Reducing food waste vs. dietary change: which matters more for the planet?

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

The hidden cost of what we don’t eat

Every time food ends up in the bin, it’s not just wasted money. It’s wasted land, water, energy, and labour. Globally, about one-third of all food produced never gets eaten. If food waste were a country, it would be the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, after China and the United States.

This waste occurs throughout the supply chain, on farms, during processing, distribution, and in our homes. Retailers reject imperfect produce for cosmetic reasons, supermarkets overstock shelves, and households toss leftovers they meant to eat “tomorrow.” That “tomorrow” rarely comes.

Apps like Too Good To Go and Oddbox are part of a growing movement to intercept food before it’s wasted. Too Good To Go connects consumers with restaurants and shops that sell surplus meals at a discount, while Oddbox rescues “wonky” fruits and vegetables that supermarkets refuse. Both show how technology can turn waste into opportunity.

While apps like Too Good To Go and Oddbox help reduce waste at the retail and household level, the largest climate gains come from preventing the waste of high-impact foods — particularly meat and dairy — anywhere along the supply chain. That’s because these foods carry heavy embedded emissions from feed production, land use, and transport. Preventing food waste ensures that methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, isn’t created from the breakdown of food in landfills.

.jpg)

The environmental toll of a high-meat diet

The average Western diet relies heavily on animal products. Yet producing meat is an incredibly resource-intensive process. Livestock require huge amounts of land and water to grow their feed crops, and their digestive systems emit methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

Globally, livestock farming accounts for between 13-20% of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions—roughly the same as all transport combined. But the inefficiency goes deeper: animals convert only a fraction of the calories and protein in their feed into edible meat. By some estimates, it takes around 3 kilograms of grain to produce 1 kilogram of chicken meat, and up to 25 kilograms of grain to produce 1 kilogram of beef.

That conversion loss means a high-meat diet doesn’t just strain ecosystems; it indirectly drives massive agricultural waste. We grow vast fields of soy and maize not for people, but for livestock feed, losing most of that energy in the process. From an efficiency standpoint, the system is leaking resources at every step.

There’s also a moral dimension. Industrial farming, especially of pigs and poultry, results in the deaths of billions of animals each year, many living short and confined lives. Whether one eats meat or not, it’s hard to deny the inefficiency—and the suffering—built into such a system.

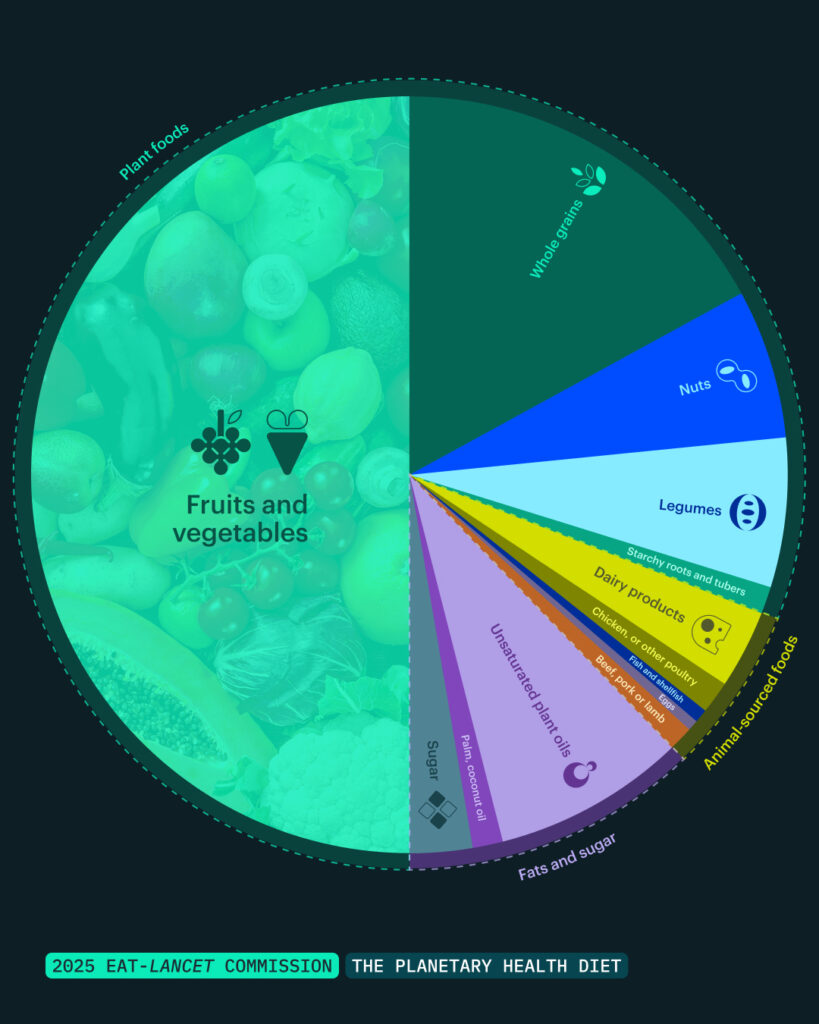

The Eat-Lancet Planetary Health Diet: a blueprint for balance

The Eat-Lancet Planetary Health Diet 2.0 provides a global framework for aligning human health with planetary limits. It isn’t about going vegan overnight. Instead, it encourages a “plant-forward” approach—more whole grains, legumes, fruits, and vegetables, and less red meat and ultra-processed foods. Find out more about the launch of the Eat-Lancet Planetary Health Diet 2.0 here.

