Influencer suggests Easter candy treats are dangerous. Here's what you need to know

Claim 1: Lindt Easter chocolate bunnies contain “soy lecithin that is linked to metabolic issues.”

The post implies that soy lecithin – an additive in chocolate – can lead to metabolic issues. Metabolic issues refer to problems with how your body turns food into energy. These can include high blood sugar, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and extra belly fat—all of which can increase your risk of serious health conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and stroke (source).

Fact-Check: Soy lecithin is a common food emulsifier derived from soybeans. It helps blend ingredients (for example, keeping chocolate creamy and smooth). Concerns around potential metabolic issues stem from studies on mice, in the context of high-fat diets (source). However, soy lecithin is present in minimal amounts in chocolate, and there is currently no direct evidence linking it to metabolic disorders at these levels.

The general safety of soy lecithin was recently re-evaluated by EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) which concluded that there are no safety concerns with the use of lecithins as a food additive, for the general population from more than 1 year of age (source).

Context Matters: Excessive intake of sugary foods overall could contribute to metabolic issues over time, but soy lecithin itself is not the primary concern.

Claim 2: Nerds gummy clusters contain “Red 40 that is linked to cancer and hyperactivity.”

Fact-Check: Red 40 (Allura Red AC) is one of the most commonly used synthetic food dyes and has been investigated for links to hyperactivity in children. The evidence points to potential behavioral effects, particularly in children with ADHD or food sensitivities (source). Effects include increased hyperactivity, restlessness, and reduced attention span. However, it is worth noting that not all children are affected and studies consistently highlight individual variation.

There is no conclusive evidence that Red 40 causes cancer in humans. This review found no new evidence to change the safety recommendations for Allura Red AC, but suggests monitoring high intake in young children (in the context of repeated, excessive intake as opposed to single events like Easter celebrations). No regulatory agencies currently classify it as a carcinogen.

Context Matters: It is important to note that the evidence does not support that food dyes like Red 40, in the quantities present in candy products, cause disorders such as ADHD, which can have many causes (genetics, environment, etc.) (source).

Claim 3: M&Ms contain “Blue 1 Lake linked to chromosomal damage and skin rashes.”

Fact-Check: Blue 1 Lake (Brilliant Blue) has been associated with rare allergic reactions such as hives or flushing in sensitive individuals. Regulator agencies have set Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) levels that include large safety margins for food dyes. For Blue 1 Lake, it is around 6–12 mg/kg/day (EFSA and FDA, respectively). For context, a whole bag of colorful candy might contain 30 mg of mixed dyes, well below these limits for a child on a single day.

The post’s mention of “chromosomal damage” likely refers to some lab experiments: high concentrations of Blue 1 in cell cultures or isolated systems have caused chromosomal aberrations (DNA changes) in those in vitro tests

(source). But in humans, such effects haven’t been observed at dietary levels.

Artificial dyes, and when they may cause health issues, boil down to dose and individual sensitivity. Regulators deem small amounts in foods (such as the occasional Easter egg) safe.

Claim 4: Sour Patch Kids’ jelly beans contain “corn syrup which increases risk of diabetes and fatty liver disease.”

Fact-Check: Corn Syrup is primarily composed of glucose, and is commonly used in baking and candy-making to prevent crystallization and add moisture. Nerds and jelly beans, for example, contain corn syrup or sugar as main ingredients (not surprising – they’re candy!). High-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) has been associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance in observational studies (source). However, corn syrup is different from HFCS, as it is mostly glucose, not fructose. The two are regularly conflated on social media.

Health experts agree that excess sugar consumption over time can contribute to weight gain, which increases the risk of several types of chronic disease, such as type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, or heart disease. However, it’s not about one specific source like corn syrup being uniquely poisonous – it’s about quantity and frequency.

Context Matters: The key issue here lies in chronic overconsumption rather than occasional indulgence. Children in Western countries eat a lot of added sugars in general, and that chronic overconsumption is linked to metabolic diseases. Large epidemiological studies show diets heavy in sugary drinks and sweets are associated with higher incidence of type 2 diabetes and obesity (source). Importantly, sugar itself isn’t a direct toxin that immediately causes disease – rather, consistently eating more calories (from sugar or other sources) than you burn leads to weight and metabolic issues.

Claim 5: “Your kid’s health and mood will change! Instantly.”

Fact-Check: While some parents report anecdotal behavioural changes after removing certain additives or high-sugar foods from their child’s diet, scientific evidence does not support instant improvements in mood or behaviour from single dietary swaps. For example, a recent systematic review found that while some dietary interventions might have small effects on ADHD symptoms in children, the evidence is not strong enough to recommend dietary changes as a standard treatment for ADHD - and the effects reported were not instantaneous (source).

Context Matters: Behavioural changes are complex and influenced by multiple factors beyond diet alone. Holidays like Easter often involve temporary deviations from regular eating patterns. Long-term dietary habits have a greater impact on health and behaviour than occasional indulgences (source).

Final Thoughts

We often say that ‘context matters’. It might be more fitting to say the lack of context matters even more, because it is what ultimately leads to poorly-informed decisions. Handling lots of sugary treats over the holidays can be challenging, but the ‘answer’ does not necessarily lie with a complete ban; on the other hand, just because a product is considered safe does not mean we should consume it every day with no moderation. It’s about making a distinction between habitual and occasional intake; between overall diet quality and treats.

