Should you throw out all your plastic containers? A fact-check on microplastics and kitchen safety

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

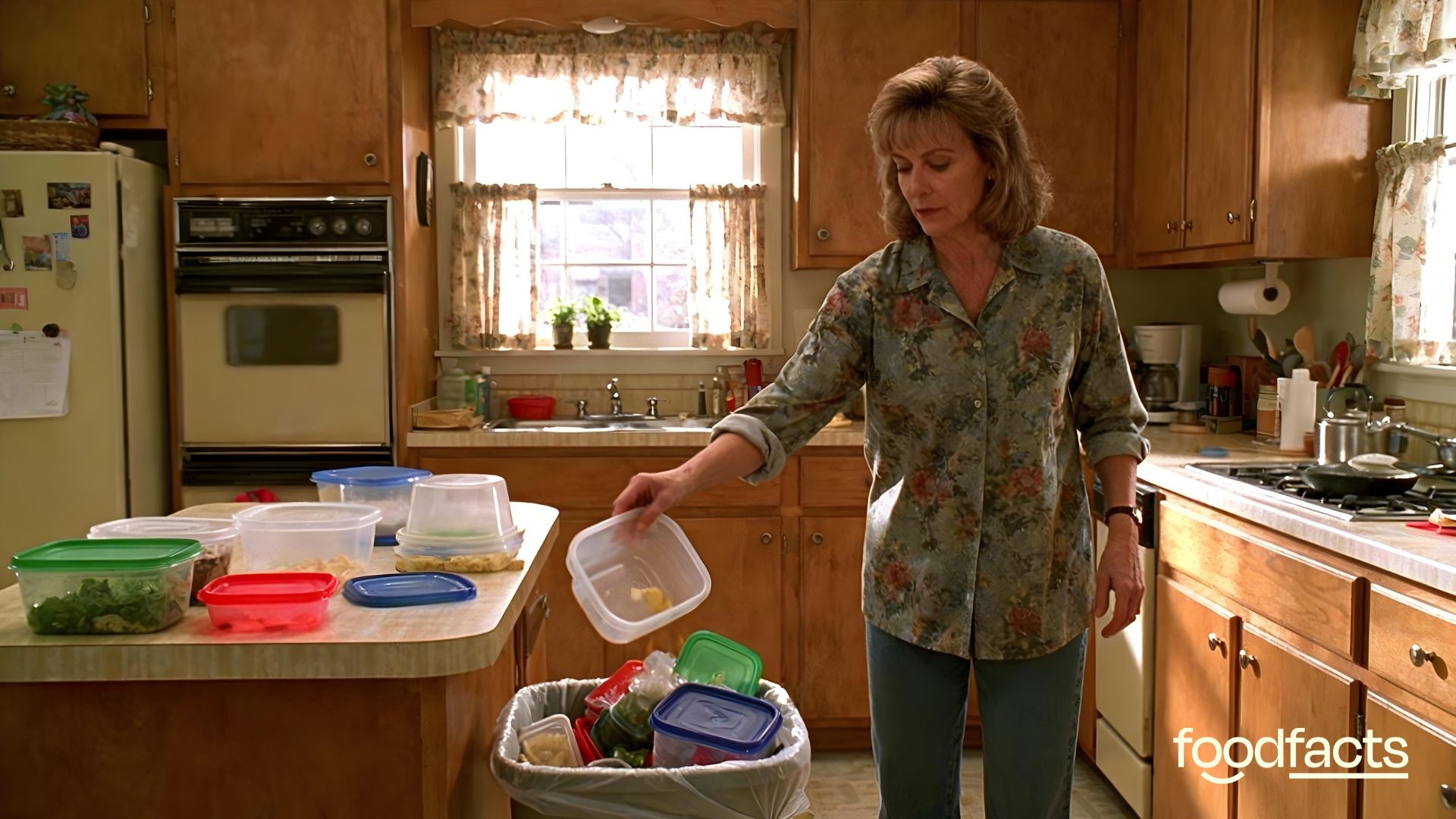

On 15th March 2025, Warren Phillips, known as “non-toxic dad” on social media platforms, posted a video in which he claims we should get rid of all plastic tupperware containers because of microplastics leaching into food.

Full Claim: If you have a plastic one (strainer) and you’re pouring hot water and food, those microplastics and other toxins can absorb into your food. ….. Get rid of all that plastic tupperware type containers that just degrade and fall apart and release those toxins into your food. Get a set of glass storage containers… Most importantly, they don’t contaminate your food. (15th March 2025)

Heat and repeated use can cause some plastics to leach chemicals or release microplastics, but this risk varies depending on plastic type, condition, and temperature. Replacing worn or low-quality plastic containers can help reduce this risk. Glass storage is safer overall but often still includes plastic lids or seals. Shifting to non-plastic materials like glass is a reasonable precaution, and regular inspection of kitchen items for wear can further reduce exposure.

