Beyond ingredient panic: how to make better food choices together

Nutrition discussions in the digital age: an evolving conversation

Social media has fundamentally changed how we communicate, and how we process information.

Take nutrition research, for example. Social platforms have opened up conversations around studies that, while always public, would once have broadly remained within academic circles. Now, more people than ever are engaging with nutritional science, sharing their experiences and tips about what healthy eating means.

But with this openness has come a new challenge: the rise of anecdotal evidence, often elevated above more robust scientific findings. Nutrition misinformation began to grow, and quickly.

Over time, the term misinformation itself became weaponised, used to defend disputed claims. What we’ve ended up with now looks more like a battle of who's right and who’s wrong than a constructive dialogue.

To be clear: misinformation is a real and urgent problem

Our recent report, written by Rooted Research Collective, highlighted how a small number of “superspreaders” account for a disproportionate share of false or misleading nutrition content, often with clear financial or ideological incentives.

Research into how information gets shared online has also shown that misinformation spreads faster than facts. Restoring a baseline of factual understanding and calling for accountability when sharing health information online is therefore essential.

But it's only part of the solution.

Channelling common ground

What often gets lost in these digital back and forths is how much underlying common ground exists between opposing sides.

Rebecca Gregson’s research on self-identified ‘anti-vegans’ in online communities found that, perhaps surprisingly, they share core beliefs with the vegan communities they oppose. Both groups, for example, agree that “humans have a responsibility to minimise the harmful impacts of their choices on animals and the environment.”

This insight reveals something important: even people with radically different viewpoints often want the same outcomes: better health, better systems, and better choices.

That’s why we are urging people to channel this common ground to start aiming at ‘the real enemy’ of nutrition information in this digital age, that is to say to focus on the issues that affect us all, the barriers that slow down meaningful change, rather than to fixate on distractions.

The false villains of nutrition

The search for a villain is one of the most powerful storytelling strategies on social media. It offers clarity, it’s emotionally charged, and it generates engagement (outrage, fear, righteous anger, agreement), all of which are highly profitable for content creators.

But in the realm of nutrition, this can lead to deeply misleading narratives.

Take the common claim that a particular ingredient “has been linked to cancer.” These claims are often based on studies in which animals were exposed to very high doses, or on mechanisms that don’t even apply to humans. And for someone without a scientific background, that sounds scary, and reasonably so. If there’s any risk at all, why take it?

That’s where distrust begins.

So why is this harmful?

Let’s use an analogy. Every time you get in a car, you’re taking a risk. You’re also making the decision that this risk is small enough for you to take it. For most people, these decisions are all made unconsciously. That doesn’t mean you’re ignoring the possibility of an accident or undermining its severe reality. It means you’ve assessed that the benefits outweigh the risk. You’re making a decision based on probability and understanding of risks, not fear.

Imagine what would happen if we started to consciously weigh up those risks every time we entered our car. And now imagine what would happen if we started thinking this way about our food. Without an understanding of mechanisms, dosage, or scientific context, we can start treating food like a minefield, as though any bite could trigger disease.

Once fear takes root, it starts to shape the way we make choices. We begin to overly focus on single ingredients, and this distorts our sense of what well-balanced nutrition actually looks like. Real public health issues fade into the background, replaced by distractions: artificial dyes, seed oils, emulsifiers.

Meanwhile, we overlook far more pressing and well-documented concerns:

- Most people under-consume fibre; yet access to fresh, whole fruits and vegetables is harder than access to junk food for large parts of our population;

- Marketing heavily favours convenience and profit over nutrition;

- Many people don’t have the time, resources, or knowledge to cook nutritious food.

These are issues that demand structural change, change that would be facilitated if we all put our energy behind it. They’re not systemic issues we ignore, they’re issues that most of us agree with, regardless of dietary views:

That our food system doesn’t support health.

That we need to refocus on whole foods.

That convenience and profit have overtaken the food landscape.

That we’re now seeing lasting damage.

In other words: there is shared concern beneath the noise. And if we want to move forward, recognising that common ground is essential. Because one of the deepest consequences of this culture of conflict has been a growing distrust in experts.

So who is the real enemy?

It’s not seed oils.

It’s not single additives.

It’s not your doctor, your pharmacist, or nutrition scientists.

The real enemy is:

- Profit-driven food industries that prioritise profit over health;

- Confusing marketing that makes unhealthy foods seem like health solutions or hacks;

- A society that makes healthy choices the harder ones: through time poverty, cost barriers, and systemic inequity;

- A culture of fear that distorts risk and feeds off outrage.

Let’s refocus

The term misinformation often directs our focus toward factual accuracy. And while accuracy matters, it is only half the story. Just as damaging is miscommunication, the way nutrition science gets packaged, framed, and circulated.

Online platforms don’t simply spread information; they shape how it is received. Algorithms reward sensationalism, simplicity, and fear. What gets lost is balance, nuance, and context, which are all essential to nutrition. Over time, the issue extends beyond inaccurate claims. It changes the way we think about food itself, fostering a culture of hyper-fixation, distrust, and fear.

If we want real change, not just better nutrition information online, but real progress in public health, we need to channel our common ground and start asking better questions:

- Who benefits from this narrative?

- What does the evidence actually say?

- Are we reacting from fear, or responding with context?

One critical step in this direction is to advocate for accountability on social media platforms whenever nutrition or health related claims are made. This would help to minimise the spread and prevalence of misinformation by reducing the appeal of sensational, over-simplified statements. In other words, accountability would support the public to make decisions based not on fear, but on understanding. So let’s stop fighting each other, and instead redirect our energy towards our common goal: improving our food system to make it more sustainable and health-promoting.

Untangling microwaves myths: a physics-based reality check

Step 2. What does heating do, and how do microwaves work?

