“I changed my diet and got pregnant”: What’s the evidence behind these claims?

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

An article published in The Sun on 25 October 2025 recounts the experience of a woman who, after several miscarriages, became pregnant with twins following a shift from a vegetarian or vegan diet to one centred on red meat and animal foods. The piece frames this change as a possible turning point in her fertility journey and suggests that a “carnivore” or high-animal-food diet played a decisive role.

This analysis does not question the woman’s personal experience. Instead, it offers a guide to reading articles like this one with a scientific lens: beyond the individual story, what evidence is presented to support the implied connection? What is left out, and how does this compare with what scientific research currently tells us about diet and fertility? The aim of this fact-check is to help readers assess how such narratives are constructed, what kinds of reasoning they invite, and where careful scrutiny is most needed.

Current scientific consensus shows that balanced, plant-rich dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet are linked to improved fertility outcomes, whereas high intakes of red and processed meat are associated with lower fertility. This is not about “carnivore versus vegan,” but about how we evaluate information. Sound evidence comes from repeated studies, transparent methods, and biological mechanisms that explain why patterns occur.

Articles like this one illustrate how selective framing can turn a single story into a persuasive but misleading narrative. Infertility concerns are profoundly sensitive and affect roughly one in six people worldwide. People experiencing repeated loss or difficulty conceiving are often searching for hope, which makes them particularly vulnerable to persuasive claims that promise control or certainty.

But when decisions are made on the basis of incomplete information, they can lead to restrictive or unbalanced diets that increase the risk of nutritional deficiencies and other health complications. This is why ensuring that health information is communicated accurately and in context is so important: it helps protect readers’ well-being and strengthens public trust in science and journalism alike.

Sensational headlines make for compelling reads. But their conclusions should be supported by data and evidence, otherwise the risk of inferring beyond individual circumstances is high.

Anecdotes gain particular influence when shared through social and popular media, where emotional resonance often outweighs scientific rigour. But without careful context, they can easily be misinterpreted. In this case, the implied message is twofold: 1) that a carnivore diet can support fertility and 2) that doctors do not tell women that diet matters. Let’s look at both claims in detail.

Claim 1: A carnivore diet can support fertility

Anecdotes alone cannot answer the question “can a carnivore diet support fertility?” because they lack the necessary context to separate cause from coincidence. In this case, we have no information about the woman’s medical history, underlying conditions, or other lifestyle changes she may have made, nor any way to know what would have happened had she not changed her diet. Without that background, it’s impossible to determine whether the outcome was linked to the diet itself, another factor, or simply chance.

Let’s examine what other evidence is used in the article to make and support this claim.

How is this claim presented in the article?

The article states that after “years avoiding meat,” the woman began eating “high-quality animal protein, eggs, butter and collagen-rich foods” and believed “the boost in nutrients and healthy fats played a key role.” She goes on to explain, “I watched a video of a doctor who recommended being on a carnivore diet to get pregnant.”

While this is presented as the turning point, the article does not name the doctor or provide any information about the existing evidence on the links between diet and fertility.

What evidence does the article provide?

The article relies on two main sources which are credited as supporting the validity of the claim:

- An unnamed doctor promoting a carnivore diet to become pregnant.

There are several doctors who promote the carnivore diet through their social media platforms. They represent a small but very visible minority among the medical community. For someone searching online for advice on using this diet to improve fertility, it is likely that they would come across the work of Dr Robert Kiltz, so it is reasonable to assume he may be the doctor being referenced in the article. Dr Robert Kiltz is a US-based obstetrician and gynaecologist who is board-certified in reproductive endocrinology. He has also written several books, in which he advocates for a “keto-carnivore diet” for fertility.

It is worth noting that in a recent video, Dr Kiltz questioned whether his own food choices could have led to recent, personal health issues (he mentions acute colitis), and concluded: “maybe my focus on only beef and carnivore is not going in the right direction.” Why does this matter? Because it highlights the importance of distinguishing between personal beliefs and peer-reviewed scientific research as a basis to guide dietary and health recommendations.

