‘Game changer’ or gimmick: a deep dive into alkaline and low PRAL diets

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

A recent article by Meike Leonard of the Daily Mail claimed there may be more to the alkaline diet than we first thought. The article highlights a new study and goes on to suggest that alkaline foods could ‘slash health risks’ such as osteoporosis, type 2 diabetes and kidney disease as well as ‘lower stress levels and help shed excess fat’. But is this new evidence really a ‘game changer’? Let’s take a further look at what the science has to say.

Low-PRAL diets can indeed be a useful intervention, especially for those with chronic kidney disease and kidney stones, and some studies suggest they may be beneficial for other chronic diseases as well. However, for the general healthy population, the research is still limited and more evidence is needed to truly understand the science.

For now, the fundamentals of a healthy diet remain the same, with a key focus always being on whole foods, lots of fruits and vegetables and of course balance.

Framing low-PRAL diets as a “modern version” of the alkaline diet risks spreading confusion and encouraging unnecessary food restrictions. Bold, sweeping statements online can sound appealing, but in reality there is no silver bullet for health and nutrition.

Following overly restrictive diets that are not properly backed by research, or guided by the help of a healthcare professional, could do more harm than good and make healthy eating unnecessarily confusing and difficult.

Be cautious of sweeping statements online. This article uses serious sounding medical terms without clearly explaining what they mean or how strong the evidence is. This lack of context can be misleading and often exaggerate the real risk.

A note on pH

What is pH?

Before analysing the article’s claims further, it is important to understand some of the key terms used throughout the article, and put them into context.

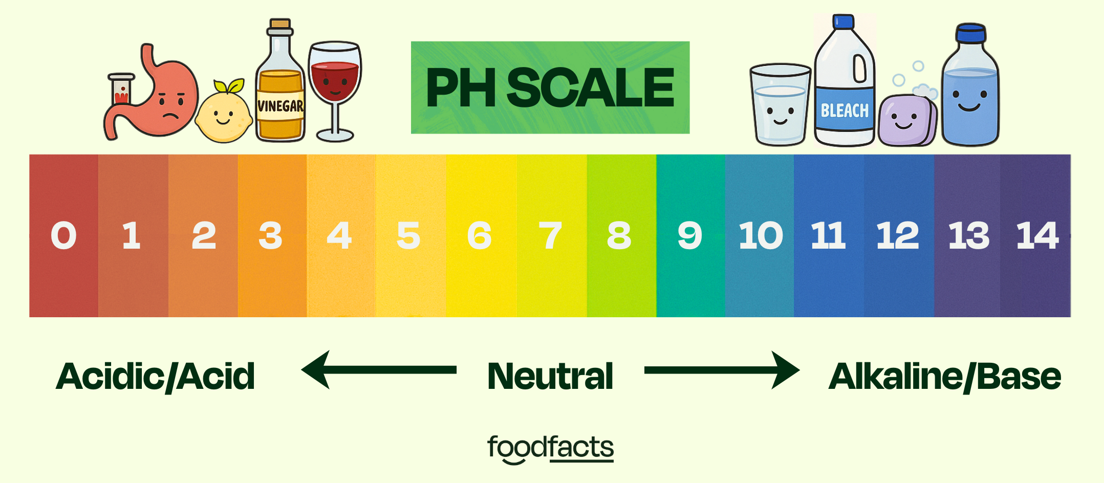

pH: In scientific terms pH is a measure of hydrogen ions in a solution. In layman’s terms it is a way of measuring how acidic or alkaline a liquid is.

pH is measured on a scale that runs from 0-14.

Acidic/Acid: This refers to a substance with a pH below 7. For example, stomach acid, lemon juice and vinegar are all acidic.

Alkaline/Base: This refers to a substance with a pH above 7. For example, baking soda, soap and bleach are all alkaline.

Neutral: This refers to a substance with a pH of 7. It is neither acidic or alkaline. For example, pure water.

Why does pH matter in the body?

