Aeronutrients: Why that breath of fresh air might be nourishing your body

You know that feeling you get when you take a breath of fresh air in nature? There may be more to it than a simple lack of pollution.

When we think of nutrients, we think of things we obtain from our diet. But a careful look at the scientific literature shows there is strong evidence humans can also absorb some nutrients from the air.

In a new perspective article published in Advances in Nutrition, we call these inhaled nutrients "aeronutrients" – to differentiate them from the "gastronutrients" that are absorbed by the gut.

We propose that breathing supplements our diet with essential nutrients such as iodine, zinc, manganese and some vitamins. This idea is strongly supported by published data. So, why haven't you heard about this until now?

Breathing is constant

We breathe in about 9,000 litres of air a day and 438 million litres in a lifetime. Unlike eating, breathing never stops. Our exposure to the components of air, even in very small concentrations, adds up over time.

To date, much of the research around the health effects of air has been centred on pollution. The focus is on filtering out what's bad, rather than what could be beneficial. Also, because a single breath contains minuscule quantities of nutrients, it hasn't seemed meaningful.

For millennia, different cultures have valued nature and fresh air as healthful. Our concept of aeronutrients shows these views are underpinned by science. Oxygen, for example, is technically a nutrient – a chemical substance "required by the body to sustain basic functions".

We just don't tend to refer to it that way because we breathe it, rather than eat it.

How do aeronutrients work, then?

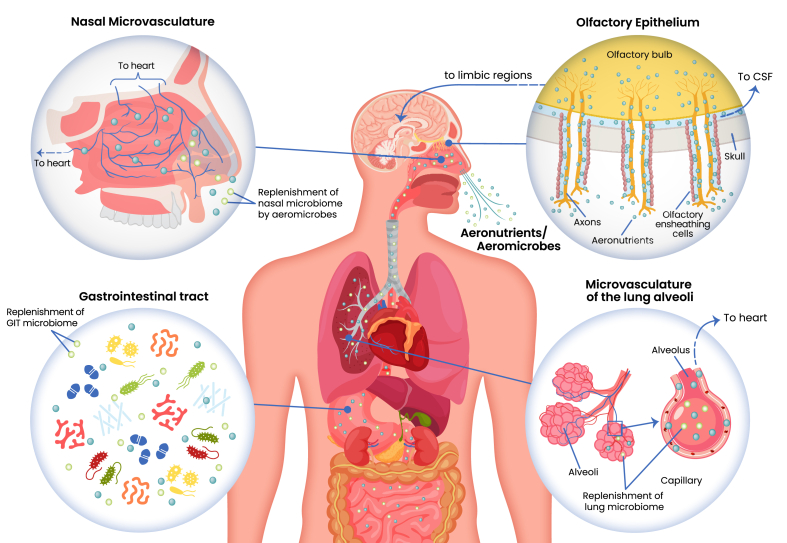

Aeronutrients enter our body by being absorbed through networks of tiny blood vessels in the nose, lungs, olfactory epithelium (the area where smell is detected) and the oropharynx (the back of the throat).

The lungs can absorb far larger molecules than the gut – 260 times larger, to be exact. These molecules are absorbed intact into the bloodstream and brain.

Drugs that can be inhaled (such as cocaine, nicotine and anaesthetics, to name a few) will enter the body within seconds. They are effective at far lower concentrations than would be needed if they were being consumed by mouth.

In comparison, the gut breaks substances down into their smallest parts with enzymes and acids. Once these enter the bloodstream, they are metabolised and detoxified by the liver.

The gut is great at taking up starches, sugars and amino acids, but it's not so great at taking up certain classes of drugs. In fact, scientists are continuously working to improve medicines so we can effectively take them by mouth.

The evidence has been around for decades

Many of the scientific ideas that are obvious in retrospect have been beneath our noses all along. Research from the 1960s found that laundry workers exposed to iodine in the air had higher iodine levels in their blood and urine.

More recently, researchers in Ireland studied schoolchildren living near seaweed-rich coastal areas, where atmospheric iodine gas levels were much higher. These children had significantly more iodine in their urine and were less likely to be iodine-deficient than those living in lower-seaweed coastal areas or rural areas. There were no differences in iodine in their diet.

This suggests that airborne iodine – especially in places with lots of seaweed – could help supplement dietary iodine. That makes it an aeronutrient our bodies might absorb through breathing.

Manganese and zinc can enter the brain through the neurons that sense smell in the nose. Manganese is an essential nutrient, but too much of it can harm the brain. This is seen in welders, who are exposed to high levels from air and have harmful levels of manganese buildup.

The cilia (hair-like structures) in the olfactory and respiratory system have special receptors that can bind to a range of other potential aeronutrients. These include nutrients like choline, vitamin C, calcium, manganese, magnesium, iron and even amino acids.

Research published over 70 years ago has shown that aerosolised vitamin B12 can treat vitamin B12 deficiency. This is super important for people who have high B12 deficiency rates, such as vegans, older people, those with diabetes and those with excessive alcohol intake.

If we accept aeronutrients, what next?

There are still a lot of unknowns. First, we need to find out what components of air are beneficial for health in natural settings like green spaces, forests, the ocean and the mountains. To date, research has predominantly focused on toxins, particulate matter and allergens like pollen.

Next, we would need to determine which of these components can be classified as aeronutrients.

Given that vitamin B12 in aerosol form is already shown to be safe and effective, further research could explore whether turning other micronutrients, like vitamin D, into aerosols could help combat widespread nutrient deficiencies.

We need to study these potential aeronutrients in controlled experiments to determine dose, safety and contribution to the diet. This is particularly relevant in places where air is highly filtered, like airplanes, hospitals, submarines and even space stations.

Perhaps we will discover that aeronutrients help prevent some of the modern diseases of urbanisation. One day, nutrition guidelines may recommend inhaling nutrients. Or that we spend enough time breathing in nature to obtain aeronutrients in addition to eating a healthy, balanced diet.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘Game changer’ or gimmick: a deep dive into alkaline and low PRAL diets

Claim 4: “Eating acidic foods triggers the release of stress hormone cortisol, which is needed to process and digest the meal, and the body has to work harder to regulate it causing cortisol to spike even further. High levels of cortisol have been shown to disrupt metabolism, increase appetite and promote fat storage, particularly in the stomach.”

Fact-check: Here again it is the wording that makes this claim slightly misleading; suggesting that this is established evidence while not making clear that more research is needed to confirm associations.

We know that consistently high PRAL diets can cause low grade metabolic acidosis. One of the body’s responses to this is release of the hormone cortisol. Cortisol has a number of functions but in this case it breaks down muscle proteins into amino acids (the building blocks of proteins) that the body can convert to bicarbonate (a base) which neutralises excess acid. Cortisol also increases the removal of acid by the kidneys. However it is important to note that this cortisol release is a response to maintain acid-base balance, not specifically to process or digest the meal.

There is less evidence to support ‘acidic foods’ ‘disrupt(ing) metabolism’. As most studies are observational, it comes back to correlation vs causation. We do not yet have concrete evidence to support direct causation. Similarly to the previous claim, is it that acidic foods directly increase cortisol that impacts metabolism? Or are there other factors at play such as overall diet or calorie intake? More research is needed to know for sure.

Overall, this claim is partly supported but lacking in nuance and evidence. Melanie Betz emphasises that balance is key:

PRAL isn't about individual “acidic foods” - it is about the overall BALANCE of your diet. Eating high PRAL steak is probably FINE if you aren't eating a giant portion and balance it with more alkaline producing foods like a potato and asparagus. Like so many fad diets, this scientific truth ("certain foods produce acid/aklai") is taken too far and used to inappropriately demonize foods. Like SO many things in nutrition, it is crucial to look at entire dietary PATTERNS and not individual "good" or "bad" foods.

Is this diet really a game changer? … Probably not in the ways the article suggests.

The Daily Mail’s claims promise quick fixes: “better than weight loss jabs”, “burn fat fast”, “slash your health risks”and “no side effects”. These are based largely on a single study with little explanation of the mechanisms or limitations behind the findings. As is often the case, the reality is far more nuanced.