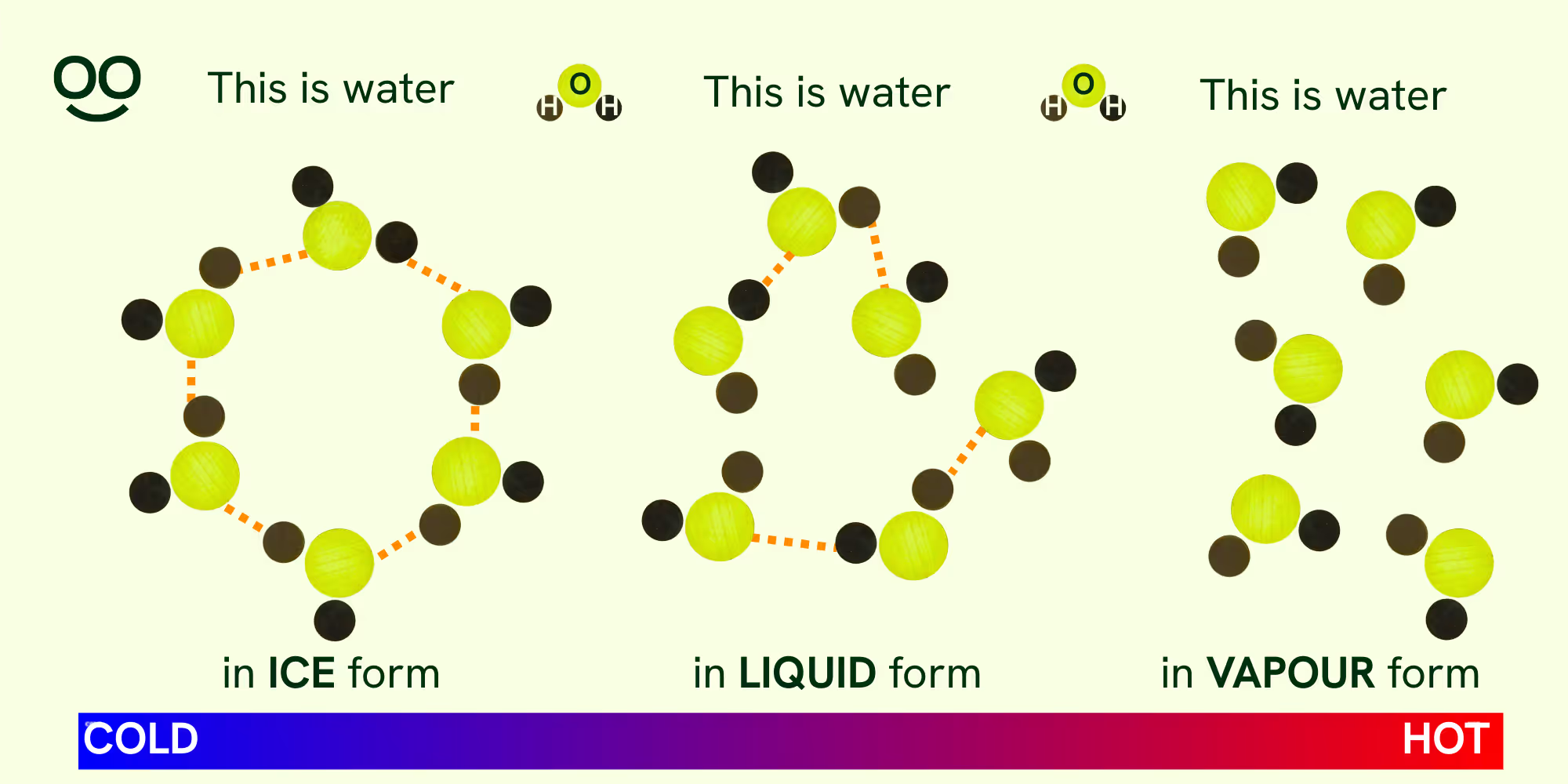

Heating means adding energy so molecules vibrate faster, which we feel as higher temperature.

While a stove transfers heat from the outside in by conduction, a microwave directly targets water molecules within the food, spreading heat from inside out. Microwaves heat water by making the molecules wiggle faster, which raises the temperature.

So how does this work?

Microwaves are a form of electromagnetic energy made up of oscillating electric and magnetic fields. When these fields interact with polar molecules, molecules that have a positive side and a negative side, they cause them to rotate back and forth in step with the field. Water is a polar molecule, so when exposed to microwaves, its molecules oscillate rapidly. This motion increases their energy, which we experience as heat. All food contains water, and so this method of directly targeting water molecules is an effective way to heat up food.

Think of a water molecule as shaking a maraca. Shaking makes the beads rattle, just like microwaves make a water molecule jiggle. But shaking doesn’t smash the maracas apart. Similarly, microwaves heat food by jiggling a water molecule, they don’t break apart the bonds that make water, water.

Claim 3: Microwave heating changes food so much that your body doesn’t recognise it.

Gubba claims that “it's not just about nutrients being lost. It's about eating something your mitochondria don't even recognise.” Let’s step back to assess whether microwave heating affects food differently compared to other methods of cooking.

What does cooking normally do to food?

Cooking always affects food molecules. Proteins “denature”: this means they unfold and take new shapes. That’s why a raw egg turns from clear to white when heated (source). This denaturation process involves the same mechanisms as mentioned above, that is it affects the weaker hydrogen bonds between molecules, rather than the covalent bonds that make up primary structure.

Any form of cooking (steaming, boiling, roasting) changes the shape of proteins and the arrangement of molecules. That’s what cooking is. Proteins denature, starches soften, fats melt, water evaporates. These changes are not the same as creating a harmful or “foreign” substance for your body; they’re part of normal food preparation. In fact, denaturing proteins through cooking makes them easier for our digestive enzymes to break down (source).

What about nutrient loss?

Research shows that due to its heating efficiency and shorter cooking time, nutrient loss is less prevalent when food is heated up in microwave ovens, compared to other methods of cooking.

Again, the loss of vitamins is a natural effect of cooking. But on the plus side, cooking also helps to destroy harmful pathogens.

Bottom line

From a physics perspective, microwaves don’t do anything mystical to your food. Cooking in a microwave and cooking on a stove both “boil down” to the same thing: increasing the vibrational energy of molecules. Microwaves just use a different route to get there, targeting water molecules directly. They heat it by exciting water molecules, just as other cooking methods raise temperature in different ways.

Why these conspiracy-style claims spread

Conspiracy theories often appeal to a general sense of distrust, particularly distrust of modern technology. They can be convincing because they work with topics that are inherently complex, then modify the science to sound plausible. In the case of microwaves, the idea taps into a natural instinct: trusting “older” ways of cooking over modern inventions.

But science moves us forward by helping us understand more, not less. With that understanding comes safety. The principles behind microwaves aren’t hidden away in some lab; physics and chemistry are taught in every school, giving us the tools to question extraordinary claims.

We have contacted Gubba Homestead and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

So what do microwaves actually do?

We have seen that microwaves don’t have enough energy to break the covalent bonds that link the oxygen atom to each of the two hydrogen atoms within single water molecules. Instead, what microwave heating does is to loosen the weaker hydrogen bonds between separate water molecules.

But this does not affect the structure of water. Those hydrogen bonds loosen and strengthen naturally as water changes state: solid ice (strong hydrogen bonds), liquid (weaker bonds), and steam (almost no bonding). When water turns to steam, hydrogen bonds weaken and break. That’s just heating, no matter the method, and it’s reversible when it cools.

Claim 1: Microwaves were banned in the Soviet Union because they were dangerous.

The video says Soviet scientists discovered microwaves were so harmful that the USSR banned them outright in the 1970s.

Step 1. What would banning them imply?

To evaluate the claim that the USSR banned microwaves because they were dangerous, we need to consider what such a ban would imply: either confirmed evidence of harm, or precautionary measures based on perceived risks.

This hasn’t happened, and it’s important to note that the studies which Gubba claims led to a microwaves ban are not listed. On the other hand, this review of studies on microwaves safety concludes that “the best available evidence supports that the use of microwave cooking resulted in foods with safety and nutrient quality similar to those cooked by conventional methods, provided that the consumers followed the given instructions.”

No credible source confirms any formal government policy banning microwaves in the USSR.

Step 2. What actually happened?

There’s no evidence that such a ban ever happened. Conspiracy theories often rely on the idea that powerful groups hide important truths from the public, so simply pointing out the lack of records may not feel convincing on its own.

