Does yoghurt cause gut disruption?

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

Kara Swanson regularly challenges the idea that adding chia seeds and fruit to Greek yogurt supports gut health. She argues that dairy can disrupt the gut, drive inflammation, and lead to bloating, and contrasts this with high-fibre, plant-based breakfasts, which she says are what will “heal the gut,” “calm inflammation,” and “beat the bloat.”Kara Swanson challenges the idea that adding chia seeds and fruit to Greek yogurt is enough to make it a high-fibre breakfast. She argues that this is because dairy can disrupt the gut, drive inflammation, and lead to bloating, and contrasts this with high-fibre, plant-based breakfasts, which she says are what will “heal the gut,” “calm inflammation,” and “beat the bloat.”

In this fact check, we examine the evidence behind these claims about dairy, assessing whether dairy and fibre really need to be opposed.

There is no scientific basis for advising against yoghurt as a driver of inflammation. Combining yoghurt with chia seeds is common in research and product development, plays nicely with probiotic cultures, and offers a practical way to add protein, fibre, and plant omega-3s to a snack.

Food rules spread fast, fear even faster. When we label common pairings as harmful without context, people miss out on straightforward ways to eat well.

Look for evidence: Reliable claims should be backed by scientific studies or data.

Chia seeds and yoghurt are a common combination which many people enjoy for breakfast. We have contacted Kara Swanson, who clarified that the main point of her post was not to say that the combination causes gut issues, but rather to emphasise that adding chia seeds and fruit to yoghurt doesn’t make it a high-fibre breakfast. While it seems that the issue presented rests with the impact of dairy, no further evidence was provided to support the suggestion that dairy can cause gut disruption.

Let’s start by checking the research on dairy and inflammation.

Claim 1: Dairy can disrupt the gut and raise inflammation

Fact-check: Does dairy “disrupt the gut” or drive inflammation? The short answer is no in most people.

“Dairy disrupts the gut” sounds persuasive because it plugs into two real things. First, inflammation is a very broad term. It can mean acute immune responses, low grade metabolic inflammation, gut barrier issues, skin flares, even joint pain. Second, lots of people experience digestive discomfort. So when a content creator links those two and points to one food group, it can feel true even if the science is thin.

That is exactly why broad claims need to be backed by scientific evidence. If someone implies dairy is inflammatory for everyone, we should check at least three things:

What population was studied? Many people with lactose intolerance or milk protein allergy do react, and that is valid. But that data cannot be stretched to the general population.

What kind of study was it? Randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses on dairy and inflammatory markers often show neutral or slightly anti-inflammatory results in healthy adults and people who are overweight. That is stronger evidence than an anecdote or a single in vitro paper.

Are we talking about the actual food people eat? A fermented yoghurt with live cultures, modest sugar and some fibre on the side behaves differently in the gut than a sweetened milk drink.

For example, clinical reviews (source, source) on dairy and inflammation in adults report no pro-inflammatory effect of usual dairy intake, and in some cases improved markers in people with metabolic risk. That is relevant because it studies humans eating normal dairy, and measures real biomarkers. Studies on fermented dairy (source, source) are useful because they show that adding live cultures does not damage gut health and can support microbial diversity. Work on lactose intolerance (source) is important too, but it tells a narrower story, namely that undigested lactose can cause symptoms which is a tolerance issue, not proof that dairy universally disrupts the gut.

More broadly speaking, if a post cites “a study” without telling you who was studied, how long the study ran, what was measured, or whether the product looked like the yoghurt in your fridge, it is not enough to make broad recommendations to the public.

Claim 2 (implied): Adding chia seeds to yoghurt isn’t enough to make it a supportive breakfast.