This type of language, promoting instant changes following simple dietary swaps, is typical of social media content, driving engagement and emotional responses. But it does little to enhance nutritional understanding, and it distracts from real, pressing issues which are impacting public health. The fact that most people do not consume enough fibre or follow dietary guidelines is what needs to be addressed - and demonising food dyes won’t solve that problem.

Concerns about the heavy marketing of ultra-processed, nutrient-poor products to young children, combined with the lack of easy access to fresh products like fruits and vegetables are legitimate, and crucially need to be addressed to improve public health. However, social media trends promoting ‘toxic food thinking’ that distort scientific evidence distract from the real issues within our food system and can do more harm than good, particularly in the long run.

We have contacted Jen Smiley and are awaiting a response.

Trusted Experts Worth Following

For balanced, expert perspectives on issues such as food dyes and their impact on individual and public health, we recommend you to follow experts’ accounts, such as:

Dr Andrea Love’s Instagram account and newsletter, Immunologic;

Dr Jessica Knurick’s Instagram account and substack newsletter;

“Foodsciencebabe” on Instagram

Also check out this guide to better understand how to interpret results from animal studies in the context of nutrition guidelines.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

The 5 separate claims contained in this post all lack context, in a way that could contribute to a distorted view of nutrition and generate unnecessary fear. Let’s address the overall missing context before breaking down each claim and its implications for overall health.

The missing context: Dose, frequency, and overall diet

Crucially, the social media post fails to ask “in what context do these ingredients cause harm?” Each ingredient it demonises can sound scary without context. But doses make the poison. Regulators like the FDA and EFSA set strict limits and review safety data to ensure that, when these additives are used in normal amounts, they pose no significant risk to human health. There’s a world of difference between laboratory conditions or chronic heavy consumption and a child eating a few candies on Easter weekend.

Overall Nutrition: It’s true that many foods containing artificial dyes or lots of corn syrup are nutrient-poor ultra-processed foods. So, if a child is regularly eating candies, sodas, and neon-colored snacks at the expense of balanced meals, that’s more likely to cause health problems – not because of one molecule like Blue 1, but because the child is missing out on healthier foods (source).

For example, this review looked at 39 meta-analyses on the associations between consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) and health outcomes. The studies analysed consistently showed associations between a higher consumption of UPFs and an increased risk of various chronic diseases. The researchers concluded that emphasising dietary patterns with a low consumption of UPFs could lead to public health benefits. Further, recent research found that higher consumption of ultra-processed snacks may negatively affect metabolic health markers (source). This supports the idea that improving a child’s daily diet (more fruits, veggies, whole grains, etc.) can positively impact overall health and behaviour (source), but it does not suggest that occasional treats are inherently dangerous and need to be banned. In other words, it’s the pattern of eating that mostly matters. Occasional treats can fit into a healthy lifestyle.

While social media may tempt parents with ‘quick fixes’ for their children's health and behaviour, unfortunately it’s not that simple.

Yes, excessive or regular intake of additives and sugars can lead to poor health outcomes, but the ingredients in question are generally safe when consumed in standard portions. In fact, vilifying and restricting these may actually be more damaging to a child's relationship with food long-term.

Speculative claims based on anecdotal observations undermine evidence-based nutrition guidance. The notion that eliminating or replacing Easter candy will instantly improve a child's health or behaviour is not only completely unsubstantiated- it’s oversimplified, ignoring the overall quality of their diet.

Instead, parents should focus on the bigger picture. Building a diet rich in a variety of nutrient-dense foods as a foundation, with room to enjoy candy from time to time, is a more balanced and sustainable approach to promoting healthy eating habits. While following dietary guidelines and reducing UPFs is recommended, no foods should be completely off limits, and it’s unrealistic (and no fun) to expect children to skip their Easter treats.

Remember, you don't need 'clean candy' swaps for Easter if you're feeding your kids nutritious foods year-round. Balance and perspective are key to finding that ‘sweet spot’ between health and fostering a positive food environment for your children.

Remember that while shocking statements are very effective at creating engagement, they lack the nuance needed to fully grasp a topic. If you are worried about the overconsumption of sweet treats over the holidays, seek advice from a dietician or registered nutritionist.

A recent social media post claimed that swapping out popular Easter candies will “instantly” improve children’s behaviour and health. The post highlights four candies, labelled as “dangerous Easter candies” – Lindt chocolate bunnies, Nerds Gummy Clusters, M&Ms, and Sour Patch Kids jelly beans – saying they contain soy lecithin, Red 40, Blue 1, and corn syrup, which are said to be linked to serious issues like cancer, DNA damage, ADHD, diabetes, or metabolic problems. Here we fact-check each claim using scientific evidence and emphasise an important missing question: “In what context (amount and frequency) do these ingredients cause harm?”

Full Claim: “Stores sell sickness, inflammation, obesity, ADHD and advertise it as a celebration. It’s time to put your foot down and choose better alternatives. Your kid’s health and mood will change! Instantly.”

While some studies suggest links to health concerns in specific contexts (e.g., excessive consumption or sensitivities), there is no evidence that swapping these treats for healthier alternatives will instantly change a child’s behaviour. On the other hand, research shows that children associate food with feelings of guilt, pleasure, and health morality, and these associations can lead to restrictive or conflicted eating patterns.