But in this case, first-hand historical testimonies and lived experience contradict the claim: from renowned engineers providing primary evidence that microwave ovens were not only available, but researched, developed and sold in the USSR during the 1970s and 1980s (including ads for Russian-developed microwave ovens), to Reddit threads from Russian users recalling usage of microwave ovens at the time they were supposedly banned.

The ban story survives online because it sounds dramatic, not because it reflects reality.

Claim 2: Microwaves violently agitate water molecules in a way that scrambles their structure, leaving you with something “energetically incoherent”

In other words, the video suggests microwaves don’t just warm food, they shake water molecules so violently that the molecules themselves become “scrambled” and lose their chemistry.

Step 1. What is water made of?

To fully understand this claim, we need to step back and look at what water is made of. Water is H₂O: one oxygen atom strongly bonded to two hydrogen atoms. Each individual molecule’s oxygen and hydrogens are bonded by covalent bonds.

Changing the structure of water as is claimed would involve either breaking the water molecule’s covalent bonds apart, creating hydrogen and oxygen; or ionising the molecule, which means adding or removing an electron(s).

Why the claim doesn’t add up

Microwave photons don’t carry enough energy, required by the principles of quantum mechanics, to break covalent bonds or to strip electrons. Our following Expert Weigh-Ins provide detailed information to explain this:

For a residential microwave oven, the microwaves used are of a nominal frequency of 2.45 Gigahertz, which translates to about a 12.2 cm wavelength.

Energy would then come out to be E = 1.62 x 10^-27 Joules. Converted to an easier unit of measurement, this value is about 1.0 electronvolt.

The minimum amount of energy needed to break a water molecule into hydrogen and oxygen is 7.7 electronvolt of energy.

We also know from quantum mechanics that energy is quantized and can only be absorbed in discrete packets. In other words, if a "photon" does not have energy equal to the energy it takes to break the bond between hydrogen and oxygen, it will not be absorbed.

So we can obviously see that the amount of energy in microwave radiation is much lower than than the energy required to break the covalent bond between hydrogen and oxygen. So the chemistry of water will not change.

Secondly, microwaves are a form of non-ionising radiation. Essentially, microwaves do not have enough energy to remove an electron from an atom and cause ions.

For example, the ionising energy of one hydrogen atom is 13.6 electronvolt, and the one for oxygen is 12.03 eV. This means that microwaves leave no lasting effect on the food.

Even though the method of heating the food is different in microwave ovens vs heating the food on a fire or heat source, the principle is the same: heating something requires increasing the energy of vibration of the molecules. Unless you provide a large enough amount of energy in one photon, it will not lead to the breaking of atomic bonds which require a high amount of energy to break.

However, the energy is usually large enough to break or change the intermolecular bonds, such as hydrogen bonds, hence causing a change of state from liquid to vapour for example.

Be skeptical of dramatic health claims that aren’t backed by data or evidence. If you can’t find support from peer-reviewed studies, reputable scientific bodies, or clear historical records, that’s a sign to pause before sharing.

This fact-check is slightly different from others on Foodfacts.org. The claims we’re addressing come from a popular video by ‘Gubba Homestead,’ which presents microwaves as a hidden danger using arguments that resemble common conspiracy-style narratives. These claims can sound convincing because they use scientific terms in confusing ways.

We’ll go claim by claim, stepping back to break down the logic behind each claim, in a way that makes sense without pre-existing extensive knowledge of physics or chemistry. And if you wish to dig even deeper, look out for our Expert Weigh-In sections, which include direct insights from a physicist who analysed these claims.

The rumour of a Soviet ban has been disproved by historical records and expert testimony. Physics shows that microwave photons don’t have nearly enough energy to break chemical bonds or ionise atoms. Cooking in a microwave works the same way as other methods: it raises molecular motion, denatures proteins normally, and often preserves more nutrients thanks to shorter cooking times.

These claims spread because they sound scientific while playing on distrust of technology. Left unchallenged, they fuel conspiracy-style thinking and create confusion about everyday kitchen tools. Breaking them down shows how science and evidence give us safer, clearer answers than instinct or rumour.

Are vegans really destroying the planet with avocados?

Few food debates get recycled as often as the claim: “Vegans are destroying the planet with their avocados!” It’s a neat rhetorical trick—call out a trendy plant-based food with documented environmental issues, and suddenly all of veganism looks hypocritical.

But here’s the thing: it’s a red herring. This argument doesn’t hold up under scrutiny, and worse, it distracts from the real work of fixing our broken food system.

1. Meat eaters eat avocados too (and more of them).

Let’s start with the obvious: avocado consumption is not a vegan phenomenon. In the U.S., per capita avocado consumption has quadrupled since the early 2000s, driven largely by mainstream omnivorous diets. Think:

- Avocado on turkey sandwiches

- Chicken-and-avocado wraps

- Bacon-topped avocado toast

- Mountains of guacamole at sports bars

A quick reality check: only about 1–2% of people identify as vegan, so even if every vegan lived off avocados, they wouldn’t come close to driving global demand. This is not a “vegan” problem—it’s a food system problem.

Blaming vegans for avocados is like blaming cyclists for traffic jams because they also use the road.

2. Avocados are not a “meat replacement”—it’s a false equivalence.

The avocado-as-meat-substitute narrative misunderstands both nutrition and plant-based eating. Avocados are prized for their fats and flavor, not protein. They aren’t eaten “instead of” meat; they’re eaten alongside other plant proteins like legumes, tofu, or nuts.

A typical avocado has around 3g of protein. Compare that to:

- 100g of chicken breast: ~31g protein

- 1 cup of cooked lentils: ~18g protein

- 100g of tempeh: ~20g protein

So, no one is swapping steak for avocado. Framing it this way suggests that vegans are single-handedly fueling avocado demand because they’re using it to replace meat, which is simply untrue.

