology.

Additionally, I firmly believe there is no ethical justification for farming animals at all, with or without technological improvements. There is simply no humane way to commodify living beings who experience pain, fear, and joy. The use of AI might make industrial-scale animal farming economically sustainable, embedding a fundamentally unethical practice deeper into society. Rather than perpetuating this cycle, we should invest in cruelty-free, sustainable alternatives.

We can thrive on nutritious, delicious plant-based diets at every life stage. With increasing innovations in alternative proteins, from plant-based meat substitutes to cultured meats, we must redirect technological advancements toward genuinely compassionate, environmentally-friendly solutions.

Towards a compassionate future

The rise of AI in farming highlights a critical juncture: technology can either perpetuate animal suffering or help us transition towards more humane and sustainable practices. By choosing more plant-forward diets and exploring sustainable alternatives, we can ensure innovation serves compassion, not cruelty.

Reducing meat consumption isn't just achievable, it’s enjoyable and rewarding.

Are potatoes really not ‘human food’? We checked the history and science

This fact check breaks down three main claims: claims 1 and 2 tackle the historical background behind potatoes’ popularity; claim 3 then examines in more detail the argument that consuming potatoes isn’t conducive to optimal health.

Claim 1: “The reason they had to eat those foods was because they were starving. That was all that was available.”

Fact-Check: The implication of this claim is that potatoes are ‘peasant food’, fit for survival, but not for optimal health. This implication is made clearer by one of theprimalbod’s comments on the video:

“If you want to eat food to survive go ahead. Climb the wall, be a peasant. I don't want [to] just survive, I want to dominate. I'll eat what the fucking kings and queens ate... the fucking meat!”

While potatoes have certainly been useful in hard times, they are not just desperation food. Let’s contextualise the whole story as recounted by Candi to see why it might in fact be just the opposite:

Potatoes were banned for a time… based on unfounded beliefs

In 1748, growing potatoes was banned by the French parliament, fearing they might spread leprosy. There was no scientific basis for this: leprosy is caused by bacteria, not potatoes, and is primarily spread through respiratory means (source, source). But medical understanding at the time was limited.

The Parmentier “guard trick” really happened… but tells only part of the story

A couple of decades later, Antoine-Augustin Parmentier, a French pharmacist and potato champion, did famously arrange for soldiers to guard potato fields during the day but not at night, essentially encouraging theft to make potatoes appear desirable. And it worked!

So yes, potatoes faced a bit of a PR challenge. But their success story is not a sign of dubious trickery. In fact it might be seen as an example of how societies overcome food myths to improve the health of the general population.

Potatoes at the heart of a new perspective on the links between food, health, and state wealth

In a paper published in the journal Eighteenth-Century Studies, food historian Professor Rebecca Earle urges for the contextualisation of accounts of potatoes’ history. She explains that one of the main reasons behind this push towards the adoption of the potato as a food staple was a realisation that nutritious food was conducive to good health; and that a large, healthful population was an asset to the state.

This goes completely against the implications of Candi’s claims: it suggests that people didn’t eat potatoes just because they had no choice. Rather potatoes were valued for keeping workers healthy and strong.

So, were potatoes just ‘poor people’s food’? Not really. People had been eating potatoes long before Parmentier’s stunts (he even gave potato bouquets to the French King and Queen). Rich households and armies ate potatoes, too. Indeed, reports from this time period allude to potatoes being consumed for pleasure by the wealthy (source).

They weren’t forced on people: they spread because they were cheap, filling, and a good source of nutrients.

More than just ‘survival food’

Potatoes are a rich source of carbohydrates, fibre (especially with the skin), potassium, and some B vitamins. Potatoes also contain small amounts of Vitamin C. In places like the UK where people tend to eat a lot of potatoes, they can be a good source of Vitamin C. Potatoes are also low in fat and highly satiating, making them a practical and nutritious part of many balanced diets.

Claim 2: A hybrid potato from Spain was bred to eliminate solanine, the “toxic poison that’s in potatoes.”

Fact-Check: This seems to be the point where Candi’s storytelling diverges from available historical accounts. Let’s start by explaining what solanine is, before moving onto the claim that it was bred out of potatoes before they became a popular food choice.

What is solanine?

Solanine is a type of glycoalkaloid (a naturally occurring chemical compound found in plants) most commonly associated with the nightshade family of plants. This includes potatoes as well as tomatoes, peppers and aubergine (source).

Plants produce glycoalkaloids like solanine as a natural defence mechanism against pests and diseases. But this doesn’t mean they’re unsafe to eat. In healthy, properly stored potatoes levels are generally low, especially in the tuber. However certain conditions can lead to increased solanine production. These include mechanical damage, light exposure, improper storage and sprouting. Other factors such as variety, genetic makeup, and growing or climate conditions can also affect solanine content (source). Such cases can often be detected by a green colour and bitter flavour (source).

Is solanine dangerous?

