Garlic and blood pressure: what the evidence shows and what it doesn’t

The problem with single-food narratives

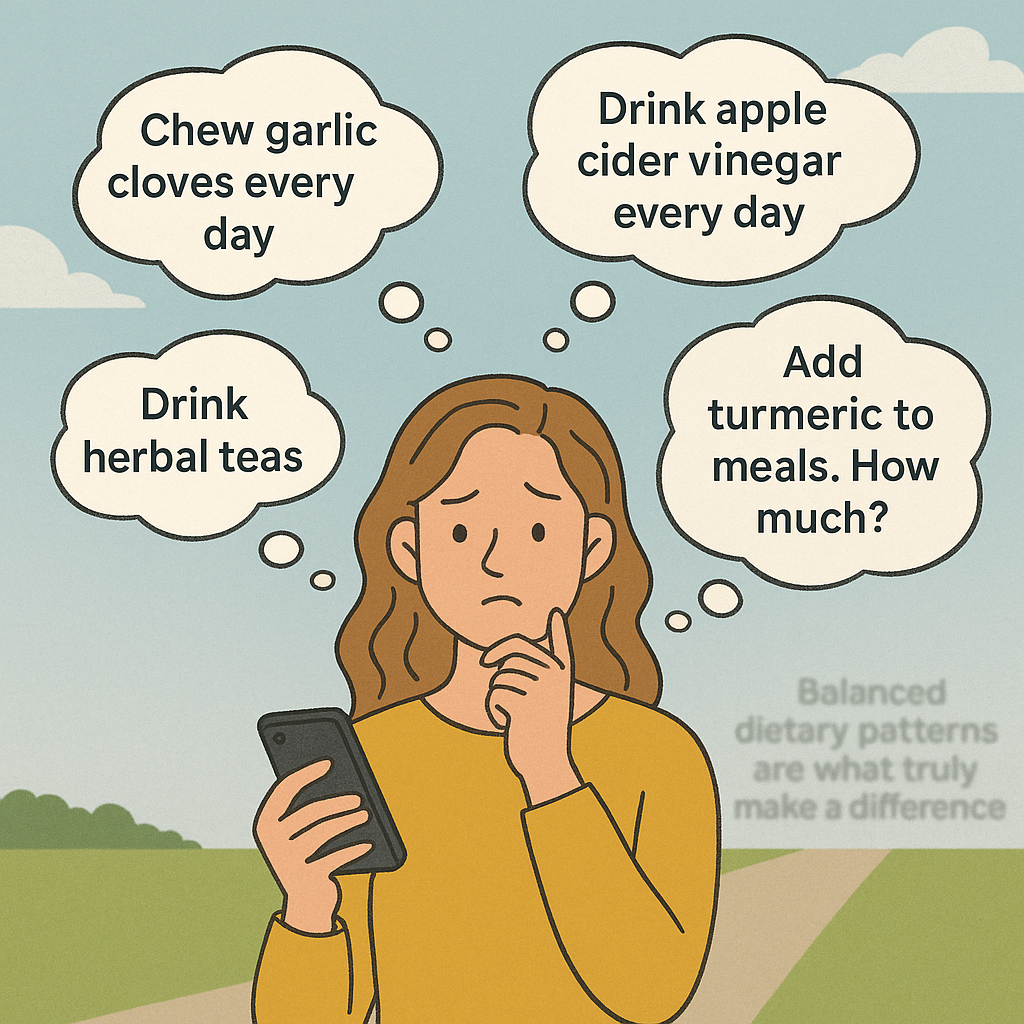

It is absolutely true that lifestyle changes can meaningfully reduce blood pressure. But regularly focusing on single ingredients distorts the picture of how nutrition works. Social media thrives on spotlighting one miracle food at a time: garlic today, turmeric tomorrow, lemon water the next day. This can turn nutrition into a never-ending checklist of daily ‘rituals’. Should you eat two raw garlic cloves every morning? Add turmeric to every meal? Brew endless herbal teas? For a lot of people this becomes overwhelming, distracting from what actually works. This is generally evident in the comments section of such posts, where people are often seeking clarification as to how to incorporate these foods into their diet to make a practical difference.

What research consistently shows is that long-term health depends on overall patterns: diets rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains and fibre, while limiting saturated fats, processed foods, and excess sugar.

The supplement contradiction

There is also a contradiction worth noting. Many influencers who warn against “Big Pharma” promote supplements as a solution to many health-related problems. Yet it is important to remind the public that supplements are less regulated than medicines. Their purity, dosage, and claims are not always tested to the same standard.

In the U.S., supplements fall under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA), which allows products to be sold without FDA pre-approval as long as they don’t claim to treat disease. In Europe, garlic supplements are classified as food supplements under the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), which authorises only generic claims like “maintenance of heart health.”

Clinically studied products such as Kyolic Aged Garlic Extract stand out because they use standardised preparations containing S-allylcysteine, the same compound linked to garlic’s cardiovascular benefits (source). But many retail supplements vary widely in potency, making consistency, effectiveness and safety uncertain.

Beyond this fact-check: the big picture

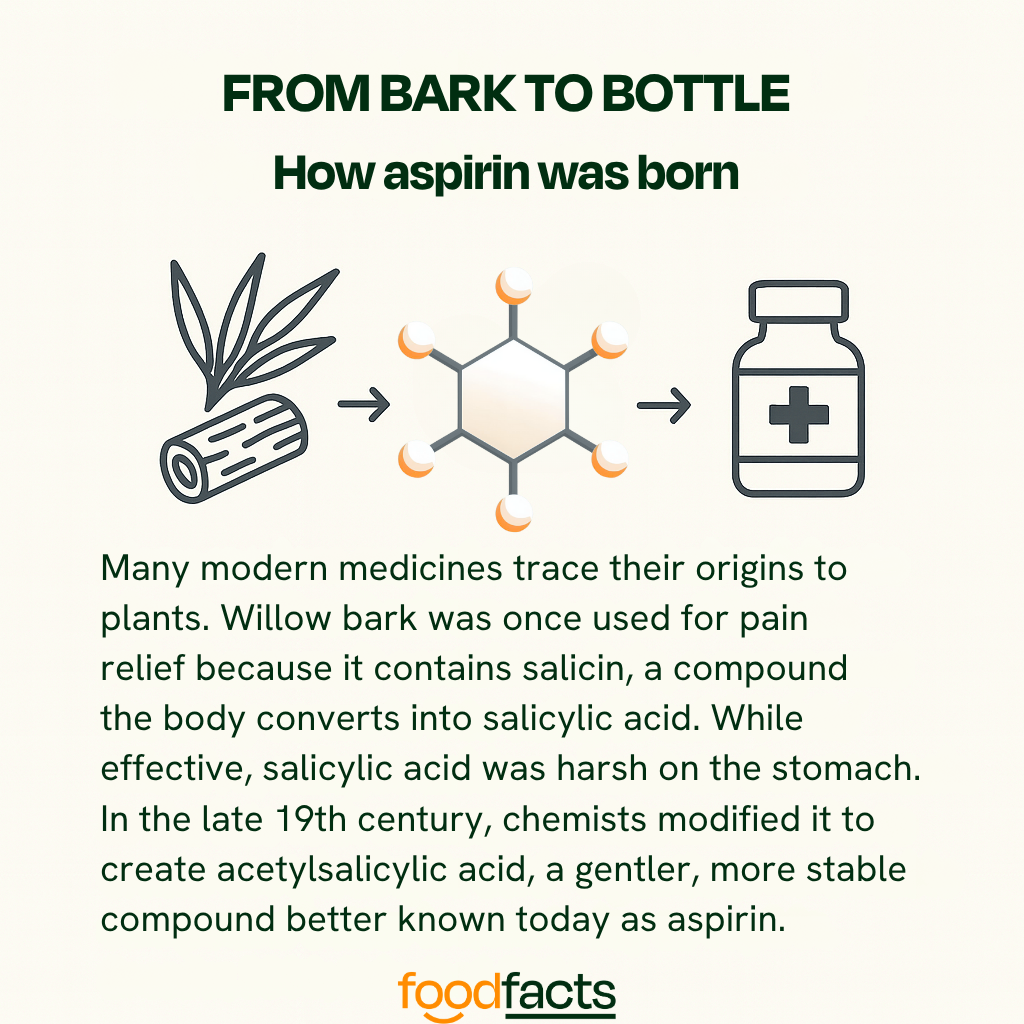

As with all nutrition questions, balance matters. Without it, nutrition advice can slip into rigid rules that overpraise or demonise foods, missing the broader dietary patterns that truly support long-term health. Understanding how these processes work, how foods interact with biological systems, and how natural compounds can inspire medical treatments, is essential for making informed, evidence-based decisions.