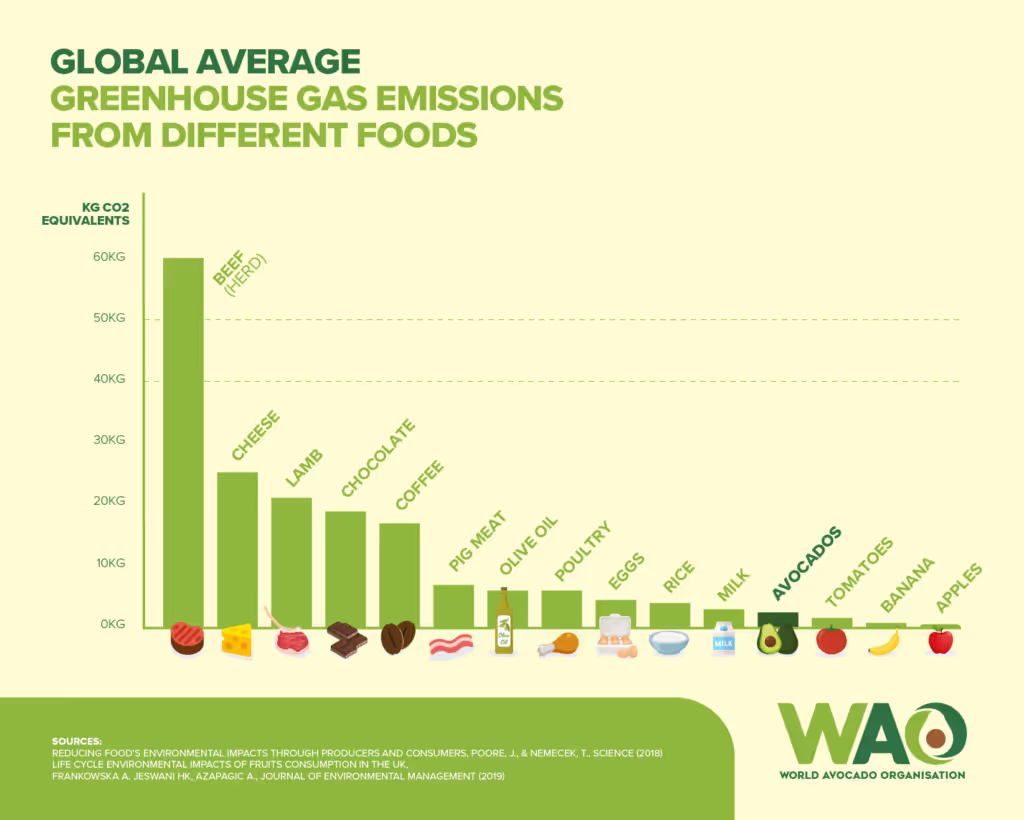

3. Even with their issues, avocados beat meat and dairy on every metric.

Avocado farming has legitimate concerns: high water demands (especially in arid regions), monoculture practices that degrade soil, and in some cases, links to cartel-controlled supply chains in Mexico. These issues deserve serious attention.

But here’s the context rarely mentioned:

- Producing 1kg of beef emits ~60kg of CO₂e on average.

- 1kg of avocados emits ~2.5kg of CO₂e (even when imported by air, which is rare—most avocados are shipped by sea).

- Beef uses 20x more land and roughly 10x more water per calorie than most plant foods, avocados included.

Even dairy—often considered a “lesser evil”—has a higher footprint than avocados. So if we care about environmental impact, avocado toast is still light years ahead of a cheeseburger.

4. The avocado argument distracts from systemic issues.

What’s really going on here? The avocado critique functions as a conversational derailment. Instead of examining meat and dairy—industries that dominate agricultural emissions and land use—we pick on a trendy plant-based food and blame a small minority.

This framing does two things:

- It shifts responsibility away from industrial animal agriculture, the elephant in the room.

- It positions plant-based diets as hypocritical, discouraging shifts that are objectively better for the planet.

It’s a distraction, not a solution.

So what should we be talking about?

If we care about food sustainability, there are real conversations worth having:

- Diversifying crops: Monocultures (avocados, soy, corn) strain ecosystems regardless of diet. How do we promote regenerative practices and more varied planting?

- Reducing overconsumption: Overeating resource-intensive foods—animal or plant—creates unnecessary pressure on the system.

- Improving supply chains: Ethical sourcing, better water governance, and worker protections are critical for both plants and animals.

These are complex, systemic issues. And they’re solvable—but not if we waste time blaming a fruit.

Bottom line

Avocados aren’t perfect. Neither is any crop. But holding them up as proof that plant-based eating is hypocritical is intellectually lazy. It misplaces blame, ignores data, and sidelines the urgent need to reform how we grow and consume food across the board.

If we’re serious about sustainability, let’s have real conversations about systemic reform—because arguing over avocados is, frankly, small potatoes.

Fibre under fire: debunking Eddie Abbew's claims that humans don’t need it

We have contacted Eddie Abbew and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Digestive health supports the immune system

About 70% of the immune system is housed in the gut (source). A well-balanced microbiome helps protect against pathogens and modulates immune responses, reducing inflammation and risk of infection.

Digestive health supports mental health (gut-brain axis)

The gut and brain communicate through the "gut-brain axis." While the gut-brain axis is not new, it has seen a surge in interest recently, with research consistently highlighting “how the gut and brain are deeply interconnected and influence each other in ways that affect our overall health, emotions, and behavior” (source). An unhealthy gut is linked to the development and progression of mental health issues like anxiety or depression, possibly due to inflammation and neurotransmitter imbalances (source, source).

Digestive health helps to prevent chronic diseases

Poor digestive health and gut imbalance (dysbiosis) are associated with conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Beyond gut-related conditions, extensive research has shown associations between increased dietary fibre intake and a reduced risk of many conditions including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and colon cancer.

Final take away

Eddie is right to say that the typical Western diet is causing health issues. But here’s the twist: research shows the opposite of what he suggests: that these health issues are partly due to a lack of fibre (source).

Let’s finish with Eddie’s claim that we (presumably, this refers to we in the West) are being “brainwashed” into thinking fibre is good for us. Brainwashing usually refers to the use of pressure to adopt beliefs or attitudes. If that was really the case, efforts to “brainwash” Westerners into increasing fibre intake would be clearly failing. Why? Because the data shows precisely the opposite. In the US, 95% of the population falls short of fibre consumption recommendations, with inadequate intakes prompting a public health concern (source).

This massive discrepancy seems to stem from a misconception of what a standard Western diet looks like. Eddie Abbew implies that it might be packed with fibre, and high in refined carbohydrates. Reality paints a different picture, that of a diet that is too high in refined carbohydrates, in sugar and saturated fat, mainly due to an over-reliance on ultra-processed products - foods which lack in… fibre.

Claim 1: “There is no scientific proof that humans need fibre.”

Fact-check: This claim ignores a large body of scientific research and consensus (source). While fibre isn't classified as an 'essential nutrient' in the strictest biological sense, its role in maintaining health and preventing chronic disease is strongly supported by high-quality evidence from large-scale studies and clinical trials.

What fibre does…

The claim that humans don’t need fibre is based on the classification of some nutrients as essential. In a more recent video, Eddie Abbew continued to argue that fibre isn’t ‘for humans’, on the basis that it doesn’t break down. Let’s unpack these claims to better understand the role played by fibre and more generally by food to support the body’s needs.

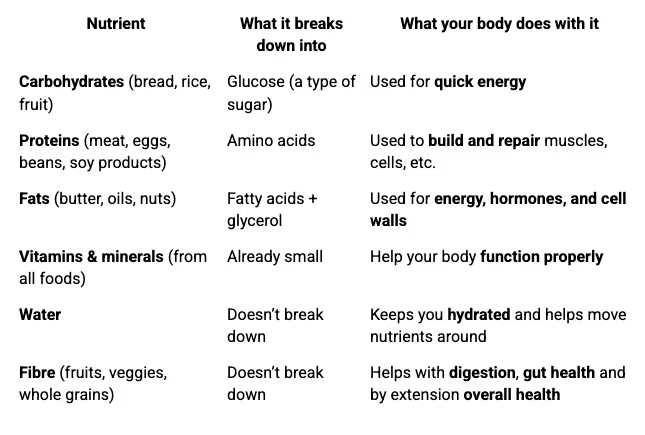

When you eat food, your body digests it, which means it breaks it down into smaller parts so it can absorb the nutrients and use them for energy, growth, and repair.