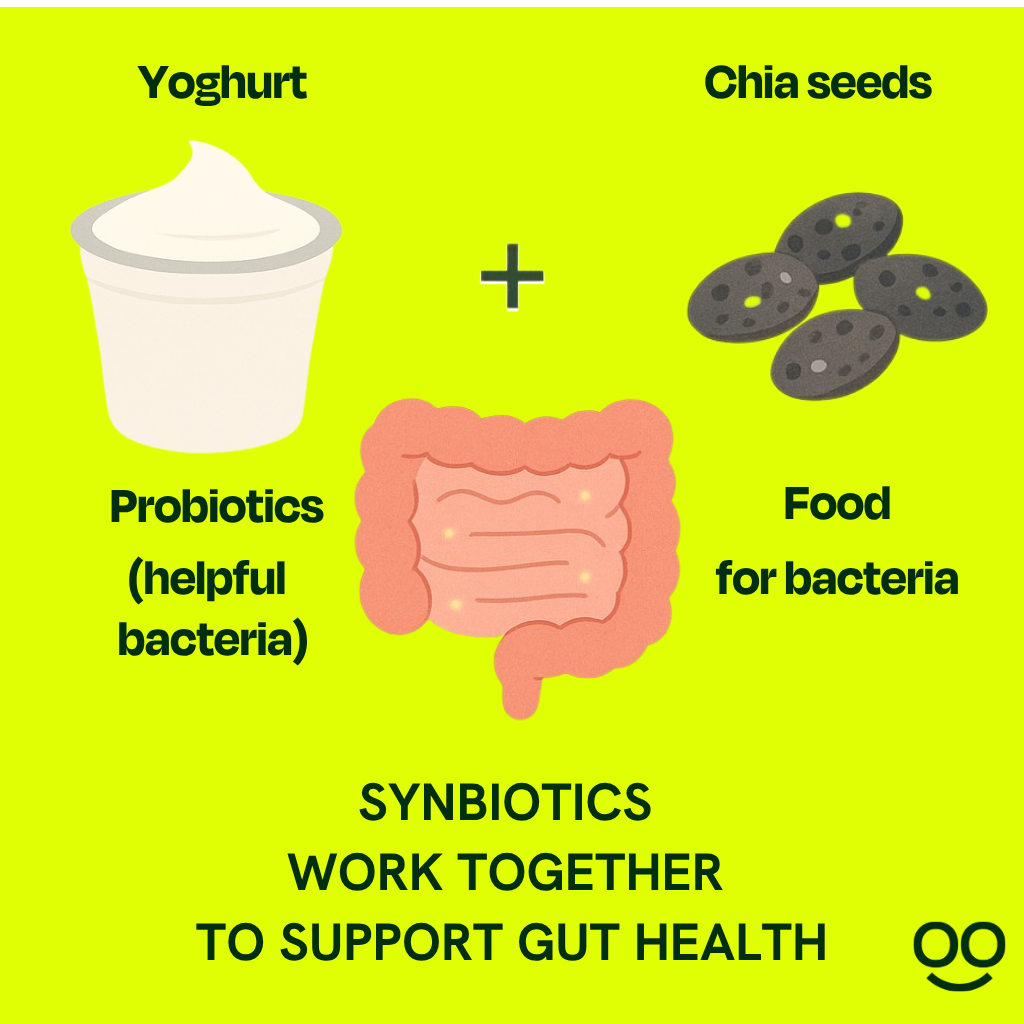

Fact-check: The implication of this post is that pairing fibre and dairy isn’t as supportive as people think it is.While it is true that there are ways to pack even more fibre to your breakfast, Greek yogurt and chia seeds each provide distinct nutritional benefits. More importantly, there is no evidence that pairing them is misguided. In fact, it might well be the opposite as they can work together as a synbiotic to support gut health. For a lot of people, adding fibre-rich foods like chia seeds to foods they already consume is a convenient way to increase their fibre intake.

What each food brings to the bowl

Yoghurt gives you quality protein, calcium, and live cultures that support a healthy gut. Calcium from dairy is well absorbed, usually in the 20 to 45 percent range depending on the product and context (source).

Chia seeds are tiny nutrition tanks. They are rich in soluble and insoluble fibre, plant omega-3 fat, and useful minerals. Reviews consistently report that chia seeds are very high in fibre and notably alpha-linolenic acid, the plant omega-3 that many of us under-consume (source).

Together, they can work as a synbiotic

A synbiotic is a combination of good bacteria and the food that helps them grow, working together to support your body’s health. In other words, yoghurt supplies helpful bacteria and chia’s soluble fibre forms a mild gel that microbes like to eat. Expert groups updated this definition in 2020 to make it clearer and more practical (source).

We also see a pattern in yoghurt research. Adding fermentable plant fibres, such as inulin, can help probiotic survival during storage and may improve texture. Chia’s mucilage is a fibre gel that behaves similarly in fermented dairy. Studies that added chia seeds or chia mucilage to yoghurt, including goat and cow milk versions, reported acceptable microbiology and good texture through chilled storage. That is the profile of a sensible functional add-in, not a harmful one (source).

“If you eat chia seeds with yoghurt rather than water, you get more benefits for your gut and microbiome. Yoghurt contains live bacterial cultures like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria. Chia's soluble fibre and mucilage act as prebiotics, thus feeding these bacteria. When eaten together, you get this natural symbiotic effect. Probiotics in the yoghurt have a ready source of fermentable carbohydrates, which can improve short-chain fatty acid production. That is 'the good stuff', which is 'gold dust’ for your health.

Furthermore, the calcium, vitamin D, and fat in the yoghurt enhance the absorption of fat-soluble compounds in the chia, namely ALA omega-3 fatty acids. One of the biggest benefits of eating more fibre is appetite regulation. When you combine fibre from the chia seeds and protein and fat from the yoghurt, you get even more satiety signals and even more stimulation of natural fullness hormones like GLP-1, cholecystokinin, PYY, etc.. This means you feel fuller for longer compared to chia water. When you combine dairy proteins and peptides from the yoghurt with fibre in the chia seeds, you get a slower, more consistent fermentation of those compounds in the colon. This leads to a wider range of short-chain fatty acids which are produced, such as butyrate and propionate.”