Promoting healthy foods is important, because diet plays a central role in preventing disease and supporting overall well-being. But it’s equally important to recognise that food alone cannot always correct complex conditions once they develop. Medical treatments often build on nature’s chemistry, refining it to create safe, consistent, and targeted therapies. This is a principle that extends far beyond garlic, and far beyond this fact-check, as this final example illustrates:

Final take away

Enjoy garlic as part of your diet, but don’t rely on it to replace prescribed blood-thinning medication. Instead of seeing it as food versus medicine, it’s more accurate, and empowering, to see them working together.

We have contacted Eric Berg, D.C. and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Why the message misleads

Logic leap: can food replace drugs?

Issues arise from the suggestion that garlic can replace drugs altogether. Indeed the post does not just boast the benefits of garlic. It suggests that pharmaceutical drugs merely mimic the effects of food, appealing to the message that ‘you don’t need medication if you eat the right foods’, which is prevalent on social media. This idea sounds empowering, but it also oversimplifies a complex reality. High blood pressure often involves multiple underlying processes, and while garlic may support its management, other interventions and treatments should be acknowledged too. Check out our guide for spotting misused research on social media.

A recent review on garlic and hypertension puts it clearly: “while garlic may offer benefits, it should not be considered a substitute for conventional medications.” The same review notes that many patients with hypertension already distrust drugs, turning instead to herbal remedies. In this context, posts like this risk deepening that distrust, possibly nudging people away from treatments whose efficacy has been proven to significantly reduce the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

Garlic does influence nitric oxide and hydrogen sulphide pathways, relaxing blood vessels and reducing platelet stickiness (source). But its effects depend on how the garlic is grown, stored, prepared, and digested: variables that make allicin content unpredictable. Genetics and nutrient status can also influence how effectively the body converts garlic’s compounds into the molecules that help regulate blood pressure, so individual responses may vary. This is important, because it means that for some people, supportive nutrition and lifestyle habits might not be enough to effectively manage blood pressure. As British Heart Foundation dietitian Victoria Taylor notes, while garlic is associated with cardiovascular effects, there is “not much hard evidence” that eating cloves alone can deliver consistent therapeutic outcomes (source).

Medications are developed to isolate a mechanism, deliver controlled doses, and produce reproducible results across patients, essential qualities for managing high-risk conditions like hypertension.

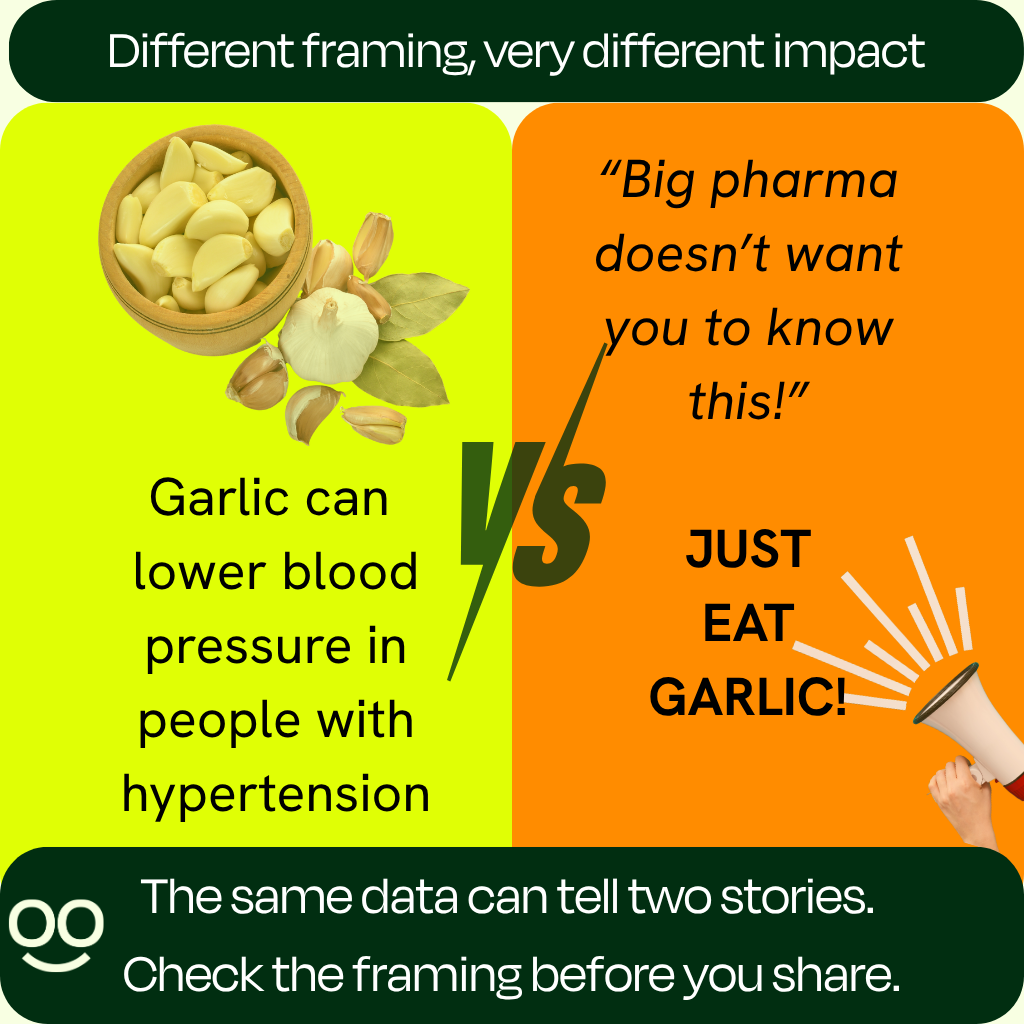

Packaging that fuels distrust

The framing of posts like Eric Berg’s feeds a familiar narrative: that “Big Pharma” hides nature’s cures to sell synthetic alternatives. This framing resonates emotionally because it offers both control and simplicity: food feels familiar, while pharmaceuticals aren’t, and they generate profit. But this creates a false dichotomy.

Take the World Health Organisation’s HEARTS Technical Package as an example. Its aim is to provide a public health approach to hypertension and cardiovascular disease (CVD) management in primary care. And it begins with lifestyle: diet, exercise, salt reduction, weight control, and quitting smoking. Those are foundations that can then be layered with standardised treatment protocols and medications where deemed necessary.

This structure is significant. Far from the image of doctors just wanting to prescribe pills, the most respected global protocols start with lifestyle and build up to medication when risk warrants it.

Bottom line: what’s the difference between eating garlic, taking garlic supplements, or taking medication?

While fresh, raw, or cooked garlic can be a healthy addition to a balanced diet, its active compounds, such as allicin, are unstable and vary widely depending on how the garlic is prepared, stored, or even chopped. That means it’s very difficult to know how much of the beneficial compounds you’re actually getting from food alone.

Garlic supplements are therefore designed to concentrate those compounds, but not all are created equal. Research shows that aged garlic extract currently appears to be a more reliable form for blood pressure support because it contains S-allylcysteine, a stable compound that allows for consistent dosing. Aged garlic extract has also been found to not increase bleeding risk when taken with blood-thinning medications (source).

Medications are standardised, tightly regulated, and backed by extensive clinical data showing they lower blood pressure predictably and reduce the risk of heart attack, stroke, and death. Garlic, especially in its aged extract form, can complement this approach. Which option is most appropriate will depend on individual risk and medical history, so decisions about supplements or medication should always be made in consultation with a doctor.

Let’s start with a bit of context: what is hypertension? And how can eating garlic affect blood pressure?

What is hypertension?

Hypertension means blood pressure that stays too high over time (typically confirmed in UK practice at ≥140/90 mmHg in clinic or ≥135/85 mmHg at home). It is a leading modifiable risk factor for heart disease and stroke (source, source).

Hypertension usually causes no symptoms, which is why it often goes undetected, but the good news is that it can be effectively controlled with lifestyle changes (including dietary changes) and medication when needed (source).

A recent study dispelled the commonly shared idea that cardiovascular events strike without warning. The researchers analysed health records from two large cohorts (over 9 million individuals in South Korea and nearly 7,000 in the U.S.). They found that 99% of those who experienced a stroke, heart failure, or coronary heart disease had at least one major risk factor (such as blood pressure, cholesterol, or glucose) at non-optimal levels. Notably, they found that high blood pressure was the most commonly present risk factor, found in more than 95% of South Korean patients and over 93% of U.S. patients.

This highlights the importance of prevention. In that sense, emphasising the benefits of garlic consumption to support healthy blood pressure can indeed be beneficial to the general public. However, this should not come at the expense of guidance from health professionals, or dismissal of effective medical treatments. Dietary and medical interventions should be seen as complementary tools rather than in competition when addressing such a prevalent global health issue.