The statements in the article aren’t entirely false, but the implication that the long-debunked alkaline diet is now supported by science is misleading. Low-PRAL diets are not a new or updated version of the alkaline diet. Rather, potential renal acid load (PRAL) is a well-established concept in physiology that reflects how the kidneys maintain acid–base balance. While there are overlaps in the types of foods encouraged (fruits, vegetables, legumes) and the involvement of pH, equating the two oversimplifies and confuses the science.

Do we need to worry about PRAL?

There indeed may be benefits to a low-PRAL diet, particularly, for those with Chronic Kidney Disease and those prone to oxalate or uric acid kidney stones with certain urine risk factors. However, for healthy individuals, pursuit of an overly restrictive ‘low-PRAL’ or ‘alkaline’ diet may lead to unnecessary food rules, potential nutrient deficiencies, and in worst cases, disordered eating patterns. As always, any dietary changes should always be guided and overseen by a dietitian to ensure they are carried out properly and safely.

Processes in the body are complex and nutrition science rarely offers black-and-white answers. This emerging research is interesting, but what it really points to is the need for more research. High-quality, long-term studies are needed to confirm these associations and clarify underlying mechanisms.

The bottom line:

What we do know with confidence is that diets rich in fruits, vegetables, and legumes - all naturally lower in PRAL - are associated with better overall health outcomes. Whether those benefits stem from a reduced acid load, higher nutrient density, or increased fibre and phytochemicals (or all of the above) remains to be seen.

In the meantime, this line of research doesn’t really change the fundamentals of healthy eating. The most evidence-backed advice remains the same: Eat a balanced diet based on mostly whole foods, with plenty of fruits, vegetables, and plant-based proteins, while limiting processed foods, added sugars, and excessive meat intake.

Alkaline or not, the key to good nutrition, as the article concedes, is balance.

We have contacted the Daily Mail and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Claim 3: ‘‘The more alkaline (negative-PRAL) foods you eat, the easier it is for the body to lose weight,… Low-fat, vegan foods can help reduce the risk of diabetes, lower stress levels and help shed excess fat, without muscle-loss.”

Fact-check: This claim is based on one single study with clear confounding variables. Before giving dietary advice for the general population, it is important to have consistent evidence from multiple large scale, long-term studies.

The claims made are based on a recent study that compared a low-fat vegan diet with a Mediterranean Diet. The study found that a low-fat vegan diet had lower PRAL, and there was an association between this lower PRAL and increased weight loss.

However there are a couple of important aspects of the study to consider:

A low-fat vegan diet and Mediterranean Diet are both considered lower in PRAL than a standard Western diet. Therefore comparing them may not be the best way to measure the effect of low-PRAL diets.

Additionally, as fats have a higher calorie density, it is likely that the low-fat vegan diet was lower in calories than a Mediterranean Diet which has a high focus on nuts, seeds, olive oil and oily fish - foods that are higher in healthy fats and thus higher in calories.

Here we must remember the difference between correlation and causation. Just because there was a correlation between the lower PRAL, low-fat vegan diet and weight loss, does not mean that it was low PRAL that caused the weight loss. In this case there is a clear confounding variable: the difference in calories.

In other studies, Mediterranean Diets have also been shown to be beneficial, particularly for sustainable weight loss (source), so there is clearly more at play here.

Did participants lose weight because the foods were low in PRAL, or because low-PRAL foods mainly consist of fruits, vegetables, and legumes? These foods are already known to be low in calories, high in water and fibre, rich in beneficial nutrients and phytochemicals, and overall linked to better health outcomes and weight loss.

When thinking of general nutrition advice, the key is that it should be applicable to everyone and backed by concrete research. There are many aspects to consider when creating public health and dietary guidelines. In this case larger, long-term studies, with more direct measurements of PRAL and energy intake are needed to confirm if these weight loss claims are really due to lower PRAL or not. While one study alone may provide helpful information and inspire future research, it is not enough evidence to give advice to the general population. Melanie Betz questions whether this new way of categorising foods as either 'good' or 'bad' depending on their PRAL value is helpful for consumers, or whether it might do more harm than good:

A note on pH

What is pH?

Before analysing the article’s claims further, it is important to understand some of the key terms used throughout the article, and put them into context.

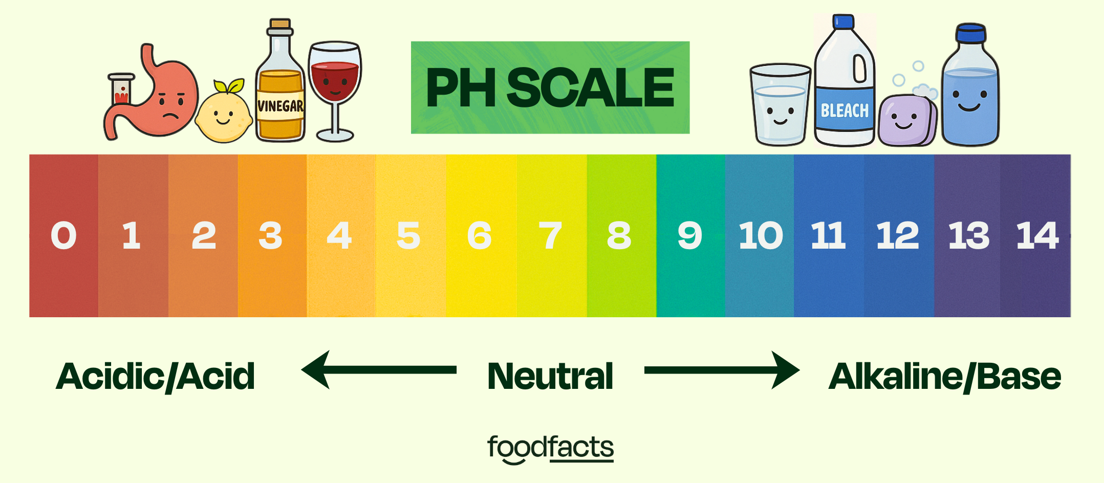

pH: In scientific terms pH is a measure of hydrogen ions in a solution. In layman’s terms it is a way of measuring how acidic or alkaline a liquid is.

pH is measured on a scale that runs from 0-14.

Acidic/Acid: This refers to a substance with a pH below 7. For example, stomach acid, lemon juice and vinegar are all acidic.

Alkaline/Base: This refers to a substance with a pH above 7. For example, baking soda, soap and bleach are all alkaline.

Neutral: This refers to a substance with a pH of 7. It is neither acidic or alkaline. For example, pure water.

Why does pH matter in the body?