Essential nutrients are then classified based on their necessity for survival: these are compounds the body cannot synthesise (or cannot make in sufficient amounts), such as certain amino acids, fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals. Without them, deficiency diseases or death can occur.

Dietary fibres don’t fall into that category, because they aren’t absorbed or digested. But that doesn’t make them unimportant. It’s like saying a tool isn’t essential because it’s not part of the final product. The role of dietary fibres is to help digestion to work optimally, which has wide-ranging effects on the whole body (source).

Think of food like a Lego structure, where essential nutrients are the individual Lego bricks that your body uses, and digestion helps to take the Lego apart. Fibre isn’t one of the Lego bricks, but it’s a vital tool that helps ensure the entire process works smoothly.

Let’s go through the main parts of food and what happens to each:

The British Dietetic Association summarises fibre’s role in in that way:

“Fibre is essential for your gut to work normally. It increases good bacteria which supports your immunity against inflammatory disorders and allergies. A high fibre diet seems to reduce the risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and bowel cancer.”

We can see that there are crucial interactions at the heart of this process, so looking at nutrients in isolation paints a misleading, incomplete picture. It’s also important to remember that fibre-rich foods contain other essential nutrients like vitamins, minerals, protein and antioxidants.

Adequate intake recommendations for fibre are therefore set for optimal health. In the US, the average recommendation is 28g/day, and in the UK, updated advice has increased these to 30g/day. There is also evidence showing that over 30g/day would offer more benefits (source).

… and why it matters

Fibre helps everything work smoothly in a few different ways, which we have outlined here based on different types of fibres:

- Insoluble fibre (like wheat bran):

Insoluble fibre doesn't dissolve or ferment much, but keeps your digestion moving. It acts like a sponge, soaking up water and bulking up your stool. This helps prevent constipation and reduces the time waste stays in your gut, which is important for gut health.

- Soluble fibre (like beta-glucans or psyllium husk):

Soluble fibre forms a gel in your gut that slows down how quickly things like sugar and cholesterol are absorbed. This can help stabilise blood sugar, reduce cholesterol, and support heart health. It also helps you feel full longer, which can reduce overeating.

- Fermentable fibre (like pectins or inulin):

Fermentable fibre gets broken down by your gut bacteria (fermentation). This produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), tiny compounds that act like messengers in your body. SCFAs help regulate hunger by stimulating hormones that make you feel full, support your immune system and reduce inflammation and play a role in balancing energy use and fat storage.

Claim 2: “Most people doing the Carnivore Diet will tell you that they’ve reversed chronic metabolic conditions, they’ve felt the best they’ve ever felt, they’re full of energy, their skin glows better.”

Fact-check: This is what’s known as anecdotal evidence: individual stories that may reflect real experiences but aren’t reliable on their own for drawing conclusions.

Eddie Abbew claims that most people on the Carnivore Diet have positive experiences. One recent study did report similar findings. However, the participants were self-selected among a group of people having followed the diet for over six months. This means the results likely reflect a biased sample of people who already had good experiences and were motivated to share them. On the other hand, most people experiencing negative outcomes are likely to stop the diet before six months.

Relying on anecdotal evidence is like using one single review to judge an entire restaurant, without looking at any others. Social media makes this even worse, because algorithms keep feeding you more of what you already believe. There are plenty of people who’ve had negative experiences with the Carnivore Diet, they’re just not the ones going viral. But if you search for “why I quit the Carnivore Diet” on platforms like YouTube and scroll through the comments, you’ll start seeing some of them.

The main issue here is that anecdotal evidence is being used as the sole justification for a conclusion on the benefits of a diet, which is presented as the best way to eat for most people.

Let’s compare that to how science works.

We often ask, “What does science say?” That question isn’t just about what results show: it’s about how those results were found. Following anecdotes that some people reported feeling better on the Carnivore Diet, science would ask whether any other factors might explain that feeling. For example: could the benefits come from cutting out ultra-processed foods, rather than eating only meat?

Science starts with a question. It forms a hypothesis. Then it tests that hypothesis. That’s very different from starting with a belief or idea, and then sharing points that support it. That’s just not how science works.

When it comes to the Carnivore Diet, there’s very little long-term data. That’s partly because it would be unethical to run a randomized controlled trial asking people to follow a diet that may lead to nutrition deficiencies (source). While some people might report feeling better after starting the Carnivore Diet, this doesn’t tell us anything about long-term consequences. And the thing is: you don’t feel heart disease developing. That’s why long-term studies are essential to understand the full picture of health impacts.

So, what does science say about fibre?

Eddie’s claim is focused on the suggested benefits of the Carnivore Diet to reverse chronic conditions. This is a broad statement, and various, tailored diets might be best suited depending on the condition. However, there is ample evidence pointing to the benefits of fibre (which is lacking in a strict Carnivore Diet) when it comes to managing or preventing a range of chronic conditions.

The latest research shows that the impact of dietary fibre extends beyond the gut (source). Fibre shapes the gut microbiome, fueling beneficial bacteria to produce metabolites like short-chain fatty acids that strengthen immunity, regulate metabolism, and protect against chronic disease (source, source, source, source).

Therefore digestive health is vital not just for digestion, but for immunity, disease prevention, and overall well-being. Taking care of your gut means taking care of your whole body.

Claiming that fibre is “not essential for human health” is nutrition misinformation of the highest order.

Personal anecdotes can be interesting, but they are not a substitute for decades of high quality research.

We know from countless studies that a diet rich in fibre from fruits, vegetables, whole grains, beans, nuts, and seeds supports better digestion, a healthier weight, improved blood sugar control, and lower risk of heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and colon cancer. Fibre feeds the trillions of microbes that live in your gut and in turn those microbes help regulate your immune system, metabolism, and even your mood. Human health depends on a rich variety of plants and the fibre they contain.

If an individual experiences unusual symptoms when eating certain foods - including itchiness or any arbors suggestive of a true food allergy - it's important to seek professional advice rather than dismissing entire food groups. For the rest of us, putting plants at the centre of the plate remains one of the most powerful steps we can take for long term health.

Eddie Abbew's claim that people only need fibre because they're eating "high-carbohydrate grains that have been stripped of all nutrients" presents a fundamental misunderstanding of its role. This frames fibre as a mere antidote to an unhealthy diet, rather than the cornerstone of good health.

The core issue with processed grains isn't just a lack of "all nutrients"; the most significant loss during refining, which removes the bran and germ, is dietary fibre. This is critical because fibre's benefits are inherent and far-reaching, regardless of other dietary choices. Fibre, in its own right, is vital for gut and digestive health, disease prevention, blood sugar control, and even weight management.

Look for evidence: Reliable claims should be backed by scientific studies or data.

Influencer Eddie Abbew recently posted a video in which he shares his own dietary habits, explaining the reasons why he chooses not to eat fruits and vegetables. While these are personal choices, he also goes on to say that there is no scientific proof that humans need fibre, a type of carbohydrate found in plant-based foods.

In this fact-check, we break down the reasoning behind the claim that fibre isn’t essential, assessing its validity against the latest available evidence and recommendations.