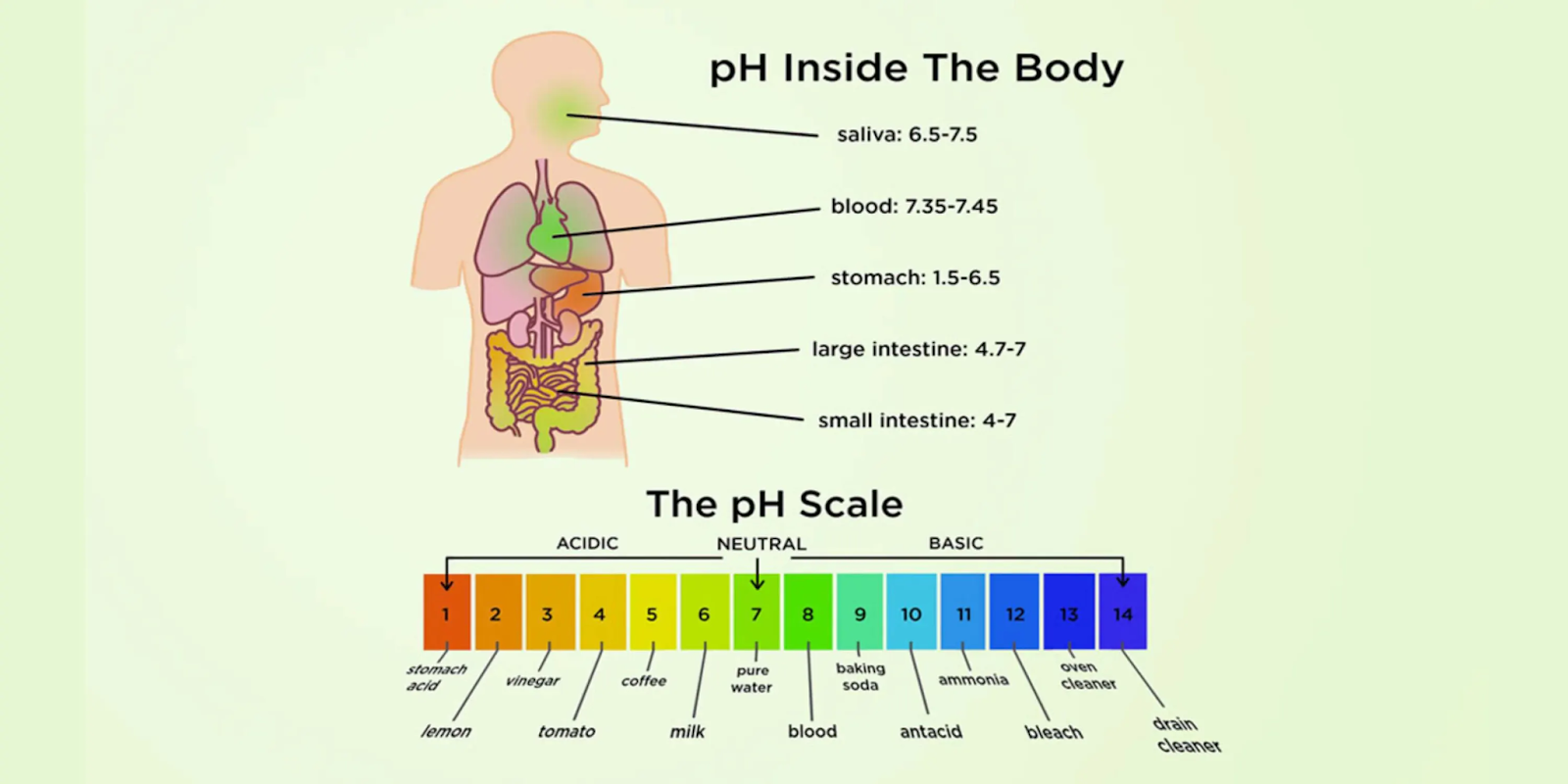

The body has tight mechanisms in place to maintain pH homeostasis (or pH balance). Certain areas in the body depend on having the correct pH. For example, blood pH must be maintained in a very narrow range of 7.35-7.45. If blood pH moves too far out of this range, it can cause acidosis (too acidic) or alkalosis (too alkaline). Both of these can be dangerous, and in extreme changes of pH even cause death, due to the effect on certain proteins and enzymes needed for vital bodily functions.

The alkaline diet: a quick history

Originally, the alkaline diet claimed to alter the body’s pH depending on the food that you ate. It emphasised so-called ‘alkaline foods’ such as fresh fruits and vegetables, nuts, seeds and plant proteins while limiting so-called ‘acidic foods’ such as meat, dairy, processed cereals, and refined sugars. This change in body pH was claimed to improve overall health and prevent a number of diseases.

