Perfectly imperfect: why choosing 'wonky' veg matters more than ever

Rejecting the Myth of Perfect Produce

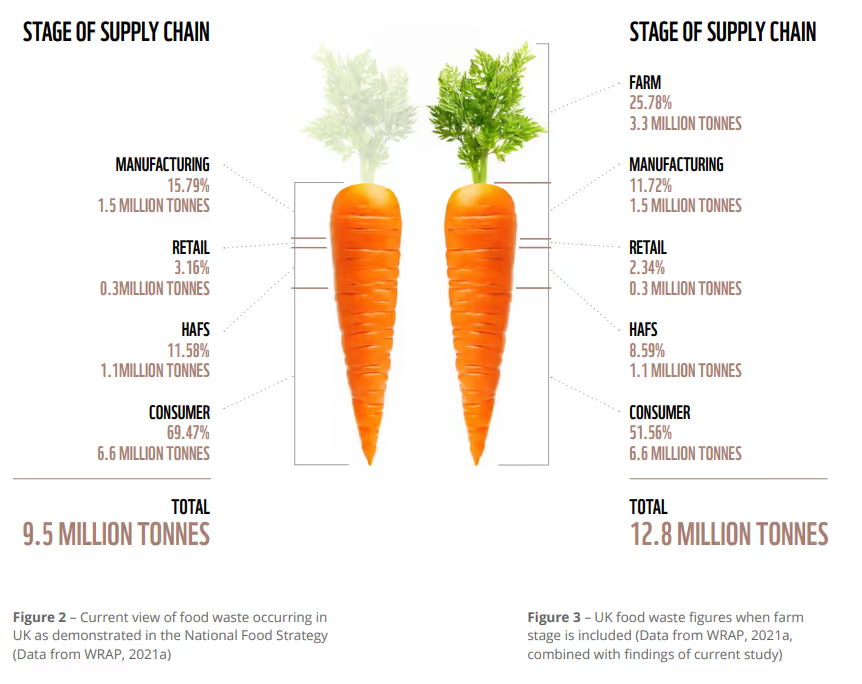

Every year, millions of tonnes of nutritious, flavourful produce never reach supermarket shelves. Around 3 million tonnes of edible food is wasted on UK farms each year! Their crime? Being too misshapen, too big, or too small. Strict supermarket cosmetic standards, driven by outdated perceptions of perfection, directly contribute to massive food waste at the farm level. But is it time we questioned these assumptions and embraced the wonky wonders of our food system?

The Real Cost of Cosmetic Standards

Oddbox, a company dedicated to rescuing surplus produce, identifies supermarket cosmetic criteria as a primary culprit behind farm-level food waste. Produce is often rejected not for taste or quality but simply for disrupting uniformity on supermarket shelves. This rejection creates a hidden crisis: wasted effort, wasted resources, and untold environmental damage.

The ‘Perfect’ Produce Myth

Consumers tend to imagine fruit and vegetables as perfectly formed, free of bruises and variations to shape and size and colour. Produce that did vary from the norm (or more fairly, was normal, but not what consumers felt was normal) was seen as undesirable and potentially unhealthy or dangerous. Fruits and vegetables that took this form have been unfairly seen as second-rate. However, these outdated associations are shifting as consumers begin prioritizing flavour and freshness over appearance, challenging entrenched narratives around food quality. The shift also reveals an underlying reality: taste and quality often reside beneath an imperfect exterior.

Consumer Expectations: Changing the Game

The belief that consumers only desire uniform produce has long driven retailers’ policies. However the team at the Oddbox notes an encouraging shift: consumers increasingly appreciate that taste and freshness matter far more than appearances. Awareness campaigns help consumers proudly embrace oddly shaped apples and carrots, recognizing beauty in imperfection. Education plays a crucial role here, people empowered with knowledge willingly adjust their preferences, thereby reshaping market demands and supermarket practices.

Food Waste: An Environmental Emergency

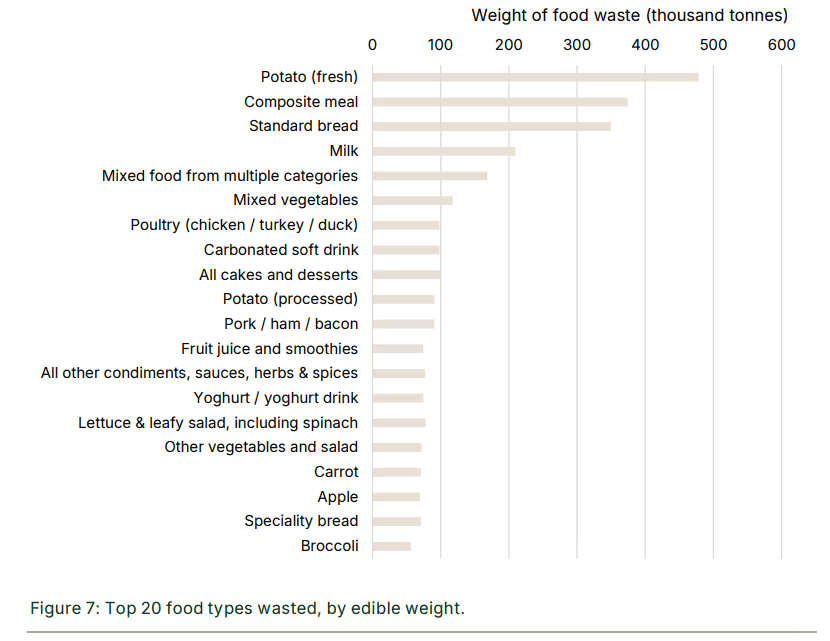

Food waste statistics in the UK paint a grim picture. British households waste approximately 4.5 million tonnes of edible food annually, with potatoes topping the list at nearly half a million tonnes. Bread and milk closely follow. This waste is more than just lost food, it represents squandered resources, including vast amounts of water, energy, and land. Critically, food waste contributes significantly to global greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for approximately 8-10% worldwide, five times the emissions from the aviation sector. When food decomposes in landfills, it produces methane, a greenhouse gas 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Understanding the Climate Connection