What Eric Berg’s post gets right

To start with the good news: there are plenty of reasons to eat garlic. It provides vitamin C, vitamin B6, selenium, and fibre, alongside sulphur-containing compounds that play active roles in the body.

Garlic has long been studied for cardiovascular benefits. It is thought to help lower high blood pressure mainly because it contains natural sulfur compounds (especially allicin and S-allylcysteine) that help blood vessels relax, improve how they widen, and reduce inflammation and oxidative stress. These effects make it easier for blood to flow and can modestly lower blood pressure over time.

Clinical studies, particularly those using aged garlic extract or standardised garlic powders, show that garlic supplementation can reduce high blood pressure in people with hypertension and has potential for cardiovascular protection (source, source). In one randomised controlled trial, participants who took two capsules of aged garlic extract daily saw an average reduction in systolic blood pressure of 11.8±5.4 mm Hg compared with those taking a placebo (P=0.006). The “± 5.4 mmHg” shows how much this effect varied among participants, and the reported P = 0.006 indicates that this difference was statistically significant, meaning it was unlikely to have occurred by chance.

In practical terms, this means that taking aged garlic extract in this study led to a measurable and statistically reliable drop in systolic blood pressure. That change is large enough to be clinically meaningful: large-scale analyses show that lowering systolic blood pressure by 10 mmHg reduces the risk of coronary heart disease by about a quarter, and the risk of stroke by about one-third, with similar benefits across different patient groups (source).

However, the presence of beneficial compounds in a food doesn’t automatically mean that eating it will reproduce the same effects seen in controlled supplement trials. This distinction, between a nutrient’s potential in theory and its measurable impact in everyday diets, is an important component of nutrition science. Before drawing conclusions, researchers must ask key questions: how much of the active compound is absorbed from food? Is this an achievable amount for people to consume daily? How stable is it after cooking or digestion? How does it interact with other nutrients, and how consistent are its effects between individuals? The same reasoning applies to other foods rich in promising compounds, such as flavonoids in dark chocolate or resveratrol in red wine: both show cardiovascular benefits in studies, but that doesn’t mean eating chocolate or drinking wine daily will yield the same outcomes. These are the caveats scientists must address before moving from lab findings to everyday health guidance.

It is in this context that the above results from trials on garlic supplementation and hypertension should be interpreted. Firstly, studies consistently emphasise that garlic shows promise as a “complementary treatment option” for hypertension (source, source), rather than as a replacement. Secondly, the effects are most consistent in people who already have high blood pressure (source). Finally, the form of garlic (fresh cloves, powders, oils, aged extracts) matters, as does the dose. Many trials used capsules delivering controlled amounts of allicin or S-allylcysteine, which raw garlic cannot reliably provide. And results across studies vary, leading review authors to stress that more large, long-term research is needed before confident guidance can be offered.

Can we “just eat garlic” in the meantime? Absolutely, but leaving out the above information about how scientists move from observed properties to effective medical treatments can leave readers with a distorted understanding of the purpose, use, and context of such medications.

Be skeptical of one-sided arguments: Valid information considers multiple perspectives.

Eric Berg, D.C. recently remarked that pharmaceutical companies were “heavily researching garlic for its blood thinning properties,” asking his audience: “Instead of waiting for them to produce a drug that mimics its effects, why not just eat garlic?”

This fact-check digs deeper into the science behind garlic and hypertension, and looks closer at the logic behind this post: what are its implications, and are they backed by scientific evidence?

The facts: garlic can play a helpful role in supporting heart health, and a balanced diet is key to long-term prevention.

The framing: posts like this often present those findings to imply that drugs merely mimic food effects, suggesting a false choice between natural and medical care. In reality, evidence-based care can combine both: using diet to lower baseline risk and medication when needed to keep it under control.

When posts on social media suggest that eating certain foods like garlic makes drugs unnecessary, the problem lies not only in the facts themselves but in how those facts are presented, in a way that undermines evidence-based care. Communication matters. Language does more than transfer information; it shapes how people reason about food, health, and risk. This is why fact-checks must pay attention to tone and framing, as well as factual accuracy. Ultimately, distrust in medical interventions could lead some people to turn away from evidence-based treatments and have negative consequences for their health.

The fibre gap: why most of us fall short, and what Rhiannon Lambert’s new book adds

A quiet shortfall with big consequences

From media headlines to influencer advice, protein often takes the spotlight. Yet hiding in the shadows the nutrient that most of us under-consume is fibre. Public health bodies set adult targets around 25–38 grams per day, depending on sex and country. Actual intake? Consistently lower in the UK, the US, and across Europe, with only a small fraction of adults hitting the mark. (World Health Organization)

What fibre does for you

There are two types of fibre, soluble and insoluble. According to large public-health reviews and clinical guidance fibre does more than just support healthy digestion; it also helps manage cholesterol, blood glucose, and feeds the gut microbiome. Always aim for a mix of sources, since soluble and insoluble fibres work in complementary ways. (World Health Organization)

How big is the shortfall?

- UK: Recent analysis of the National Diet & Nutrition Survey (NDNS) indicates only about 4% of adults meet the 30 g/day recommendation. (Food Foundation)

- US: Average adult intake lands around 15–16 g/day, far below the 25 g/day (women) and 38 g/day (men) Adequate Intake levels. (Economic Research Service)

- Europe (overall): Most adults fall short of the 25 g/day benchmark; many national averages sit in the high teens to low twenties. (eufic.org)

These numbers align with the long-term pattern captured by national surveys. However, the WHO guidance encourages at least 25g/day of naturally occurring dietary fibre for adults. From this it is clear that there is a big shortfall.

(GOV.UK)

Why we’re missing fibre

It’s not one thing, it’s a pattern: refined carbohydrates displacing wholegrains, meals eaten away from home that tend to be lower in fibre, and a general underemphasis on legumes, nuts, seeds, and veg. US data show “at-home” foods have higher fibre density than many restaurant options, which nudges intake down when we rely on eating out. (Economic Research Service)

Closing the gap, one plate at a time

No hero foods required. Small, steady swaps add up:

- Choose wholegrain versions of breads, cereals, and pasta.

- Add one portion of pulses to a meal most days.

- Keep a “default” snack of fruit, nuts, or roasted chickpeas.

- Build “plants first” plates, then layer protein and healthy fats.

If you’re increasing fibre, go gradually and drink water to keep things comfortable. (Health)

Author spotlight: Rhiannon Lambert and The Fibre Formula

Rhiannon Lambert is a UK Registered Nutritionist, Sunday Times bestselling author, and founder of the Harley Street clinic Rhitrition. She hosts the Food for Thought podcast and co-hosts The Wellness Scoop with Ella Mills. Her previous titles include The Science of Nutrition and The Science of Plant-Based Nutrition and The Unprocessed Plate. (Rhitrition)

Her forthcoming book, The Fibre Formula: Eat Your Way to Better Health Through the Power of Fibre, positions fibre as the overlooked cornerstone of everyday health, with practical strategies and recipes to help readers meet daily needs. According to the publisher’s announcement, the UK release is slated for March 2026 and the US release for June 2026, with a central claim that around 96% of people are deficient in fibre—a framing consistent with NDNS findings that only a small minority meet targets.

“We’ve never had a protein deficiency crisis in the UK, yet protein dominates our supermarket shelves and social feeds. Meanwhile, fibre… barely gets a mention,” Lambert notes in the announcement, underscoring the book’s goal of practical, no-gimmick ways to hit fibre goals.

Quick reference: daily fibre targets

- WHO guidance: Adults should consume ≥25 g/day of naturally occurring dietary fibre. (World Health Organization)

- US Adequate Intake: ~25 g/day (women), 38 g/day (men); Daily Value on labels is 28 g. (Economic Research Service)

- UK recommendation: 30 g/day for adults, monitored via NDNS reporting. (Food Foundation)

Final thought

Fibre isn’t a trend, it’s infrastructure for health. The simplest path forward is to make high-fibre choices the default: wholegrains over refined, pulses most days, and plants in every meal. That steady approach, echoed by Lambert’s upcoming The Fibre Formula, is how most people can bridge the gap without fuss.

Does infant formula cause autism? Why the science says no, and why raw goat’s milk is not a safe alternative

What is autism?