However, this classification of ‘acidic’ and ‘alkaline’ foods was inconsistent and largely inaccurate. For example some processed foods, such as canned or frozen vegetables and beans are not necessarily acidic, even though the diet categorised them as such.

Due to these inconsistencies, and the fact that the body’s pH is tightly regulated, the initial proposition of an alkaline diet was quickly dismissed by scientists and healthcare professionals alike. The idea of altering the body’s pH was simply impossible and it was assumed that any potential benefits were due to the removal of ultra-processed foods, sugar or caffeine and an increase in fruits and vegetables.

But does this new research pose a different story or has this fad just had a rebrand?

Claim 1: “The modern approach is based on a measurable concept, called potential renal acid load, or PRAL…. This estimates the amount of acid the kidneys must excrete after food…”

Fact-check: The information provided on PRAL is mostly accurate, however the article implies low PRAL diets are a new science-backed version of the alkaline diet. This is misleading, as the two are actually distinctly different concepts.

So what is PRAL?

As discussed above, the body has tight mechanisms in place to control blood pH and ensure correct bodily functions. One of these mechanisms is via the kidneys (the other main mechanism is via the lungs).

The kidneys help regulate blood pH by filtering out excess acids or bases through the urine. They do this by reabsorbing bicarbonate (a base) and excreting hydrogen ions (an acid), helping to keep the blood’s pH tightly regulated.

Potential renal acid load (PRAL) refers to this process and how much acid is excreted by the kidneys after breaking down food.

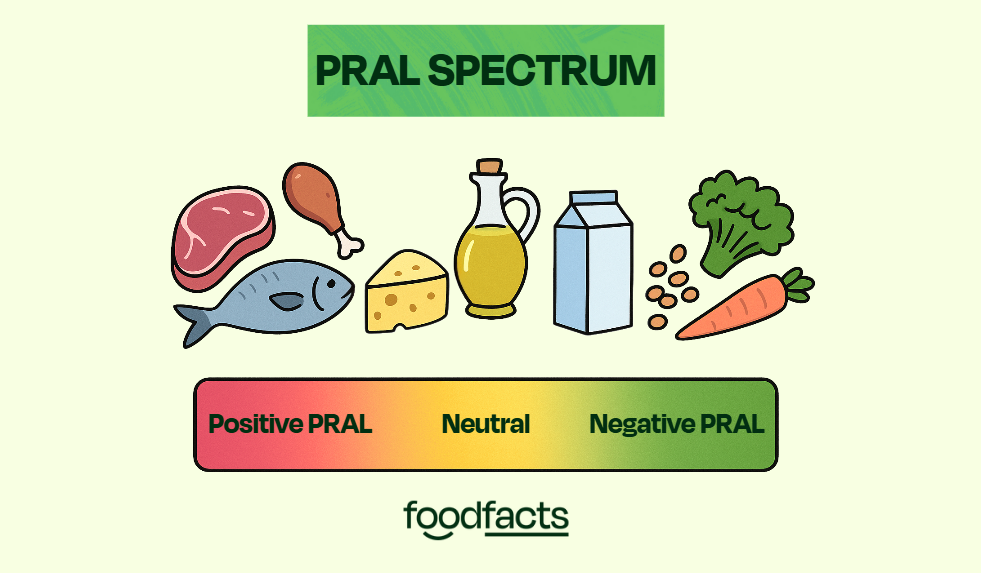

-Positive PRAL foods contain more acid-producing nutrients such as protein and phosphorus and therefore increase net acid excretion. Examples include meat, poultry, fish, seafood and cheese.

-Negative PRAL foods contain base-producing nutrients such as potassium, magnesium, and calcium. Examples include fruits, vegetables and some beans, nuts and legumes.

It is important to note that unlike the alkaline diet, PRAL does not reflect blood pH, which in healthy individuals always remains in that 7.35-7.45pH range. It instead is an indication of how hard the kidneys are working to maintain blood pH (source).

While the explanation of PRAL in the article is largely correct, describing this as a ‘modern approach’ to the alkaline diet may unintentionally imply that high- and low-PRAL diets alter blood pH which, as previously discussed, is not the case in healthy individuals.