In large amounts solanine is indeed toxic to humans, however, poisoning is rare and usually only occurs after eating green, sprouted, or improperly stored potatoes. Additionally, ingested solanine is poorly absorbed and rapidly excreted by the human body (source).

Harriet Hall, MD, who was also known as The SkepDoc, wrote about this topic in Science-Based Medicine and brings a much-needed reality check:

‘It is estimated that it would take 2–5mg per kilogram of body weight to produce toxic symptoms. A large potato weighs about 300g and has a solanine content of less than 0.2mg/gm That works out to around 0.03mg per kilogram for an adult, a hundredth of the toxic dose; I figure a murderous wife would have to feed something like 67 large potatoes to her husband in a single meal to poison him’ (source).

For most people, the nutritional benefits of potatoes far outweigh the minimal risk. Only vulnerable groups like young children may be at risk with extreme exposure (source).

Were potatoes imported as hybrid potatoes?

Candi’s claim suggests that potatoes were brought over from Spain as hybrid potatoes, bred to have solanine removed, making them safer for consumption. To evaluate this claim, we need to consider the historical context and the state of breeding knowledge at the time.

While it’s likely that people recognised that green or bitter potatoes could cause illness, the chemical identity and biosynthesis of solanine were not understood until much later. Modern efforts to eliminate solanine (such as using CRISPR to knock out key genes like St16DOX) are 21st-century innovations that allow precise removal of solanine production pathways (source).

In the 18th century, people practiced selective cultivation, favouring tubers that were safer or tasted better, but without any understanding of solanine or plant genetics. Therefore, the suggestion that potatoes brought from Spain were deliberately “bred” to remove solanine is implausible. Rather, safer varieties likely became more common over time through informal selection.

Claim 3: “Carnivores can eat plants… we can eat them and not die [...] But it’s not our food. Our food is meat.”

Fact-Check: Candi’s argument is based on the assumption that humans are carnivores. She compares humans eating plants to obligate carnivores, like cats, eating plants.

This comparison is misleading as unlike obligate carnivores that depend on nutrients found in animal tissue and must eat meat to survive, humans are omnivores so are adapted to eat a varied diet of both plant and animal foods. This is reflected in the structure of our teeth, which includes molars for grinding, and our digestive system which is suited for both animal and plant foods (source). Evolutionary biology suggests that being omnivores gave humans a survival advantage by allowing dietary flexibility, supporting adaptation to diverse environments (source).

Moreover, there is no strong evidence that eating plants is bad for humans or that plants should be avoided. On the contrary most research suggests that diets rich in plant foods can have several health benefits.

Many studies have shown that an increased consumption of plants such as fruits, vegetables, nuts and whole grains is linked with lower risk of chronic diseases. One umbrella review found that higher fruit and vegetable intake was associated with reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, certain cancers and overall mortality (source).

It is true that meat can be a valuable part of a balanced diet. Lean, unprocessed meat, in particular, can be a good source of high-quality protein and essential nutrients like iron, zinc, and B12. However, diets based solely or predominantly on meat often lack fibre and essential nutrients, and are typically high in saturated fat.

It is also important to note that high consumption of red and processed meat has been consistently linked to an increased risk of several chronic diseases, including colorectal cancer, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (source) (source).

Overall Candi’s claim is imbalanced because it ignores the scientific consensus that humans are omnivores. Rather than dismissing plants altogether, we should instead aim for a balanced diet with a variety of nutrient-dense foods, from both plant and animal sources, to support long-term health.

Deep dive into: the power of storytelling

The video suggests that while plants can be eaten, their consumption doesn’t lead to optimal health. The argument is not supported by scientific evidence, but rather by a story. So what is it that makes storytelling so powerful, and why is it problematic when it comes to understanding nutrition?

One way social media has changed how we discuss nutrition is the popularisation of stories to explain nutrition questions.

Take a rather straightforward question: are potatoes a nutritious food? To answer this, or indeed any nutrition question, science rarely says just ‘yes’ or ‘no’. The scientific process involves asking more questions. The answer might be yes in one context, but not necessarily in another.

Stories are compelling, not just because they’re easy to listen to and to process, but because in a story, everything appears to be linked: there’s a reason for everything. This makes stories easier to accept. Once we’ve accepted a story, it then also becomes easier to dismiss contradictory information. That’s why fact-checking claims like this means not only looking at the science and history, but also unpacking the story that holds the above claims together.

So what’s the logic behind those claims?

The argument seems to rest on the idea that some foods are truly designed for humans, and others aren’t. The so-called ‘human foods’ are usually described as the ones our ancestors ate, or the foods people rely on in the wild, without any form of processing. In this reasoning, anything that has been modified in any way can be framed as bad: whether it is by causing disease, making you fat, or leaving you with non-optimal energy.

So, all of our society’s ailments can get pinned on ‘modern’ food. This idea feels relatable: people are tired, people struggle with weight loss, people try to eat ‘the right foods’ and still feel worse. This narrative gives a clear reason for those feelings of frustration: of course it doesn’t work, in fact it cannot work, because it wasn’t designed for us.