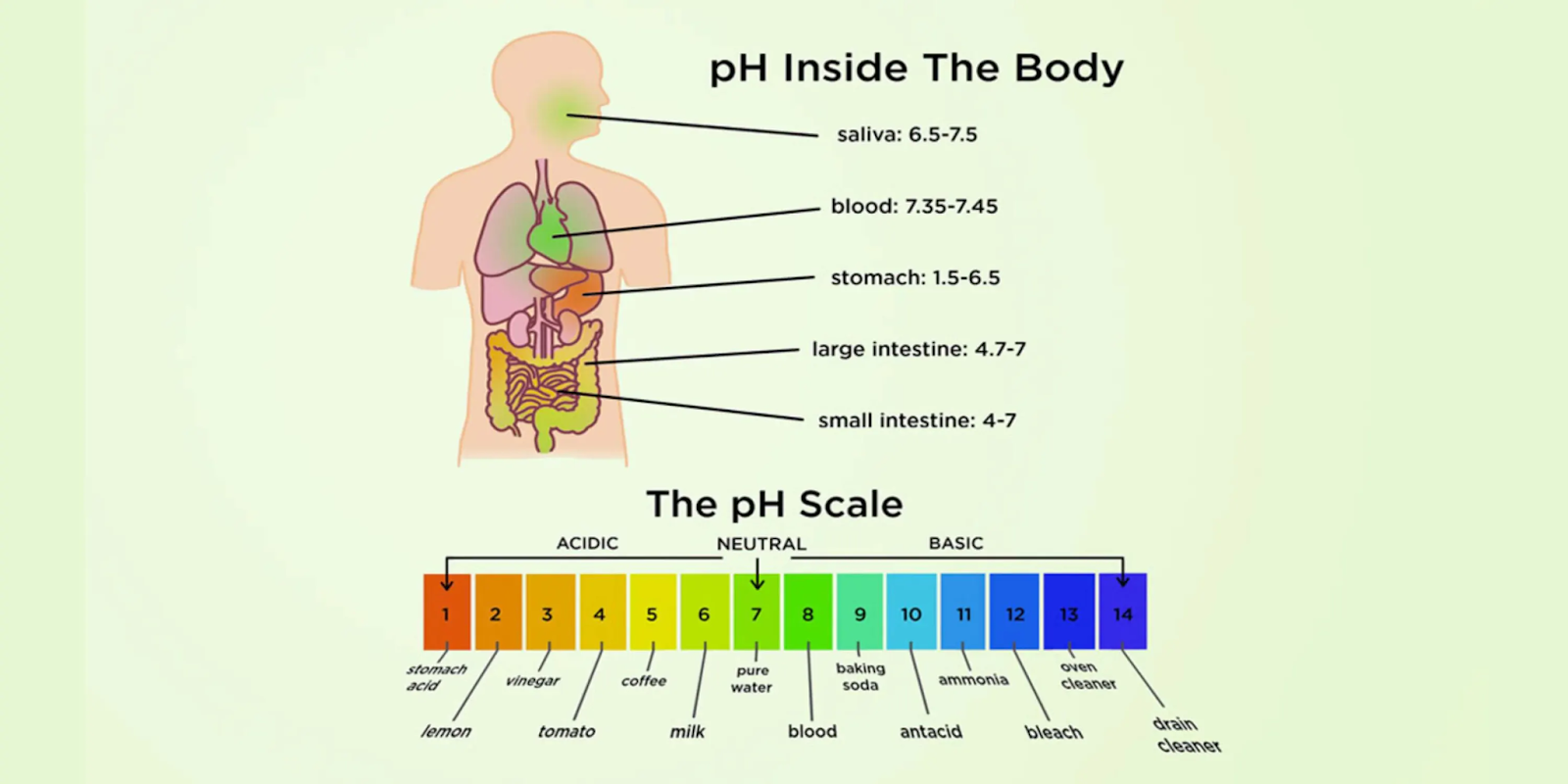

The body has tight mechanisms in place to maintain pH homeostasis (or pH balance). Certain areas in the body depend on having the correct pH. For example, blood pH must be maintained in a very narrow range of 7.35-7.45. If blood pH moves too far out of this range, it can cause acidosis (too acidic) or alkalosis (too alkaline). Both of these can be dangerous, and in extreme changes of pH even cause death, due to the effect on certain proteins and enzymes needed for vital bodily functions.

The alkaline diet: a quick history

Originally, the alkaline diet claimed to alter the body’s pH depending on the food that you ate. It emphasised so-called ‘alkaline foods’ such as fresh fruits and vegetables, nuts, seeds and plant proteins while limiting so-called ‘acidic foods’ such as meat, dairy, processed cereals, and refined sugars. This change in body pH was claimed to improve overall health and prevent a number of diseases.

However, this classification of ‘acidic’ and ‘alkaline’ foods was inconsistent and largely inaccurate. For example some processed foods, such as canned or frozen vegetables and beans are not necessarily acidic, even though the diet categorised them as such.

Due to these inconsistencies, and the fact that the body’s pH is tightly regulated, the initial proposition of an alkaline diet was quickly dismissed by scientists and healthcare professionals alike. The idea of altering the body’s pH was simply impossible and it was assumed that any potential benefits were due to the removal of ultra-processed foods, sugar or caffeine and an increase in fruits and vegetables.

But does this new research pose a different story or has this fad just had a rebrand?

Claim 1: “The modern approach is based on a measurable concept, called potential renal acid load, or PRAL…. This estimates the amount of acid the kidneys must excrete after food…”

Fact-check: The information provided on PRAL is mostly accurate, however the article implies low PRAL diets are a new science-backed version of the alkaline diet. This is misleading, as the two are actually distinctly different concepts.

So what is PRAL?

As discussed above, the body has tight mechanisms in place to control blood pH and ensure correct bodily functions. One of these mechanisms is via the kidneys (the other main mechanism is via the lungs).

The kidneys help regulate blood pH by filtering out excess acids or bases through the urine. They do this by reabsorbing bicarbonate (a base) and excreting hydrogen ions (an acid), helping to keep the blood’s pH tightly regulated.

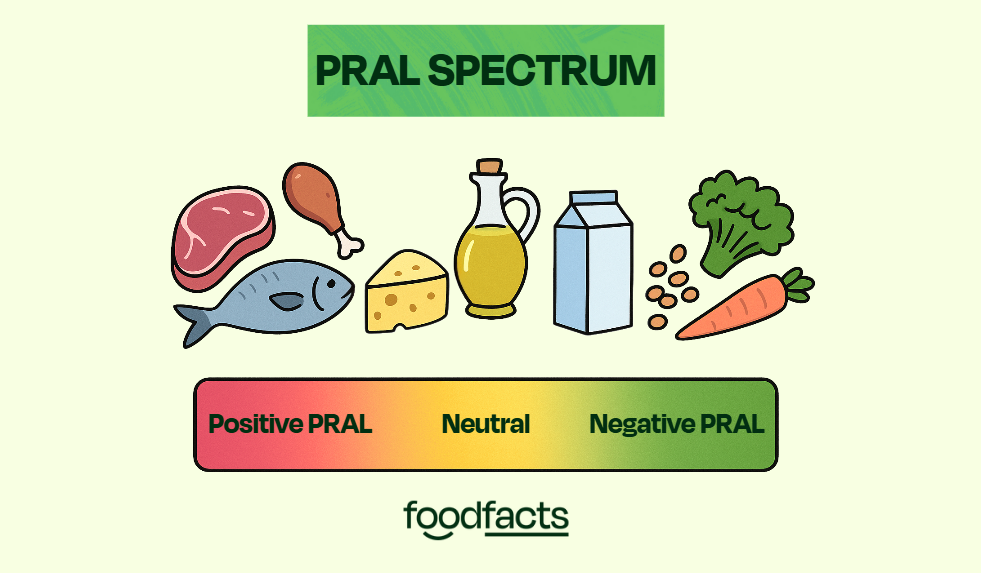

Potential renal acid load (PRAL) refers to this process and how much acid is excreted by the kidneys after breaking down food.

-Positive PRAL foods contain more acid-producing nutrients such as protein and phosphorus and therefore increase net acid excretion. Examples include meat, poultry, fish, seafood and cheese.

-Negative PRAL foods contain base-producing nutrients such as potassium, magnesium, and calcium. Examples include fruits, vegetables and some beans, nuts and legumes.

It is important to note that unlike the alkaline diet, PRAL does not reflect blood pH, which in healthy individuals always remains in that 7.35-7.45pH range. It instead is an indication of how hard the kidneys are working to maintain blood pH (source).

While the explanation of PRAL in the article is largely correct, describing this as a ‘modern approach’ to the alkaline diet may unintentionally imply that high- and low-PRAL diets alter blood pH which, as previously discussed, is not the case in healthy individuals.

Claim 2: “It’s the long-term build-up of these by-products (sulphuric/phosphoric acid), researchers believe, that may contribute to chronic disease…’

Fact-check: There are some studies that show links between high-PRAL diets and certain chronic diseases. This is an interesting topic to watch, but for now, more research is needed to confirm these associations and understand the mechanisms behind them.

The wording here is slightly misleading as the acid by-products do not necessarily ‘build up’ in the body. As previously established the pH levels in the body are tightly regulated by the kidneys and lungs on a minute-to-minute and daily basis.

However there is research to suggest that continually high-PRAL diets may cause low grade metabolic acidosis. This is when the body’s pH shifts slightly towards acidic (aka closer to a pH of 7.35) and it has been linked to some chronic diseases, such as osteoporosis, type 2 diabetes, kidney stones and chronic kidney disease (source).