Claim 2: “It’s the long-term build-up of these by-products (sulphuric/phosphoric acid), researchers believe, that may contribute to chronic disease…’

Fact-check: There are some studies that show links between high-PRAL diets and certain chronic diseases. This is an interesting topic to watch, but for now, more research is needed to confirm these associations and understand the mechanisms behind them.

The wording here is slightly misleading as the acid by-products do not necessarily ‘build up’ in the body. As previously established the pH levels in the body are tightly regulated by the kidneys and lungs on a minute-to-minute and daily basis.

However there is research to suggest that continually high-PRAL diets may cause low grade metabolic acidosis. This is when the body’s pH shifts slightly towards acidic (aka closer to a pH of 7.35) and it has been linked to some chronic diseases, such as osteoporosis, type 2 diabetes, kidney stones and chronic kidney disease (source).

Is there evidence that positive/high-PRAL diets cause chronic disease?

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a condition that causes weakening of bones, leading to increased risk of fractures and breaks.

There is evidence that a high- PRAL diet may contribute to osteoporosis. For example, a systematic review and meta analysis found that higher dietary acid load is significantly associated with increased fracture risk. In higher quality studies specifically, there was a 12% higher risk of fractures.

This is likely due to low grade metabolic acidosis caused by high-PRAL diets. In order to neutralise the acid, bones will release calcium and other minerals which over time, weakens them, making them more prone to fractures.

Type 2 Diabetes

Type 2 Diabetes occurs when the body cannot use insulin correctly. Insulin is a hormone that helps cells take up glucose to use for energy, so this condition results in high blood sugar levels.

Another systematic review and dose-response meta analysis looked at 7 long-term studies. For every 5-point increase in PRAL there was a 4% higher risk of type 2 diabetes. Interestingly, this risk followed a U-shape, suggesting that both very low and very high PRAL diets may carry risk.

The authors speculated that this may occur because the body has shifted slightly to a more acidic state (low-grade metabolic acidosis). As a result less insulin is released by the pancreas and the insulin that is released works less effectively (also known as insulin resistance), and blood pressure also increases. Sugar therefore stays in the blood and blood sugar levels remain elevated.

Kidney Stones

Kidney Stones form in the kidneys when substances such as calcium, oxalate, or uric acid become too saturated in the urine and they form a stone. More acidic urine makes it easier for uric acid and calcium oxalate kidney stones to form. The higher PRAL diet you eat, the more acid your kidneys have to get rid of, making your urine more acidic. For this reason, eating a more alkaline producing diet is often a strategy to prevent kidney stones for people with high urine levels of acid or calcium, as well as low citrate. Citrate is an alkaline molecule that makes it harder for calcium kidney stones to form. A lower PRAL diet will promote the excretion of citrate in urine.

One study found associations between high-PRAL diets and the formation of calcium oxalate kidney stones.

Here we get a glimpse of how nuanced and interconnected the systems of the body really are, as it is the release of calcium from bones (as mentioned above in regards to osteoporosis) which leads to increased calcium in urine that could be one of the mechanisms behind this association.

Chronic kidney disease

Chronic kidney disease is a condition where the kidneys are less able to filter waste and excess fluid from the blood. A meta analysis of 23 studies examined the association between high-PRAL diets and chronic kidney disease. They found that people with a higher dietary acid load had a 31% increased risk of developing chronic kidney disease.

Mechanisms again are related to the low grade metabolic acidosis caused by high-PRAL diets. This shift towards a more acidic state can cause release of endothelin, a substance that in normal levels helps regulate circulation but in high levels can damage the kidneys over time. There can also be increases in the hormone aldosterone which can raise blood pressure, further contributing to kidney disease.

Often low-PRAL diets are recommended by healthcare professionals as a way to prevent and treat acidosis in those with chronic kidney disease.

Low-PRAL diets also help to control blood glucose and blood pressure, the leading causes of chronic kidney disease. So controlling these factors will in turn help to protect the kidneys. Again we see here how all these mechanisms can overlap and work alongside each other to contribute to overall health.

Bottom line

While the essence of this claim is accurate, emphasis on the word ‘may’ is needed.