Think of the hunter-gatherer image people hold up in contrast: you might imagine a lean, active human chasing meat in the wild. No processed foods, no mystery ingredients… no diabetes? This picture is not necessarily accurate (source, source), but the claim and its logic are intuitive: stick to ancestral foods, and you’ll feel better.

And so the picture builds up. The story starts to make sense. Claims about the superiority of that way of life can get lots of attention on social media. In some of these narratives, certain foods, including ordinary crops like potatoes, can be cast as a ‘con’: marketed as healthy when they’re not.

But the story leaves a lot out

This narrative skips over some important facts and contains several flaws. As it gets repeated over time and gets accepted, it can end up distorting the picture of how nutrition actually works.

Firstly, restrictive diets, if not planned properly, can lead to nutritional deficiencies, and this is often not mentioned.

Secondly, not only do humans adapt to food, we also adapt food to us. The assumption that there’s a single ‘correct’ ancestral diet ignores the fact that what we eat has changed dramatically over time and continues to do so. And that is not a bad thing.

Farming, cooking, and breeding crops have also reshaped what we eat and how we digest food, allowing us not only to survive but to grow.

What does this tell us about human nutrition?

It tells us our diets and bodies are shaped by evolution. And that flexibility is not a flaw, it’s our species’ survival strength.

Final Take Away

What we have then is a tweaked tale to tell a compelling story. Yes there was a campaign to get working people to embrace potatoes, but not because that was “all that was available.” Yes potatoes were brought over from Spain, but not as a hybrid potato with solanine removed. Why do those details matter? Because the premise is that the story being sold explains why eating potatoes is not conducive to optimal health; why they’re not “our food” and were never meant to be.

That is not how evolution or nutrition work. Our diets evolve, our bodies evolve. Potatoes are very much our food: they’ve played a great role in supporting our growing population.

To imply from this story that humans should principally be eating meat and avoid plants is unsupported by evidence, and misleading. Consumption of plants is a vital part of a healthy and balanced diet. Given that current intakes of fruits and vegetables are already low, advice that we should avoid plants for optimal health can discourage people from adopting evidence-based strategies for better health and may risk promoting harmful dietary choices.

We have contacted Candi Frazier and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

We know more about nutrition today than at any point in history, but myths still spread fast. For advice you can trust, look for evidence-based sources: registered dietitians, reputable health organisations, or peer-reviewed science, not just viral stories.

In a recent video on social media, influencer Candi Frazier, known on Instagram as PrimalBod, suggests that potatoes are merely peasant food by telling a dramatic story: that potatoes were once banned, that rulers had to trick starving peasants into eating them, and that although we can eat them “and not die,” they aren’t truly our food.

This fact check breaks down those claims point by point, looking at both the history and the science behind them.

Full Claim: “Potatoes were banned in France, for a long time. They thought that potatoes gave everyone leprosy. Frederick the Great, the King of Prussia at the time, he was trying to get his people to eat potatoes because somebody from Spain had brought over this hybrid potato that they had bred out, the solanine, the toxic poison that's in potatoes. And he's like, try these. These can feed your people. And so he's trying to feed them to the people and the people weren't eating them. They're like, we're not eating those. The dogs won't even eat them. So what he did was he constructed this wall.

He started planting potatoes behind this wall and then he put guards out front because he wanted to trick the peasants into eating the potatoes and it worked. And at the time, he had prisoners of war. And one of the prisoners of war was a pharmacist and he worked with the French parliaments at the time.

And so when he became freed, he went back and started giving starving people in France potatoes and he showed that it could keep them alive. And so the parliament decided to release the law and now potatoes are everywhere, you know, French fries. The reason they had to eat those foods is because they were starving. That was all that was available. Carnivores can eat plants. We do it to our animals. Our cats and dogs that are carnivores, there's sweet potato, corn, green beans, alfalfa, oats in their dog food. And we feed it to them regularly and they don't die. So, yes, we can eat them and not die. But it's not our food. Our food is meat.”

The claim is based on real historical events: yes, potatoes were distrusted for a time, and yes, there were clever campaigns to boost their popularity. But the idea that this means potatoes “aren’t our food” ignores both the historical reasons behind those campaigns and how human nutrition works. Humans are omnivores whose diets have always evolved, and potatoes have long been part of that story.

Stories like this are compelling and dramatic. Plots involving bans and trickery are catchy and so get shared more easily, regardless of whether they are historically or scientifically accurate. If we don’t pause to check the evidence, we risk throwing out healthy, practical foods for no good reason.

Will reducing livestock really cause food shortages? Here's what the science says

Cultivating Common Ground

Farmers are not the problem — they’re vital partners in reaching net-zero. Good policy should support them financially and practically to diversify their farms, restore biodiversity, and produce more nutritious, sustainable food. Unfortunately, setbacks like the recent halt of the UK’s Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) make this transition harder for farmers and slow climate action.