- A book: The Great Plant-Based Con by journalist Jayne Buxton, which argues that plant-based diets are harmful to health.

Again, this book is not peer-reviewed scientific work, and its conclusions contradict extensive evidence showing that well-planned plant-based diets are nutritionally adequate and associated with numerous health benefits (source).

This matters because popular media accounts can shape public understanding of what counts as “evidence.” When non-scientific materials and individual medical opinions are presented instead of peer-reviewed research, they can distort the public’s perception of scientific credibility.

The article also highlights a video by Steak and Butter Gal, a social media influencer frequently criticised by health professionals for spreading dietary misinformation and flawed reasoning which, if followed, could lead to health complications. The inclusion of this video further amplifies this one-sided narrative.

As a result, readers are left with a very skewed picture of what the science says about how diet might impact fertility – and there are a lot of studies looking precisely at those links, which the article fails to mention.

What evidence is not mentioned in the article?

The article omits decades of research examining the relationship between diet and fertility. Large-scale systematic reviews and meta-analyses published in journals such as Nutrients, Advances in Nutrition, or Biology (Basel) show that:

- Higher red and processed meat intake is linked with lower fertility rates and poorer embryo development (source, source).

- Diets rich in plant foods, fish, whole grains, and unsaturated fats, such as the Mediterranean diet, are associated with better fertility outcomes and improved metabolic and hormonal health (source, source, source).

- Including more plant-based sources of protein (such as lentils, beans and nuts) and fewer animal sources may improve fertility (source).

- Soy foods and dairy have been found to support fertility when consumed as part of balanced diets, contradicting popular hypotheses (source).

Dr Layne Norton addresses similar claims in the following video:

What about specific diets?

The keto diet shares some similarities with the carnivore diet mentioned in the article (both are high in fat and very low in carbohydrates), but unlike the carnivore diet, the keto diet typically includes a wider variety of foods, such as non-starchy vegetables, nuts, and dairy. Research surrounding keto diets and fertility is very limited. According to this review, it has mainly focused on obese and overweight women with PCOS, and the studies mentioned have a very small number of participants (27 and 12, respectively). The researchers also caution against the long-term use of this diet, “because it may also lead to deficiencies in certain important components and nutrients,” particularly during pregnancy.

This is a crucial point. It shows that while diet can indeed play a role in fertility, the issue is multifactorial. It is affected by underlying conditions, overall nutritional adequacy, and medical context. Anecdotes cannot answer the question “will this work for me?”, partly because we do not know the individual’s full health profile or whether other factors, such as PCOS, played a role. This underlines the importance of seeking guidance from qualified healthcare professionals when making dietary changes.

There is very limited data on carnivore diets themselves. Because such diets eliminate entire food groups and may pose nutritional risks, it would be ethically questionable to conduct trials particularly in populations trying to conceive.

Thus, the omission of this evidence leaves readers with the impression that a carnivore diet is a promising and potentially scientifically supported option, as it references at least one doctor who supports it. In reality, it is untested and contradicts existing data on the impact of different foods on fertility.

Bottom line

The emotional power of a personal story, combined with selective sourcing, makes the claim highly appealing.

But here’s the problem:

- It’s not about carnivore versus vegan. That framing attracts attention and clicks but oversimplifies nutrition science, which overwhelmingly supports balanced, diverse diets made up of whole foods.

- It’s an example of cherry-picking. The article only includes sources that support one side of the argument, ignoring substantial data to the contrary.

- It undermines scientific literacy. Understanding scientific evidence requires knowing how it is built. Research starts with a question. When results are reproduced and plausible biological mechanisms can explain why results occur, the evidence grows stronger.

Anecdotes, by contrast, sit at the bottom of the evidence hierarchy. They are valuable as starting points but cannot establish causation, because they don’t control for confounding factors or test biological mechanisms.

This leads us to the second implied claim and the main issue which comes from the framing of The Sun’s article: undermining trust in scientific evidence, and in health professionals.