The processes described above are complex. This research is promising, but while it can give us some useful insight, further studies are needed to confirm these findings and to give us a clearer picture of the processes taking place behind these observations. Melanie Betz is a Registered Dietitian specialising in kidney stones and Chronic Kidney Disease. She highlights the importance of small changes over an all-or-nothing mindset, a common pitfall when complex research is taken out of context:

“It is important to think about this on a spectrum - VERY high PRAL is likely not good - but just lowering it (not necessarily to a NEGATIVE number) is likely going to be beneficial for health.

To truly have a negative PRAL diet - you'd likely need to be nearly 100% vegetarian/vegan.“

Claim 3: ‘‘The more alkaline (negative-PRAL) foods you eat, the easier it is for the body to lose weight,… Low-fat, vegan foods can help reduce the risk of diabetes, lower stress levels and help shed excess fat, without muscle-loss.”

Fact-check: This claim is based on one single study with clear confounding variables. Before giving dietary advice for the general population, it is important to have consistent evidence from multiple large scale, long-term studies.

The claims made are based on a recent study that compared a low-fat vegan diet with a Mediterranean Diet. The study found that a low-fat vegan diet had lower PRAL, and there was an association between this lower PRAL and increased weight loss.

However there are a couple of important aspects of the study to consider:

A low-fat vegan diet and Mediterranean Diet are both considered lower in PRAL than a standard Western diet. Therefore comparing them may not be the best way to measure the effect of low-PRAL diets.

Additionally, as fats have a higher calorie density, it is likely that the low-fat vegan diet was lower in calories than a Mediterranean Diet which has a high focus on nuts, seeds, olive oil and oily fish - foods that are higher in healthy fats and thus higher in calories.

Here we must remember the difference between correlation and causation. Just because there was a correlation between the lower PRAL, low-fat vegan diet and weight loss, does not mean that it was low PRAL that caused the weight loss. In this case there is a clear confounding variable: the difference in calories.

In other studies, Mediterranean Diets have also been shown to be beneficial, particularly for sustainable weight loss (source), so there is clearly more at play here.

Did participants lose weight because the foods were low in PRAL, or because low-PRAL foods mainly consist of fruits, vegetables, and legumes? These foods are already known to be low in calories, high in water and fibre, rich in beneficial nutrients and phytochemicals, and overall linked to better health outcomes and weight loss.

When thinking of general nutrition advice, the key is that it should be applicable to everyone and backed by concrete research. There are many aspects to consider when creating public health and dietary guidelines. In this case larger, long-term studies, with more direct measurements of PRAL and energy intake are needed to confirm if these weight loss claims are really due to lower PRAL or not. While one study alone may provide helpful information and inspire future research, it is not enough evidence to give advice to the general population. Melanie Betz questions whether this new way of categorising foods as either 'good' or 'bad' depending on their PRAL value is helpful for consumers, or whether it might do more harm than good:

"A lower PRAL diet will include more foods that we know are good for you like fruits, veggies and plant proteins. It is no secret that this is good for chronic disease prevention and overall health. However, I don't think that adding yet an EXTRA thing for people to be concerned about is going to help when making food choices.

From a scientific perspective, it is certainly an interesting line of study. But from a public health standpoint, do we really need another way to categorise foods as "good" or "bad"? It is also important to note that some very healthful foods do have a positive PRAL value (like whole grains), so I fear this categorisation would demonise them. Likewise, fats are always neutral, so by focusing on ALL "negative" PRAL foods, we would end up cutting out healthy fats like olive oil."

Claim 4: “Eating acidic foods triggers the release of stress hormone cortisol, which is needed to process and digest the meal, and the body has to work harder to regulate it causing cortisol to spike even further. High levels of cortisol have been shown to disrupt metabolism, increase appetite and promote fat storage, particularly in the stomach.”

Fact-check: Here again it is the wording that makes this claim slightly misleading; suggesting that this is established evidence while not making clear that more research is needed to confirm associations.

We know that consistently high PRAL diets can cause low grade metabolic acidosis. One of the body’s responses to this is release of the hormone cortisol. Cortisol has a number of functions but in this case it breaks down muscle proteins into amino acids (the building blocks of proteins) that the body can convert to bicarbonate (a base) which neutralises excess acid. Cortisol also increases the removal of acid by the kidneys. However it is important to note that this cortisol release is a response to maintain acid-base balance, not specifically to process or digest the meal.