Food waste isn’t just an ethical concern; it’s a critical climate issue. Every kilogram of wasted food has embedded within it countless litres of water, significant energy expenditure, and hectares of land use. Reducing waste directly decreases the strain on natural resources and lowers emissions. It’s a tangible, powerful way for individuals to participate actively in climate action.

"We can't just think about food waste in terms of the methane emissions that are released when it breaks down. All of the energy, fertilizer, pesticide, water, land, and other resources that go into producing food that ends up in the bin is also wasted. Not only does this harm the planet, it reduces the value of food, costing both farmers and households money. Reducing food waste is an important step that we can all take to reduce our impact on the planet."

Matthew Unerman (Sustainability Campaigner at foodfacts.org, co-author of WWF's Hidden Waste report)

Busting Myths about Imperfect Produce

Misconceptions persist that imperfect produce is inferior in taste, nutrition, or shelf life. However, companies like Oddbox emphasize that these beliefs are wrong. Many factors causing surplus, such as overproduction or last-minute retailer cancellations, are unrelated to the produce's quality. Indeed, imperfect produce often offers superior taste, as flavour isn’t dictated by appearance but by freshness and ripeness.

Shifting Attitudes: Practical Steps for Change

Practical consumer advice includes selecting loose produce over packaged options, creatively using leftovers, and consciously avoiding overbuying. Shopping mindfully reduces waste and encourages supermarkets to reconsider their stocking strategies. Embracing oddly shaped vegetables and fruits enriches meals, inspires culinary creativity, and nurtures a culture that values resourcefulness and sustainability.

The Power of Collective Action

The team at Oddbox quantifies its impact with compelling evidence: since its inception, their community has saved over 51,000 tonnes of produce, with ambitions to reach 150,000 tonnes by 2030. This achievement highlights the significant potential for collective action. Small, regular choices accumulate, delivering substantial environmental benefits and influencing broader societal change.

Reimagining Our Relationship with Food

At its core, embracing imperfect produce invites us to rethink our broader relationship with food. It challenges us to confront our biases and recognize the invisible connections between food choices and global environmental health. Choosing 'wonky' produce isn’t simply about environmental responsibility; it’s about redefining our values and priorities.

Embracing Imperfection for a Better Future

Choosing 'wonky' produce goes beyond reducing waste. It's a declaration of consumer values, prioritizing flavour, freshness, and sustainability above superficial perfection. Embracing imperfection empowers consumers, enriches communities, and actively reshapes our food culture, creating a future where sustainability isn't just possible but celebrated.

If you want to save food waste with Oddbox visit them on their website, use the code FOODFACTS to get 25% off your first four weeks.

What does 'free range' really mean? The facts behind the label

When you see 'free range' on a carton of eggs or a package of chicken, it’s easy to picture animals roaming outdoors, enjoying the sunshine and fresh air. For many, 'free range' is shorthand for humane, natural, and ethical farming. But does the label live up to the image?

In this article, we explore what 'free range' really means, how it’s regulated, and what conditions animals actually experience in these systems.

What Is the Legal Definition of 'Free Range'?

The definition of 'free range' varies by country, species, and certifying body—and in some cases, it’s barely defined at all.

- In the U.S., the USDA requires that poultry labeled 'free-range' have “continuous access to the outdoors during their production cycle,” but it does not specify how much space, for how long, or the quality of that outdoor area.

- In the U.K., 'free-range' chickens farmed for meat are required to have access to outdoor space for at least half of their lives, whereas hens farmed for eggs must have continuous daytime access to runs which are mainly covered with vegetation and a maximum stocking density of 2,500 birds per hectare. But again, the specifics vary, and enforcement is inconsistent.

- For other animals, such as pigs and cows, free range has no legally binding definition unless certified by a third-party program such as Red Tractor or RSPCA Assured.

This means that free range can range from meaningful access to open pasture… to a small, barren yard that animals rarely use.

Do ‘Free-Range’ Animals Really Go Outside?

Not necessarily. “Access to the outdoors” can mean a tiny pop-hole in a crowded barn that leads to a small patch of dirt. Whether animals use that access depends on the following:

- Location of exits: Pop-holes may be far from where animals rest or feed.

- Size and design of outdoor space: If it’s cramped, muddy, or uninviting, animals may avoid it.

- Stocking density: In densely packed barns, competition or fear may deter animals from using exits.

Are Indoor Conditions Better in Free Range Systems?

In most cases, the indoor environment remains similar to conventional systems—large sheds housing thousands of birds or animals. Key concerns include:

- High stocking density: Even in 'free-range' barns, animals often have just a square foot or two of space per bird.

- Limited enrichment: Natural behaviors like foraging, dust bathing, or social interaction are often restricted.

- Short lifespans: In the poultry industry, birds may be slaughtered at just 5–8 weeks of age, meaning their outdoor access (if any) is limited and short-lived.

