“Not real food”? Says Eddie Abbew. A closer look at claims about tempeh, soy, and men’s health.

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

Influencer Eddie Abbew recently posted a video on social media in which he suggests that tempeh isn’t “real” food. He claims that soya is not the best source of protein, and that it has been known to increase oestrogen levels and lower testosterone, especially in men.

Keep reading to find out if those concerns are supported by evidence.

Full Claim: “I don’t understand why anyone would stop eating nature made protein like meat, poultry, fish, eggs, to eat this nonsense. Personally, I don’t believe tempeh is food. Soya beans are not the best source of protein - it doesn’t matter what claims they make on the product. You are not getting the nutrients that you think you’re getting from the protein in this product. Soya has been known to raise oestrogen levels and lowers testosterone in men especially. If you want to increase testosterone as a man, eat eggs especially and, if you want to improve your health in general then avoid tempeh because that’s not food in my opinion.”

Eddie Abbew’s statements dismiss the nutritional value of soy-based foods like tempeh, mischaracterise soy’s impact on hormones, and promote an overly narrow definition of what constitutes “real” food. Research shows that soy is a high-quality protein source. It is nutritionally complete, widely accessible, and beneficial to health. Including tempeh in your diet supports both nutrient adequacy and long-term wellbeing, especially when part of a varied, balanced eating pattern.

Even when clearly framed as opinion, nutrition advice shared with over 4 million followers carries weight. When those views discourage foods like plant proteins, despite strong evidence of their health benefits, it’s important to offer clarity and context.

Always fact-check nutrition advice that categorises food as either real or fake, with no middle ground. Such oversimplifications often miss the big picture of what constitutes a well-balanced diet.

Claim 1: “Soya beans are not the best source of protein [...] You are not getting the nutrients that you think you’re getting from the protein in [tempeh].”

Fact-Check: Soy is a high-quality source of protein.

This claim is misleading because of its framing: ranking protein sources in isolation oversimplifies nutrition and can lead to unnecessary restrictions.

How is protein quality assessed?

Scientists evaluate protein based on two key factors: whether it contains all nine essential amino acids, and how easily our bodies digest and absorb them. Tools like PDCAAS (Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score) and the newer DIAAS (Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score) score proteins on these criteria (source, source). A higher score indicates a protein that’s more useful to the body.

Soy protein performs well by both measures.

It’s one of the few plant proteins that’s considered “complete,” and it scores highly on both PDCAAS and DIAAS (source). This means soy delivers all the amino acids your body needs to build and repair tissues. In other words, you are getting quality protein when you eat soy, whether it’s in the form of tofu, tempeh, or edamame.

Should we rank protein sources?

It all depends on context. Understanding protein quality is essential to inform nutritional guidelines, and it helps consumers to make informed decisions.

But on social media, rankings are often used to promote restrictive diets, based on the argument that the foods that score lower in one area are not worth eating. This can be problematic because it fuels misunderstanding about how nutrition works and can lead to unnecessary restrictions.

Health isn’t about consuming the “highest scoring” protein in isolation, it’s about the overall pattern of what you eat. Some of the healthiest dietary patterns (for example the Mediterranean Diet) include a variety of protein sources, plant and animal, making them accessible to all through a focus on balance and variety. A better approach is to embrace variety, consider context (e.g., allergies, preferences, accessibility, environmental impact), and aim for adequate protein intake overall.

As research consistently points to associations between higher intake of plant protein and lower risk of all-cause mortality, the suggestion that we should exclude plant sources of protein contradicts scientific evidence and could negatively affect health.

Claim 2: “Soya has been known to raise oestrogen levels and lowers testosterone in men especially.”

Fact-Check: This claim is not supported by evidence.