Misinformation about food ingredients can create unnecessary fear among parents and lead to unrealistic expectations about dietary changes. More importantly, they distract from the real issues within our food system that impact public health.

Eddie Abbew’s claims on red meat: what you need to know

Final Thoughts

Eddie Abbew’s apparent dismissal of the available evidence on associations between high red meat intake and diabetes or heart disease highlights a misunderstanding of the scientific process. Similar misconceptions often get shared on social media when influencers discredit a single study on account that it does not prove causation.

Dr. Gil Carvalho explains how nutritional science works very clearly through his platform Nutrition Made Simple! The critical understanding he promotes is a valuable tool in the navigation of nutritional information on social media. In the following video (using red meat and cardiovascular disease risk as an example), he says that “the scientific process is about [...] a gradual reduction of uncertainty.”

He goes on to explain that “there is no such thing as the perfect experiment,” and that is why looking at the big picture is so important, particularly when considering long term, complex health outcomes. On the other hand, trials like the one Eddie Abbew jokingly suggests, where you feed one type of food to a population for one month, do not only pose ethical issues, they simply wouldn't answer the question: what is the health impact of this food?

In conclusion, while Eddie Abbew questions the link between red meat and disease, the scientific consensus supports moderating red meat consumption. For most, balancing meals with vegetables, whole grains, and plant proteins remains the best approach to reducing inflammation and chronic disease risk.

We have contacted Eddie Abbew and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Eddie Abbew’s statements came as an answer to a member of the audience. As his answer focused on inflammation, let’s start by detangling the links between red meat consumption, inflammation and diabetes, before addressing specific claims.

Type 2 diabetes, the most common form of diabetes, develops as a result of a combination of insulin resistance and pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction. Insulin resistance occurs when insulin-sensitive tissues like muscle, liver, and fat fail to respond effectively to insulin, while beta-cell dysfunction reduces the pancreas’s ability to produce sufficient insulin to compensate for elevated blood sugar levels.

The exact cause of these cells’ failure to secrete enough insulin is not fully understood. However, recent research has shown that inflammation might play a significant role in the development of diabetes and its complications (source). Inflammation refers here to chronic inflammation, that is to say long-term inflammation that lasts for prolonged periods of months or years, causing damage to tissues (source).

Claim 1: Eating Only Red Meat for a Month is the Best Way to Reduce Inflammation

Eddie Abbew starts by suggesting that eating only red meat for a month is the best way to reduce inflammation.

Fact-Check: Diet changes can help to minimise inflammation. However, there isn’t one single food that can help to reduce inflammation; instead, experts often recommend focusing on healthy eating patterns. One good example is the Mediterranean Diet, which has been associated with lower levels of inflammation (source).

Elimination diets often leave people feeling better because they are removing other foods which may be causing discomfort, like processed foods, refined sugars, and potential dietary triggers (like gluten or Fodmaps), rather than them actually benefiting from the meat. This can give them a false sense of cause and effect.

So what about red meat? Some studies show that red meat is not inherently inflammatory (source). However, while short-term consumption may not immediately trigger inflammation, Eddie Abbew’s answer ignores the long-term risks of chronic inflammation and diabetes linked to habitual (and excessive) intake. A one-month red meat diet excludes essential nutrients like Vitamin C, folate, or fibre. It also excludes important dietary sources of antioxidants and polyphenols, compounds found in plant foods that are known to help reduce inflammation.

Eddie Abbew’s suggestion overlooks balance and the risks associated with over-consumption. When it comes to red meat, dose matters (source). Indeed studies show that greater consumption of processed and unprocessed red meats is associated with a greater risk of type 2 diabetes. In the UK, the NHS advises people who currently eat more than 90g of processed or unprocessed red meat per day to reduce it to 70g (source).

Claim 2: Red Meat Does Not Cause Diabetes or Heart Disease

Eddie Abbew challenges the idea that red meat consumption is linked to diabetes and heart disease, suggesting that there is no real proof. By saying that “it’s all lies”, he doesn’t deny that there are studies showing a link; rather the implication seems to be to disregard them because they do not offer real evidence.

Fact-Check: A close look at all of the evidence available first shows us that this is a very complex question. While there isn’t a single study that proves a definite causal link, this doesn’t mean that there is no reasonable evidence to support that limiting red meat intake, particularly when swapped with plant-based proteins, can decrease the risk of developing type 2 diabetes or heart disease.

Numerous studies have consistently shown that both unprocessed and processed red meat are associated with a higher risk of these conditions. For example, a 2023 Harvard study of 216,695 participants found that each daily serving of processed red meat (e.g., bacon) increased diabetes risk by 46%, while unprocessed red meat raised it by 24% (source). A meta-analysis of 4.4 million people confirmed these associations (source).

Strength of evidence

There are several factors to take into account here, among which: consistency across populations and study types; biological plausibility; and adjustments of variables. Together, these can help us increase our confidence in the findings showing an association between red meat intake and disease risk.

- Consistency

One way of increasing our certainty levels about the health impact of a food is when results from observational studies are repeated across different study types and populations. This helps to reduce the likelihood that preliminary results might have been accidental.

This is what a recent meta-analysis published in The Lancet aimed to address: it included data from 31 cohort studies across 20 countries, and showed similar trends, with a greater impact from processed red meat.