There is less evidence to support ‘acidic foods’ ‘disrupt(ing) metabolism’. As most studies are observational, it comes back to correlation vs causation. We do not yet have concrete evidence to support direct causation. Similarly to the previous claim, is it that acidic foods directly increase cortisol that impacts metabolism? Or are there other factors at play such as overall diet or calorie intake? More research is needed to know for sure.

Overall, this claim is partly supported but lacking in nuance and evidence. Melanie Betz emphasises that balance is key:

PRAL isn't about individual “acidic foods” - it is about the overall BALANCE of your diet. Eating high PRAL steak is probably FINE if you aren't eating a giant portion and balance it with more alkaline producing foods like a potato and asparagus. Like so many fad diets, this scientific truth ("certain foods produce acid/aklai") is taken too far and used to inappropriately demonize foods. Like SO many things in nutrition, it is crucial to look at entire dietary PATTERNS and not individual "good" or "bad" foods.

Is this diet really a game changer? … Probably not in the ways the article suggests.

The Daily Mail’s claims promise quick fixes: “better than weight loss jabs”, “burn fat fast”, “slash your health risks”and “no side effects”. These are based largely on a single study with little explanation of the mechanisms or limitations behind the findings. As is often the case, the reality is far more nuanced.

The statements in the article aren’t entirely false, but the implication that the long-debunked alkaline diet is now supported by science is misleading. Low-PRAL diets are not a new or updated version of the alkaline diet. Rather, potential renal acid load (PRAL) is a well-established concept in physiology that reflects how the kidneys maintain acid–base balance. While there are overlaps in the types of foods encouraged (fruits, vegetables, legumes) and the involvement of pH, equating the two oversimplifies and confuses the science.

Do we need to worry about PRAL?

There indeed may be benefits to a low-PRAL diet, particularly, for those with Chronic Kidney Disease and those prone to oxalate or uric acid kidney stones with certain urine risk factors. However, for healthy individuals, pursuit of an overly restrictive ‘low-PRAL’ or ‘alkaline’ diet may lead to unnecessary food rules, potential nutrient deficiencies, and in worst cases, disordered eating patterns. As always, any dietary changes should always be guided and overseen by a dietitian to ensure they are carried out properly and safely.

Processes in the body are complex and nutrition science rarely offers black-and-white answers. This emerging research is interesting, but what it really points to is the need for more research. High-quality, long-term studies are needed to confirm these associations and clarify underlying mechanisms.

The bottom line:

What we do know with confidence is that diets rich in fruits, vegetables, and legumes - all naturally lower in PRAL - are associated with better overall health outcomes. Whether those benefits stem from a reduced acid load, higher nutrient density, or increased fibre and phytochemicals (or all of the above) remains to be seen.

In the meantime, this line of research doesn’t really change the fundamentals of healthy eating. The most evidence-backed advice remains the same: Eat a balanced diet based on mostly whole foods, with plenty of fruits, vegetables, and plant-based proteins, while limiting processed foods, added sugars, and excessive meat intake.

Alkaline or not, the key to good nutrition, as the article concedes, is balance.

We have contacted the Daily Mail and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources

Melanie Betz MS, RD, CRS, CSG (2022). What Is PRAL & How Does It Affect Kidneys?

I.A. Osuna-Padilla (2019). Dietary acid load: Mechanisms and evidence of its health repercussions.

Mirzababaei, A., Daneshvar, M., Basirat, V., Asbaghi, O. and Daneshzad, E. (2025). Association between dietary acid load and risk of osteoporotic fractures in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies.

Jayedi, A. and Shab-Bidar, S. (2018). Dietary acid load and risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of prospective observational studies.

Haghighatdoost, F., Sadeghian, R., Clark, C.C.T. and Abbasi, B. (2020). Higher Dietary Acid Load Is Associated With an Increased Risk of Calcium Oxalate Kidney Stones.

Mofrad, M.D., Daneshzad, E. and Azadbakht, L. (2019). Dietary acid load, kidney function and risk of Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies.

Kahleova, H., Maracine, C., Himmelfarb, J., Jayaraman, A., Znayenko-Miller, T., Holubkov, R. and Barnard, N.D. (2025). Dietary acid load on the Mediterranean and a vegan diet: a secondary analysis of a randomized, cross-over trial.

Mancini, J.G., Filion, K.B., Atallah, R. and Eisenberg, M.J. (2016). Systematic Review of the Mediterranean Diet for Long-Term Weight Loss.

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)