So while the label suggests freedom, the lived experience of many 'free-range' animals is still one of confinement, stress, and premature death.

Why Do People Believe Free Range Is More Humane?

Marketing and imagery play a major role. Labels featuring green fields, blue skies, or phrases like “farm fresh” or “raised naturally” create strong associations—even if those conditions aren’t legally required or practically delivered.

Consumers understandably want to make compassionate choices. However, research shows that public understanding of labels like 'free-range' is often inaccurate. In one UK survey, over 70% of consumers believed ‘free-range’ hens lived most of their lives outdoors, when in fact the majority spend most of their time indoors.

“Unfortunately, ‘free range’ means very little in terms of animal welfare and is often employed as a marketing ploy. Many free-range hens, for example, spend most of their lives in vast, stinking, overcrowded sheds. Due to the national avian influenza (bird flu) outbreak, eggs from hens kept indoors under a compulsory housing order can still be labelled ‘free range’ even if the birds have never been outside. Eggs aren’t essential for a healthy diet and are linked to heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and food poisoning. Ditching them is best for the animals and could benefit your health and the environment.” - Dr Justine Butler, Head of Research at vegan campaigning charity Viva!

Is Free Range Better Than Conventional Farming?

In some cases, yes. ‘Free-range’ systems may offer marginally more space, some natural light, or reduced antibiotic use. But these improvements are often modest and inconsistent.

The gap between consumer perception and actual conditions is wide—and it’s this gap that industry marketing is designed to maintain. While free range sounds like a kinder option, it's not a guarantee of good welfare, and it is not anywhere near natural living.

Reclaiming Transparency in the Food System

Free range should not be a feel-good label that obscures reality. It should mean what it implies: that animals can live a part of their lives outdoors. Until labeling standards catch up with consumer expectations, it’s up to all of us to ask more questions, demand better definitions, and support transitions toward food systems that align with transparency, empathy, and sustainability. If you’re not sure about the conditions that the animals were raised in, the best choice you can make is to skip purchasing those eggs, meat, or dairy products. Skipping out on some animal products won’t make your life any worse, but buying these products is more likely than not to cause suffering to animals.

Can feed additives really fix the methane problem?

Big industries follow one rule: protect profit. The trillion-dollar animal agriculture sector is no exception. After years of criticism for its impact on the planet, animals, and food systems, meat and dairy giants are now trying to clean up their image. But the real question isn’t if they’ll change, but how, and whether those changes will make a real difference. Enter a series of promising-sounding feed additives. But do they deliver? Let’s take a closer look.

Let’s Talk About Methane

For the first time, 2024 was the first year above the critical 1.5°C global warming threshold, and this March shattered temperature records worldwide. We’re in a climate crisis, and transformative changes are urgently needed, especially from the agricultural sector.

Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas with a warming effect that is 86 times stronger than carbon dioxide, and livestock accounts for 32 percent of human-caused methane emissions. These emissions come from cattle, and their burps in particular, due to the microbes in cattle's digestive systems, which help them break down fibrous plants like grass that humans can’t digest. With around 1.5 billion cattle on the planet, their methane adds up pretty quickly. Yet instead of reducing herd sizes or rethinking the industrial farming model, the industry is focusing on feed additives as quick fixes.

Red seaweed as a feed additive

One of the most recent hyped feed additives is a type of red kelp (Asparagopsis taxiformis), claimed to reduce methane by up to 99%. But in a major real-world trial - conducted by Meat and Livestock Australia (MLA)- results dropped to just 28%, and that’s before factoring in the downsides: cows ate less, produced less milk, and were 15 kilograms underweight at slaughter. Needing an extra 35 days to ‘catch up,’ the methane reduction dropped closer to 19%. Even worse, the active compound in seaweed, bromoform, has been linked to inflammation and toxicity in animals.

Bovaer: Frankenstein's Milk

Feed additive Bovaer, developed by DSM-Firmenich, is a synthethic organic compound that has been authorized for use in over 65 countries. The active ingredient in Bovaer is 3-nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP), which works by inhibiting an enzyme in the cow’s stomach that helps produce methane during digestion. On average, it is said to reduce methane emissions by 30% in dairy cows, and 45% in beefcattle.

However, Bovaer has gained attention for other reasons. Public mistrust has led to the nickname "Frankenstein's Milk," with consumers, farmers, and influencers criticizing the product. This nickname reflects concerns about unnatural interventions in food production, fear of chemical manipulation, and skepticism of large corporations.

Although Bovaer has passed multiple trials and been approved by various regulatory authorities, questions about its genotoxicity (the potential to cause genetic damage) were not fully clarified. This means its long-term genetic safety is still uncertain. Additionally, it has not been definitively proven that Bovaer is safe for other animal species, or that it poses no risks to those who handle it.

Nitrates as a feed additive

Nitrates, chemical compounds made of nitrogen and oxygen, are also added to cattle feed to reduce methane emissions. It is said to lower methane emissions by up to 14%, yet research shows that it might also lead to increased emissions of nitric oxide (NO). As a result, there are diminishing returns in emission reduction for this feed additive due to the higher NO emissions released by higher levels of nitrates.

The biggest concern is that when nitrates are broken down in the rumen, they first convert to nitrites before becoming ammonia. If the process is too fast or the dose too high, nitrite can build up in the animal’s blood, potentially leading to nitrite toxicity, which can cause serious health problems like methemoglobinemia - a potentially fatal condition where blood loses its ability to carry oxygen.