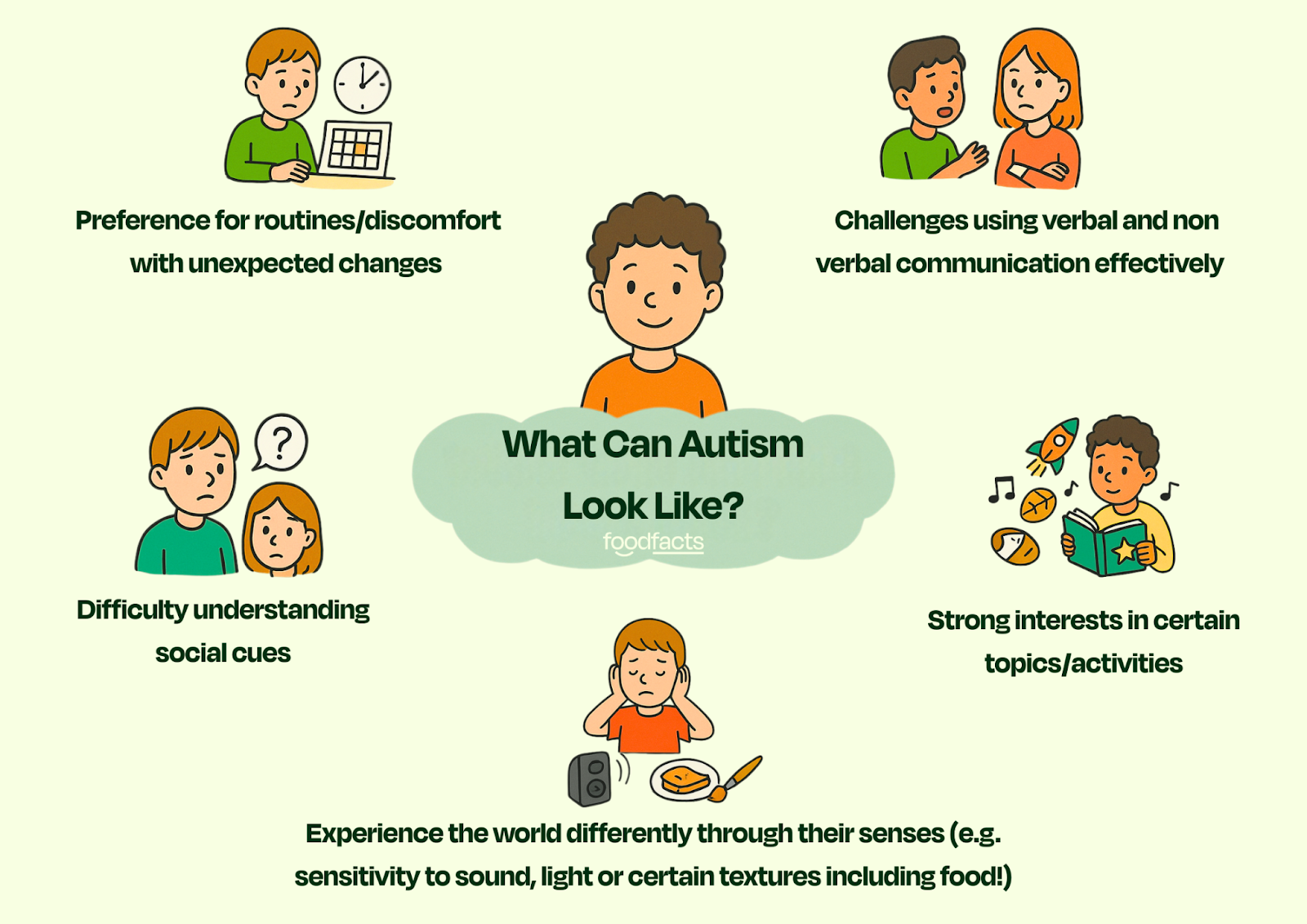

Autism or Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition, meaning it is related to the way the brain and nervous system grow and develop. Other neurodevelopmental conditions include ADHD and dyslexia.

Autism begins in early childhood and lasts throughout life. It often affects how a person experiences the world, communicates and relates to other people.

Autism is often referred to as a spectrum as it can vary largely from person to person. Different symptoms, abilities and support needs mean that some autistic people need daily support, while others can live independently.

Despite recent political debates about finding a 'cure', accompanied by negativity in the media, autism is not considered an illness, and is best understood as a difference, according to the National Autistic Society (source). Ongoing research into the causes of autism is not about ‘curing a disease,’ but about better understanding why autism develops, which may help prevent some cases and, just as importantly, improve support for autistic people and their families, especially those for whom autism is profoundly challenging.

What makes it so difficult to establish causation?

There is currently no biological test for autism. Instead it is diagnosed based on observed behaviour.

Autism is complex and highly individualised which makes it difficult to pinpoint a single clear cause. Even in research methods that give us some of the clearest insights, such as twin studies, there are still inconsistent conclusions about the causes of autism (source).

As with many complex conditions where research is still ongoing, a lack of clear answers leaves space for misinformation to spread. Over the years, a wide range of unsupported hypotheses have circulated — from outdated ideas such as “neglectful parenting” (now fully disproven) to more recent claims involving things like acetaminophen, blue light or infant formula.

But what does the evidence actually tell us about the causes of autism? Let's have a further look at the food-related claims and the science behind them.

Claim 1: “I thought the primary driver [of autism] would be vaccination, but it turns out that it's infant formula and blue light coming from screens.”

Fact-check: Although presented as though supported by newer and stronger evidence, this claim is misleading. The phrase 'primary driver' is inaccurate, and there is currently no credible scientific research concluding that infant formula is a cause of autism.

Current evidence shows that genetics play the biggest role in autism. More than 100 genes are already known to increase the likelihood of autism, and many more are expected to be identified in future research (source, source).

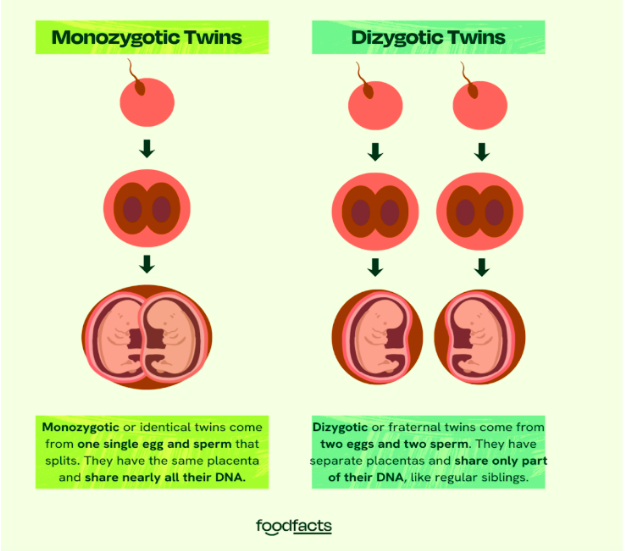

The strongest evidence of a genetic component comes from twin studies. These studies compare monozygotic (identical) twins and dizygotic (fraternal or non identical) twins.

If autism were mostly caused by environmental factors, then we’d expect identical twins and fraternal twins to have roughly the same chance of both being autistic. However, research shows that identical twins are much more likely to both have autism than fraternal twins. This shows there is a strong genetic component.

However, the fact that not all identical twins are both autistic shows that environmental factors also play a role. Most research shows that these environmental factors are mostly prenatal (aka take place before birth) (source). These include things like maternal infection during pregnancy, exposure to certain medications (such as valproic acid), and possibly maternal antibodies. Scientists also study epigenetics (i.e., the way experiences and environments can ‘switch genes on or off’ without changing the DNA itself) as another possible way these early influences might interact with genetics. These influences are less “primary drivers” but rather risk factors that, in combination with genetics, might contribute to autism.

Infant Formula

There is currently no strong scientific evidence that infant formula causes autism. In fact, one large scale study involving over 150,000 children found no significant association between soy-based infant formula and the risk of autism, as well as other neurodevelopmental outcomes such as epilepsy and ADHD (source).

Some studies have reported an association between breastfeeding and lower odds of autism. However, this does not mean that formula feeding causes autism. While associations can be helpful in research, they do not establish causation. This is because there are many confounding factors that can explain those findings. Lifestyle conditions such as socioeconomic status or maternal health may play a role. Reverse causation is another possibility, since early neurodevelopmental differences linked to autism might make breastfeeding more difficult in the first place. Beyond that, breastfeeding and formula feeding differ in ways that go beyond nutrition: breastfeeding involves skin-to-skin contact, hormonal responses, and the natural transfer of bacteria from mother to infant, while formula feeding involves different patterns of interaction. Researchers are exploring whether these differences could influence infant development through epigenetic effects, that is, changes in how genes are switched on or off by early experiences (source). Taken together, these factors mean that one study showing an association does not prove that bottle feeding causes autism.