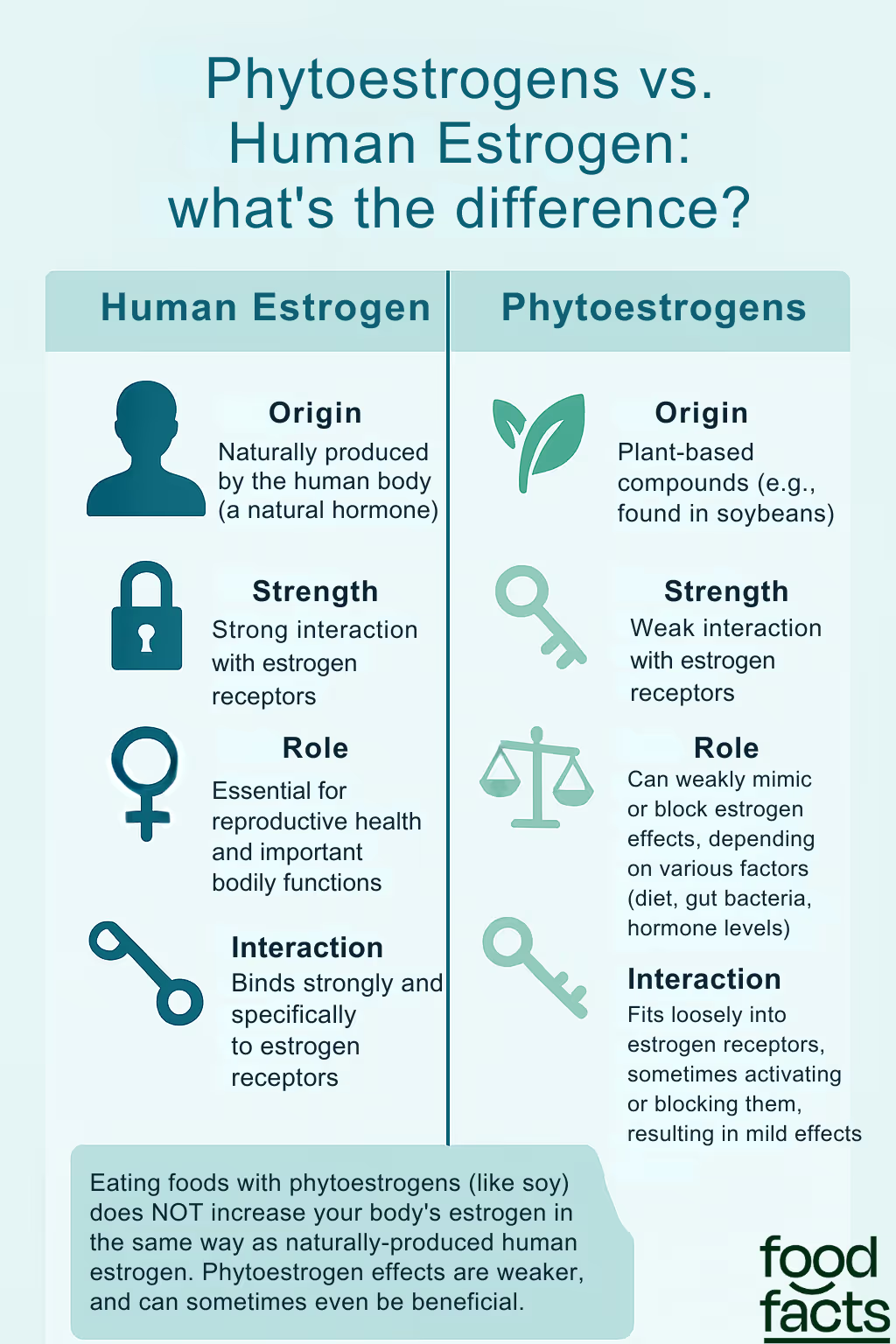

Phytoestrogens vs. human estrogen: where the confusion starts

Phytoestrogens, like those found in soy, are often confused with human estrogen, but they are quite different. Human estrogen is a hormone naturally produced by the body that plays a key role in reproductive health and other functions. Phytoestrogens, on the other hand, are plant compounds that only look a bit like estrogen and can weakly interact with the body’s estrogen receptors (source). Because they are much weaker than human estrogen, phytoestrogens can sometimes mimic its effects, but they can also block estrogen’s action depending on the situation. The way phytoestrogens work in the body is complex and depends on factors like how much is eaten, a person’s gut bacteria, and their own hormone levels (source).