So, do feed additives deliver on their promises?

The list doesn’t stop there. There’s a wide range of other additives like tannins, fats, oils and saponins that are used. It is true that the mentioned additives show potential to reduce methane emissions, but many come with trade-offs and long-term effects on animals and ecosystems are still not clear. Meanwhile, they do nothing to address the scale of animal production, which continues to rise globally. And they can’t touch the massive emissions and ecological damage tied to feed crops, deforestation, manure, or slaughter. Trying to green a fundamentally unsustainable system won’t get us where we need to go.

These efforts represent only a small part of a much larger strategy. The animal agriculture industry has funded research to produce favorable emissions reports, downplayed the importance of individual action, shaped public conversations about dietary changes, and even created a front group, the Food Facts Coalition, to defend the industry against criticism of livestock farming.

If we’re serious about tackling climate breakdown, we need to look beyond quick fixes and rethink the system itself. Studies show again and again that a plant-based diet is our best and most immediate chance to massively cut environmental damage – resulting in 75% less climate-heating emissions, water pollution, and land use. We need a bold shift toward a food system that values sustainability, justice and life.

Because the climate can’t wait, and neither can we.

Update *14th July 2025* Article thumbnail and header image updated to remove illustrated imagery. Replaced with images that more accuratly represent the feed additives used in industry.

Are Italian apples really six times healthier than American apples?

Claim: Apples in Italy are more nutrient dense than in America

Fact-Check: Many factors impact nutrient quality of apples.

Nutrient levels in fruits like apples do vary based on several factors:

Variety: There are approximately 7000 cultivated varieties of Malus domestica known worldwide, such as Royal Gala, Bravo, Granny Smith, Green Star, Fuji, and Golden Delicious. Nutrient composition, especially polyphenol content, which has positive links to human health, varies among them. For example, Red Delicious has about 207.7 mg of phenolic compounds per portion, while Golden Delicious has around 92.5 mg.

Soil & Climate: Soil health, determined by biological activity, mineral composition, pH, and contamination, can impact nutrient uptake. Climate, irrigation, and orchard management practices (like fertilisation and pruning) also impact nutrient density and fruit quality.

It is important to note that these factors differ not just between countries, but also between regions and even individual farms in both the U.S. and Italy, so blanket statements comparing apples in Italy and in America lack context.

Storage & Processing: Phytonutrients can vary in apples depending on ripeness, season, and especially how the fruit is stored and processed. Cold storage, while essential for preservation and transport, can significantly reduce nutrient levels over time. Research shows that prolonged cold storage may decrease total phenol content by up to 50% in the flesh and 20% in the peel, due to the natural instability of these compounds.

Processing methods also matter. High temperatures, such as those used in drying or pasteurisation, can degrade nutrient compounds. As a result, apples that are stored for long periods or heavily processed may contain fewer beneficial nutrients than freshly harvested ones.

But here's the key: there is no evidence that nutritional variations are significant, let alone 6-fold, as the claim suggests.

Freshness does not equal nutritional density

Shayna Taylor’s claim that American apples offer only a fraction of the nutrients found in Italian ones relies heavily on the idea that Italian apples are "fresher" and therefore more nutritious. Perceived freshness and healthiness is indeed often cited as significantly determining consumers’ choices. Italian apples may feel fresher to a consumer, but that doesn’t mean they’re significantly more nutritious. Apples in the U.S. can be just as fresh, depending on source and timing. And even apples stored for weeks still offer meaningful health benefits. Italy and the U.S. could equally have apples available at local fruit markets and pre-packaged apples in larger stores.

What else impacts perceived freshness?

The claim appeals to the idea that food in Europe is better than in the U.S. A big part of why European fruit and vegetables may taste better to visitors is linked to culture, shopping habits, and spending. In countries like Italy and France, people often shop at small local markets several times a week. These shorter supply chains mean produce may reach the plate faster than supermarket imports. Europeans also tend to spend a higher share of household income on food. While this trend is also growing in the U.S. (source), surveys show that as inflation rises, Italians say they are ready to make other sacrifices in order to keep buying high quality produce. This might mean buying high-quality, locally grown produce on a more regular basis.

Eating behaviours can also change during tourism (source): American tourists or expats in Europe are more likely to buy fresh fruit from local markets or eat seasonal produce at restaurants, a very different experience than grabbing pre-packaged fruit from a chain store back home. This can reinforce the belief that European fruit is always better, when much of the difference is about context, not inherent nutritional superiority.

This is important, because claims like this misrepresent real differences, such as local farming practices or shopping culture, and replace them with a false notion that products are only worth eating when they come from selective sources.

For millions of Americans, affordable, local apples are an important source of nutrients. Many communities already face barriers to fresh food access, with millions living in food deserts. Almost 2 million households in America live far away from a supermarket and are without a vehicle (source), making access to fresh food products extremely difficult. Discouraging people from eating what is available, and perfectly healthy, only fuels confusion and anxiety about food quality.

Final Take Away

There’s no credible evidence that you’d need to eat six American apples to equal one Italian apple in nutrients. What matters more is eating fresh produce regularly, from any good source you can access. Wherever you live, choosing an apple, instead of perhaps skipping fruit altogether, remains one of the simplest ways to add fibre, antioxidants, and crunch to your diet.

Claims like this can do more harm than good. Yes, the American food system is in need of improvements. But in a context where 95% of Americans do not consume enough fibre (source), claims that could lead to distrust of ‘even the humble apple’ won’t achieve the type of change that is needed.

