Fear or Facts? What Joe Wicks’ “KILLER” protein bar reveals about the real problem with ultra-processed food debates

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

The shock that stole the show

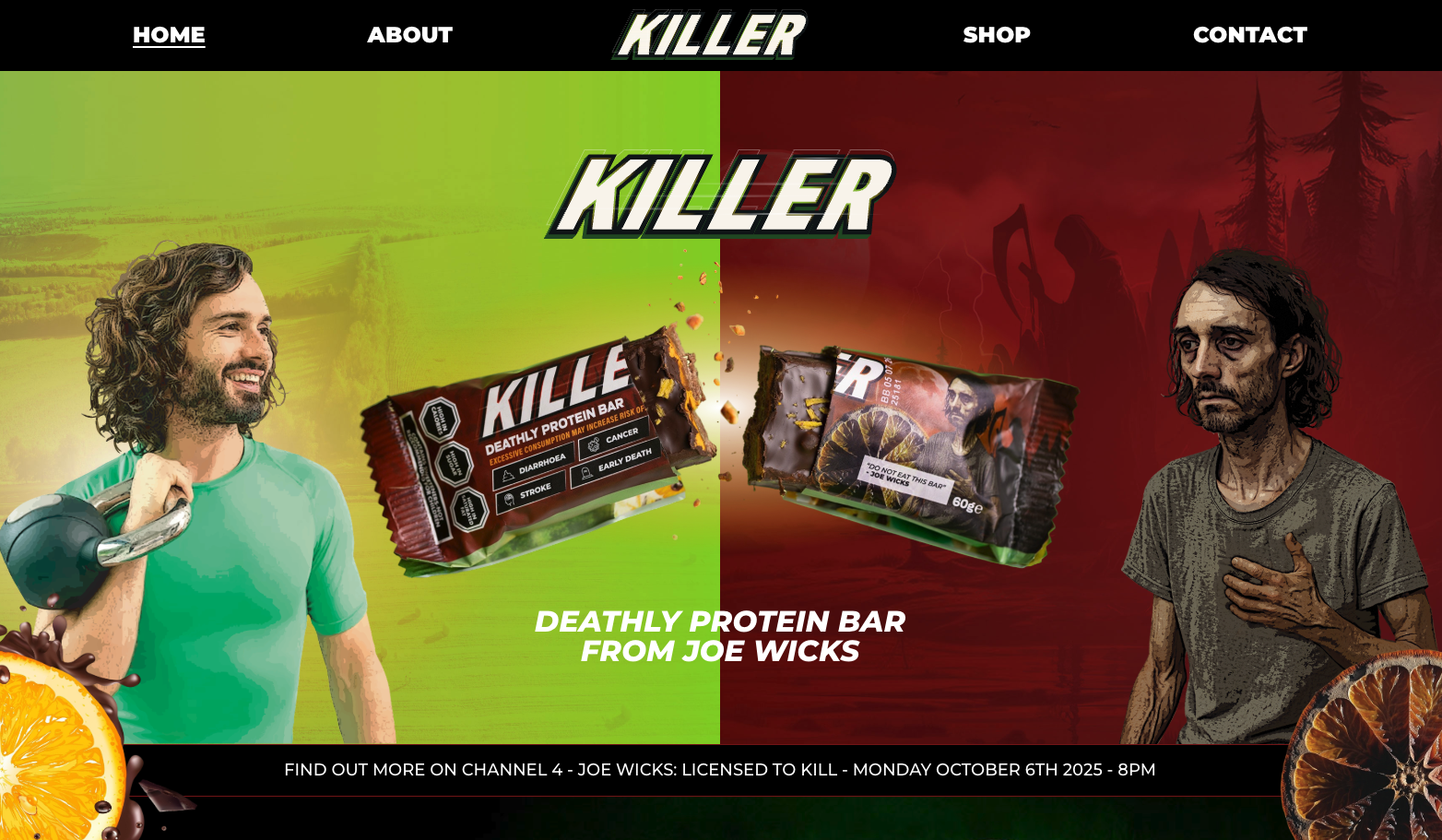

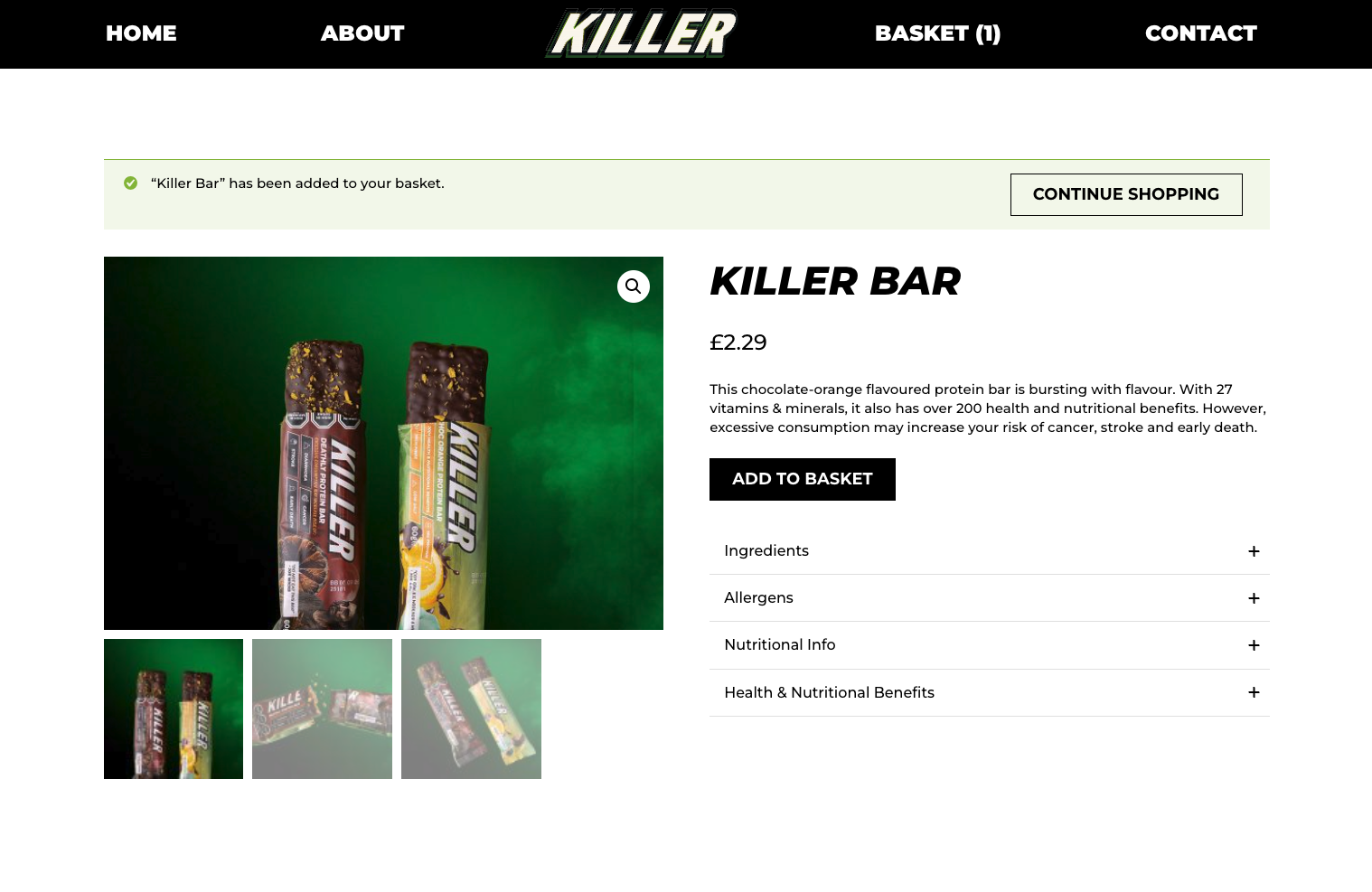

Joe Wicks’ latest project, an intentionally “unhealthy” protein bar named KILLER, was never meant to be launched quietly. It was engineered to provoke. With 96 ingredients, warnings about cancer and early death, and a documentary spotlight on the chaos of food marketing, the stunt achieved exactly what it set out to do: get Britain talking.

But amid the headlines and hashtags, one thing was missing, clarity. The Channel 4 documentary, co-created by Wicks and Professor Chris van Tulleken, aimed to expose loopholes in UK food regulations and the perils of ultra-processed foods (UPFs). Instead, it left viewers with fear and confusion, and health professionals with a heightened reaction and a flurry of unanswered questions.

And that’s where this conversation needs a reset.

The good intentions, and the missing science

Let’s start with some credit where it’s due. Joe Wicks has done extraordinary work getting families moving and thinking about nutrition. He clearly wants to make a difference. The intention behind the “KILLER” campaign, calling out misleading health claims and pushing for clearer food labelling, is commendable.

But intent isn’t enough when public trust and health literacy are on the line.

Perhaps it takes something shocking to cut through in today’s media landscape. But there’s a crucial difference between raising awareness and creating real change, and that gap matters. This campaign, likely advised by a production company, prioritised impact over nuance.

The issue here is that the message lacked the scientific depth and expert collaboration needed to make it constructive, with minimal regard for the emotional impact on viewers.