Conversely, there are studies, including recent Mendelian randomization studies, which have found no causal relationship between red/processed meat and diabetes or cardiovascular disease (source). Looking at the big picture of the available evidence, it is important to remember that what red meat is replaced with makes a difference. For example, substituting red meat with plant-based proteins (e.g., legumes, nuts) has been shown to reduce diabetes risk (source).

- Biological Plausibility

The second factor is biological plausibility. This refers to the idea that a scientific hypothesis or theory is consistent with current known mechanisms underlying a particular phenomenon. In other words, are there mechanisms that could explain why that food might increase or decrease the risks of developing a disease?

Red meat contains heme iron and compounds like glycine, which may promote insulin resistance and oxidative stress. Processed meats also often include preservatives (e.g., nitrates) linked to inflammation and beta-cell dysfunction (source), and contain saturated fats, which can raise LDL cholesterol levels and increase cardiovascular risk.

Although these remain hypotheses, what we can see here is that there are mechanisms which align with results from observational studies showing an association between a higher intake of red meat and the development of chronic diseases.

- Adjustments of variables

Finally, adjustments of confounding variables help researchers to understand if it is indeed consumption of the food in question causing the observed result, or rather another factor (like physical activity or lack of; habits like smoking; health background of participants, low fibre intake, etc.)

That is why studies use statistical analysis to control for such confounders.

Claim 3: The people who come up with [claims that red meat causes diabetes or heart disease] are the ones selling you ultra-processed foods

Fact-Check: No study definitely proves a causal link between eating red meat and chronic disease, but many show strong associations. Together, these studies form the basis of dietary guidelines. These guidelines are not promoted by food companies selling ultra-processed products; they are promoted by health agencies, as well as charities supporting patients who suffer from these conditions.

Dietary guidelines do not focus exclusively on red meat. They advise limiting red meat consumption, while acknowledging it as a source of essential nutrients (source). But they also very clearly advise the public to limit consumption of ultra-processed foods, which the NHS says “are not needed in our diet, so should be eaten less often and in smaller amounts” (source).

When someone suggests you should “do the opposite of mainstream advice,” as Eddie Abbew does in the Instagram caption, it’s a major red flag. This kind of messaging is designed to create an us vs. them narrative, implying that health professionals, researchers, and public bodies are somehow working against you. It's a common tactic used to make diet trends seem rebellious or “truth-revealing,” when in fact, it undermines decades of rigorous, peer-reviewed research.

While it may not be trendy or exciting, advice like "eat more vegetables, whole grains and fibre-rich foods" is mainstream advice because it works. It's built on enormous bodies of evidence which can be replicated across populations and study types.

It’s also worth noting that red and processed meats are among the few foods the World Health Organization has classified as carcinogenic. This classification is not alarmist — it’s based on substantial and credible evidence.

In an age of social media noise, critical thinking and evidence literacy are more important than ever. Sensational claims should always be weighed against the strength of the evidence behind them — not just how confidently they’re delivered.

When evaluating dietary claims, rely on peer-reviewed studies and systematic reviews rather than anecdotal evidence or unproven methods. Be cautious of simplistic or dismissive claims about established research findings.

In a recent video posted on Instagram, Eddie Abbew questions the link between red meat consumption and the risk of diseases such as diabetes and heart disease. He suggests that claims about red meat causing these conditions are unfounded and challenges the idea that eating only red meat for a month could lead to health issues.

Full Claim: “The best way to reduce inflammation is to eat red meat, red meat only for about a month. It's all lies. Can you show me anyone that can prove that red meat gives you heart disease? What, they followed somebody eating just red meat for a whole month and say, oh you got that from red meat, it's so bullshit. The people who come out with that, they're the ones who are selling you ultra-processed foods”

Scientific evidence consistently associates higher red meat intake, especially processed varieties, with increased risks of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

830 million people are estimated to live with diabetes globally, and dietary misinformation risks undermining prevention efforts.

Seed oils are in baby formula for a reason. Here’s why it matters

Final Thoughts

This type of messaging is likely to trigger fear among a vulnerable population: parents of young children. While breastmilk remains the most beneficial method of feeding infants, there are many reasons why breastfeeding might not be possible, and messaging that stigmatises bottle feeding can negatively affect parental mental health and discourage the use of safe feeding options.

Seed oils are safe for consumption and provide essential nutrients crucial for infant growth, making them an integral part of regulated formulas. Parents should consult healthcare professionals for accurate guidance on infant nutrition rather than relying on social media claims.

Check out this guide to help you navigate nutrition information online, and to better understand what to watch out for when an author claims their argument is supported by a study.

We have contacted Dr. Paul Saladino and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Claim 2: Infant formula contains a lot more oxidised lipids than breast milk

Fact-Check: Saladino states that this has been “clearly shown” and cites a study that found higher levels of oxidised lipids (like 4-HHE and 4-HNE) in formula compared to breast milk (source). This statement lacks crucial context needed to address the implication that it has also been “clearly shown” that the level of oxidised lipids in formula is detrimental to a baby’s brain development.