We have contacted Gary Brecka and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Look for evidence: Reliable claims should be backed by scientific studies or data.

During a recent episode of The Ultimate Human Podcast, Gary Brecka’s guest Shayna Taylor compared the nutrient density of American and Italian apples, claiming that in America, you would need to eat six apples to get the nutrients from one apple.

Comparisons between the quality of food products in America and European countries, especially Italy, are very popular on social media. In this fact-check, we explore the scientific evidence behind this claim.

Full Claim: "It's like an apple in America, you eat one and you actually only get the nutrients that is like a quarter of an apple and then, so you have to eat six apples in order to get the nutrients of one apple. Whereas when you go to Italy and you eat a tomato or an apple you're like "Whoa this tastes so good." And it's like "Well yeah." And it's nutrient dense." (37:50') [29th April 2025]

While nutrient levels in apples can vary due to variety, soil conditions, and storage methods, there is no scientific evidence supporting such a dramatic difference between U.S. and Italian apples. Apples from both the U.S. and Italy can be nutritious and beneficial to health.

Claims like this not only misrepresent the actual nutritional differences between produce from different countries, they also risk undermining a much more important and well-supported message: eating apples, regardless of where they're grown, is consistently associated with positive health outcomes.

By promoting the idea that only Italian apples are truly "nutrient-dense," the claim may discourage people from eating perfectly healthy, accessible options available locally. It creates unnecessary anxiety about food quality, undermines trust in domestic agriculture, and may lead consumers to overpay for imported goods under the false impression that they are dramatically superior.

Why do influencers keep saying that fruit makes you fat?

Final Take Away

Candi’s claims about fruit misrepresent established nutritional science and may discourage the consumption of a food group consistently linked to health benefits.

Selective breeding is a natural part of agriculture and does not make fruit unhealthy. Nor does pesticide use render fruit nutritionally equivalent to ultra-processed snacks. Claims that fruit might cause gestational diabetes or fat gain are not supported by evidence, which consistently shows that fruit can help protect against both.

Overall, fruit remains a vital part of a healthy diet and plays a key role in preventing chronic disease and supporting long-term health.

We have contacted Candi Frazier and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

The claim that “anything that produces insulin makes you fat” is vastly oversimplified. Many healthy foods such as fruits, vegetables and legumes can trigger insulin release without leading to weight gain.

Fat storage occurs when calorie intake consistently exceeds calorie expenditure, not simply because a food causes insulin to rise.

The increase in insulin that follows consumption of fruit (as well as with all carbohydrate-containing foods) is a normal physiological response, not a direct path to fat gain.

In fact, many studies have shown fruit can promote weight loss and prevent obesity. A systematic review found whole, fresh fruit consumption may promote weight maintenance or modest weight loss over 3–24 weeks. It also found fruit may help reduce energy intake and offer protection against long‑term weight gain. Similarly, another meta-analysis found increased fruit intake in children and adolescents was associated with a lower prevalence of obesity when compared to a control group.

So does fruit make you fat? In simple terms, no. As part of a healthy, balanced diet, fruit is far more likely to protect against weight gain than cause it.

Claim 1: “Fruit has been processed through selective breeding … It’s really not as natural as they think it is”.

Fact-Check: Let's begin by untangling the difference between processing and selective breeding, which are often confused, but are actually two very different things.

Selective breeding is ‘the intentional mating of organisms with desired traits to perpetuate those traits in subsequent generations’ (source). In simple terms, choosing plants or animals with beneficial characteristics and breeding them so that the offspring will contain those characteristics. These include better flavour, size, yield or resistance to disease.

It is not dissimilar from natural selection, just rather than the environment, it is human control that drives evolutionary changes. For thousands of years humans have used selective breeding to improve agriculture and ensure better quality and production.

While selective breeding takes place while the food is being grown, food processing refers to the mechanical or chemical changes made to the food after it has been harvested. This is generally done to help with food safety and storage as well as to enhance the flavour, texture and nutritional value of foods. Examples range from grinding grains into flour, to fermenting dairy to make yoghurt and cheese, as well as more industrial methods such as extrusion and hydrogenation.

So while it is true that selective breeding has changed fruit over time, this statement could be confusing because it conflates two distinct concepts: food processing and selective breeding.

This argument is also grounded in the appeal to nature fallacy, the idea that natural, unaltered foods are inherently better. Considering selective breeding is a technique that has been practiced for thousands of years on both plant and animal produce, by Candi’s logic almost all foods would be considered “unnatural”, which is an unhelpful way of viewing foods.

By separating foods into such rigid categories, of “natural” vs. “unnatural” or “healthy” vs. “unhealthy”, we lose important nuance and promote the belief that all food processing is harmful. In doing so, the benefits of food processing, and of selective breeding, get overlooked.

Additionally, there is no evidence that breeding plants is harmful. On the contrary, many studies have shown it can be used to improve nutritional profiles by increasing micronutrient content of certain foods. For example, using Orange Fleshed sweet potatoes to tackle Vitamin A deficiency (source, source), Quality Protein Maize, higher in essential amino acids, to address protein malnutrition (source ,source), and Iron Biofortified Beans to address iron deficiency (source).