Is there evidence that positive/high-PRAL diets cause chronic disease?

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a condition that causes weakening of bones, leading to increased risk of fractures and breaks.

There is evidence that a high- PRAL diet may contribute to osteoporosis. For example, a systematic review and meta analysis found that higher dietary acid load is significantly associated with increased fracture risk. In higher quality studies specifically, there was a 12% higher risk of fractures.

This is likely due to low grade metabolic acidosis caused by high-PRAL diets. In order to neutralise the acid, bones will release calcium and other minerals which over time, weakens them, making them more prone to fractures.

Type 2 Diabetes

Type 2 Diabetes occurs when the body cannot use insulin correctly. Insulin is a hormone that helps cells take up glucose to use for energy, so this condition results in high blood sugar levels.

Another systematic review and dose-response meta analysis looked at 7 long-term studies. For every 5-point increase in PRAL there was a 4% higher risk of type 2 diabetes. Interestingly, this risk followed a U-shape, suggesting that both very low and very high PRAL diets may carry risk.

The authors speculated that this may occur because the body has shifted slightly to a more acidic state (low-grade metabolic acidosis). As a result less insulin is released by the pancreas and the insulin that is released works less effectively (also known as insulin resistance), and blood pressure also increases. Sugar therefore stays in the blood and blood sugar levels remain elevated.

Kidney Stones

Kidney Stones form in the kidneys when substances such as calcium, oxalate, or uric acid become too saturated in the urine and they form a stone. More acidic urine makes it easier for uric acid and calcium oxalate kidney stones to form. The higher PRAL diet you eat, the more acid your kidneys have to get rid of, making your urine more acidic. For this reason, eating a more alkaline producing diet is often a strategy to prevent kidney stones for people with high urine levels of acid or calcium, as well as low citrate. Citrate is an alkaline molecule that makes it harder for calcium kidney stones to form. A lower PRAL diet will promote the excretion of citrate in urine.

One study found associations between high-PRAL diets and the formation of calcium oxalate kidney stones.

Here we get a glimpse of how nuanced and interconnected the systems of the body really are, as it is the release of calcium from bones (as mentioned above in regards to osteoporosis) which leads to increased calcium in urine that could be one of the mechanisms behind this association.

Chronic kidney disease

Chronic kidney disease is a condition where the kidneys are less able to filter waste and excess fluid from the blood. A meta analysis of 23 studies examined the association between high-PRAL diets and chronic kidney disease. They found that people with a higher dietary acid load had a 31% increased risk of developing chronic kidney disease.

Mechanisms again are related to the low grade metabolic acidosis caused by high-PRAL diets. This shift towards a more acidic state can cause release of endothelin, a substance that in normal levels helps regulate circulation but in high levels can damage the kidneys over time. There can also be increases in the hormone aldosterone which can raise blood pressure, further contributing to kidney disease.

Often low-PRAL diets are recommended by healthcare professionals as a way to prevent and treat acidosis in those with chronic kidney disease.

Low-PRAL diets also help to control blood glucose and blood pressure, the leading causes of chronic kidney disease. So controlling these factors will in turn help to protect the kidneys. Again we see here how all these mechanisms can overlap and work alongside each other to contribute to overall health.

Bottom line

While the essence of this claim is accurate, emphasis on the word ‘may’ is needed.

The processes described above are complex. This research is promising, but while it can give us some useful insight, further studies are needed to confirm these findings and to give us a clearer picture of the processes taking place behind these observations. Melanie Betz is a Registered Dietitian specialising in kidney stones and Chronic Kidney Disease. She highlights the importance of small changes over an all-or-nothing mindset, a common pitfall when complex research is taken out of context:

“It is important to think about this on a spectrum - VERY high PRAL is likely not good - but just lowering it (not necessarily to a NEGATIVE number) is likely going to be beneficial for health.

To truly have a negative PRAL diet - you'd likely need to be nearly 100% vegetarian/vegan.“

"A lower PRAL diet will include more foods that we know are good for you like fruits, veggies and plant proteins. It is no secret that this is good for chronic disease prevention and overall health. However, I don't think that adding yet an EXTRA thing for people to be concerned about is going to help when making food choices.

From a scientific perspective, it is certainly an interesting line of study. But from a public health standpoint, do we really need another way to categorise foods as "good" or "bad"? It is also important to note that some very healthful foods do have a positive PRAL value (like whole grains), so I fear this categorisation would demonise them. Likewise, fats are always neutral, so by focusing on ALL "negative" PRAL foods, we would end up cutting out healthy fats like olive oil."

Be cautious of sweeping statements online. This article uses serious sounding medical terms without clearly explaining what they mean or how strong the evidence is. This lack of context can be misleading and often exaggerate the real risk.

A recent article by Meike Leonard of the Daily Mail claimed there may be more to the alkaline diet than we first thought. The article highlights a new study and goes on to suggest that alkaline foods could ‘slash health risks’ such as osteoporosis, type 2 diabetes and kidney disease as well as ‘lower stress levels and help shed excess fat’. But is this new evidence really a ‘game changer’? Let’s take a further look at what the science has to say.

Low-PRAL diets can indeed be a useful intervention, especially for those with chronic kidney disease and kidney stones, and some studies suggest they may be beneficial for other chronic diseases as well. However, for the general healthy population, the research is still limited and more evidence is needed to truly understand the science.

For now, the fundamentals of a healthy diet remain the same, with a key focus always being on whole foods, lots of fruits and vegetables and of course balance.

Framing low-PRAL diets as a “modern version” of the alkaline diet risks spreading confusion and encouraging unnecessary food restrictions. Bold, sweeping statements online can sound appealing, but in reality there is no silver bullet for health and nutrition.

Following overly restrictive diets that are not properly backed by research, or guided by the help of a healthcare professional, could do more harm than good and make healthy eating unnecessarily confusing and difficult.