Firstly, oxidation is a natural process in all fats. Fats oxidise when they’re exposed to heat, light, or oxygen for extended periods—this can happen during processing or storage. While some oxidised fats can form compounds that may cause harm in high amounts, infant formula is carefully regulated and includes antioxidants like vitamin E to mitigate this (source). It is important to remember that infant formula is one of the most regulated food products globally. Strict guidelines ensure that levels of contaminants and oxidation products remain within safe limits. Formulas are also continually reformulated to improve lipid stability (source).

Secondly, the cited study did not establish a causal link between oxidised lipids and harm to infant brain health.

Scientific Consensus: On the other hand, the evidence supports that infant formulas can effectively assist a baby’s development and health, offering a valuable alternative to mothers who cannot breastfeed.

Research also suggests nutrient-enriched formulas that closely mimic breast milk “in lipid composition as well as structural properties of lipid droplets during infancy may positively affect cognitive outcomes during childhood” when compared with standard formula (source).

Claim 1: [Seed oils] are a train wreck for your baby’s brain.

Fact-Check: The claim lacks scientific evidence. In fact, the use of seed oils in infant formula has the opposite effect.

Seed oils such as sunflower and soybean oil are added to formula to provide essential omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids critical for brain development. Blending vegetable fats allows to mimic the composition of breast milk as closely as possible (source, source).

Scientific Consensus: Fats are vital for infants, providing up to half their energy needs during early development (source).

A review concluded that blending vegetable and bovine fats might create optimal formulas for infant health (source). The researchers also note that despite its benefits, fats derived from dairy are not sufficient to cover all lipid (fat) needs for infants. For example, it contains high levels of saturated fats and low levels of long-chain fatty acids (such as omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids) when compared to breast milk. Seed oils and oils derived from plant sources are generally higher in these types of lipids and are a good complement to dairy fats to achieve a mix that most resembles breast milk. This contradicts Saladino’s suggestion that all seed oils should be removed from formulas.

.avif)

Exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life is the best option for infant development, growth and immunity. However, for parents who are unable to breastfeed, there are many viable options for breastmilk substitutes on the market, commonly known as infant formula. This formula is just that - a mix of ingredients designed to mimic breastmilk’s nutritional profile as closely as possible, including its fat content. This means combining multiple sources of lipids (fats), including seed oils which are higher in poly-unsaturated and long-chain fatty acids than dairy, to achieve the optimal lipid ratio.

Did you know that cow’s milk is not recommended as a beverage for infants under the age of 12 months? Because of its composition in fats, protein and minerals, cow’s milk is not an appropriate substitute for breastmilk or infant formula at this age. Infants’ kidneys are still developing in the first year of life and the high mineral and protein content in cow’s milk is difficult for them to process and could lead to health complications (source, source). Whole milk can safely be introduced after 1 year.

When evaluating claims about infant nutrition, prioritise peer-reviewed studies and guidance from paediatric organisations over social media influencers.

Dr. Paul Saladino claims that seed oils in infant formula are “a train wreck” for a baby’s brain health. He suggests that there is clear evidence that these oils are detrimental to infant developing brains and urges for changes to be made to formula compositions. We bring you a reality check by reviewing the evidence on infant formula and baby development.

Full Claim: [Seed oils] are a train wreck for your baby’s brain. We know that 55-66 percent of infants are fed formula. Breast milk is obviously best but if you’re feeding infant formula to your baby, you need to know that this contains 25 to 275 times more oxidised lipids [...] This is the problem with these infant formulas, they’re full of seed oils. This is not great for infant developing brains to have seed oils and oxidised lipids at that level in infant formula.

Seed oils are a regulated source of essential fatty acids required for a baby’s growth and development.

Misinformation about infant nutrition can cause unnecessary parental anxiety and lead to avoidance of safe feeding options. A balanced understanding is critical, as formula provides vital nutrients for infants who cannot be breastfed.

Omega-3 fatty acids: evaluating the role of fish and plant sources

A closer look at supplements

In some cases, supplements might be recommended to help manage or prevent certain health conditions. They can also be used during pregnancy to support foetal brain and eye development. The dosage and necessity of supplementation should be tailored to individual health needs and discussed with a healthcare provider to ensure safety and efficacy.

When choosing supplements, it’s helpful to understand the differences between fish oil, cod liver oil, and omega-3 supplements. Fish oil is derived from the tissues of fatty fish such as salmon or mackerel and is rich in omega-3 fatty acids, primarily EPA and DHA, which support heart, brain, and joint health. While fish oil has become a popular supplement, it is worth noting that studies have found that many common omega-3 fish oil supplements are rancid, which can lead to reduced efficacy and potential health risks (source).

Cod liver oil, on the other hand, is extracted specifically from the liver of codfish and contains not only EPA and DHA but also vitamins A and D, making it a nutrient-dense option for those needing additional vitamin support. However, due to its high Vitamin A content, it is not recommended during pregnancy (source).

Meanwhile, omega-3 supplements may be plant-based or derived from marine sources and typically focus on delivering ALA, EPA, or DHA individually or in combination.

What if I want to protect the environment?

In her book The Science of Plant-Based Nutrition, Registered Nutritionist Rhiannon Lambert notes that while “fish can be a healthy addition to a plant-based diet if consumed in the right quantities,” “sadly times are changing quickly and the quality of fish in the oceans is not as good as it once was.”

Beyond health considerations, it’s important to mention sustainability concerns in order to get a bigger picture of the impact of fish consumption and make informed decisions.