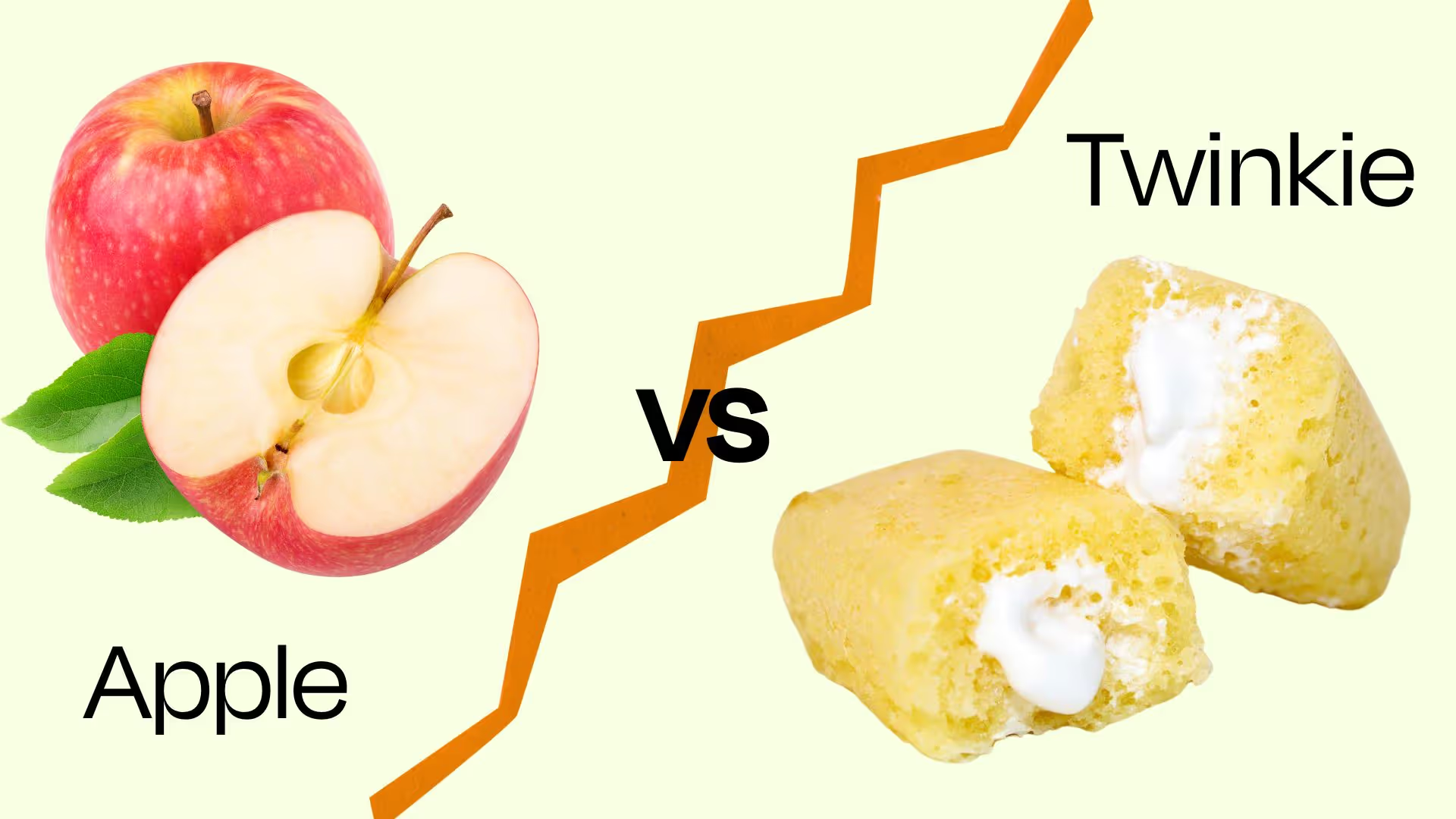

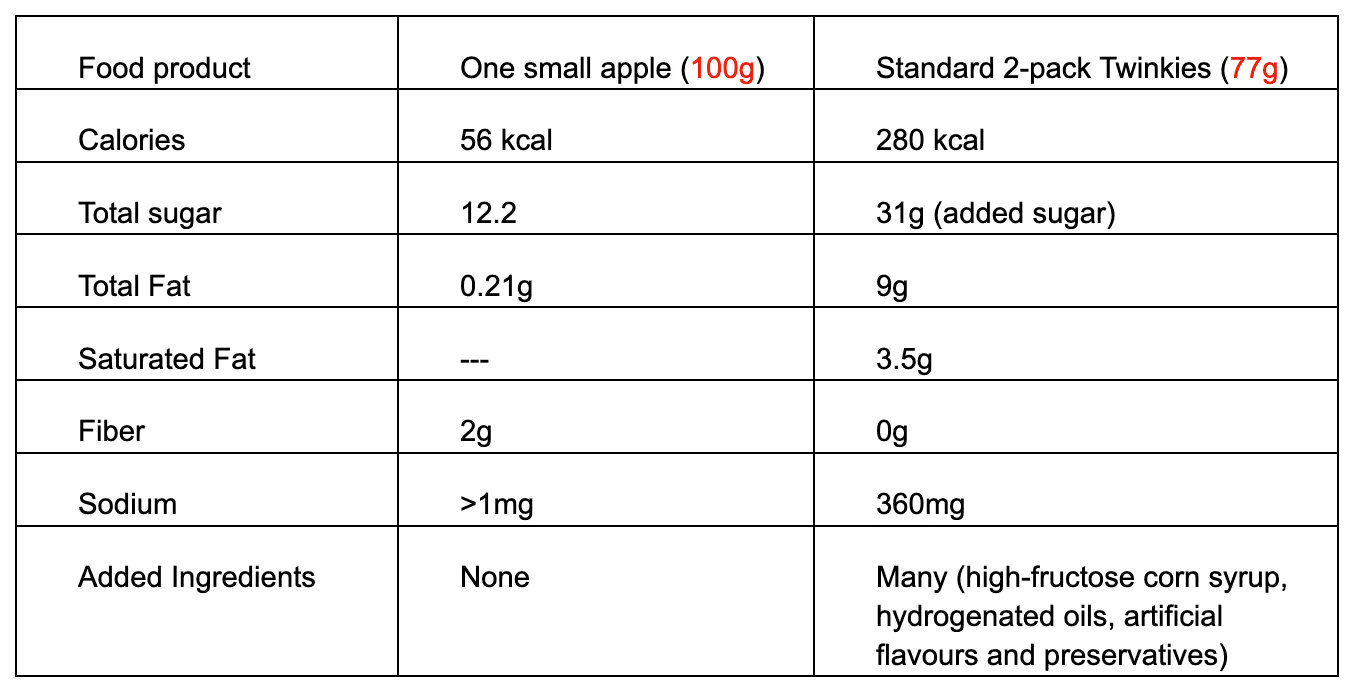

Claim 2: “Is it better than eating a Twinkie?... it’s really just a matter of toxins… if the apple is sprayed with pesticides and herbicides, probably not.”

Fact-Check: Here Candi implies that eating an apple sprayed with pesticides and herbicides is no different from eating a twinkie.

A look at the nutrition content of an apple and a twinkie tells us this is not the case.

Twinkies are a highly processed food, high in calories, saturated fat and added sugar. They have no fibre and contain many added ingredients like high-fructose corn syrup, hydrogenated oils, artificial flavours and preservatives (source).

Apples, on the other hand, are low in calories and saturated fat. They have no added sugars, and come in their natural form, unprocessed (as we’ve already established this is different from selective breeding). They are also high in fibre, vitamins, minerals and polyphenols (source).

Pesticides and herbicides are commonly used to protect crops from disease and control unwanted pests and weeds. The implication that consuming a pesticide-treated apple may be as harmful, or worse, than eating a Twinkie is highly misleading and not supported by scientific evidence.

In recent years there has been concern around the use of pesticides and herbicides, with certain pesticides being linked to diseases such as diabetes (source), metabolic syndrome (source) and some cancers (source). This is particularly in cases of chronic occupational exposure or in areas with poor regulation. However, the risk to consumers from dietary exposure is significantly lower and tightly regulated in most countries.

Large-scale assessments consistently show that pesticide residues found on fruits and vegetables are well below safety thresholds. For example, the European Food Safety Authority's 2020 report found that 94.9% of nearly 90,000 food samples were within the legally permitted maximum residue levels (MRLs), and dietary exposure was unlikely to pose a health risk to consumers (source). Similarly, a review in the UK found that only about half of food samples contained any detectable residues, and just 3.3% exceeded MRLs.

Moreover, simple practices such as washing, peeling, or cooking produce can significantly reduce any remaining residues (source).