While fibre isn’t classified as an essential nutrient, its role in supporting digestion, immunity, and long-term health is well established in scientific research. Claims that humans don’t need fibre overlook how it supports vital functions throughout the body.

Amid widespread public health recommendations to increase fibre intake, viral social media posts claiming to avoid fibre entirely, and feel better for it, can understandably cause confusion. That’s why it’s important to understand the scientific foundation behind these guidelines. Knowing how nutrition advice is built can help distinguish between evidence-based recommendations and personal opinions that may not apply to everyone.

Toxic bread or TikTok panic? What you should know about azodicarbonamide (aka the yoga mat chemical)

Claim 1: “Bread like this has a yoga mat chemical in it to fluff it up just like a yoga mat.”

Fact-check: This claim is misleading because it appeals to a fallacy of equivalence: comparing ingredients that we regularly consume with the production of synthetic products can sound very scary without context. Let’s break down the facts to understand why this is not a meaningful comparison.

What is Azodicarbonamide? And can it break down into harmful chemicals?

Azodicarbonamide (ADA) is a chemical with different uses. As a food additive it can be used as a bleaching agent and dough conditioner, to improve texture and shelf life of bread. It is also used in food packaging to seal glass jars and bottles (source), which is actually a more significant source of contamination in food than its use in bread (source).

In non-food settings, it is used as a blowing agent to create foamed plastic and rubber products such as yoga mats and shoe soles (source).

Phillips isn’t wrong that ADA can break down during baking. When flour is dry ADA is stable, however when it is moist, as is the case during the bread making process it reacts to produce biurea. The high temperatures then used during baking, cause biurea to transform into semicarbazide (source) (source).

However, this transformation does not necessarily make bread dangerous. Context and dose matter greatly, and are often left out of many social media reels. Let’s take a further look.

What are the health concerns surrounding Azodicarbonamide and Semicarbazide? And do these concerns translate to bread products?

It is true that ADA has been linked to respiratory issues like asthma and skin sensitisation (source), but this link is limited to inhalation exposure in occupational settings (as Phillips himself states in the video caption). Occupational exposure refers to contact that occurs in the workplace, such as factories, where the powdered form of ADA is used in large amounts.

In contrast, when ADA is used in bread it is ingested, not inhaled. Additionally, ADA use in bread is strictly regulated and only consumed in trace amounts. For example the U.S. FDA allows ADA use at a maximum of 45 mg/kg in flour (source). These amounts are far smaller than the amounts of ADA workers would encounter in a factory.

The other concern of ADA use is its breakdown product Semicarbazide (SEM). Some animal studies found SEM may cause DNA damage (genotoxicity) or weak carcinogenic effects at high doses. For example, one study in rats found SEM caused damage to DNA and RNA in some rat organs (source). However, another study in mice found no evidence of genotoxicity (source). Overall, the European Food Safety Authority has concluded that the level of SEM found in food products is not a concern to human health (source).

A note on animal studies

While animal studies are a valuable tool in scientific research and often help guide future investigations, it is important to remember that just because something is harmful to animals does not automatically mean it will be harmful to humans. For example, it is well known that chocolate can be extremely toxic to dogs (source), however this is definitely not the case for humans!

Furthermore, the doses used in animal studies are often much higher than those of typical human consumption and therefore do not translate to an accurate picture of risk in the context of a human diet.

Claim 2: “The EU banned it [ADA] in both food and food contact materials due to the carcinogenic risk [...] but here in the U.S., it’s still in some baked goods.”

Fact-check: This claim lacks context. As we’ve already noted, EU authorities published a revised evaluation on the issue of carcinogenicity. Besides, different countries follow different principles to guide safety regulations. As a result, just because an ingredient is banned in a country does not mean it is necessarily unsafe in all contexts and at any dose.

Regulatory landscape: why Is Azodicarbonamide banned in some countries and not others?

It is true that ADA has been banned in the EU, Australia, and Singapore, but it is still permitted in the U.S., Canada, and parts of Asia, within strict limits (source).

These differences often come down to risk assessment approaches. The bans of ADA in the EU reflect a precautionary approach, but this does not inherently mean that the food is dangerous and should be banned everywhere. There are equally lots of ingredients that are banned in the US but not in the EU.

For more information why not check out another recent fact check that covers the US ban of Red 3 and takes a deeper look at these different approaches.

Another great source of information on such topics is foodsciencebabe’s social media accounts, where she regularly posts videos to detail why such claims are misleading. She also provides insightful tips to recognise misleading claims. For example, if a post claims a ‘link to cancer’, always check that the author goes on to specify at what dose, and whether those links were found in humans. Here’s a video where she explains why the “this has been banned in the EU” argument can be a red flag that the claim in question is misleading:

Evaluating online claims that a food or ingredient has been linked to cancer

The presence of logical fallacies can be a reliable way to spot nutrition or health related misinformation, which differs from ‘fake news’, in the sense that it is often based on partial truths (source).

While the information given by Phillips’ is technically accurate, the way it’s presented is what makes it misleading. His video doesn’t give the whole picture and his arguments rely on the following fallacies:

- Cherry picking the data, citing articles that go along with his narrative but not providing new data that showed that previous concerns were seemingly unfounded.

- Appeal to fear: A lot of online claims reject the idea that they are fear mongering, on account that they provide a simple solution (in this case, simply read the labels and avoid such products). However, such claims can easily lead to toxic food thinking by repeatedly conveying the idea that there are hidden toxic chemicals in everyday foods, which might have been poisoning you without your knowing. They use emotionally charged language like “toxic” or “linked to cancer” without necessary context or evidence to back up such claims, and often resort to scary visuals and/or music. By appealing to fear, perceptions of risk are often affected, along with scientific literacy.

- Appeal to nature: These claims appeal to the idea that only natural is good and therefore anything “chemical” or synthetic is inherently dangerous. But this logic is flawed and demonstrates a lack of understanding of what chemicals are. Just because something is natural does not make it inherently better.

- False equivalence: Comparing two things which are not comparable in a meaningful or relevant way can easily cause misunderstandings. The logic here is flawed, because many ingredients have purposes outside of food production. For example, baking soda is regularly used in cleaning and cooking. It would be very easy to make baking soda sound unsafe to eat by comparing it with bleach, perhaps by stating that baking soda is more effective than bleach to remove some stains, and concluding that it must therefore be a powerful agent that we should not consume. But this is another false equivalence, and a flawed way to answer the question: is baking soda safe to eat?

Evaluating evidence cited to support a claim

It is also important to be able to evaluate whether a study cited is a reliable and/or relevant source to support a given claim. Phillips only gives two sources to support his argument that ADA should be avoided. The first source is an article from the Guardian. Unlike a first hand scientific paper, second hand data can sometimes be more prone to bias and occasionally misrepresent the science. This particular article cites sources like 'the food babe' and EWG, both of whom have been widely discredited due to misinformation spreading and fear mongering (source) (source).

Phillips’ second reference is a scientific paper of which he highlights the words ‘carcinogenic semicarbazide’ from the title. However, no explanation or context of the study is given, which can be a red flag.