Meanwhile, big agricultural corporations spend heavily on lobbying, pushing policies that favour industrial systems over small-scale farmers. This leaves local farmers vulnerable to climate threats and economic challenges. To succeed, small farmers need a seat at the table to shape smart, context-driven solutions.

Strong food policies should help farmers continue feeding their communities while moving towards sustainable sources of protein. This does not mean replacing animal products with ultra-processed foods. Thoughtful planning and structural changes are needed to succeed in shifting toward plant-rich diets. It will take significant efforts to make nutritious foods accessible for everyone. Investments in plant-based protein, agritech, and more efficient practices can help do that while boosting farmers’ incomes and positioning them as leaders in the shift to net-zero.

Diet is personal and cultural, which makes these conversations sensitive. But despite polarised debates, common ground exists: environmentalists, farmers, and consumers all want healthy food, thriving farms, and a livable climate. By reducing animal product consumption — not eliminating it — we can protect food security, biodiversity, and farmers’ livelihoods together.

So, will reducing livestock cause food shortages? The science says no, and done wisely, it might help prevent them.

We have contacted Gareth Wyn Jones and are awaiting a response.

Claim 2: Livestock are not contributing to climate change.

Fact-check: Jones passionately argues that cows are not the problem, dismissing livestock's climate impact. However, this position doesn’t align with the scientific consensus.

Plant-rich diets could drastically reduce food-related emissions

Globally, livestock production emits 7.1 gigatons of CO₂ per year, which accounts for about 14.5% of human-induced greenhouse gas emissions. If that seems like a lot, it is.

For a comprehensive view of food related environmental impacts, a 2018 meta-analysis discussed what would happen if we stopped animal-sourced food production and consumption. This hypothetical scenario showed the potential to reduce agricultural land use by 76%, creating the opportunity to sequester 8 gigatons of CO₂ on pastureland and croplands that would have been used for animal agriculture.

The data shows great potential in shifting plant-based: the huge amount of CO₂ from livestock emissions could be avoided, and an additional huge amount of CO₂ could be sequestered in vegetation and soils through rewilding.

Having the entire world go plant-based is an extreme example, but large reductions in land use would be possible even without a global plant-based diet. A focus on cutting out beef and dairy would lead to big reductions in agricultural emissions.

This is the case because cattle emit substantial methane—a potent greenhouse gas roughly 28 times stronger than carbon dioxide over a 100-year period. Producing just 1 kg of beef protein releases roughly 300 kg of greenhouse gases—a remarkably inefficient and climate-costly exchange (source). Furthermore, livestock-driven land-use change, including deforestation, significantly exacerbates climate impacts. Approximately 80% of deforestation globally is directly linked to agriculture, especially the expansion of pastures for cattle grazing.

Decisions around land use and diet change are context dependent.

What we eat directly impacts how land is used, so it’s important to consider trade-offs between livestock production methods when making diet decisions. Industrial livestock systems often raise ethical concerns around animal welfare, but are more efficient due to faster animal growth, higher yields, and concentrated feeding (source). Regenerative, pasture-based systems like Jones’ provide better animal welfare and may support soil health, but require significantly more land and often emit more greenhouse gases since animals take longer to mature.

It’s all about context—shifting toward plant-based diets can help reduce emissions in high-income countries where meat consumption is excessive and alternatives are readily available. However, this approach is not always feasible in low-income regions where animal-based foods are critical for nutrition and livelihoods—largely due to impacts of colonialism that perpetuate an unjust global food distribution system. Land use should also be context-driven, factoring in both carbon storage potential and food production needs. In regions where pastureland yields low livestock productivity, rewilding is an efficient alternative for carbon sequestration (source).

And while its advocates argue regenerative grazing can mitigate livestock emissions, research shows its potential is limited and supporting evidence is scarce. At best, it's complementary—not a complete solution. Regenerative grazing systems alone, without a reduction in animal-sourced foods that free up land, are insufficient to tackle climate goals fully.

The narrative around food shortages linked to net-zero targets is common but can easily be misguided without more context. Here's why reducing livestock is both necessary for climate action and compatible with achieving global food security.

Claim 1: Reducing livestock numbers will cause food shortages and harm human health.

Fact-check: Jones argues that reducing livestock to meet net-zero climate goals will lead to widespread food shortages and poorer health. But what does the data say about these issues?

Plant-rich diets are less resource intensive

On the surface, it seems logical: fewer animals might mean less food, right? But reality is far more nuanced. Livestock farming is resource-intensive, requiring large amounts of land, water, and feed. Currently, less than half of global cereal production directly feeds people, with 41% used solely as animal feed. In the UK, approximately 50% of cereals are fed to livestock, while in the U.S. the disparity is even more pronounced—with only about 10% of cereals directly consumed by humans. Studies repeatedly demonstrate that reallocating even modest amounts of land used for livestock production to crop production directly for humans can feed significantly more people.