What about phytic acid?

Although Kara did not raise phytic acid in her post, we are including the following explanation to address a common question some readers have about chia seeds and mineral absorption.

Like many seeds, chia contains phytate, which can bind minerals in the gut. Typical levels in chia are about 1 to 1.2 grams per 100 grams of dry seed, and European safety reviewers have not flagged phytate in chia as a consumer risk at customary intakes.

Now zoom out to the real portion size. Most people use one to two tablespoons, not half a bag. Dairy calcium also remains reasonably bioavailable in mixed meals. So while phytate can nudge mineral absorption down in theory, there is no evidence that a normal sprinkle of chia “cancels” the calcium in yoghurt for healthy people. Soaking or hydrating chia before eating is sensible for texture and may modestly reduce phytate, though the effect varies by seed (source).

A simple way to do it well

Stir 1 to 2 tablespoons of chia into ¾ to 1 cup of plain yoghurt.

Let it sit for 10 to 15 minutes so the seeds hydrate and the gel forms.

Add fruit or spices for flavour. If you want sweetness, use whole fruit or a light drizzle of honey.

This gives you a protein-plus-fibre snack that tends to keep you full and steady. In product studies, adding chia or its mucilage improved yoghurt thickness and reduced whey separation, which many people enjoy. Honey, used sparingly, can also be compatible with probiotic survival, although health outcomes in healthy adults may not change (source).

Smart tweaks for extra benefit

• Choose your base. If you suffer from intolerances, allergies or if you are plant-based/vegan, use lactose-free yoghurt or a fortified plant yoghurt with live cultures. Aim for at least 120 mg calcium per 100 g on the label. Probiotic counts and calcium absorption vary by product, but both dairy and fortified non-dairy options can contribute meaningfully (source).

• Build a balanced bowl. Add berries, sliced kiwi, or grated apple for polyphenols and vitamin C. Sprinkle cinnamon or cocoa for flavour without much sugar. Keep portions comfortable for your gut.

For more practical information on how to gradually build up your fibre intake, check out our related guide and fact-check on fibremaxxing.

Final take away

For most people, the evidence doesn’t show that yoghurt harms the gut. In fact, and especially when pairing it with chia seeds, it’s quite the opposite. The pairing is nutritionally sound, common in research, and supports a diverse microbiome when part of a balanced diet.

Disclaimer: Kara Swanson didn't provide us with evidence to support her claims and asked us not to publish this fact-check, which she feels misrepresents her views. We have amended the article to ensure the claims made in the video were accurately portrayed. If provided with evidence, we will update the article.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources

- Swanson KS., et al. (2020). “ISAPP consensus statement on synbiotics.”

- Shkembi B., et al. (2021). “Calcium absorption varies by food matrix.”

- Fairweather-Tait SJ., et al. (1989). “Calcium absorption from milk.”

- Kruger MC., et al. (2023). “Range of calcium absorption from cow’s milk.”

- Kulczyński B., et al. (2019). “Chemical composition and nutritional value of chia.”

- Vera-Cespedes N., et al. (2023). “Physico-chemical and nutritional properties of chia.”

- Nakov G., et al. (2024). “Yoghurt enriched with chia seeds: quality over storage.”

- Hovjecki M., et al. (2024). “Chia mucilage improves goat milk yoghurt quality.”

- Rezaei R., et al. (2012). “Inulin improves probiotic survival in yoghurt.”

- Hussien H., et al. (2022). “Inulin enhances growth of yoghurt cultures.”

- EFSA Panel (2019). “Safety of chia seeds as a novel food.”

- American College of Gastroenterology, 2014. Chia seed choking case report and guidance.

- Gupta RK., et al. (2013). “Reducing phytic acid by soaking and cooking, overview across seeds.”

- Austria JA., et al. (2008). “Milling improves ALA availability from flaxseed, a relevant analogue.”

- Nieman D., et al. (2013). “Fatty acid bioavailability study of single oral doses of milled chia seed snack clusters or chia seed oil in healthy subjects.”

Moosavian S., et al. (2020). “Effects of dairy products consumption on inflammatory biomarkers among adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.” - Misselwitz B., et al. (2019). “Update on lactose malabsorption and intolerance: pathogenesis, diagnosis and clinical management.”

- Luyt, D., et al. (2014). “BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of cow's milk allergy.”

- Moosavian, SP. et al. (2020). “Effects of dairy products consumption on inflammatory biomarkers among adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.”

- Nieman, K. M., et al. (2021). “The Effects of Dairy Product and Dairy Protein Intake on Inflammation: A Systematic Review of the Literature.”

- Marco, ML. et al. (2016). “Health benefits of fermented foods: microbiota and beyond.”

- Leeuwendaal, NK. et al. (2022). “Fermented Foods, Health and the Gut Microbiome.”

- Misselwitz B., et al. (2019). “Update on lactose malabsorption and intolerance: pathogenesis, diagnosis and clinical management.”

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)