With a deeper look at the paper in question we quickly see that it is not the strongest evidence for the argument he is making. This study examined the effects of SEM on DNA fragments in test tubes, not on live animals or humans. Additionally, while this study did observe DNA damage caused by SEM, it did not demonstrate actual cancer development; other processes may take place in living organisms that are not taking place in a test tube on a single DNA fragment. So while this study may give some mechanistic insight, it alone is not strong evidence to support the claim that ADA is dangerous in bread.

The current science and regulatory assessments on ADA suggest that consuming it in trace amounts is safe.

Final take away

While Phillips’ video raises concerns that are rooted in partial truths, it ultimately lacks the full scientific context necessary to assess real-world risk. Yes, Azodicarbonamide (ADA) can break down into semicarbazide (SEM) during baking, and yes, ADA has been banned in some countries. However, these facts alone do not prove that ADA is harmful in the trace amounts found in bread.

Scientific research and global regulatory assessments conclude that ADA is safe to consume at current permitted levels. Meanwhile Phillips’ cited evidence is drawn from few low-quality and secondary sources.

Misinformation such as this can lead to unnecessary fear around everyday foods like bread, which can be an important part of a balanced diet. For those who remain concerned, ADA-free products are available and clearly labeled. But for most people, there is no evidence-based reason to avoid ADA in bread.

By asking simple questions like ‘in what context does this food/ingredient cause harm?’, we can fill in the gaps that are often not present in social media posts warning against the dangers of everyday foods, and get a better understanding of actual risks.

@foodsciencebabe This is a logical fallacy land mine 🙄 #factsnotfear #breadtok #potassiumbromate #azodicarbonamide #foodscience #foodmyth ♬ original sound - Food Science Babe

We have contacted Warren Phillips and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Reliable claims about toxic ingredients should be backed by scientific studies or data, and provide context. Be cautious of sensational or emotional language that is often indicative of misleading content.

In a recent Instagram post, wellness influencer Warren Phillips (better known as nontoxicdad) claims of a ‘toxic yoga mat chemical’ being used to ‘fluff up’ our bread. He warns that the chemical in question, Azodicarbonamide (ADA), is so dangerous that it has been banned by the EU, and suggests that it should also be removed from U.S products as well.

But what is ADA, and is it truly harmful? Let’s break down the facts.

Full Claim: “Did you know that bread like this has a yoga mat chemical in it to fluff it up just like a yoga mat? So why is this chemical so toxic that the EU actually banned it? It's called Azodicarbonamide and when you heat it up in the baking process it can turn into semicarbazide which is a potential carcinogen. We need to share this video and let the FDA, Arby’s, and other people that are using this yoga mat chemical in our bread that it needs to come out now.”

ADA is used in bread as a dough conditioner and does break down during baking, but this does not make it dangerous at typical consumption levels. Regulatory bodies like the FDA and EFSA agree that ADA poses no health risk when used within approved limits. The video doesn't mention more recent studies which found there was no concern for human health.

Videos like this one can spread fear and misinformation about everyday foods, leading to unnecessary worry and dietary confusion. Understanding how food safety is assessed, and why dose and context matter, helps consumers make more informed choices based on evidence, not fear.

Paul Saladino’s anti-folic acid advice for pregnant women is not just wrong—it could be dangerous

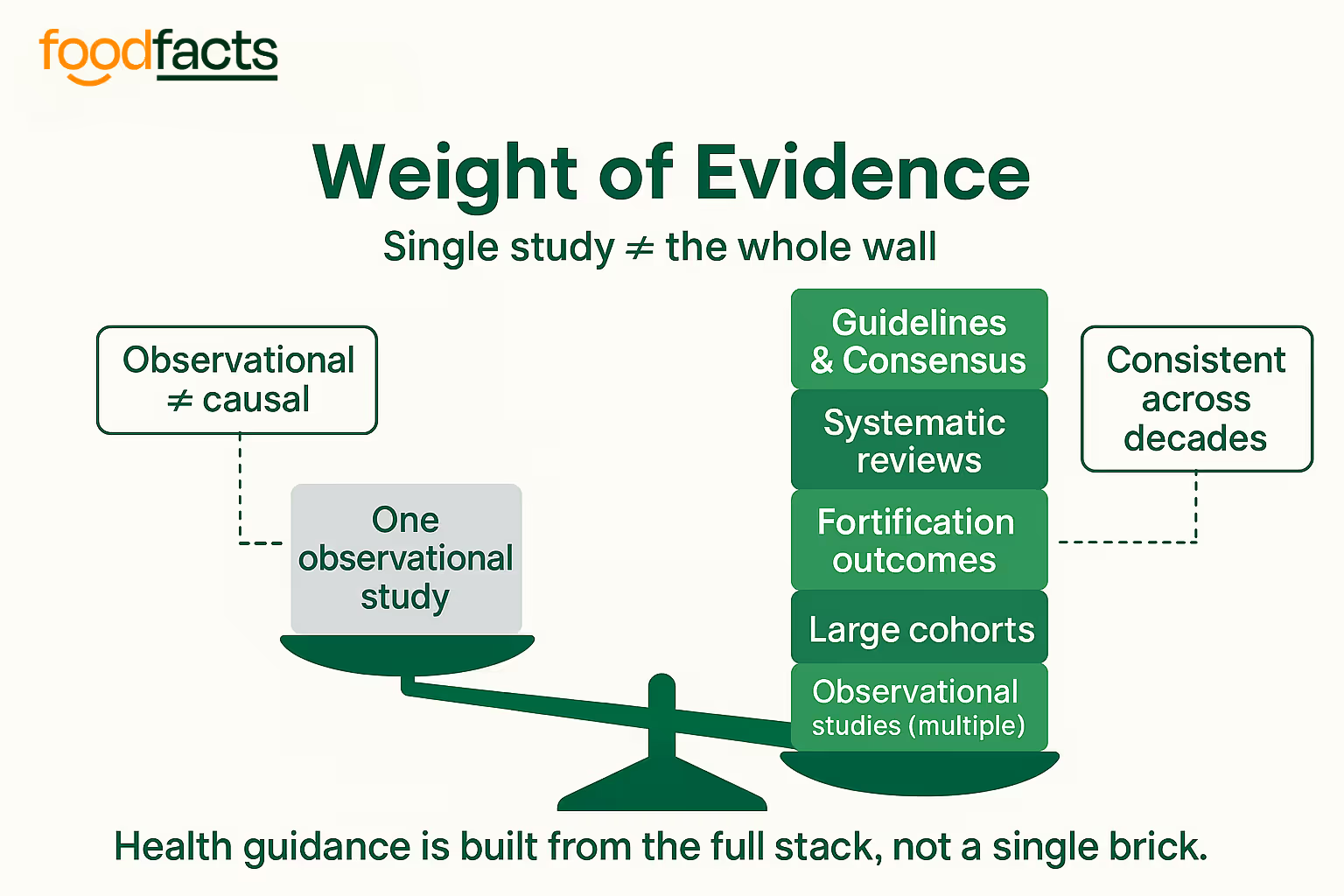

When we encounter claims on social media that something in our food could be dangerous, based on a single cited study, it is crucial to pause and ask the right questions. This step is especially important as unverified claims can cause unnecessary anxiety among vulnerable groups like parents or pregnant women. One such question is: does the cited study actually answer the question asked by the influencer? And what does the rest of the evidence say?