For instance, producing plant-based foods like grains, legumes, and vegetables requires substantially less land—approximately 10 to 20 times less per calorie—compared to beef and dairy products. In practical terms, the same amount of farmland can feed significantly more people if dedicated to plant-rich diets than animal-based ones.

The greatest threat to food security may be climate change itself

Staple crops such as wheat, maize, and rice are increasingly vulnerable to climate impacts. Extreme weather events, intensified by climate change, continue to threaten yields worldwide, with projections suggesting a 50% likelihood of a global food disruption event within the next three decades. Not to mention that higher CO₂ levels also reduce nutritional quality in staple grains, exacerbating malnutrition risks globally.

And although voices on social media may say otherwise, transitioning to plant-rich diets does not mean completely abandoning animal agriculture. The emphasis is on reducing excessive dependence on livestock to free up resources for diversified food production and ecosystem restoration.

Lastly, the argument that less meat would mean less healthy populations isn’t supported by scientific evidence. The EAT-Lancet Commission and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) both highlight that balanced diets featuring more plant-based foods contribute significantly to reducing chronic diseases, including heart disease, diabetes, and obesity, thus enhancing public health overall.

The calories that are lost by feeding crops to animals, instead of using them directly as human food, could theoretically feed an extra 3.5 to 4 billion people (Ray et al., 2022; Cassidy et al., 2013). The focus indeed should be on rich privileged countries shifting more plant based, but even less resourced countries, like some in Africa, are not benefiting from KFC and other major meat chains expanding there. This often comes at the detriment of culturally relevant traditional plant based foods.

Grazing animals use 37% of Earth’s ice-free land but provide only 5% of global protein (IPCC), while beef emits 20x more GHGs and uses 20x more land per gram of protein than plant sources like beans (Ranganathan et al., 2016). Even if regenerative grazing worked perfectly, it would take 61–225 years to offset livestock emissions (Wang et al., 2023). Instead, shifting plant-based and rewilding that land could remove 8 Gt CO₂ per year and feed billions more (Poore & Nemecek, 2018; Hayek et al., 2021).

The solution is clear. But industry myths and pastoral cultural holds prevent positive shifts.

For accurate information on sustainability issues, rely on evidence-based sources that considerthe full environmental impact, including emissions, resource use, and biodiversity.

In recent remarks across his social media platforms, Gareth Wyn Jones, a Welsh hill farmer, argues that global efforts to achieve net-zero by reducing livestock numbers will lead to widespread food shortages and an unhealthy population. While his concerns deserve consideration, the conversation around food security and climate action presents a different view.

Claim 1: “This is not just a problem in the UK, it’s a global problem, every country is pushing down the livestock numbers to create a so-called net zero…we might get to net zero, but I’ll tell you something, there’ll be a lot of hungry people and there’ll be a lot of people that are going to be a lot poorer because of the food they’re eating…”

Claim 2: “These creatures are part of the solution, not the problem, these aren’t causing any climate catastrophe…”

Despite fears that cutting livestock numbers could trigger global hunger, research consistently shows that shifting towards plant-rich diets and reducing livestock production is not only critical for climate stability but will not inherently cause food shortages. On the contrary, such changes could significantly improve global food security, human health, and sustainability.

Understanding the real impact of livestock farming on food supply and climate change is essential. Misinformation that downplays livestock’s environmental impacts and fear mongers about food shortages can hinder meaningful progress towards net-zero. To tackle climate change effectively, we need accurate discussions about the impacts of our dietary habits and agricultural systems. This isn't about eliminating animal products entirely, but rather making meaningful shifts toward diets richer in plants to protect our planet and ensure abundant, nutritious food for everyone, not reduce availability.

Can the UK's new food strategy fix our broken relationship with food?

Correction & Clarification (27th July 2025]) A previous version of this article incorrectly claimed the UK Food Strategy mandated policy changes regarding plant-based agriculture and local sourcing requirements for public institutions. These claims were incorrect, the UK Food Strategy outlines a vision without introducing new mandates. We apologize for this error, have corrected the text accordingly, and are committed to improving our editorial processes to prevent similar inaccuracies in the future.

---

Food isn’t just fuel, it’s central to our health, environment, and communities. Yet, the UK’s relationship with food has become increasingly complex and problematic. Rising obesity, environmental damage, and growing food insecurity highlight deep-seated issues. In response, the UK government released its Food Strategy on July 15, 2025, after engaging over 400 stakeholders, from farmers and businesses to researchers and citizen groups. But can this strategy genuinely reshape the system?

Understanding the UK's food challenges

Health concerns

Obesity has become a national priority. Currently, 64% of adults in England are overweight or obese, double the rate since the 1990s. Obesity-related illnesses cost the NHS more than £11 billion each year. Additionally, children from deprived backgrounds are disproportionately affected, deepening health inequalities.