If widely adopted, this diet could reduce global food-related greenhouse gas emissions by nearly 70%, while freeing up land and freshwater resources. It also has major health benefits, potentially preventing millions of premature deaths from diet-related diseases like heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

But the transition to such a diet is not just about personal choice. It requires systemic change: fairer subsidies, accessible plant-based options, and better support for farmers to diversify crops. Framing the shift as an evolution rather than a rejection of current habits helps make the conversation more inclusive and less polarizing.

Food waste vs. Diet: which should we prioritize?

Reducing food waste and shifting diets both tackle the same root issue: inefficiency. The first focuses on what we throw away, the second on what we choose to produce and eat.

If we only reduce food waste without changing diets, we might still perpetuate an unsustainable system that relies heavily on animal agriculture. Conversely, if we all adopted climate-friendly diets but continued wasting a third of our food, we’d miss out on enormous environmental savings.

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), eliminating food waste could cut global emissions by 8–10%. Meanwhile, dietary shifts toward the Eat-Lancet model could save even more—potentially up to 20% of total emissions—while improving health outcomes. But these aren’t competing strategies. They reinforce each other.

The social and economic ripple effects

Food waste isn’t just an environmental problem; it’s a moral one. Around 700 million people face hunger worldwide, while enough food to feed them is discarded every year. Wasting food deepens inequality by diverting resources from those who need them most.

At the same time, changing diets can improve social justice outcomes. Lower demand for feed crops could reduce land pressure in developing countries, where forests are often cleared for soy destined for animal feed. Shifting to more plant-forward diets can also make nutritious food more affordable and accessible.

Both strategies require systemic support: investment in cold chains and food storage to reduce spoilage, education campaigns about portion planning, and fairer food pricing models that don’t penalize sustainability.

Practical ways to reduce food waste

- Plan meals before shopping. Most household waste comes from buying too much. A simple list can save both money and emissions.

- Store food properly. Learn which foods need refrigeration, which don’t, and how to revive wilted greens or stale bread.

- Embrace “imperfect” produce. Support platforms like Oddbox or local markets that sell misshapen but perfectly edible fruit and vegetables.

- Use tech to your advantage. Apps like Too Good To Go and Olio help rescue surplus food from restaurants and shops.

- Compost what’s left. When waste is unavoidable, composting prevents methane emissions from landfills and returns nutrients to the soil.

Practical ways to shift diets without sacrifice

- Start small. Replace one meat-based meal per day with a plant-based alternative like lentil bolognese or bean chili.

- Explore variety. Focus on what you can add—grains, pulses, nuts, seeds—rather than what you’re “giving up.”

- Support sustainable producers. Choose foods that align with regenerative or low-impact farming practices.

- Reframe indulgence. Reserve animal products for special occasions or choose smaller portions.

- Find community. Whether it’s cooking clubs or social media groups, shared experiences make change easier and more enjoyable.

Reframing waste: the overlap between the two

Reducing meat consumption and cutting food waste are deeply intertwined. A high-meat diet inherently involves hidden waste: from the feed crops grown and discarded to the animals that never reach market weight due to disease or injury. In that sense, animal agriculture is itself a vast, systemic form of food waste.

When we talk about “reducing waste,” it’s not just about leftovers. It’s about designing a food system that values resources, animals, and people equally. That might mean eating fewer animal products, but it also means rethinking how we define abundance and success in food culture.

A shared journey, not a binary choice

Reducing food waste and shifting diets are two sides of the same coin. One tackles excess at the end of the chain, the other at its beginning. Together, they can reshape a food system that currently consumes the planet faster than it can regenerate.

We don’t have to choose between them, and we don’t have to do everything at once. The key is progress over perfection—seeing both actions as part of a shared journey toward a healthier, more climate-friendly food future.

Whether it’s saving “ugly” vegetables through an app or swapping steak for lentils once a week, every small act of awareness ripples outward. Waste less. Eat smart. And remember: the food system isn’t fixed—it’s evolving, just like us.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources

- Alexander et al. (2016). Human appropriation of land for food: the role of diet. Global Environmental Change.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. 2025. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2025 – Addressing high food price inflation for food security and nutrition. Rome.

- Green Queen (3 October 2025). Richest 30% Drive 70% of Food Climate Costs: Eat-Lancet 2.0

- Hannah Ritchie (2020). “Food waste is responsible for 6% of global greenhouse gas emissions” Published online at OurWorldinData.org.

- The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy, sustainable, and just food systems. Rockström, Johan et al. The Lancet, Volume 406, Issue 10512, 1625 - 1700

- The Guardian (13 September 2021). Meat accounts for nearly 60% of all greenhouse gases from food production, study finds

- UNCC (30 September 2024). Food loss and waste account for 8-10% of annual global greenhouse gas emissions; cost USD 1 trillion annually

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)