Claim 2: Doctors don’t tell women that diet matters

How is this claim made?

The article quotes the woman saying: “Doctors say diet doesn’t matter, but I believe it still does.” Negative experiences whereby people’s concerns have been dismissed by health professionals are real, and should not be dismissed. However, by adding that “Molly decided to take matters into her own hands,” and by not considering other viewpoints, readers might be left with the impression that this is common practice.

This framing suggests that healthcare professionals dismiss nutrition as irrelevant to fertility, implying that women must rely on self-directed diet changes or social media advice instead.

The article also implicitly challenges established dietary guidelines, which consistently emphasise balance and moderation, by using the subheadline: “Molly Brown now loads up her plate with bacon and butter and credits it for making her healthier.” Later, it links to a video of a woman eating entire sticks of butter, imagery that reinforces the appeal of dietary extremes rather than the evidence-based principle of balanced nutrition.

How is this claim reinforced by omission?

By omitting information about current dietary guidelines and how they are formulated, the article misrepresents what doctors actually say. This is an example of a straw man argument: it constructs a simplified version of medical advice only to dismiss it.

In reality, public-health agencies and fertility specialists acknowledge that diet can play an important role in reproductive health. The NHS clearly advises:

“If you're trying to get pregnant, it’s important to take folic acid every day, eat a healthy diet, and avoid drinking alcohol. This will help your baby develop healthily.”

Doctors also recommend maintaining a balanced weight, monitoring vitamin D and iron levels, and avoiding restrictive diets during conception and pregnancy. By omitting this, the article risks encouraging readers to distrust professional guidance and “take matters into their own hands” in ways that could lead to nutritional deficiencies or other health risks.