Whilst the effects of pesticides are difficult to measure and still debated among scientists, the high amount of calories, saturated fat and sugar found in processed snacks like Twinkies are consistently associated with poor long-term health outcomes, including obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes. One umbrella review of meta analyses found ultra-processed foods were directly associated with 32 adverse health outcomes including ‘mortality, cancer, and mental, respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and metabolic health outcomes’ (source). Another mirrors these findings (source).

In contrast whole fruits like apples are consistently linked to reduced risk of chronic diseases (source).

When the benefits of eating fruits (and vegetables) are clearly outlined in scientific literature, the implication that we should avoid eating fruits just as we should avoid any type of ‘junk food’ risks promoting harmful dietary choices.

For more information on this topic, microbiologist and immunologist Dr. Andrea Love regularly shares clear evidence-based explanations related to pesticides use and residues, through her social media account and newsletter:

Claim 3: “My doctor at the time told me to not eat fruit while I was pregnant… It's gonna make you fat … you’ll end up with gestational diabetes.”

Fact-Check: Gestational diabetes (GDM) occurs when hormonal changes during pregnancy make the body’s cells less responsive to insulin, resulting in elevated blood glucose levels. It usually develops in the second or third trimester.

Large-scale meta-analyses have consistently identified the primary risk factors for GDM as older maternal age, excess weight or obesity pre-pregnancy and family history of diabetes (source, source).

One prospective study found that excessive fruit consumption in the second trimester, particularly fruits with a moderate-high glycaemic index, and tropical and citrus fruit may increase GDM risk.

Conversely, several high-quality studies have shown protective effects of consuming specific fruits against GDM. For example, one large cohort study found that women who consumed more fruits like blueberries, strawberries, blackcurrants or grapes had a 27% lower risk of GDM, with grapes alone associated with a 35% lower risk.

Further evidence from meta-analyses supports this. One meta-analysis found that total fruit consumption lowered GDM risk with a 3% reduction in risk of GDM for a 100 g/d increase in fruit consumption. Another reported a protective benefit of pre-pregnancy fruit consumption with a 5% lower risk of GDM among women who ate more fruit compared to those who consumed less.

Like all foods, fruit should be consumed as part of a varied and nutritious diet, but blaming it as one potential cause of GDM is misleading and not supported by current scientific evidence.