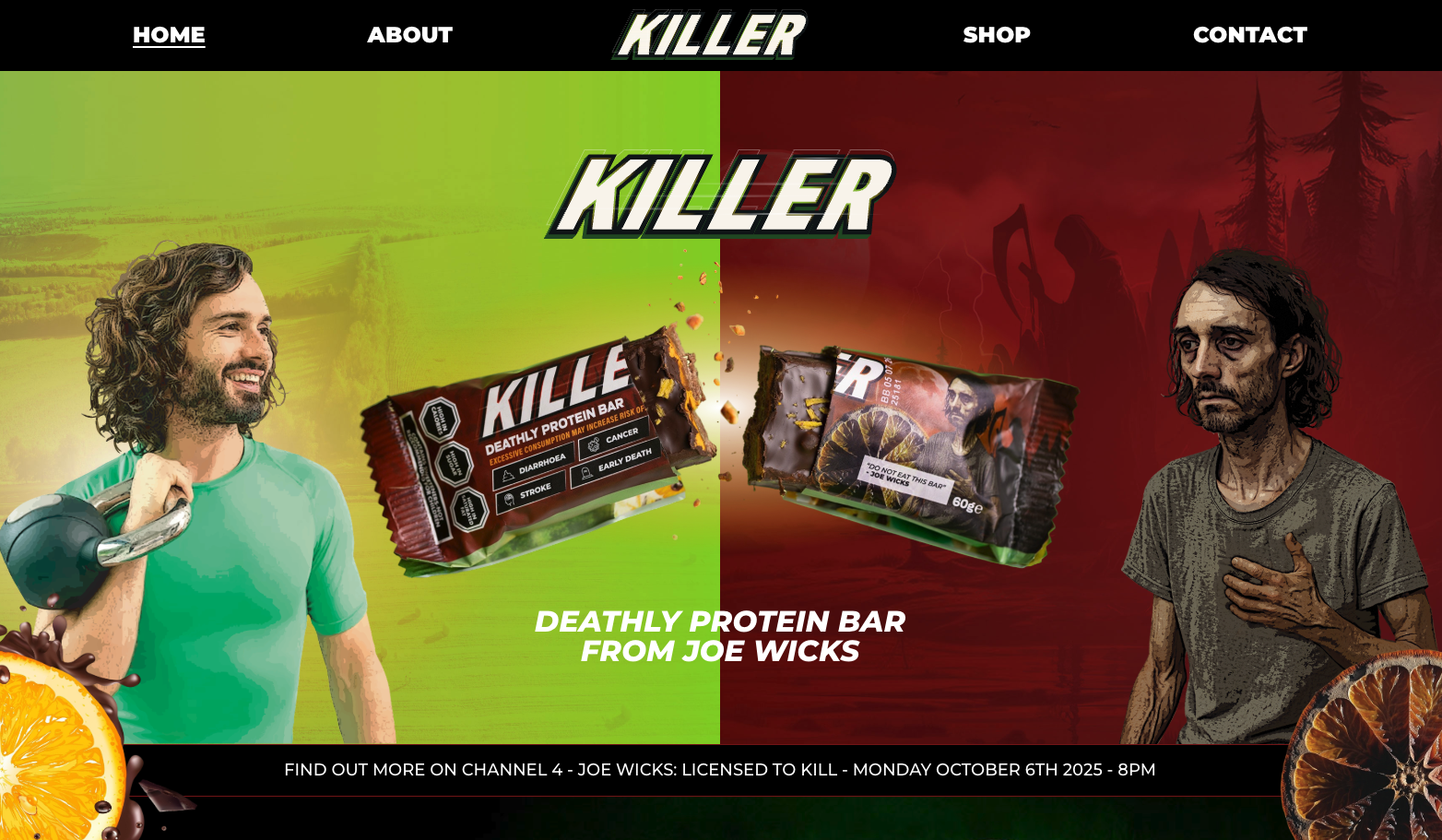

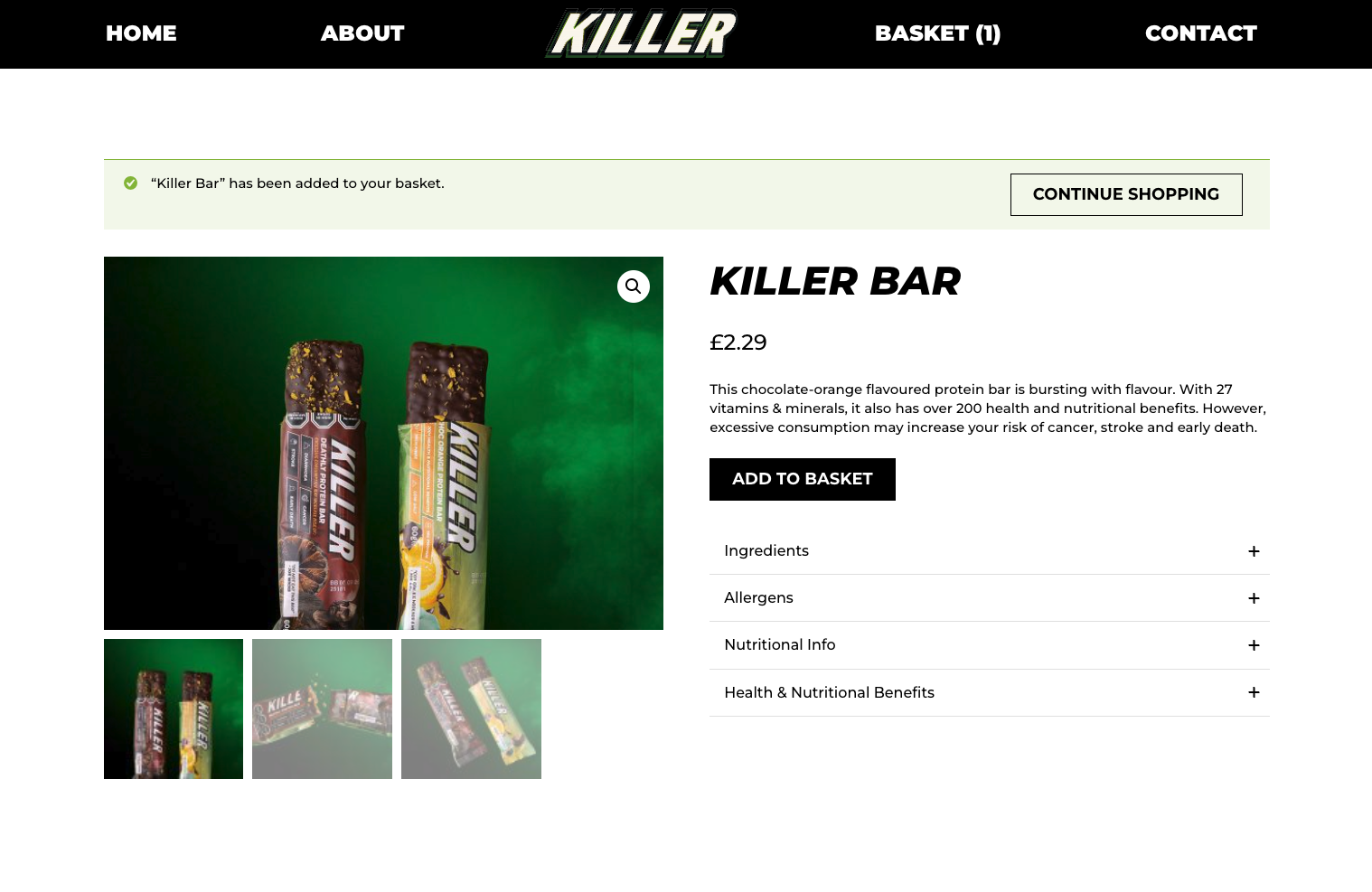

Fear or Facts? What Joe Wicks’ “KILLER” protein bar reveals about the real problem with ultra-processed food debates

The shock that stole the show

Joe Wicks’ latest project, an intentionally “unhealthy” protein bar named KILLER, was never meant to be launched quietly. It was engineered to provoke. With 96 ingredients, warnings about cancer and early death, and a documentary spotlight on the chaos of food marketing, the stunt achieved exactly what it set out to do: get Britain talking.

But amid the headlines and hashtags, one thing was missing, clarity. The Channel 4 documentary, co-created by Wicks and Professor Chris van Tulleken, aimed to expose loopholes in UK food regulations and the perils of ultra-processed foods (UPFs). Instead, it left viewers with fear and confusion, and health professionals with a heightened reaction and a flurry of unanswered questions.

And that’s where this conversation needs a reset.

The good intentions, and the missing science

Let’s start with some credit where it’s due. Joe Wicks has done extraordinary work getting families moving and thinking about nutrition. He clearly wants to make a difference. The intention behind the “KILLER” campaign, calling out misleading health claims and pushing for clearer food labelling, is commendable.

But intent isn’t enough when public trust and health literacy are on the line.

Perhaps it takes something shocking to cut through in today’s media landscape. But there’s a crucial difference between raising awareness and creating real change, and that gap matters. This campaign, likely advised by a production company, prioritised impact over nuance.

The issue here is that the message lacked the scientific depth and expert collaboration needed to make it constructive, with minimal regard for the emotional impact on viewers.

Health communication is impactful when influencers and experts work together. When they don’t, public health messaging risks veering into confusion, not clarity.

Why we need influencers, but with guardrails

It’s no secret that balanced, nuanced nutrition advice rarely trends. Fear, outrage, and “shocking truths” drive engagement far faster than measured science. That’s why influencers matter: they have the reach that scientists and policymakers don’t.

Campaigns like Marcus Rashford’s push for free school meals or Jamie Oliver’s school food reforms worked because they paired influence with expertise.

Wicks and van Tulleken’s documentary, on the other hand, shows what happens when a well-intentioned message is stripped of context, especially when context is what people need most.

Where “KILLER” missed the mark

1. Fear Over Facts

The dark lab scenes, the ominous warnings, the “KILLER” label, it’s theatre, not science. While it makes for gripping television, it also fuels anxiety. Without clarity on which ingredients are harmful, in what amounts, or why, the message becomes distorted.

The phrase “dose makes the poison” may sound tedious, but it’s scientifically accurate. Context matters. Even water can be harmful in excess. A protein bar occasionally won’t harm you, but the campaign implied otherwise.