Fish production, both through fishing and aquaculture, presents several environmental challenges, including overfishing, habitat destruction, and pollution.

So what can we do to address these concerns?

If you want to include fish to your diet, you can start by adhering to portion recommendations. These are not only important to ensure that we meet nutritional needs, but also to ensure that fish production remains sustainable by not overconsuming it.

In the UK, the NHS advises to include 2 portions of fish a week, one of which should be oily fish. This is because oily fish is particularly rich in EPA and DHA. One portion of fish is approximately 140g.

The advice is to focus on sustainable sources, but also on consuming a variety of fish, especially less common species.

Final Thoughts

When evaluating claims that one food is superior to another, we need to consider individual needs and preferences to make an informed decision. However, social media trends that demonise various foods are detrimental because they do not take into account the role played by these foods on a global scale.

While it is perfectly possible to meet nutritional requirements without eating fish, fish can provide an essential source of nutrients including vitamins, minerals, essential fatty acids and protein for people who don't have regular or easy access to foods such as flaxseeds, chia seeds, and oils. As a result, it can play an important role in supporting food security by providing essential nutrients that help combat malnutrition and support healthy development, particularly in vulnerable populations (source).

The notion that there is a single "right" way to eat, as is often portrayed on social media, is misleading, as dietary needs vary greatly among individuals. Social media often oversimplifies these complexities, but it's essential to recognise the diverse benefits of different food sources. By acknowledging these nuances, we can foster a more inclusive and informed approach to nutrition, one that respects both personal choices and global health imperatives.

This article was updated on April 29th to add some nuance about the conversion of ALA into EPA or DHA, taking into account the omega 3/omega 6 balance. We are working on a guide to dive deeper into this complex topic.

We have contacted Barbara O’Neill and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Which Source of Omega-3s is “Superior”?

O’Neill suggests that there are better omega-3 sources than fish oil, and that “you can get your omega-3 by foods, by plant foods.” But this depends on many factors, which we discuss below. The answer will depend upon an individual’s personal preferences and what matters to them. It also depends on what question we’re asking. Are we thinking about health outcomes, environmental sustainability concerns, ethical issues, or something else?

What if I Don’t Eat Fish?

Because EPA and DHA are associated with many health benefits, particularly heart health, people might worry about the low or non-consumption of fish. There are various reasons why some individuals cannot or choose not to consume fish or seafood products. These can range from personal dislikes, food allergies, ethical or environmental concerns.

According to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, a diet that doesn’t contain fish can be “nutritionally adequate and offer long-term health outcomes associated with cardiometabolic diseases” (source).

For individuals who don't consume fish, obtaining sufficient EPA and DHA can be managed by making sure you get plenty of ALA-rich foods in the diet, like flaxseed, chia seeds, walnuts, and oils, such as rapeseed and linseed.

Some fortified foods can also provide us with omega 3s. These include eggs, milk, yogurts, and plant-based milks. You can also get EPA/DHA from algae oils. However, recent research suggests that “the rate of ALA conversion may be sufficient to maintain adequate DHA levels through plant-sourced ALA consumption alone, although more research is warranted" (source).

The best thing to do is to consult a doctor, dietitian or registered nutritionist to advise as to whether supplementation is necessary.

The emphasis remains placed on a well-planned, varied, and nutrient-dense plant-based diet, rather than sole reliance on supplements.

There are Different Types of Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Before diving into the claims, it's important to understand what omega-3 fatty acids are, and that not all omega-3s are the same.

A fatty acid is a building block of fats, kind of like how bricks make up a wall. Fatty acids are found in fats and oils and are essential for many body functions.

Omega-3 fatty acids are a specific type of fatty acid that our bodies can’t make on their own, which is why they’re called essential fatty acids. We have to get them from our diet. There are three main types that are important for human health:

- Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA): Primarily found in plant sources like flaxseed, chia seeds, and walnuts (source).

- Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA): Primarily found in marine sources like fatty fish (salmon, mackerel, sardines) and algae (source; source).

EPA and DHA are considered the most bioactive forms of omega-3 and provide the most direct health benefits. For example, they play essential roles in cardiovascular health, brain health, and eye health. In particular, DHA is critical to a fetus' development (source).

Claim 1: “And yet no creature can put Omega-3 into their fatty acid chain, only plants can. So why are fish so high [in Omega-3]? Because fish are eating a one-celled algae that [contains it].”

This claim appears to suggest that only plants can create omega-3 fatty acids, which is mostly accurate. Microalgae (not all plants) are the primary organisms in nature that can make omega-3 fatty acids from scratch. These single-celled organisms are the foundation of the marine food chain and the original source of omega-3s.

Land plants can produce one type of omega 3, ALA, but generally cannot produce EPA and DHA directly. Animals, including fish, cannot synthesise omega-3s from scratch and must obtain them from their diet. Fish obtain EPA and DHA by consuming algae, or smaller fish that have consumed microalgae.

Claim 2: “Flaxseed is the highest source of Omega-3” and “Chia seeds is the second highest source of Omega-3.”

Research suggests that flaxseeds tend to have a slightly higher omega-3 content than chia seeds. However, depending on what you read, some sources may write that chia seeds have a higher omega-3 and/or ALA content, such as this recent review of chia seeds, contradicting the ranking in the claim.