For example, this study used a large, nationally representative cross-sectional sample (ages 2-5) and found no statistically significant association between breastfeeding and ASD after adjustment for demographic factors. This suggests that any effect, if present, is likely small or confounded by other factors. The authors note that discrepancies between studies may largely be due to differences in how researchers adjusted for confounding variables, and conclude that their findings are consistent with most previous studies having adjusted for confounding factors.

Bottom line

When this limited evidence is considered alongside the strong genetic research on autism, it is clear that infant formula is not a ‘primary driver’ of autism. When a study shows an association between infant feeding practices and the development of autism, more questions need to be asked before definite conclusions can be drawn: how do we know that the use of formula was to blame? What other factors could account for the observed association? These are questions that scientists carefully consider by looking at the overall balance of evidence on a given question before public health guidance might be updated. Misleading claims about ‘primary drivers’ of autism risk not only distorting the science, but also undermining trust in the scientific process itself.

Further consequences of this narrative are guilt among an already very vulnerable group, which could lead parents to turn away from evidence-based care, and to turn to alternatives that aren’t promoted by health professionals or that have been shown to be unsafe. This includes feeding infants raw goat’s milk.

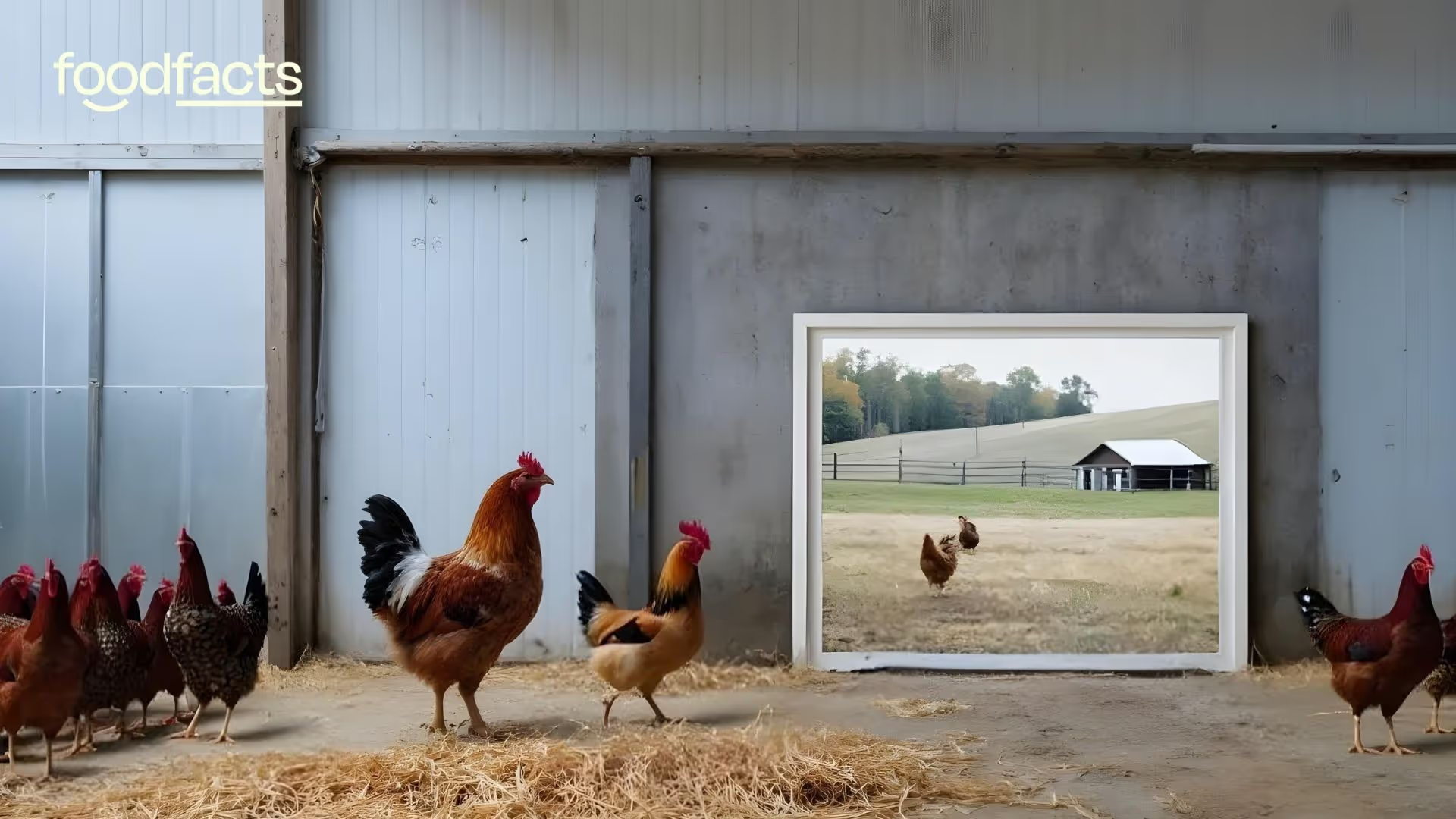

Claim 2: Non-pasteurised, non-homogenised goat’s milk might be offered when breastfeeding isn’t possible.

When asked what advice she would give mothers struggling to breastfeed, Barbara O’Neill starts by suggesting goat’s milk formula. While goat’s milk formula is a regulated and nutritionally adequate option, the discussion implied that raw goat’s milk could also be promoted if it came from a “healthy source” and was prepared with clean utensils.

Fact-check: Following this advice could lead to serious consequences. Infant formulas are carefully regulated to meet babies’ nutritional needs. On the other hand, unmodified goat’s milk is nutritionally inadequate, and raw milk carries serious infection risks (source, source).

Unbalanced nutrient profile

O’Neill claims goat’s milk is ideal for babies because goats are similar in size to human infants. This is misleading. The nutrient composition of milk is shaped by each species’ biology and the growth needs of its young (source), not by how big the animal is.

These differences in needs and milk composition mean that on their own, cow’s milk and goat’s milk aren’t suitable for babies. The protein levels are too high (putting stress on infant kidneys), and they don’t naturally contain the right balance of sugars, vitamins, and minerals that infants need. That’s why formulas made from cow or goat milk are specially processed: they’re diluted and fortified to make them safe and nutritionally complete for babies.

The composition of infant formulas attempts to best mimic that of human milk. For example, while the presence of seed oils in formula is often the target of criticism on social media platforms, and is also the subject of discussion in this podcast, it is important to remember that it is there to provide essential omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids that are critical for babies’ brain development. For a deeper dive into those issues, check out this related fact-check.

Risk of severe folate deficiency and anemia

Goat’s milk is naturally low in folic acid, and raw/unmodified forms lack essential vitamin fortification (source, source). Case reports show infants fed raw goat’s milk or homemade goat’s milk formula developed macrocytic anemia, a condition where red blood cells are abnormally large but don’t function properly. Other severe complications, including stroke, kidney damage, and life-threatening allergic reactions, have also been reported.

Dangerous infections

The risks associated with the consumption of raw goat’s milk are not merely theoretical: the history of milk-borne disease shows us what can go wrong (source). Raw goat’s milk can carry pathogens such as Q fever (Coxiella burnetii), listeria, toxoplasmosis or brucellosis. These infections are particularly dangerous for infants with immature immune systems. Ironically, while O’Neill and Gary Brecka discuss the importance of gut health and immunity, infections caused by drinking contaminated raw milk could seriously disrupt the gut microbiome and weaken the immune system.

While some studies have observed potential protective effects of raw milk against conditions like respiratory infections, even then the authors stress that such benefits would only be meaningful if the infection risks were eliminated, which is why unprocessed milk continues to be discouraged, particularly in infants.

Bottom line

The scientific literature on reports of complications from infants’ consumption of raw goat’s milk makes it clear that following this advice could have dangerous consequences, and that there remains a lack of awareness regarding the severity of such complications.

O’Neill acknowledged that promoting raw goat’s milk was one of the reasons she was banned from practicing in Australia, following a Health Care Complaints Commission ruling that her advice had the potential to harm vulnerable populations.

Distrust in infant formulas fuelled by such misinformation has also led people to turn to making their own homemade formulas (source), with reports of infants presenting with severe health complications (source).

Beyond the direct dangers of raw milk, these claims reflect a broader narrative that fuels distrust in safe, regulated medical and nutritional practices. When it comes to autism research, oversimplifying the science doesn’t just spread misinformation, it also weakens scientific literacy. Instead of encouraging people to understand how evidence is built and weighed, it stirs up guilt, fear, and confusion. And those emotions can make it harder for parents and the public to trust real science when they need it most.

We have contacted The Ultimate Human Team, who have clarified that the podcast is aimed at encouraging open discussion, and that the suggestions or opinions expressed by guests do not necessarily reflect the brand’s views.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Be skeptical of messaging that oversimplifies complex conditions or health issues. Credible health advice comes from large-scale research and expert consensus, not anecdotes alone.