2. Oversimplifying the “UPF Problem”

The term ultra-processed is a messy one. It lumps together everything from energy drinks to baby formula, fortified cereals, and plant-based milk. Are they nutritionally equivalent? Of course not.

UPFs are a diverse group, and the current system of classification doesn’t account for nutrient content or real-world use. Many people depend on UPFs, because of medical conditions, sensory sensitivities, time, or cost. Demonising an entire category of foods risks alienating those who don’t have the privilege of choice.

That doesn’t mean our current food environment is one we should just accept though. We do have to have tough conversations, but ultimately processing level does not equal healthfulness.

The question shouldn’t be “is it processed?” but rather “what’s actually in it?” and “what else is in my diet?”

3. Ignoring the systemic barriers

For millions, the challenge isn’t confusion about ingredients, it’s access. One in five people in the UK lives in poverty. When nutritious food is unaffordable or unavailable, no amount of labelling can fix the problem.

The core issues driving poor nutrition are structural: wealth inequality, food pricing, and time poverty. Fear-based campaigns rarely acknowledge that.

4. No clear endgame

What’s the solution here? Stricter labelling? Ingredient bans? A campaign for government reform? The documentary didn’t say what the next steps are, but one can hope that there is indeed a plan.

Awareness without direction can lead to cynicism, and public health can’t afford that.

What consumers actually need

Instead of fear, people need clarity, reassurance, and tools they can use in real life:

- Focus on dietary patterns, not single foods. What you eat most of the time matters more than one meal or snack.

- Read labels for salt, sugar, saturated fat, and fibre - not just ingredient list length or processing methods

- Make swaps that suit your life, your budget, and your time. Reduce where it makes sense for you and your family.

- Let go of guilt. Balance matters more than perfection. Nutrition is personalised.

A protein bar, even one with 96 ingredients, won’t make or break your health. What matters is what you eat most of the time.

The Bigger Picture: Policy, Not Panic

If we’re serious about change, the solutions are systemic, not sensational:

- Subsidise nutritious foods so they’re affordable.

- Support reformulation to improve the quality of convenience foods.

- Implement labelling clarity and tighten the rules on misleading nutrition and health claims.

- Link nutrition policy with environmental and affordability goals.

Warning labels alone won’t transform public health, but a coordinated food systems strategy might.

The Evidence We Actually Have

The science on UPFs is still evolving. Most studies are observational, meaning they can show correlations but not cause-and-effect. What we do know, from decades of research, is this: diets rich in minimally processed, plant-forward foods support health and longevity.

That doesn’t mean cutting out convenience, it means making it work for you. Combining home-cooked meals with ready-made options can still be part of a healthy lifestyle. Perfection isn’t the goal; sustainability is.

A Missed Opportunity, But a Valuable Conversation

The “KILLER” bar may not have delivered the science it promised, but it did succeed in one important way: it got people talking. And now, the conversation needs to move beyond outrage and into action.

If influencers used their platforms to push for equitable food access, cooking education in schools, or stronger regulation on health claims - alongside nutrition experts and policymakers - that would have a transformative impact. The reach is there. The expertise exists. What’s missing is the collaboration.

Public health needs passion, but it also needs precision. Campaigns built on fear fade fast. Campaigns built on collaboration, science, and empathy endure.

Final Insight:

Food reform doesn’t start in a TV lab, it starts in our communities, our policies, and our shared commitment to understanding, not fearing, what’s on our plates.

The conversation happening right now matters - but it needs nuance, compassion, and science at the centre.

Ultra-processed foods: unpacking the myths and the real threats to our diets

We all like a clear villain. And increasingly self proclaimed health influencers are pointing the proverbial finger. In nutrition debates, ultra-processed foods (UPFs) have become the perfect target: easy to blame, easy to vilify, easy to rally against. Even Joe Wicks recently joined the conversation with his 'killer' bar. But what if we’ve been pointing our fingers in the wrong direction?

That’s not to say UPFs are harmless. But the discourse around them has become so polarized that it’s crowding out harder questions we ought to be asking.

The promise (and peril) of the UPF narrative

Over the past decade, “ultra-processed food” has become shorthand for “bad diet.” Headlines link UPFs to obesity, metabolic disease, mental health, even cancer. Yet skeptics rightly point out: the definition of “ultra-processed” is slippery, the mechanisms murky, and the evidence largely observational.

The blog at OFPlus pitches a provocative counterpoint: the obsession with UPFs may distract from more meaningful interventions. That there’s not enough clarity about what even counts as a UPF to make sweeping policy moves. And that consumer concern has outpaced scientific consensus.

I’m sympathetic to that caution. But I also think it’s worth going further: the UPF fixation can distort how we think about diets, food systems, and equity.

Simon Wright, Founder of OF+ Consulting told me:

“Books such as Ultra-Processed People have made unsubstantiated and exaggerated claims about the link between consuming UPFs and human ill-health. Social media has only intensified this frenzy, often confusing UPFs with foods high in fat, sugar, and salt (HFSS). As a result, the food manufacturing and retail sectors have come under intense scrutiny regarding how foods are formulated and promoted.

Having spent the last 40 years discussing artificial additives, I welcome the greater attention the UPF debate has brought. One positive outcome could be ingredient lists that are shorter and feature fewer odd-sounding additives. However, much of the discussion has taken on a rather hysterical tone, treating all forms of food processing as equally problematic. This is far too simplistic, and ultimately unsustainable. What’s really needed is more nuance, especially in understanding how the degree of processing affects nutrition."

When demonization does more harm than good

1. Overbroad categories drown nuance.

Under the dominant NOVA classification, many foods with vastly different nutritional profiles get lumped together. Whole grain, low-sugar breakfast cereals and industrial snack cakes might both be called “ultra-processed” even though their health impacts are not the same.

Such overgeneralization discourages reformulation. If all UPFs are suspect, then food companies will hesitate to improve salt, sugar, fiber content, or ingredient quality, even when those tweaks could benefit public health.

2. It skews attention away from systemic forces.

Focusing on UPFs shifts blame onto “bad products” rather than the systems that produce them. What about food deserts, income inequality, labor conditions, agricultural subsidies, marketing to children, and industrial consolidation? These structural issues remain under-addressed when the narrative is “avoid the processed stuff.”

3. It risks stigmatizing individuals.

People don’t eat “ultra-processed diets” by choice alone. For many, UPFs are the affordable, shelf-stable, accessible option. A rigid moral frame around “good vs bad foods” may guilt people or exacerbate shame, especially among lower-income communities.

4. Weak evidence margins get overstated.

Yes, epidemiological studies often find associations between UPF consumption and poor health outcomes. But correlation is not causation. When we don’t fully control for confounders (overall diet quality, lifestyle, socioeconomic status), we risk overinterpreting what the data show.

Even in controlled trials, isolating the effect of “processing” is tricky: changes in texture, additives, food matrix, satiety, and palatability are all entangled. We’re still parsing which features of UPFs matter most.

Also, there are considerable overlaps between UPF and HFSS foods, and these overlaps may also mask the link between health and disease outcomes and UPF.

"Overbroad categories drown nuance. Under the dominant NOVA classification, many foods with vastly different nutritional profiles get lumped together. Whole-grain low sugar breakfast cereals and industrial snack cakes might both be called “ultra-processed” even though their health impacts are not the same." - Puk Maia Holm-Søndergaard, Chief Consultant - Human Nutrition and Health Nutrition, Consumer & Analytics, Danish Agriculture & Food Council F.m.b.A

What a more balanced framing might look like

I propose a few shifts:

- From demonization to gradation. Let’s stop treating UPFs as a monolithic enemy. Some are worse than others; some may even play useful roles (e.g. shelf-stable fortified staples).

- From product focus to dietary patterns. The total diet, variety, fiber, plant-based foods, cooking, cultural foods, ultimately matters more than whether one snack is labeled “ultra-processed.”

- From individual blame to system reform. Push for policies on marketing, subsidies, labeling, food access, reformulation incentives, and corporate responsibility.