Importantly, eating foods with phytoestrogens, such as soy, does not mean the body’s estrogen levels will rise in the same way as if it produced more of its own hormone. In fact, the effects of phytoestrogens are generally much milder and can even be beneficial for some health conditions according to this 2024 study.

So, while phytoestrogens and human estrogen can both interact with the same receptors, they are not the same and do not have the same strength or effects in the body.

The actual effects of soy on male hormones

The claim that soy raises estrogen (oestrogen) levels and lowers testosterone in men is not supported by the best available clinical evidence. Where do these claims then come from?

Some small or short-term studies have reported minor reductions in testosterone or changes in other hormone levels, but these effects are generally modest, inconsistent, and not linked to clinically meaningful outcomes (source).

Large, high-quality meta-analyses of human studies have found that neither soy foods nor soy isoflavone supplements significantly affect testosterone, free testosterone, estradiol (a form of estrogen), or other key sex hormones in men, regardless of dose or duration of intake according to this 2020 meta-analysis. These findings have been confirmed again and again in research. Even men who eat a lot of soy—far more than most people do—show no signs of hormonal changes or "feminising" effects.

Animal studies and the phenomenon of ‘cherry picking’

Many of the concerns and claims about soy and hormones come from animal studies, especially those done on rats and mice. In these studies, the animals were often given very high doses of soy compounds - much more than a person would ever get from eating tofu, soy milk, or other soy-based foods like tempeh (source). As a result, outcomes observed in animals, such as modest oestrogen‑like activity, do not reliably translate to effects in humans.

Overall, the consensus from robust human research is that soy consumption does not feminise men or disrupt their reproductive hormones.Influencers on social mediasuch as Eddie Abbew frequently rely on selective citation—also known as cherry‑picking—where only studies fitting a particular narrative are highlighted, while the broader, more rigorous evidence is ignored. For example, a 2007 small-scale trial observed a minor decrease in testosterone among 12 men consuming 56 g per day of isolated soy protein (for 4 weeks), but this dose far exceeds typical diets and the effect was neither consistent nor sustained (in a sample of only 12 individuals). However, that single finding has been disproportionately cited, even though larger and better-quality studies have found no real effect.

Claim 3: “I don’t believe tempeh is food.” “If you want to improve your health in general then avoid tempeh because that’s not food in my opinion.”

Fact-Check: This claim misrepresents both nutrition science and cultural food traditions. While it is framed as a personal opinion, it reflects a broader misunderstanding of how foods are classified, and how dietary diversity supports health.

What is “real” food?

A lot of Eddie’s content revolves around the idea of “real” food, and his criticism of the food system which pushes items that, in his view, are disguised as food but do not support optimal health. This is based on valid concerns around the prevalence of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) in our diet, which indeed dominate supermarket shelves (source). But tempeh isn’t one of them.

Foods are commonly categorised using the NOVA classification system, which groups foods by their level of processing: from unprocessed or minimally processed (Group 1), to ultra-processed foods (Group 4), which tend to be energy-dense, nutrient-poor, and heavily altered through industrial processing.

It might seem, at first, that when Eddie Abbew refers to “real” food, he means foods that are unprocessed or minimally processed. But when you look more closely at his content, the definition appears much narrower, limited to a handful of primarily animal-based, whole foods.

That’s where the problem lies: this framework promotes an overly restrictive eating pattern that labels many health-promoting foods as unacceptable.

Tempeh is very much food: nutritionally, culturally, and historically.

Tempeh has only started to gain popularity in the UK in recent years, and therefore might still be unfamiliar to some. But it has been a staple in Indonesian cuisine for centuries.