These are important questions, because confidence in scientific research works like building blocks. Every study might be seen as a building block, and one will inform others by prompting new questions. Gradually, the picture builds up, and so does confidence in conclusions.

Saladino supports his argument by looking solely at one study, which does not directly address the question he’s asking.

More importantly, the video omits to mention all of the existing data on folic acid, its safety and benefits which include averting around 1000 NTD-affected pregnancies annually. By contrast, evidence-based recommendations take into account the totality of the evidence available. If a study points to slightly different results, it is not ignored; rather it prompts further exploration and questioning (such as: does this study overturn prior evidence?), and updated recommendations.

You can watch the entire video in which Dr. Idz continues to provide evidence (the other ‘building blocks’ that Saladino does not mention) looking specifically at associations between folic acid supplementation during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorders, and finding the exact opposite of what Saladino is claiming. Namely that folic acid is “not only effective at preventing neural tube defects both in supplements and in food, but it also leads to a lower risk of autism spectrum disorders” (Dr. Idz).

A few red flags to keep in mind

The claims presented in Saladino’s video exhibit a couple of red flags which can be indicative of misinformation. We summarise them below:

- ‘What you think is healthy is actually harmful’ claims merit source-checking.

This common framing is not misleading in itself. However when it is regularly reinforced, it can be a red flag. Yes, misleading marketing can get people to think they are making healthy choices when they are not. However, the success of folic acid supplementation is not the result of a marketing stunt. As we’ve seen, it follows from evidence-based recommendations.

- ‘Natural vs synthetic’ framing doesn’t answer whether a food or ingredient is safe.

The decisive question is clinical outcomes. For preventing NTDs, folic acid (a synthetic form) has population‑level proof; L‑5‑MTHF currently does not show superior outcomes.

Final take away

Do not stop a standard prenatal because of social‑media claims. When in doubt, discuss your specific situation with your clinician.

We invited Dr. Saladino to comment on August 13 and will update here with any response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Dr. Federica Amati concludes that while “5‑MTHF provides equivalent folate repletion at equimolar doses,” “superiority has not been established for maternal–fetal outcomes.” That matters because recommendations are based on the totality of benefits and risks, which strongly favour continuing folic acid for NTD prevention.

Generalising from isolated studies can sidestep core principles of scientific literacy; the rest of this fact-check provides the wider context.

Claim 2: A study “found that higher levels of unmetabolized folic acid, a synthetic form of folate found in most prenatal vitamins in umbilical cord blood in Black children was associated with a significantly higher rate of autism spectrum disorders.”

Fact-check: The single study mentioned (from the Boston Birth Cohort) is observational and does not test whether taking standard prenatal folic acid is unsafe. It did find an association between higher concentrations of cord blood unmetabolized folic acid (UMFA) and a greater risk of ASD in Black children. However, as this is an observational study, with a relatively small sample size, it is not sufficient to draw these conclusions. It does not support the claim that folic acid supplementation should be avoided.

In a recent video, Dr. Idz details the reasons why Saladino’s cited study does not support his claims:

Claim 1: “Get rid of folic acid in your diet and only consume foods that have added folate as L5 methylfolate, that is the natural form of folate. Folic acid and unmetabolized folic acid are potentially very harmful for humans and for babies.”

Fact-check: The implications of this claim conflict with guidelines that have been shown to prevent serious birth defects for decades.

For more information on what exactly folic acid or folate is, you can read our other fact-check on similar claims. Here we focus on the implications of this claim in the specific context of pregnancy and babies’ health.

What the science says about folic acid fortification and supplementation

Folic acid supplementation before and during pregnancy helps to prevent serious, sometimes fatal birth defects. Multiple randomized trials and large population programmes highlight the benefits of folic acid to prevent Neural Tube Defects (NTDs) in babies (source, source).

The prevalence of babies born with NTDs reduced substantially after mandatory fortification of enriched cereal grain products began in the United States in 1998. “Fortification was estimated to avert approximately 1,000 NTD-affected pregnancies annually” according to the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report from the CDC (source). A systematic review also found that flour fortification with folic acid had a major impact on the incidence of NTDs in all of the countries where it was reported.

Scientific reviews continue to assess the latest evidence to update recommendations, concluding on the benefits of folic acid supplementation for preventing NTDs.

Looking specifically at prenatal supplementation guidelines, Dr. Federica Amati explains the reasoning behind established recommendations and why they endorse folic acid, not methylfolate, which Saladino claims is superior:

The best available evidence does not show that methylfolate (5‑MTHF) is superior to folic acid for clinically important pregnancy outcomes. Small randomized trials in pregnancy demonstrate that 5-MTHF achieves similar folate levels in the mother’s bloodstream and in her red blood cells as folic acid, while producing lower circulating unmetabolized folic acid.

The clinical relevance of lowering unmetabolized folic acid is uncertain. No trial has demonstrated better prevention of neural tube defects (NTDs) or other perinatal outcomes with 5‑MTHF over folic acid, and reviews highlight the absence of such outcome data.

Current guideline recommendations therefore continue to endorse folic acid, not methylfolate, for NTD prevention. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends a daily supplement containing 0.4–0.8 mg folic acid for all who could become pregnant, beginning at least one month preconception through the first 2–3 months of pregnancy. These recommendations are based on randomized and observational evidence showing folic acid reduces NTD risk; comparable NTD-prevention data for 5‑MTHF are lacking.

“This [study] wasn't even testing the effect of folic acid supplementation, it was looking at unmetabolised folic acid in umbilical cord blood, a completely different metric to assess which is not even proven to increase a risk of autism in the first place.

Also [the researchers] didn't even test the amount of unmetabolised folic acid in the mother's circulation, so you can't attribute the unmetabolised folic acid in the cord to the mother. And not to mention the Boston Birth cohort had a high number of pre-term births, which is a consistent risk factor for autism spectrum disorders” (Dr. Idz on Instagram on August 12, 2025).

Cross-check facts: Compare the information with multiple trusted sources to confirm accuracy.

Dr. Paul Saladino recently advised against using folic acid in prenatal vitamins, preferring ‘natural’ L-5-methylfolate, citing a Boston Birth Cohort paper on cord unmetabolized folic acid (UMFA) and autism risk. We compared that advice with current guidelines and the broader evidence, and consulted experts to bring you a reality check.

The most robust evidence and clinical guidelines worldwide recommend 400 µg of folic acid daily before conception and through early pregnancy to prevent NTDs. The study Saladino cites does not show that standard prenatal folic acid causes autism, nor does it justify abandoning folic‑acid–containing prenatals.

Influencers with large platforms can shape health behaviour. When they discourage long-standing, well established and robust guidelines (like folic acid supplementation) without strong data, they risk real‑world harm: fewer people following proven guidance, and more anxiety around ordinary foods and standard prenatals. Public figures should be accountable for claims that contradict established guidance. This article supports readers to confidently fact-check nutrition and health claims, to make decisions based on understanding, not fear.

Latest fact-checks, guides & opinion pieces

.svg)