But the main reason why the claim is misleading, is that it does not take into account that there are different forms of omega 3:

While flaxseed and chia seeds are great sources of ALA omega-3s, some fish, such as mackerel, are higher in the other omega-s DHA and EPA. Therefore, the implication that fish’s reputation for being high in omega-3 is overstated is misleading, because it overlooks the role played by EPA and DHA.

The human body can convert ALA into EPA and DHA, but only in small amounts: approximately 5-10% of ALA gets converted to EPA and less to DHA (source). This means that while flaxseed is a good source of ALA, it doesn't necessarily translate to higher levels of EPA and DHA in the body.

The body's conversion of ALA into EPA and DHA may also be lowered by high consumption of omega 6 fatty acids, as they compete for the same pathways when they are broken down.

While dietary recommendations provide clear guidance on meeting DHA and EPA requirements through oily fish consumption, there is less clarity when it comes to achieving similar levels from plant-based sources due to the body’s limited ability to convert alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) into these long-chain omega-3 fatty acids.

For individuals on plant-based diets, algae-based supplements can be a valuable option to maintain adequate omega-3 levels.

Foods offer more than just their individual nutrients—they bring unique benefits to the table. Both oily fish and plant-based sources like chia and flax seeds provide valuable omega-3 fatty acids, but there’s no need to pit them against each other.

Fatty fish not only deliver a quick, affordable source of protein but also offer a rich supply of vitamin D—especially when consumed with the bones. Meanwhile, chia and flax seeds are excellent for boosting fibre intake and can easily be added to smoothies and baked goods.

Whether or not you follow a plant-based diet, incorporating seeds into your diet can have nutritional benefits.

Influencers often claim that some foods are superior to others, but context matters. Look for information that considers multiple perspectives.

In a recent social media post, Barbara O’Neill makes several claims about the best sources of omega-3s in the diet. She states that “you can do superior to fish oil” and that “flaxseed is the highest source of omega-3”.

Full claim: “What are we told is the highest source of Omega-3? Fish? And yet no creature can put Omega-3 into their fatty acid chain, only plants can. So why are fish so high? Because fish are eating a one-celled algae that is high, so you can do superior to fish oil, you can get your omega-3 by foods, by plant foods. Flaxseed is the highest source of Omega-3, flaxseed and linseed are basically the same thing; Chia seeds is the second highest source of Omega-3.”

While flaxseed is high in one type of omega-3 (known as ALA), fish is a good source of two other types of omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA). Only plants create omegas from scratch, and this is where fish get their omega 3s.

Understanding the sources and types of omega-3 fatty acids is important for making informed dietary choices, regardless of dietary preferences. Additionally, clarifying the role of fish and plant sources in providing omega-3s helps address misconceptions about their nutritional benefits and environmental implications, impacting both personal health decisions and broader discussions on sustainable nutrition.