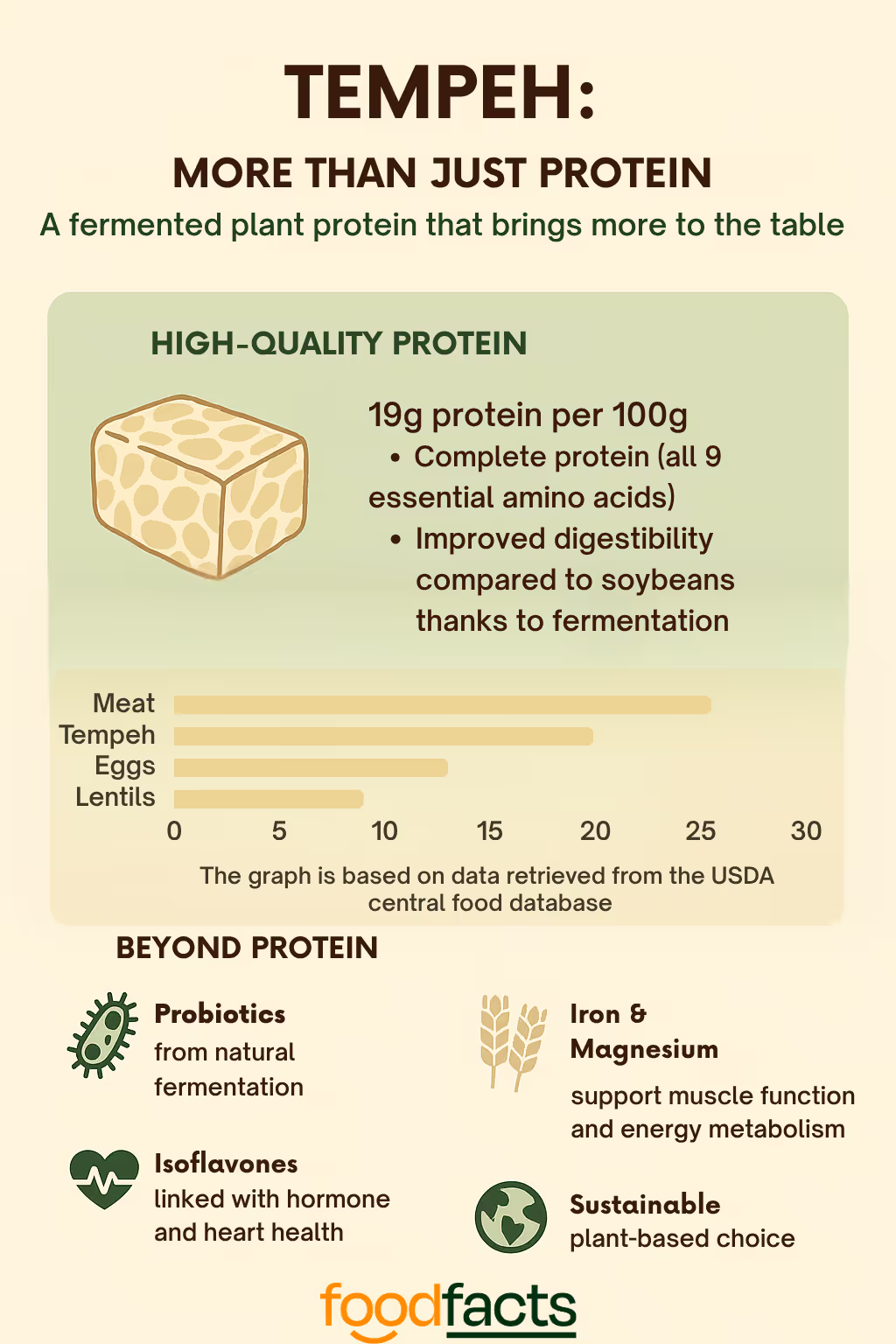

Tempeh is made by fermenting cooked soybeans with a natural starter culture. This fermentation process not only preserves the soybeans but also enhances their nutritional value and digestibility, increasing protein availability, reducing antinutrients, and introducing gut-friendly compounds like probiotics (source).