- From certainty to humility. Science evolves. Where evidence is weak or contested, policy should be cautious, transparent, and subject to revision.

A modest conclusion (with an opinion)

I don’t think we should abandon the UPF lens entirely. It has stirred real public interest, challenged complacency, and brought new questions into the nutrition conversation. But as an anchor, it’s unstable. As a moral foil, it’s too blunt. As a policy target, it’s too fuzzy.

If we keep chasing the idea that “all ultra-processed food is the problem,” we run the risk of missing the forest for the trees. We need food systems that support creativity, fairness, pleasure, and health, and that means loosening the grip on perfect villains and sharpening our focus on what actually moves the needle.

Reducing food waste vs. dietary change: which matters more for the planet?

The hidden cost of what we don’t eat

Every time food ends up in the bin, it’s not just wasted money. It’s wasted land, water, energy, and labour. Globally, about one-third of all food produced never gets eaten. If food waste were a country, it would be the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, after China and the United States.

This waste occurs throughout the supply chain, on farms, during processing, distribution, and in our homes. Retailers reject imperfect produce for cosmetic reasons, supermarkets overstock shelves, and households toss leftovers they meant to eat “tomorrow.” That “tomorrow” rarely comes.

Apps like Too Good To Go and Oddbox are part of a growing movement to intercept food before it’s wasted. Too Good To Go connects consumers with restaurants and shops that sell surplus meals at a discount, while Oddbox rescues “wonky” fruits and vegetables that supermarkets refuse. Both show how technology can turn waste into opportunity.

While apps like Too Good To Go and Oddbox help reduce waste at the retail and household level, the largest climate gains come from preventing the waste of high-impact foods — particularly meat and dairy — anywhere along the supply chain. That’s because these foods carry heavy embedded emissions from feed production, land use, and transport. Preventing food waste ensures that methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, isn’t created from the breakdown of food in landfills.

.jpg)

The environmental toll of a high-meat diet

The average Western diet relies heavily on animal products. Yet producing meat is an incredibly resource-intensive process. Livestock require huge amounts of land and water to grow their feed crops, and their digestive systems emit methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

Globally, livestock farming accounts for between 13-20% of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions—roughly the same as all transport combined. But the inefficiency goes deeper: animals convert only a fraction of the calories and protein in their feed into edible meat. By some estimates, it takes around 3 kilograms of grain to produce 1 kilogram of chicken meat, and up to 25 kilograms of grain to produce 1 kilogram of beef.

That conversion loss means a high-meat diet doesn’t just strain ecosystems; it indirectly drives massive agricultural waste. We grow vast fields of soy and maize not for people, but for livestock feed, losing most of that energy in the process. From an efficiency standpoint, the system is leaking resources at every step.

There’s also a moral dimension. Industrial farming, especially of pigs and poultry, results in the deaths of billions of animals each year, many living short and confined lives. Whether one eats meat or not, it’s hard to deny the inefficiency—and the suffering—built into such a system.

The Eat-Lancet Planetary Health Diet: a blueprint for balance

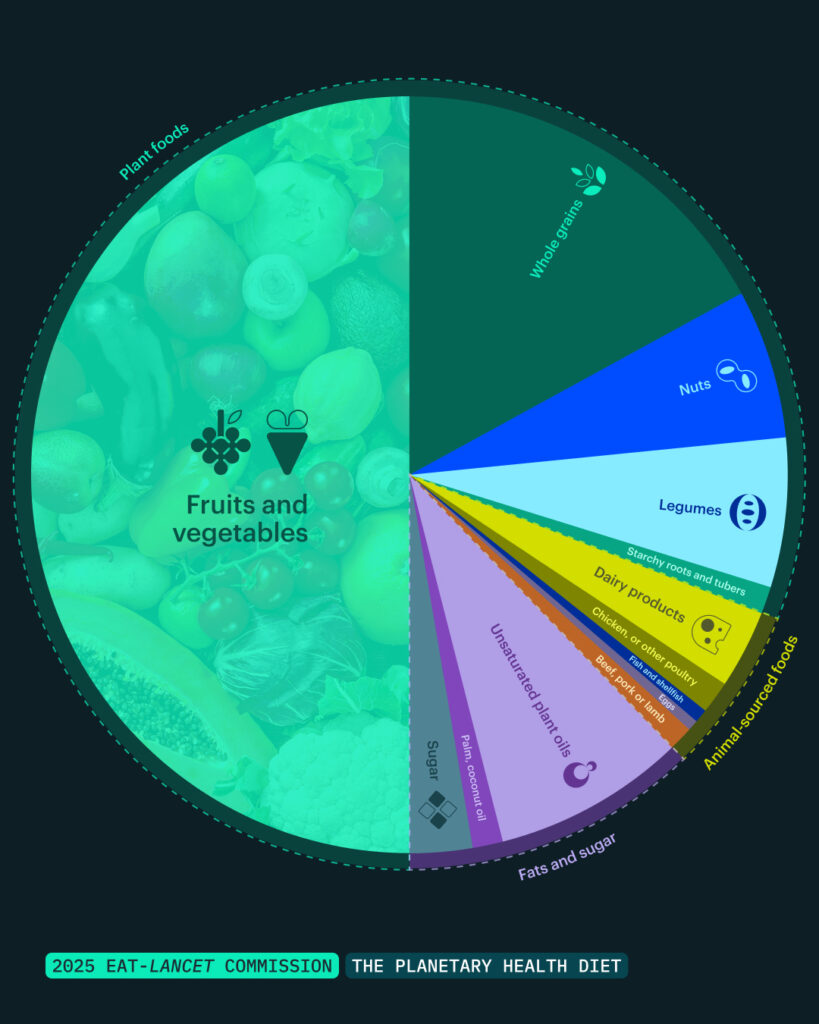

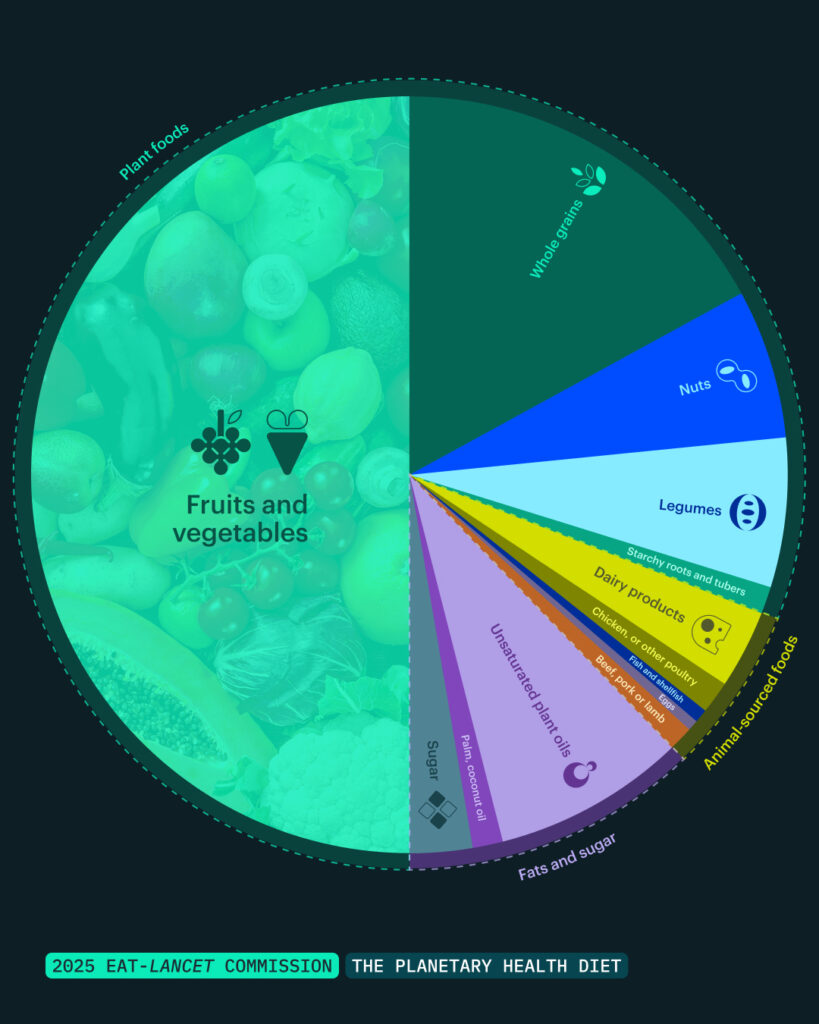

The Eat-Lancet Planetary Health Diet 2.0 provides a global framework for aligning human health with planetary limits. It isn’t about going vegan overnight. Instead, it encourages a “plant-forward” approach—more whole grains, legumes, fruits, and vegetables, and less red meat and ultra-processed foods. Find out more about the launch of the Eat-Lancet Planetary Health Diet 2.0 here.