Environmental impacts

Food production covers nearly 70% of UK land, and intensive farming methods have contributed significantly to pollution, biodiversity loss, and greenhouse gas emissions. Pollution from industrialised animal agriculture and aquaculture now affects about half of the UK’s inland waters, raising concerns about long-term sustainability.

Food security sssues

Food prices surged by 36% recently, driven by global events like the conflict in Ukraine. Over 4% of the UK population now relies on food banks, underscoring increasing vulnerability. Low domestic production of fresh fruits and vegetables further exposes vulnerabilities in the UK food supply.

What the food strategy actually proposes

The newly released UK Food Strategy outlines a long-term vision built around ten priority outcomes, including healthier diets, reduced food waste, and support for sustainable agriculture. However, it's crucial to emphasize that this document primarily establishes strategic direction and does not introduce new mandatory policies or legislative changes.

Healthier eating goals

The strategy reaffirms existing commitments to healthier eating, including clearer food labelling, ongoing work to reduce unhealthy food advertising aimed at children, and reformulation targets for salt, sugar, and fat. These reflect ongoing government initiatives rather than new mandates.

Sustainability and agriculture

The strategy aligns with ongoing environmental programs such as the Land Use Framework and Environmental Land Management Schemes (ELMS), aimed at supporting more sustainable agricultural practices. However, despite advocacy for a stronger emphasis on plant-based agriculture from groups such as Plant Based Treaty, the government strategy itself does not mandate a shift to plant-based farming.

Public procurement

Advocacy groups have strongly encouraged policies requiring public institutions like schools and hospitals to source at least half of their food sustainably or locally. While such ideas have been discussed in public consultations and political circles, the Food Strategy itself does not currently mandate these targets.

Expert and stakeholder reactions to broader food policy issues

The UK's Food Strategy has sparked discussions within the food policy community, although it's important to note that some stakeholder reactions reference broader debates and previously established policy areas rather than direct responses to this particular strategy.

Supportive Comments:

- Simon Roberts, CEO of Sainsbury’s, has previously supported the principles outlined in similar government initiatives, emphasizing nutrition transparency and infrastructure investments crucial for resilient food systems.

- The Institute of Food Science and Technology (IFST) consistently advocates for inclusive and evidence-based approaches within food policy discussions, highlighting equitable access to nutritious foods.

Critical Concerns (Predating or Parallel to the Strategy):

- The House of Lords Food, Diet & Obesity Committee previously described the overall UK food system as "broken," recommending stricter regulations, including taxes on unhealthy ingredients, to address systemic issues.

- Zoe Williams (The Guardian) has highlighted ongoing affordability challenges, underscoring the persistent price gap that makes healthier foods less accessible for lower-income households.

- The Food Foundation has consistently reported that healthier food options remain significantly more expensive than processed foods, advocating policy changes such as removing VAT from healthy products.

- The Environment Committee Chair expressed concern about farmland reduction policies and the absence of a comprehensive rural strategy, emphasizing potential risks to domestic food production capabilities.

These insights provide valuable context to the ongoing conversation surrounding food policy, acknowledging that many critiques and supportive statements were established prior to the release of this specific strategy or are addressing intersecting food system issues more broadly.

Our role as consumers in shaping the food system

While governmental strategy sets the overall direction, meaningful change depends on collective action:

- Support local and sustainably produced food to boost local economies and reduce environmental impact.

- Choose plant-forward meals occasionally to improve health and reduce ecological strain.

- Engage in policy conversations through consultations and community initiatives.

Moving forward transparently

The UK's Food Strategy offers a vision rather than a detailed policy roadmap. Real transformation will rely on subsequent clear policy commitments, adequate funding, and transparent communication from the government, as well as active participation from citizens, businesses, and community leaders.

By openly recognizing both the strengths and limitations of this strategy, we can move forward thoughtfully, collectively reshaping our relationship with food for the better.

Why the raw meat craze is dangerous. And why influencers won’t say it

Eddie Abbew begins his video by arguing that, from a logical standpoint, the only foods humans can safely consume without excessive cooking are meat and fruit. He then takes a bite of raw meat and confidently states, “there’s nothing wrong with eating raw meat.” On the surface, this might seem like a personal dietary choice. But framed as a demonstration of safety, and broadcast to a wide social media audience, this claim is misleading and potentially dangerous.

The evidence on the risks associated with consuming raw meat is extensive, and most people are probably familiar with those risks. So before reviewing this evidence in detail, let’s take a close look at the underlying assumptions that tie this argument together.