Claim 4: “Fruit does make you fat, it makes you produce insulin… anything that makes you produce insulin makes you fat… it’s the master fat storing hormone.”

Fact-Check: Candi’s last claim uses broad statements and overlooks the complexities of food and metabolism.

In a previous fact-check, we reviewed another claim she made about fruit consumption: that eating even half an apple a day could lead to visceral fat gain, due to excess glucose. This time she focuses more on the role of insulin.

So what actually is insulin? Insulin is an essential hormone released by the pancreas. Its main role is to regulate blood sugar levels. Following a meal, carbohydrates are broken down into glucose which then enters the bloodstream. In response insulin is released. This allows glucose to move into muscle and fat cells where it can be used for immediate energy or stored for future use.

While it's true that insulin can play a role in fat storage, attributing fat accumulation solely to insulin oversimplifies the complex interplay between hormones, diet, metabolism, and energy balance. The relationship is more nuanced, and context matters greatly.

Illustrating this point is one randomised controlled metabolic ward study, which compared two calorie- and protein-matched diets: one low in carbohydrates and one low in fat. Over the duration of the study, both groups experienced similar fat loss, suggesting total energy intake, not insulin levels, remains the primary determinant of fat change.

When it comes to fruit consumption, whole fruits are naturally rich in fibre, water, vitamins, minerals, and polyphenols, and generally low in energy density, which together may help promote satiety and support in managing overall calorie intake when consumed as part of a balanced diet. Fruit juices and dried fruits, however, are typically more concentrated in sugar and calories, and therefore may be easier to overconsume — so portion awareness is advised with these forms.'

Be cautious with absolutes like always, never, or the most dangerous; science rarely speaks in extremes.

On the 20th of May 2025 Candi Frazier, known as theprimalbod on Instagram, posted a reel containing a series of claims about fruit, and its role in health. Firstly, she states fruit has been “processed through selective breeding” and is therefore “not as natural as they think”.

Comparing fruit and junk food, she questions: “Is it better than eating a Twinkie?” and concludes “if the apple is sprayed with pesticides and herbicides, probably not.”

She goes on to detail how her doctor advised her to avoid fruit during pregnancy to prevent weight gain and gestational diabetes, concluding that “Fruit does make you fat… it makes you produce insulin… the master fat storing hormone.”

But do these claims hold up to science? Let’s break it down claim by claim and examine the scientific evidence behind these statements.

Fruit is a nutrient-dense food that offers important health benefits. As part of a balanced diet it can support weight management and lower disease risk.

Nutrition misinformation spreads rapidly on social media and can significantly influence real-life dietary choices, particularly during sensitive times like pregnancy. This video relies heavily on the appeal to nature fallacy, promoting unnecessary fear around safe, healthy foods. Over time, such messages can contribute to overly restrictive diets that lack essential nutrients. Fruit, for example, is a key source of fibre, a nutrient most people under-consume, despite its vital role in digestion, metabolic health, and disease prevention.

Why our vegetable marketing needs a serious rethink, starting with our kids

Have you heard of 'Punishment Juice'? Marketed humorously by M&S, this seven-vegetable concoction, including celery, kale, spinach, and spirulina, might seem innocently playful, but it actually reflects a serious problem in how we frame vegetables: as punishment rather than pleasure.

Commodifying Guilt: A Troubling Trend

The whimsical marketing of 'Punishment Juice' reinforces the problematic notion that vegetables are inherently unpleasant, a penance rather than a pleasure. Although tongue-in-cheek, such framing plays into adult cynicism about healthy eating, perpetuating disordered thinking and unnecessarily moralising food choices. In a society where diet culture is already prevalent, reinforcing guilt around food choices can be harmful, especially when this messaging trickles down to children.

Playful but Problematic

Campaigns like the highly successful "Eat Them To Defeat Them" have made significant strides in increasing vegetable consumption among children. By framing vegetables as 'evil invaders' to be conquered, the campaign cleverly turns a common childhood aversion into a playful challenge. But while effective, this strategy still suggests that vegetables are inherently unappealing and can deepen children’s resistance to eating them long-term.

A Global Perspective: Celebrating Vegetables

In cultures like Japan, vegetables aren't moralised or viewed as punishment. Instead, they’re deeply embedded into daily food rituals and treated as delicious, valued foods, seamlessly woven into cultural traditions without the baggage of ‘good’ or ‘bad’ labels.

This contrast highlights the shift our own food culture in the UK desperately needs.

Building a Better Relationship with Food

To truly foster healthier eating habits, we must rethink our relationship with vegetables, beginning with childhood experiences. Rather than presenting vegetables as obligatory or punitive, we should encourage exploration, participation, and joy.

Initiatives like the Hackney School of Food provide powerful examples of this approach. Here, children grow, pick, cook, and taste vegetables themselves, sparking genuine enthusiasm and pride in their culinary creations. Seeing five-year-olds eagerly sampling fresh sorrel from the garden or Year 5 students proudly preparing dishes with olives and sundried tomatoes vividly illustrates how a positive relationship with food can be nurtured.

Reframing Vegetables: Creativity Without Villains

It's entirely possible, and necessary, to craft creative, engaging marketing that doesn't villainise vegetables. By reframing vegetables as tasty, familiar parts of our everyday meals, we can build a healthier, more joyful food culture. Let’s inspire curiosity, participation, and enjoyment, rather than reinforcing outdated narratives of obligation and guilt.

After all, eating well should be delicious, celebrated, and free from judgement.

Latest fact-checks, guides & opinion pieces

.svg)