On a recent episode of The Ultimate Human Podcast published on September 23rd, 2025, Gary Brecka discussed a new MAHA report that would soon explore ‘the root causes of autism.’ While the latest U.S.’ government’s announcement focused on acetaminophen (Tylenol), Brecka and guest Barbara O’Neill shifted the conversation toward infant formula and then discussed the suitability of raw goat’s milk for infants who are not breastfed. The podcast team has since clarified to us that given the nature of podcasts, the views expressed in an episode might not necessarily reflect the views of the team or brand itself.

This article checks those claims against the available scientific evidence, and summarises its implications for parents, infants and for public health.

There is no credible evidence of a causal link between infant formula and the development of autism. Autism is a complex condition that is strongly influenced by genetics, with environmental factors playing a secondary role, mainly before birth. For infants who are not breastfed, commercial formulas, whether cow-, soy- or goat-based, are strictly regulated and nutritionally adequate. Raw goat’s milk, however, lacks key nutrients and can transmit dangerous infections, making it unsafe for infants.

Misinformation about infant feeding can have serious consequences. Suggesting that formula is a “driver” of autism risks creating guilt and fear among parents who cannot or choose not to breastfeed. Even more concerning, suggesting raw goat’s milk as a potentially safe substitute could lead to severe nutrient deficiencies and infections in infants. At a time when trust in health guidance is already under pressure, claims like these risk pushing families toward unsafe alternatives.

How analogies shape nutrition debates: power and limitations to be aware of

Social media thrives on catchy comparisons. Jessie Inchauspé, better known as the Glucose Goddess, says she often hears doctors say that “If you don’t have diabetes, you don’t need to worry about glucose.” She responds with an analogy: “That’s like saying if you don’t have cavities, don’t bother brushing your teeth.” Meanwhile, Eric Berg, D.C. warns his audience that their health issues might well be caused by the fact that they could be consuming 25 to 30% of their daily calories from “engine lubricant,” an analogy he uses to refer to canola oil.

These analogies spread far and fast because they’re easy to understand, emotionally charged, and memorable. But what makes them powerful also makes them risky. To unpack why, we need to understand what an analogy actually does at the cognitive level. In other words, what is the purpose and what are the effects of comparing two otherwise unlike things (“X is like Y”) in the context of nutrition information?

The power, and the limits, of analogy

An analogy highlights what two things share in common. Analogies can be a great tool to expand reasoning, because by doing so, they can get you to make new connections that you might not otherwise have made, to think of an issue in a new perspective. But they can also mislead, so it’s very important to know what to look out for when you hear an analogy in the context of nutrition information.

Analogies and metaphors are a prominent object of study within the field of linguistics, precisely because of their impact on reasoning. They do two things: highlight and hide. In highlighting one similarity, an analogy may also hide other differences. That’s not inherently bad. To think productively, we often need to filter out what’s irrelevant. But when the hidden differences matter, analogies can mislead.

Let’s look at our two selected examples more closely:

Brushing your teeth ≠ managing your glucose

At first glance, the Glucose Goddess’s analogy feels intuitive and reasonable: brushing teeth is a preventive routine, and surely glucose management should be too, before conditions such as Type 2 Diabetes have time to develop. But the problems appear as soon as you examine what the analogy hides.

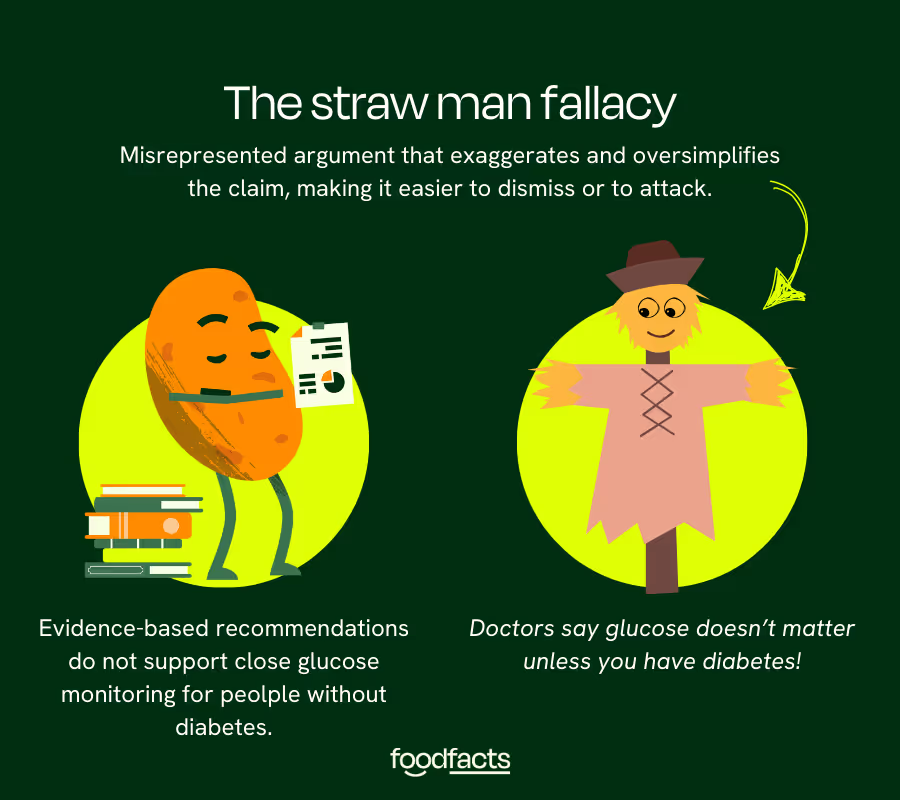

1. It misrepresents medical advice. Doctors who tell people without diabetes not to worry about glucose spikes are generally not saying that glucose does not matter, as the analogy implies.

Context is important, and it is exactly what is missing here. Two essential bits of context are missing here. Firstly, when doctors say that people without diabetes do not need to closely monitor their glucose levels, they say so in the context of a well-balanced diet. Secondly, this advice most likely refers to the recent trend of using continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) among people without diabetes. CGMs are life-saving devices, designed for those with diabetes. They work by measuring glucose in the extracellular fluid (rather than directly in the blood), so they are great for measuring changes to glucose in those with diabetes, where the highs and lows are more dramatic. But they may be less accurate in those with more stable blood sugar levels (source). The point of the medical advice is therefore not to dismiss glucose management, but to caution against unnecessary monitoring where it lacks evidence of benefit.

This distinction matters, because the analogy sets up a straw man. The straw man fallacy works as a distraction: while listeners are drawn to what feels like a reasonable conclusion (glucose management matters to prevent diabetes), attention is pulled away from the real premise. By subtly rephrasing doctors’ position, the analogy makes it easier to refute, presenting an appealing but misleading critique of medical advice.

This might seem like a small tweak, a mere matter of semantics. But actually, the issue isn’t so much with what is said (you should monitor your glucose!), but with how it’s communicated, in a way that undermines evidence-based dietary guidelines and the health professionals who recommend them. Because what is shared here is not merely information about the importance of glucose management, but a critique of doctors’ understanding of such issues, and of their careless advice (who would advise anyone that brushing teeth isn’t important?). This becomes especially problematic over time, as we get more and more exposed to this type of messaging.

2. It ignores normal physiology. For people without insulin resistance, glucose rises after meals and then returns to baseline. This is a normal process, not something that needs to be tracked continuously. Jessie Inchauspé has faced criticism from health professionals who argue that her approach pathologises a normal phenomenon. But this critique does not come from a careless disregard for prevention. It comes from an understanding of physiology, and from concern about the unintended consequences of encouraging people to treat everyday glucose fluctuations as harmful. Focusing on these normal responses risks fostering almost obsessive attitudes towards food, in ways that are not supported by evidence.

Encouraging everyone to track every spike risks narrowing focus to numbers while missing the broader picture of balanced eating. Eventually, this can lead to flawed choices. For example, you might adopt extreme low-carb eating to blunt every spike but end up consuming too much saturated fat, raising cardiovascular risk. While tracking glucose levels offers a tangible object of measure, there is no daily device that can provide you a number indicating how close you might be to a heart attack.

3. It hides differences in causal processes. Ultimately, the mainstream dietary advice to eat plenty of fibre, vegetables, wholegrains, and to limit ultra-processed foods already achieves the same glucose management benefits Jessie promotes, without feeding an obsessive attitude towards glucose monitoring in otherwise healthy people, which comes from construing glucose ‘spikes’, a normal scientific term, as something inherently harmful, in the same way dental cavities might be.