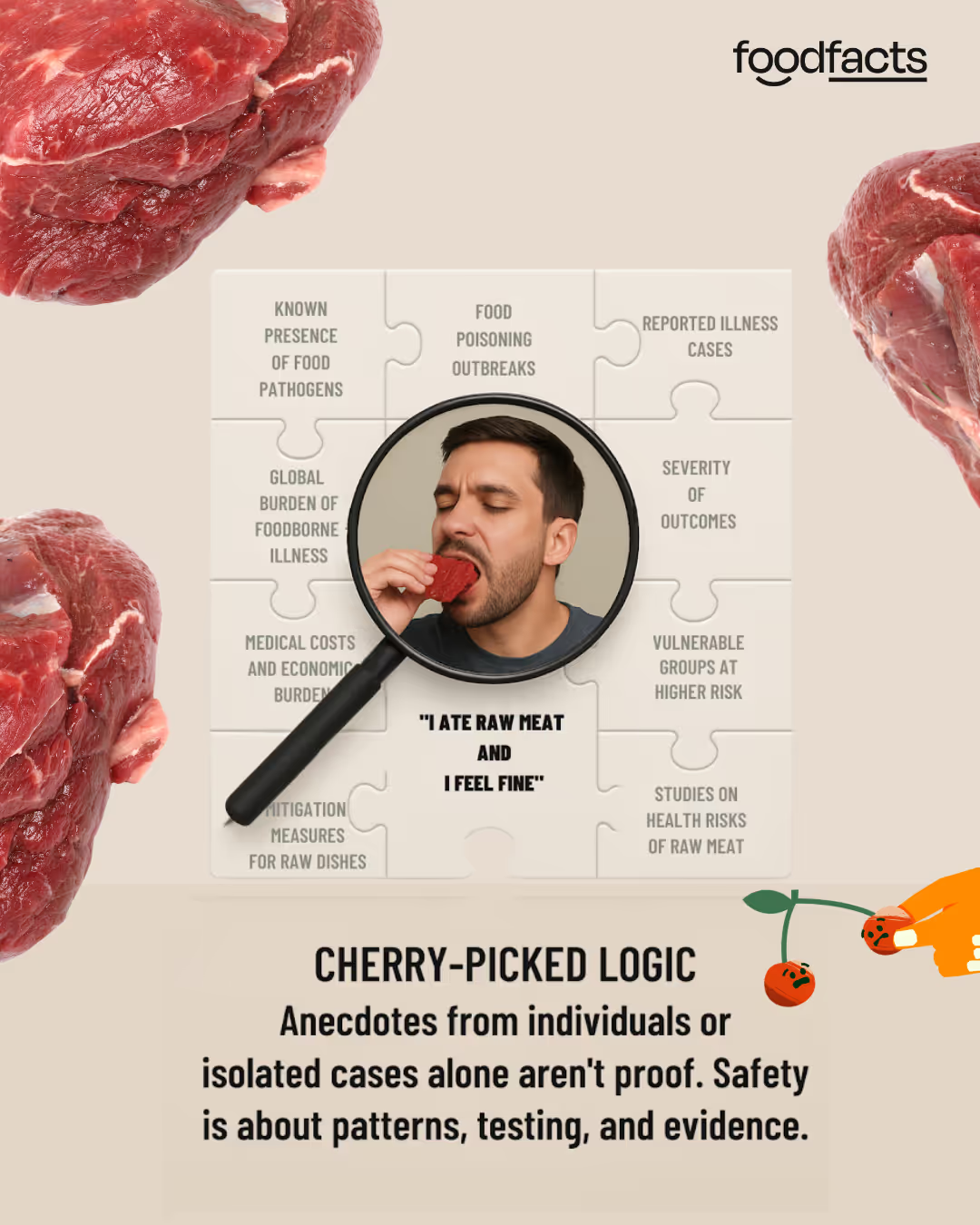

In this video, raw meat appears to be the epitome of what Eddie Abbew calls “real” food, food that he claims is designed for human consumption, in contrast with any form of processed products, which he regularly criticises. Within this perspective, the polar opposite would probably be ultra-processed, plant-based meat. Interestingly, in a later video posted just a few days later, Eddie Abbew warns his audience about the dangers of Quorn products, citing the tragic story of a young boy who died after suffering from a severe allergic reaction — which is an immune response, not the same as an infection caused by bacteria in food. The implication is clear: natural, unprocessed food like raw meat is safe; foods made in a factory are not.

But this logic doesn’t hold. If it did, then bringing up the case of one person having died after consuming raw meat would be enough to argue that equally, raw meat isn’t safe. However, from a scientific, logical perspective, this would not be enough: how a single person reacts to a food, whether negatively or not at all, is ONE single piece of a much larger jigsaw puzzle. It matters, but on its own, it cannot tell us whether that food is safe for the broader population.

What can? Scientific evidence looking at patterns, testing, and data.

Decades of research show that raw meat is a common source of pathogens like Salmonella, E. coli, and Listeria, all of which are killed during cooking. These bacteria are responsible for many cases of foodborne illness each year, some of which lead to hospitalisation or death.

This doesn’t mean eating raw meat always causes illness, just as not wearing a seatbelt doesn’t always lead to injury. But the risk is there, and it should not be ignored. Following that logic, we should also come to the conclusion that wearing a seatbelt is not necessary, which would be considered dangerous advice. In both cases, the risks are real and well-documented, and so is the effectiveness of solutions. Cooking is one of the simplest and most effective tools we have to eliminate the risks of developing foodborne illnesses when we eat meat.