If widely adopted, this diet could reduce global food-related greenhouse gas emissions by nearly 70%, while freeing up land and freshwater resources. It also has major health benefits, potentially preventing millions of premature deaths from diet-related diseases like heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

But the transition to such a diet is not just about personal choice. It requires systemic change: fairer subsidies, accessible plant-based options, and better support for farmers to diversify crops. Framing the shift as an evolution rather than a rejection of current habits helps make the conversation more inclusive and less polarizing.

Food waste vs. Diet: which should we prioritize?

Reducing food waste and shifting diets both tackle the same root issue: inefficiency. The first focuses on what we throw away, the second on what we choose to produce and eat.

If we only reduce food waste without changing diets, we might still perpetuate an unsustainable system that relies heavily on animal agriculture. Conversely, if we all adopted climate-friendly diets but continued wasting a third of our food, we’d miss out on enormous environmental savings.

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), eliminating food waste could cut global emissions by 8–10%. Meanwhile, dietary shifts toward the Eat-Lancet model could save even more—potentially up to 20% of total emissions—while improving health outcomes. But these aren’t competing strategies. They reinforce each other.

The social and economic ripple effects

Food waste isn’t just an environmental problem; it’s a moral one. Around 700 million people face hunger worldwide, while enough food to feed them is discarded every year. Wasting food deepens inequality by diverting resources from those who need them most.

At the same time, changing diets can improve social justice outcomes. Lower demand for feed crops could reduce land pressure in developing countries, where forests are often cleared for soy destined for animal feed. Shifting to more plant-forward diets can also make nutritious food more affordable and accessible.

Both strategies require systemic support: investment in cold chains and food storage to reduce spoilage, education campaigns about portion planning, and fairer food pricing models that don’t penalize sustainability.

Practical ways to reduce food waste

- Plan meals before shopping. Most household waste comes from buying too much. A simple list can save both money and emissions.

- Store food properly. Learn which foods need refrigeration, which don’t, and how to revive wilted greens or stale bread.

- Embrace “imperfect” produce. Support platforms like Oddbox or local markets that sell misshapen but perfectly edible fruit and vegetables.

- Use tech to your advantage. Apps like Too Good To Go and Olio help rescue surplus food from restaurants and shops.

- Compost what’s left. When waste is unavoidable, composting prevents methane emissions from landfills and returns nutrients to the soil.

Practical ways to shift diets without sacrifice

- Start small. Replace one meat-based meal per day with a plant-based alternative like lentil bolognese or bean chili.

- Explore variety. Focus on what you can add—grains, pulses, nuts, seeds—rather than what you’re “giving up.”

- Support sustainable producers. Choose foods that align with regenerative or low-impact farming practices.

- Reframe indulgence. Reserve animal products for special occasions or choose smaller portions.

- Find community. Whether it’s cooking clubs or social media groups, shared experiences make change easier and more enjoyable.

Reframing waste: the overlap between the two

Reducing meat consumption and cutting food waste are deeply intertwined. A high-meat diet inherently involves hidden waste: from the feed crops grown and discarded to the animals that never reach market weight due to disease or injury. In that sense, animal agriculture is itself a vast, systemic form of food waste.

When we talk about “reducing waste,” it’s not just about leftovers. It’s about designing a food system that values resources, animals, and people equally. That might mean eating fewer animal products, but it also means rethinking how we define abundance and success in food culture.

A shared journey, not a binary choice

Reducing food waste and shifting diets are two sides of the same coin. One tackles excess at the end of the chain, the other at its beginning. Together, they can reshape a food system that currently consumes the planet faster than it can regenerate.

We don’t have to choose between them, and we don’t have to do everything at once. The key is progress over perfection—seeing both actions as part of a shared journey toward a healthier, more climate-friendly food future.

Whether it’s saving “ugly” vegetables through an app or swapping steak for lentils once a week, every small act of awareness ripples outward. Waste less. Eat smart. And remember: the food system isn’t fixed—it’s evolving, just like us.

Why the new EAT-Lancet report matters – and why foodfacts stands behind it

The launch of the latest EAT-Lancet Commission report has the potential to mark a turning point in how we think, talk, and act on the future of food. At FoodFacts, we see this as more than another publication: it’s a blueprint for meaningful change, one that echoes our values of clarity, justice, and accountability in the food system. It’s the result of the global scientific community coming together to produce a practical, evidence-based roadmap for change.

Beyond false choice and towards equal opportunities

On social media, health advice often sounds empowering. Narratives promise that you can “take control” of your health through individual choices. But as the launch of this report highlighted today, 5.6 billion people live in environments where healthy choices are limited, difficult, or even impossible. When food systems are built around profit rather than people, “choice” becomes an illusion.

The report reframes this reality. It argues that transformation is needed so that everyone can access healthy food. To quote one speaker at the report’s launch :

“A just food system is the goal. And the way to get there.” Dr. Gunhild A. Stordalen, Co-Founder and Executive Chair of the EAT Foundation.

Science for people

Unlike systems shaped by commercial interests, this report is first and foremost about people, and for people. It offers science designed to serve everyone, adapting to every context. The focus on justice is a new component of this latest report, one that shapes its intended impact.

Why words matter

The launch began with a reminder about the power of words:

“The future of our society, indeed the future of our species, depends upon the words that we choose to use with one another.” Dr. Richard Horton, Editor-in-Chief of The Lancet

This resonates deeply with our work at FoodFacts. Our mission is to fight misinformation about food. Why? Because food affects everybody. The word ‘misinformation’ itself can lead us to think it’s only about inaccurate facts. But it’s primarily an issue of miscommunication that shapes the way we think about food and food choices, and it remains one of the biggest barriers to change. How we frame nutrition science influences trust, behaviour, and ultimately policy.

The three words that stood out from the launching of this report were choice, freedom, and of course, justice.

The Planetary Health Diet – not one size fits all

Central to the report is the Planetary Health Diet. Far from being prescriptive, it is adaptable to cultural and dietary preferences. In fact, it mirrors many traditional diets, including the Mediterranean pattern. Research shows that a global shift towards this diet could prevent 27% of premature deaths every year, and even small steps bring measurable benefits.

Crucially, this is not about dictating what individuals eat. It’s about reshaping food environments so people can make informed, healthy, and sustainable choices, something which is also at the core of our mission at FoodFacts.

Answering public concerns

On social media, concerns about being “poisoned by the food system” are prevalent. These anxieties are not always unfounded: profit often drives decisions that can undermine health. In line with this public concern, the updated report emphasises that “people deserve to live in non-toxic environments.” This is just one example highlighting how people’s concerns and the need for justice underscore the transformations promoted in this report.

A collective imperative

The launch also made one thing clear:

“Words alone won’t feed anyone.” Amina J. Mohammed, Deputy Secretary-General of the United Nations

Systemic change requires action at local, national, and global levels. Solutions will differ across contexts, but the imperative is the same: a just food system that serves people and the planet.

At FoodFacts, our mission is to tackle misinformation as part of this transformation. But every one of us can take an important step today: engage. Read the report, join the conversation, and demand accountability.

Because, as the Commission reminds us:

“We all have a lot at stake – a lot to gain, and a lot to say.” Dr. Gunhild A. Stordalen, Co-Founder and Executive Chair of the EAT Foundation.

Latest fact-checks, guides & opinion pieces

.svg)