Health communication is impactful when influencers and experts work together. When they don’t, public health messaging risks veering into confusion, not clarity.

Why we need influencers, but with guardrails

It’s no secret that balanced, nuanced nutrition advice rarely trends. Fear, outrage, and “shocking truths” drive engagement far faster than measured science. That’s why influencers matter: they have the reach that scientists and policymakers don’t.

Campaigns like Marcus Rashford’s push for free school meals or Jamie Oliver’s school food reforms worked because they paired influence with expertise.

Wicks and van Tulleken’s documentary, on the other hand, shows what happens when a well-intentioned message is stripped of context, especially when context is what people need most.

Where “KILLER” missed the mark

1. Fear Over Facts

The dark lab scenes, the ominous warnings, the “KILLER” label, it’s theatre, not science. While it makes for gripping television, it also fuels anxiety. Without clarity on which ingredients are harmful, in what amounts, or why, the message becomes distorted.

The phrase “dose makes the poison” may sound tedious, but it’s scientifically accurate. Context matters. Even water can be harmful in excess. A protein bar occasionally won’t harm you, but the campaign implied otherwise.

2. Oversimplifying the “UPF Problem”

The term ultra-processed is a messy one. It lumps together everything from energy drinks to baby formula, fortified cereals, and plant-based milk. Are they nutritionally equivalent? Of course not.

UPFs are a diverse group, and the current system of classification doesn’t account for nutrient content or real-world use. Many people depend on UPFs, because of medical conditions, sensory sensitivities, time, or cost. Demonising an entire category of foods risks alienating those who don’t have the privilege of choice.

That doesn’t mean our current food environment is one we should just accept though. We do have to have tough conversations, but ultimately processing level does not equal healthfulness.

The question shouldn’t be “is it processed?” but rather “what’s actually in it?” and “what else is in my diet?”

3. Ignoring the systemic barriers

For millions, the challenge isn’t confusion about ingredients, it’s access. One in five people in the UK lives in poverty. When nutritious food is unaffordable or unavailable, no amount of labelling can fix the problem.

The core issues driving poor nutrition are structural: wealth inequality, food pricing, and time poverty. Fear-based campaigns rarely acknowledge that.

4. No clear endgame

What’s the solution here? Stricter labelling? Ingredient bans? A campaign for government reform? The documentary didn’t say what the next steps are, but one can hope that there is indeed a plan.

Awareness without direction can lead to cynicism, and public health can’t afford that.

What consumers actually need

Instead of fear, people need clarity, reassurance, and tools they can use in real life:

- Focus on dietary patterns, not single foods. What you eat most of the time matters more than one meal or snack.

- Read labels for salt, sugar, saturated fat, and fibre - not just ingredient list length or processing methods

- Make swaps that suit your life, your budget, and your time. Reduce where it makes sense for you and your family.

- Let go of guilt. Balance matters more than perfection. Nutrition is personalised.

A protein bar, even one with 96 ingredients, won’t make or break your health. What matters is what you eat most of the time.

The Bigger Picture: Policy, Not Panic

If we’re serious about change, the solutions are systemic, not sensational:

- Subsidise nutritious foods so they’re affordable.

- Support reformulation to improve the quality of convenience foods.

- Implement labelling clarity and tighten the rules on misleading nutrition and health claims.

- Link nutrition policy with environmental and affordability goals.

Warning labels alone won’t transform public health, but a coordinated food systems strategy might.

The Evidence We Actually Have

The science on UPFs is still evolving. Most studies are observational, meaning they can show correlations but not cause-and-effect. What we do know, from decades of research, is this: diets rich in minimally processed, plant-forward foods support health and longevity.

That doesn’t mean cutting out convenience, it means making it work for you. Combining home-cooked meals with ready-made options can still be part of a healthy lifestyle. Perfection isn’t the goal; sustainability is.

A Missed Opportunity, But a Valuable Conversation

The “KILLER” bar may not have delivered the science it promised, but it did succeed in one important way: it got people talking. And now, the conversation needs to move beyond outrage and into action.

If influencers used their platforms to push for equitable food access, cooking education in schools, or stronger regulation on health claims - alongside nutrition experts and policymakers - that would have a transformative impact. The reach is there. The expertise exists. What’s missing is the collaboration.

Public health needs passion, but it also needs precision. Campaigns built on fear fade fast. Campaigns built on collaboration, science, and empathy endure.

Final Insight:

Food reform doesn’t start in a TV lab, it starts in our communities, our policies, and our shared commitment to understanding, not fearing, what’s on our plates.

The conversation happening right now matters - but it needs nuance, compassion, and science at the centre.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)