❌ Claim: “There’s nothing wrong with eating raw meat.”

Fact-Check: ✅ Raw meat consumption carries well-established health risks, including exposure to Salmonella, E. coli, Listeria monocytogenes, and parasites like Taenia saginata (source, source). These pathogens can lead to severe illness, hospitalisation, or even death, especially in vulnerable groups like children, pregnant women, the elderly, and people with a weakened immune system (source). This information is left out from Eddie Abbew’s video in which he states that meat is one of the only foods humans can safely eat without excessive cooking.

Reports from multiple countries, including the U.S., Ethiopia, Lebanon, and Japan, consistently link raw meat consumption with foodborne illness and support strict safety guidelines and enhanced public education (source, source). For example, a Salmonella outbreak which occurred in Wisconsin in 1994 was traced back to the consumption of raw ground beef. Some patients reported that eating raw ground beef over the winter holidays was a practice brought from their European ancestors (source), highlighting the importance of continuing to raise awareness of raw meat risks, especially when linked to cultural practices.

Indeed foodborne illnesses impose a significant burden (source, source), estimated to cause over 400,000 deaths each year worldwide, 30% of which occurring among children under 5. However, research shows that food safety education, from proper cooking to avoiding cross-contamination, can greatly reduce those risks. This guide offers clear information on this topic.

✅ Improper cooking is directly linked to outbreaks and hospitalisations

Historical outbreak investigations have shown undercooked meat to be a leading cause of foodborne illness. For instance, E. coli outbreaks have led to numerous hospitalisations and can have serious complications especially among vulnerable populations. These are most often linked to undercooked raw meat, especially beef (source).

What about steak tartare?

Many cultures around the world serve traditional dishes made with raw or lightly cured meat: from steak tartare in France, to carpaccio in Italy, to dishes like kibbeh nayyeh in the Middle East, and raw liver or sashimi-style preparations in parts of Asia. Because these foods are part of established culinary traditions, it’s understandable to wonder: If restaurants serve them, surely they must be safe?

However, while these dishes are often prepared with special care, strict hygiene, and high-quality cuts chosen specifically for raw consumption, eating raw meat still carries real risks, including exposure to harmful bacteria and parasites. That is why food safety guidelines typically recommend consuming them only from reputable sources that follow rigorous handling and preparation standards, and generally advise against them, even in countries where raw meat dishes are more popular.

A review of the evidence conducted by Public Health Ontario in 2018 concluded that “[f]or meat intended to be consumed raw, production practices as well as preparation methods may reduce but not eliminate the risk of disease. Warnings about the risks associated with raw meat consumption can help inform decision-making by consumers” (source).

Final Take Away

At the end of the day, food choices are personal. Eddie Abbew is free to eat raw meat, seek out information on how to minimise the risks for himself, and share his opinions on the subject. But when suggesting to a wide audience that consuming raw meat is safe, the message becomes more than just a personal choice: it exposes viewers to serious public health risks.

Most people generally know that eating raw meat carries risks. But when a trusted wellness influencer eats it on camera with no immediate consequences, it can create doubt about the accuracy of food safety guidelines. It’s important to remember that illness isn’t inevitable. However, isolated videos showing someone eating raw meat without getting sick can distort risk perception and downplay the bigger picture: just in the UK, millions of people suffer foodborne illnesses every year; that’s thousands every single day (source).

It’s not just about saying “raw meat is okay”, it’s about encouraging distrust in food safety guidelines built on decades of research and real-world outbreaks. It’s about undermining trust in health authorities whose job it is to keep the public safe.

We have contacted Eddie Abbew and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Be skeptical of sensational content: while it attracts views and engagement, evidence should support health-related claims.

On June 10th, influencer Eddie Abbew posted a video on Instagram, in which he claims that “there is nothing wrong with eating raw meat.” He suggests it is designed for human consumption in its raw state. Below, we fact-check these claims against the scientific evidence on raw meat consumption and the health effects of cooking meat.

Full Claim: “If you think about it logically, the only things that human beings can eat without having to cook the **** out of is meat, and fruit [...] but there’s nothing wrong with eating raw meat. There are so many cultures that actually eat raw meat. A bit of salt, there’s nothing wrong with it.”

Eating raw meat carries well-established health risks from harmful bacteria and parasites that cooking can eliminate. Some populations are particularly vulnerable to those risks, including young children, the elderly, pregnant women and those with a weakened immune system. Foodborne illnesses represent a significant health burden and can easily be avoided by following food safety practices.

Bold claims and shocking videos tend to do well on social media because they drive engagement. By eliciting emotional reactions, they also attract more comments - positive or negative. This also means they are more likely to reach wider audiences. When following the shared advice can lead to serious health complications, it needs to be challenged.

Latest fact-checks, guides & opinion pieces

.svg)