This is one of many similar claims making social media and news headlines. Claims like this can be panic-inducing, especially given its consumption links to negative health outcomes including some cancers, respiratory disorders, and irritable bowel syndrome. But before you throw out all your plastic kitchen equipment, it is worth understanding the science behind the claims, this could save your immediate bank balance.

Context Matters: A study might sound compelling in isolation, but check if it aligns with broader research on the topic.

Claim 1: “You’re pouring hot water and food, those microplastics and other toxins can absorb into your food” (from a strainer)

Fact-Check: Plastic utensils—including strainers—can release microplastics when exposed to heat, scratching, or prolonged use. Common materials like polypropylene (PP) and nylon can wear down over time, especially when repeatedly exposed to heat.

That said, brief contact with boiling water (like draining pasta) doesn’t likely cause a meaningful release of microplastics unless the item is already damaged or degraded. Lab tests that show plastic shedding from boiling involve sustained high temperatures for 15 minutes or more, which doesn’t reflect normal kitchen use. Microplastic release from plastic strainers is more likely due to mechanical wear (e.g., cracks, scratches) than the occasional exposure to hot water.

Claim 2: “Get rid of all that plastic tupperware type containers that just degrade and fall apart and release those toxins into your food.”

Fact-Check: At the heart of the debate about plastic food containers—especially the ones labeled “microwave-safe”—is a growing concern about what really happens when you repeatedly heat them. Many of these containers are made from PET (polyethylene terephthalate) or PP (polypropylene), both of which are generally considered safe under typical use. But the key phrase here is “typical use”—and it turns out, the way we use these plastics can make a big difference.

Just because something is labeled “microwave-safe” doesn’t mean it’s immune to breaking down under heat. Research suggests that microplastics (MPs) and nanoplastics (NPs) can be released from plastic containers, especially during high-heat scenarios like microwave reheating. In fact, in a single 3-minute microwave session, plastic containers have been shown to release up to 4.22 million microplastic particles and over 2 billion nanoplastic particles per square centimeter. To put that in perspective, you’d need six months of room-temperature storage to produce the same level of release. Freezing tupperware containers can also increase brittleness, also increasing the likelihood of shedding microplastics.

Claim 3: “Get a set of glass storage containers […] Most importantly, they don’t contaminate your food.”

Fact-Check: Glass is non-reactive, durable, and does not leach chemicals or release particles. A recent study found no microplastic contamination from food stored or prepared in glass. However, many glass containers still use plastic lids or silicone seals, which can degrade over time. So while the glass itself is safe, it’s important to check the condition of the lids regularly.

Final Take Away

The claim that all plastic Tupperware and similar containers should be discarded due to microplastics leaching into food is grounded in a real concern. However, the risk depends on several factors, including the type of plastic - PP and PET are generally safer under typical use - condition, and use.

It is also important to consider that the impacts of microplastics in the human body are still not fully understood. While some studies suggest possible links to inflammation and endocrine disruption, long-term evidence remains limited. Microplastics have been cited in fresh and bottled drinking water, and a wide range of foods, including seafood, animal products, plant products, beverages, and salt. However, the risk of microplastics entering food during home food preparation via plastic cookware is a relatively novel area of concern, still under study. Understanding when and how plastics break down can help you make informed—and affordable—choices.

Social media is full of posts on this topic, often using alarming, absolute language that can create unnecessary panic. Instead, practical steps—such as replacing worn plastic items, avoiding heating food in plastic, and choosing glass or stainless steel when possible—can meaningfully reduce your exposure.

We have contacted Warren Phillips and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

📚Sources

BfR. (2019). “Polyamide Kitchen Utensils: Keep contact with hot food as brief as possible.”

Chen Y. et al. (2023). “Plastic bottles for chilled carbonated beverages as a source of microplastics and nanoplastics.”

Cole M., et al. (2024). “Microplastic and PTFE contamination of food from cookware.”

Deng J., et al. (2022). “Microplastics released from food containers can suppress lysosomal activity in mouse macrophages.”

Hussain K., et al. (2023). “Assessing the Release of Microplastics and Nanoplastics from Plastic Containers and Reusable Food Pouches: Implications for Human Health.”

Kadac-Czapska K.,et al. (2022). “Food and human safety: the impact of microplastics.”

Liu Y., et al. (2024). “A systematic review of microplastics emissions in kitchens: Understanding the links with diseases in daily life.”

Winiarska E., et al. (2024). “The potential impact of nano- and microplastics on human health: Understanding human health risks.”

World Health Organisation (2019). “Microplastics in drinking water.”

Zheng X., et al. (2023). “Quantification analysis of microplastics released from disposable polystyrene tableware with fluorescent polymer staining.”

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)