Cavities develop directly from bacteria producing acids that erode enamel, which happens to everyone if teeth are not cleaned. Glucose spikes after eating are not inherently harmful in people with healthy insulin sensitivity. Presenting them as equivalent processes distorts the science.

More importantly, by thinking of them as equivalent processes we can start developing negative attitudes towards food, where every bite is seen as potentially harmful. Again, this is something that happens over time, as we get more and more exposed to similar messaging. In fact, this is a common thread on social media, which often profiles this type of very direct causal relationships (“Make this simple change and see your life improve!” or on the other hand, “Eat this and see your health deteriorate!”). When we start seeing food as either danger or medicine, with no room for a middle ground, we risk fostering rigid and unhealthy eating attitudes that can lead to anxiety, guilt, and even disordered eating. Research shows that extreme perceptions of food, especially those driven by emotional associations or rigid health beliefs, can contribute to food preoccupation and bulimic tendencies, which in turn negatively affect dieting attitudes (Dicu et al., 2024). Although some “Food as Medicine” programs have shown success in improving dietary confidence and food literacy (Nara et al., 2019), there's a growing concern that oversimplified health messaging, particularly on social media, can distort this concept into a source of fear and control rather than empowerment. If taken to extremes, even well-meaning ideas about food can turn into triggers for orthorexia or other eating pathologies (Erol & Özer, 2019).

4. It downplays the difference in stakes. Cavities can be repaired. Diabetes is a systemic condition that involves insulin resistance and loss of beta-cell function. It is serious and not corrected with a single intervention. Crucially, it is not an issue that doctors take ‘lightly’.

This is why the analogy moves from catchy to misleading. It both misrepresents expert advice and creates a false equivalence between two very different biological processes.

Bottom line

From a cognitive perspective, the Glucose Goddess’ analogy works by highlighting not just the importance of prevention, but the idea of inadequate prevention. It suggests that doctors downplay glucose management in the same way it would be inadequate to say “only brush your teeth once you have cavities.” This resonates because it appeals to common sense about acting early to avoid problems, and to feelings of not being taken seriously by an overwhelmed health system.

But in doing so, the analogy takes the focus away from the fact that medical advice already promotes prevention through balanced diets and healthy eating patterns. What it distracts from is the real issue: most people do not follow dietary guidelines. And that is not a matter of laziness or ignorance. It reflects a food environment and lifestyle that make healthy choices difficult — cheap, convenient options are often the least nutritious, while time, cost, and access create major barriers.

The result is a narrative that erodes trust in experts by framing them as dismissive, while shifting attention away from the broader systemic drivers that actually explain why healthy dietary guidelines are so hard to follow in practice.

Engine lubricant ≠ canola oil

Dr. Berg’s analogy is more blunt: canola oil is cast as “engine lubricant,” invoking disgust and what feels like direct danger. Again, what’s highlighted is memorable: industrial processes, chemicals, machines. This seems to be completely at odds with healthy eating, with the focus on whole foods that are nourishing and support well-being. But while what’s highlighted is memorable, what’s hidden is critical.

The reality is that industrial rapeseed oil and culinary canola oil are genetically different. Canola is bred specifically for food use, with very low erucic acid levels that regulators monitor closely (source). Its fatty acid profile — mostly unsaturated, with some omega-3 — is considered heart-healthier than animal fats when used in moderation. In fact, it has a very similar make up to olive oil, which is often acknowledged as healthful by the same people who demonise seed oils.

But the analogy does more than spread some inaccuracies about the genetic make up of canola oil. It is grounded in the appeal to nature fallacy, and it ignores that processing isn’t inherently harmful. This distrust of anything synthetic isn’t harmless, as it could impede food innovations that might support a move towards a more sustainable food system, for example.

The analogy also overlooks the fact that many foods have applications outside of food, but the regulations tend to be very different depending on their intended use. Take corn, for example. The same crop can be milled into flour for tortillas or bread, popped into popcorn, or fermented into ethanol fuel for cars. These products follow entirely separate processes and safety standards. No one would suggest avoiding corn on the cob because corn can also be used to power an engine.

Most importantly, the analogy distracts from the role of ultra-processed foods (UPFs). Much of the canola oil we consume comes via processed snacks, baked goods, and fast food. The health issue isn’t that canola oil is “engine lubricant.” It’s that too many of our calories come from foods that are calorie-dense, fibre-poor, and loaded with sugar and salt. The analogy distracts from the real problem: dietary patterns, not one single ingredient.

Why this matters for media literacy

Analogies can clarify ideas, but they can also derail reasoning. They thrive on social media because they fit neatly into short posts, carry emotional punch, and make science sound simple. But that simplicity comes at a cost.

When you encounter an analogy online, pause and ask:

- What does it highlight?

- What does it take the focus away from? Where does the analogy stop being useful?

- Does the comparison really match the underlying processes, or is it a false equivalence?

- Does it misrepresent what experts actually say, setting up a straw man?

- Does it ignore how food is regulated, or the difference between food and non-food uses?

- Does it reduce the problem to a single ingredient, when the real issue is overall dietary patterns?

- Does it shift responsibility onto individuals while overlooking the food environment that shapes choices?

By recognising these patterns, we can appreciate analogies without losing sight of the bigger picture, of the changes that will actually make a difference to our health.

The bigger picture

Nutrition advice, stripped of drama, remains consistent: eat a variety of plant-based foods, get sufficient fibre, limit ultra-processed foods, keep added sugars and salt in check. Within that framework, occasional glucose “spikes” are normal, and cooking with canola oil is not the same as drinking from a car engine.

Analogies make nutrition sound like a battle against hidden enemies. Media literacy reminds us that the real challenge is balance.

Sustainable weight management backed by science: 7 long-term strategies that work

Weight management remains one of the most frequently searched health topics online. Unfortunately, this interest has fuelled a market saturated with fad diets, miracle solutions and conflicting advice. While quick fixes often capture attention, the evidence consistently shows that sustainable weight management relies on gradual, consistent changes. These approaches not only support long-term weight stability but also protect both physical and mental health. So, what strategies are supported by science?

1. Focus on dietary patterns, not single foods

No individual food determines success or failure. The strongest evidence supports dietary patterns built around minimally processed, nutrient-dense foods1. For example, the Mediterranean dietary pattern is associated with lower cardiovascular risk, improved metabolic health and more sustainable weight management2.

Core elements include2:

- A high intake of vegetables, legumes, wholegrains, fruits and nuts;

- Olive oil as the main fat source;

- Moderate amounts of fish, with limited red and processed meats.

2. Balance energy intake with energy needs

Energy balance underpins weight change. Extreme calorie restriction often backfires, leading to rebound weight gain and reduced adherence3. Instead, sustainable approaches emphasise:

- Building awareness of energy density as high-energy dense foods can substantially increase overall intake compared with lower-density options, even without larger portion sizes4.

- Developing awareness of food labels, particularly for added sugars, artificial sweeteners, saturated fats and emulsifiers as these can influence the healthiness of products purchased5.

- Building habits that encourage natural moderation (e.g. mindful eating6, food diaries7)

These strategies improve awareness without encouraging obsessive tracking.

3. Prioritise protein, fibre and plant diversity

Protein-rich foods, such as, legumes, dairy, fish, tofu and lean meats promote satiety and help preserve lean muscle mass, a key factor for maintaining metabolic health8. Fibre-rich foods, including vegetables, fruits and wholegrains further support weight management by slowing digestion, stabilising blood glucose9 and enhancing fullness9.

Importantly, it’s not just the amount of fibre that matters but also plant diversity. Consuming around 30+ different plant types per week, spanning fruits, vegetables, legumes, wholegrains, nuts, seeds, herbs and spices (yes, even coffee and dark chocolate contribute) has been associated with greater gut microbiome diversity10, which in turn correlates with improved metabolic outcomes and weight regulation11. Emerging evidence also suggests that probiotics, which increase populations of beneficial gut bacteria, may be effective in improving BMI and reducing body weight12.

Rather than focusing on restriction, an “add-in” approach is more sustainable. Examples include:

- Adding berries to oats;

- Swapping white rice for quinoa or brown rice;

- Mixing lentils into soups or curries;

- Sprinkling nuts or seeds onto salads;

- Using a variety of herbs and spices to enhance flavour and plant variety.

This method makes healthy eating feel less like a rulebook and more like nourishment.

4. Physical activity is essential

Exercise alone does not guarantee weight loss, but it is critical for weight maintenance and long-term health. Research highlights two pillars:

- Resistance training: supports muscle preservation, helps to increase metabolic rate and reduce weight13.

- Aerobic activity: promotes cardiovascular health and increases energy expenditure14.

Together, they form the foundation for sustainable management and overall wellbeing.