It offers a great example of beneficial processing, in this case, fermentation, that improves both nutrient bioavailability and gut health (source). Indeed part of the issue with Eddie’s narrow categorisation of “real” food is that it also fuels distrust in any form of food processing, ignoring its benefits to make food safe (like pasteurisation), or to enhance nutrition.

Tempeh’s place in a balanced diet

Rather than thinking of foods as “good” or “bad,” it’s more helpful to view them as part of a diverse nutritional toolbox. Tempeh offers:

- High-quality protein (about 19g per 100g);

- Fibre, iron, magnesium, and other micronutrients;

- Probiotics from natural fermentation;

- Isoflavones that may benefit heart and hormonal health;

- A low-saturated-fat alternative to processed meat.

The purpose of tempeh is not to replace all animal-protein. But it can be an excellent option for people who wish to reduce meat consumption, for those concerned about managing cholesterol or cardiovascular health, and for anyone seeking more fibre and gut-friendly diversity.

Final Take Away

While it’s important to question food marketing and make informed choices, much of what circulates online fuels unnecessary fear around certain foods or ingredients. Often, foods are demonised not because of evidence, but because they don’t align with the dietary views promoted by some content creators.

And this matters. It’s not just a question of scientific accuracy: it has real implications for public health. Research consistently shows that increasing plant protein in the diet is associated with a lower risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and all-cause mortality. At the same time, many people in the UK and other countries fall well below recommended fibre intake.

Tempeh is a minimally processed food that supports dietary diversity, and a great way to increase intake of both plant protein and fibre. Discouraging its consumption not only misrepresents nutrition science, it also undermines public health efforts to promote access to affordable, nutrient-dense foods that support long-term health.

We have contacted Eddie Abbew and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

📚 Sources, resources + further reading

Schaafsma, G. (2000). “The Protein Digestibility–Corrected Amino Acid Score.”

Moughan, P.J. & Lim, W.X.J. (2024). “Digestible indispensable amino acid score (DIAAS): 10 years on.”

Hertzler, S.R. et al. (2020). “Plant Proteins: Assessing Their Nutritional Quality and Effects on Health and Physical Function.”

Naghshi, S. et al. (2020). “Dietary intake of total, animal, and plant proteins and risk of all cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies.”

Ceccarelli, I. et al. (2021) “Estrogens and phytoestrogens in body functions.”

Chavda, V. et al. (2024) “Phytoestrogens: Chemistry, potential health benefits, and their medicinal importance.”

El-Latif, N. et al. (2024) “Impact of Soy Protein Isolate Supplementation on Testosterone Hormone Levels and Its Biosynthesis Pathway in Male Rats.”

Gardner-Thorpe, D. et al. (2003) “Dietary supplements of soya flour lower serum testosterone concentrations and improve markers of oxidative stress in men.”

Goodin, S. et al. (2007) “Clinical and biological activity of soy protein powder supplementation in healthy male volunteers.”

Patisaul, H., & Jefferson, W. (2010) “The pros and cons of phytoestrogens.”

Reed, K. et al. (2020) “Neither soy nor isoflavone intake affects male reproductive hormones: An expanded and updated meta-analysis of clinical studies.”

Rauber, F. et al. (2019). “Ultra-processed foods and excessive free sugar intake in the UK: a nationally representative cross-sectional study.”

Monteiro, C.A. et al. (2019). “Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them.”

Wu, J.Y. (2025). “Unraveling the impact of tempeh fermentation on protein nutrients: An in vitro proteomics and peptidomics approach.”

Rizzo, G. (2024). “Soy-Based Tempeh as a Functional Food: Evidence for Human Health and Future Perspective.”

Song, M. et al. (2016). “Association of Animal and Plant Protein Intake With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality.”

Xu, M. et al. (2025). “Dietary protein and risk of type 2 diabetes: findings from a registry-based cohort study and a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies.”

Zheng, J. et al. (2020). “The Isocaloric Substitution of Plant-Based and Animal-Based Protein in Relation to Aging-Related Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review.”

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)