Final take away: seeing the bigger picture

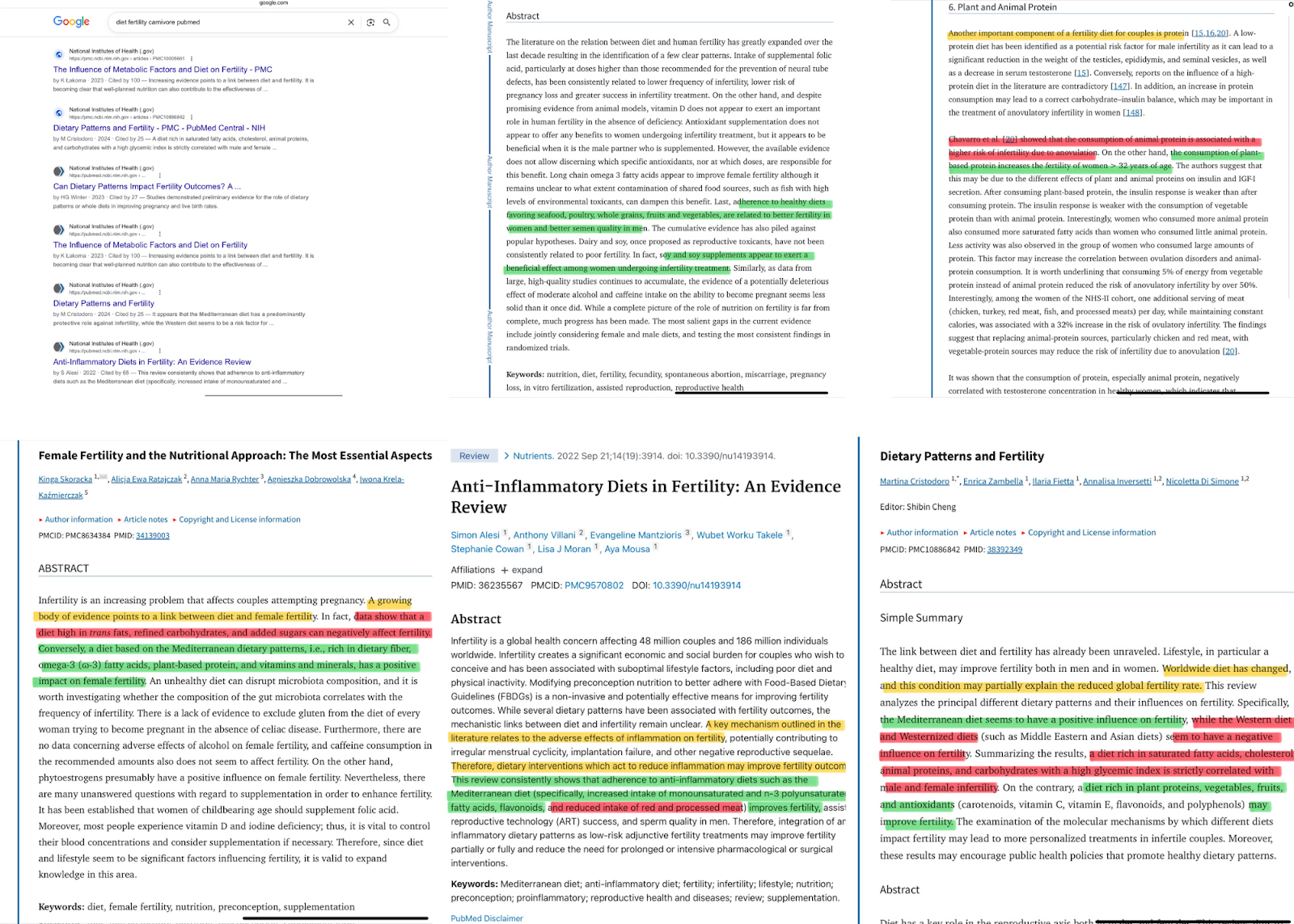

To conclude, it’s useful to visualise how social and popular media often distort the balance of available scientific evidence. A quick search for “carnivore diet fertility,” the kind of query a reader might make after encountering this story, yields several answers from Dr Kiltz and other carnivore promoters, lots of social media forums, and a single blog post challenging these popular claims.

However, simply adding the term “PubMed” to the same search produces an entirely different picture: a large number of peer-reviewed studies examining the relationship between dietary patterns and fertility. The snapshots below come from several of these papers, some of which are systematic reviews: studies that analyse and synthesise results from multiple investigations to identify consistent trends.

The aim of this visual comparison is not to present every study available, but to show how popular media can focus public attention on a narrow, highly promoted idea while overlooking the breadth and consistency of existing scientific evidence.

Social media further distorts this picture by amplifying confident voices that echo one another’s claims. A handful of personalities frequently cite each other across podcasts, blogs, and short-form videos, creating the illusion of a broad scientific consensus where there might be none. Algorithms reward repetition and emotional certainty, not accuracy or nuance.

This feedback loop obscures the substantial body of peer-reviewed evidence, and the many experts who do not share these views.

We have contacted The Sun and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources

- WHO (2023). “1 in 6 people globally affected by infertility: WHO.”

- British Dietetics Association. “Vegetarian, vegan and plant-based diet.”

- Dinu M, et al. (2017). “Vegetarian, vegan diets and multiple health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies.”

- Dr. Idz’s Instagram (2 June 2024)

- Braga DP, et al. (2015). “The impact of food intake and social habits on embryo quality and the likelihood of blastocyst formation.”

- Skoracka, K. et al. (2021). “Female Fertility and the Nutritional Approach: The Most Essential Aspects.”

- Cristodoro, M. et al. (2024). “Dietary Patterns and Fertility.”

- Alesi, S. et al. (2022). “Anti-Inflammatory Diets in Fertility: An Evidence Review.”

- Lakoma, K. et al. (2023). “The Influence of Metabolic Factors and Diet on Fertility.”

- Gaskins, A.J. & Chavarro, J.E. (2018). “Diet and fertility: a review.”

- Salvaleda-Mateu, M. et al. (2024). “Do Popular Diets Impact Fertility?”

- NHS (2023). “Trying to get pregnant.”

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)