5. Sleep and stress are as important as diet

Sleep and stress directly influence appetite-regulating hormones. Poor sleep can reduce leptin (the hormone that signals when we’re full) and increases ghrelin (our hunger hormone)15. Insufficient sleep has been linked to heightened cravings for energy-dense, high-calorie foods16. Longitudinal research further shows that individuals who regularly sleep fewer than 6–7 hours per night face a significantly greater risk of weight gain over time17.

Chronic stress compounds this by elevating cortisol, which encourages fat storage and alters eating behaviours18. Prioritising sleep hygiene and stress-reduction strategies (e.g., mindfulness, relaxation techniques, social connection) is not optional, it is evidence-based care.

6. Behavioural and psychological strategies

Lasting change depends not only on what you eat but how you sustain new behaviours. Techniques with strong evidence include19:

- Goal setting and self-monitoring;

- Problem-solving and relapse prevention;

- Professional support and accountability;

- Successful therapeutic relationship to reshape thinking around food and body weight.

7. Avoid extremes and ditch the scales

Restrictive diets that eliminate entire food groups or drastically reduce calories may cause rapid short-term weight loss, but they are rarely sustainable3. Such approaches often result in nutrient deficiencies20 and rebound weight gain3.

When tracking progress, relying solely on scale weight can be misleading. The scale does not distinguish between fat mass, muscle mass or water retention, all of which fluctuate for different reasons. For example, gaining lean muscle while losing body fat may result in little change, or even an increase on the scale despite meaningful improvements in body composition and metabolic health. Research supports the use of multiple measures, such as progress photos, waist circumference, clothing fit, strength levels and subjective markers like energy and wellbeing, to provide a more accurate and holistic view of progress.

In Summary

Sustainable weight management is not about chasing the newest trend but about consistently applying proven fundamentals:

- Emphasise minimally processed, plant-rich dietary patterns;

- Balance energy intake with personalised needs;

- Include protein and fibre consistently;

- Aim for 30+ plant types a week to optimise your microbiome;

- Combine strength and aerobic training;

- Protect sleep and manage stress;

- Use behavioural strategies to reinforce lasting change;

- Don’t rely on scale weight as a marker of progress.

In practice, small, consistent actions accumulate into meaningful results. Weight management should not feel like punishment or perfectionism, it should provide a foundation for lifelong health.

Can we reverse Type 2 Diabetes with an animal-based diet?

To understand claims about dietary changes and type 2 diabetes, it helps to start with how the condition affects the body. In type 2 diabetes, the body’s cells don’t respond properly to insulin, the hormone that helps lower blood sugar. This means that no matter how much insulin the pancreas produces, diabetic individuals end up with all that sugar in their blood. Because of this, lifestyle strategies such as dietary changes can play an important role in managing the condition, though these are best pursued with the guidance of qualified health professionals.

Claim 1: “The healthiest way to do this is to: Cut out all ultra-processed foods.”

Fact-check: Cutting out soda, chips, candy, and greasy fast foods is universally recommended! However, not all foods classified as “ultra-processed” are harmful. The NOVA classification defines ultra-processed foods as those containing industrial ingredients like high-fructose corn syrup, hydrogenated oils, and flavour agents that are not found in our kitchens. But it also lumps in foods that can be healthy and convenient — like canned beans, fortified plant milks, or whole-grain breads with preservatives — simply if they have one of these ingredients.

A 2023 synthesis of three large cohorts found that ultra-processed food intake overall was linked to higher diabetes risk — but when broken down, refined grains, sugary drinks, and animal products increased risk, while whole-grain breads and fruit products reduced it. So avoiding sodas, sweets, and greasy fast food is clearly beneficial, but labelling all ultra-processed foods as harmful oversimplifies the evidence and may discourage people from choosing affordable, nutritious options that support diabetes management.

Claim 2: “Cut out all high-carbohydrate foods: grains, pasta, bread, cereal, fruit, honey, potato.”

Fact-check: While it is true that managing carbohydrate intake is central to diabetes care, this does not mean eliminating carbohydrates altogether but rather choosing high quality carbs.

The American Diabetes Association, for example, recommends that carbohydrates make up roughly a quarter of the plate, with an emphasis on whole grains, beans, vegetables, and fruits. That is because these foods provide fibre, vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals that not only support general health but also help regulate blood sugar through various mechanisms in the body. For example, whole grains like brown rice, quinoa, whole wheat bread versus refined grains like instant cereals, while rice and bread, crackers, chips, etc.

Extensive research backs this up. Meta-analyses show that people who eat more whole grains, fruits (excluding fruit juice), and beans/lentils (source, source) have lower insulin resistance, better lipid and glycemic control, lower body weight, and reduced risk for developing type II diabetes. So saying that all high-carbohydrate foods should be avoided oversimplies the science and may deprive people of foods that can actually help with blood sugar control.

Claim 3: “Replace these carbohydrates with animal fats: tallow, butter, ghee, lard. Centre all your meals around fatty meat, seafood, eggs.”

Fact check: This advice directly contradicts decades of scientific evidence and the recommendations of major health organisations. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease are often called “sister diseases” because they share common risk factors: obesity, hypertension, inflammation, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance. Any effective dietary intervention for diabetes must also reduce cardiovascular risk, not increase it.

High intake of animal protein has repeatedly been linked to increased risk of type 2 diabetes. For example, in three large U.S. cohort studies, raising red meat consumption by just ½ serving per day increased diabetes risk by nearly 50%. In contrast, replacing one daily serving of red meat with legumes or nuts lowered diabetes risk by 30%. Vegetarians consistently show a lower risk of type 2 diabetes than omnivores—evidence that contradicts the idea that animal products are essential for diabetes reversal.

While the claim is that type 2 diabetes can be reversed by stabilising blood sugar, lowering insulin, and shrinking fat cells, clinical trials show that plant-based diets can accomplish all three. Following a low-fat plant-based diet improved weight and blood sugar, reduced diabetes medications, improved beta-cell function, insulin sensitivity, and significantly reduced fat in liver and muscle cells—key drivers of insulin resistance.

These findings align with recommendations from the World Health Organization, American Diabetes Association, and the British Diabetic Association, which recommend limiting saturated fats and choosing lean proteins to prevent lipid abnormalities (high triglycerides, elevated LDL-C, and low HDL-C) that contribute to atherosclerosis. Tallow, butter, ghee, lard, and fatty meats are high in saturated fats, which experts advise limiting for better long-term health. A Nature Medicine study found that diets rich in plant-based unsaturated fats were associated with lower rates of both type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, compared with diets high in saturated animal fats.

Final take-away

These claims misrepresent nutritional science by ignoring evidence linking animal protein to type 2 diabetes, oversimplifying advice by cutting out entire food groups, and downplaying decades of research and global health guidelines. While small amounts of lean animal products can fit into balanced diets, the strongest evidence supports plant-based patterns, which consistently improve blood sugar control and cardiovascular outcomes. This type of narrative can also leave people feeling uncertain about who to trust, pulling them away from healthcare professionals and making it harder to feel confident in safe, evidence-based options.

We have contacted Lucy Fabbri and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Be cautious of “all-or-nothing” claims—for example, demonising entire food groups like carbohydrates. Nutrition is rarely that simple.

In a recent social media collaboration, multiple advocates for the carnivore diet, including @thatcarnivorenurse, Shawn Baker, and doctors Robert Kiltz and Anthony Chaffee, made the claim that eating an animal-based diet could ‘reverse type II diabetes’.

An excerpt:

“To reverse it [type II diabetes], you must change your lifestyle. Taking medications will not address this. Here is what you must do: stabilise blood sugar levels, lower insulin, shrink your fat cells, grow your muscles. The healthiest way to do this is to: Cut out all ultra-processed foods. Cut out all high-carbohydrate foods: grains, pasta, bread, cereal, fruit, honey, potato. Replace these carbohydrates with animal fats: tallow, butter, ghee, lard. Centre all your meals around fatty meat, seafood, eggs.” (Lucy, aka @thatcarnivorenurse on Instagram, July 1, 2025)

This fact-check evaluates the accuracy of those claims against current scientific evidence.

The best evidence shows that diets high in animal fats do not reverse type 2 diabetes — and may actually increase risk. Plant-forward, high-fibre diets remain the most effective for prevention and management.

Type 2 diabetes is estimated to affect over 460 million individuals worldwide. People living with the condition are often faced with an overwhelming amount of advice online, and it can be hard to know what’s reliable. It's true that type 2 diabetes can be "reversed" - blood sugar levels returning to normal without medication. This usually requires lifestyle changes including dietary modifications. However, cutting out whole food groups or eating mostly animal products is not supported by science. Such advice carries potential risks, including nutrient deficiencies and other health complications.

Latest fact-checks, guides & opinion pieces

.svg)