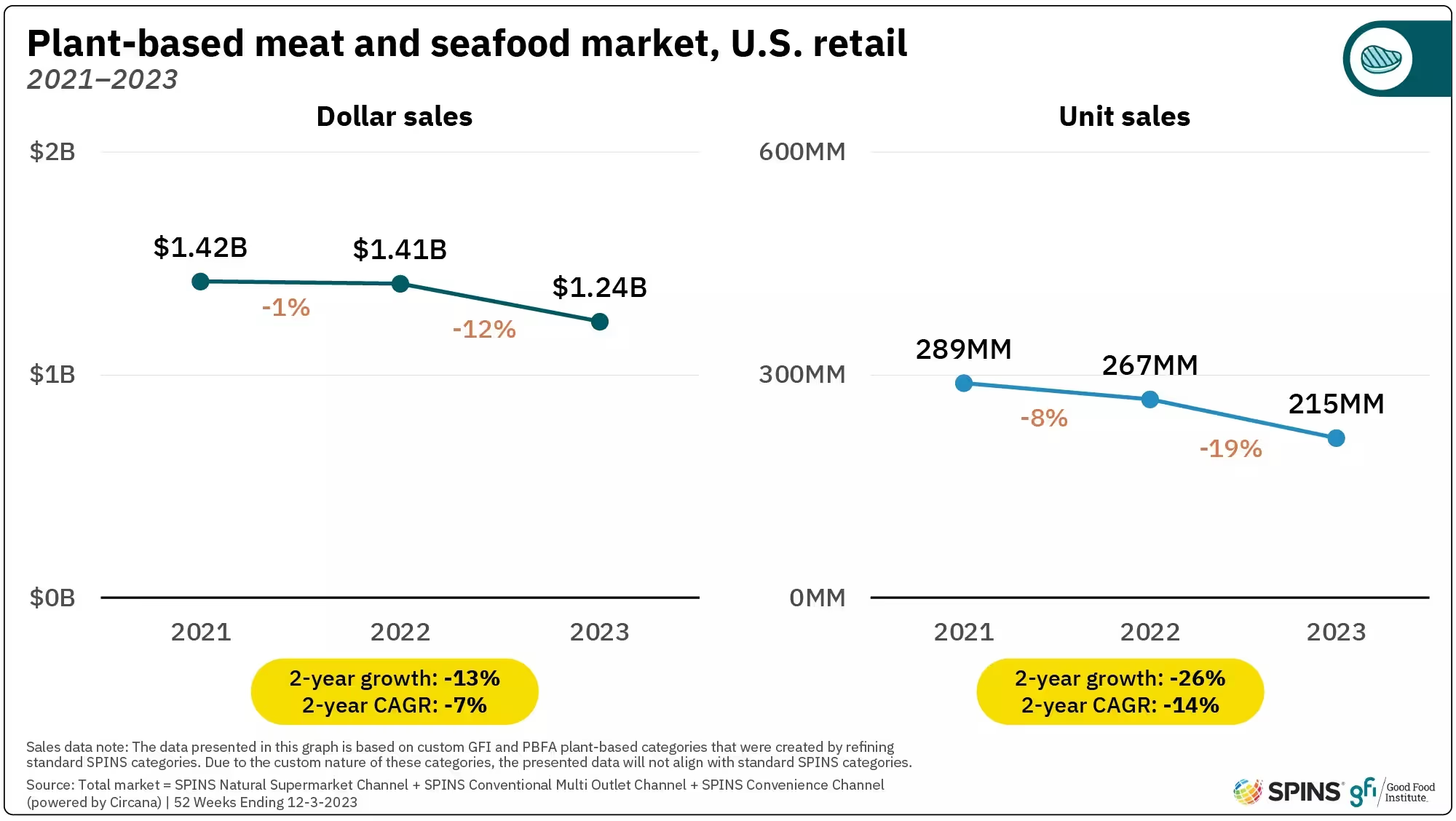

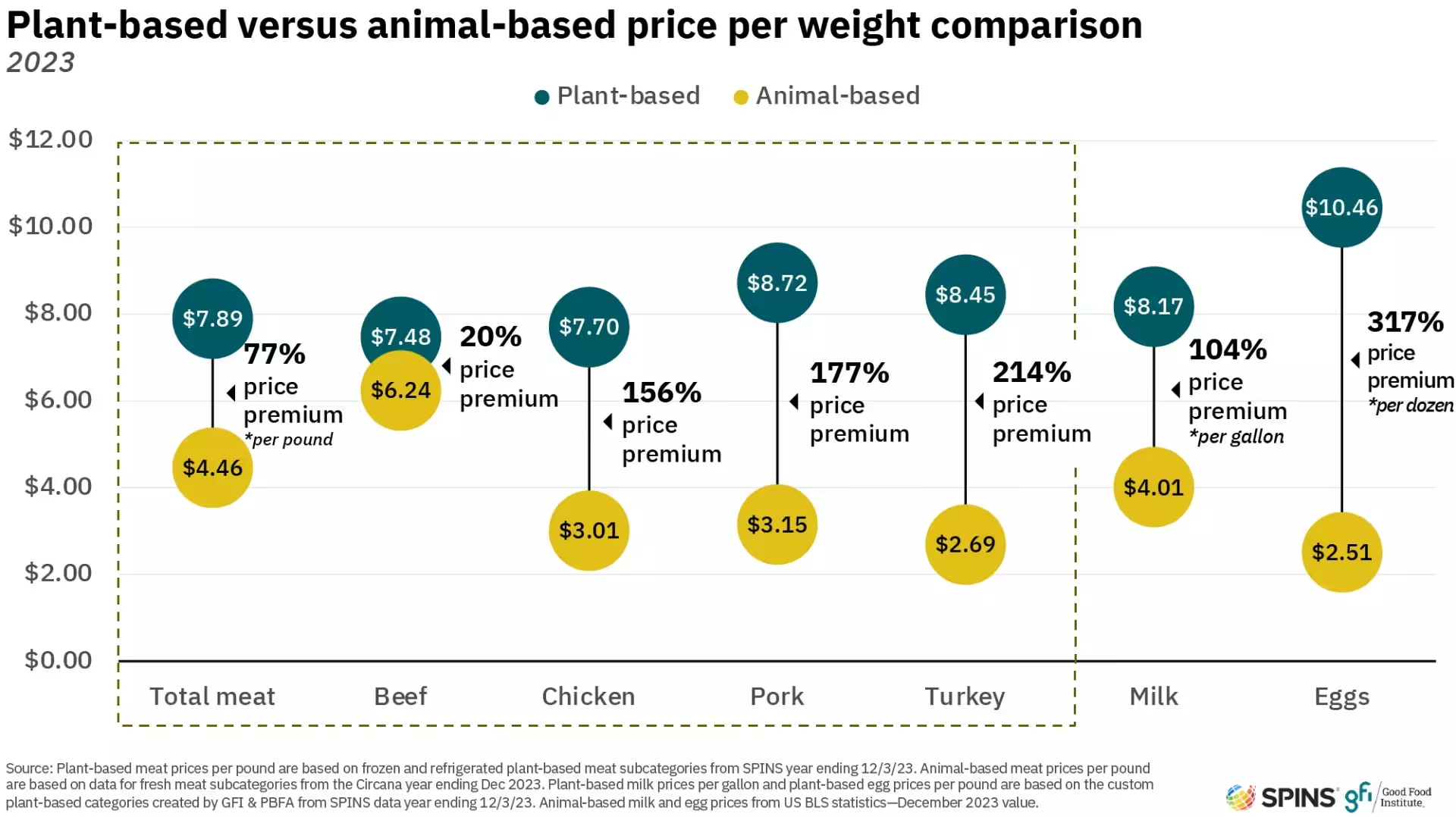

Unpacking the shift: why consumers are moving away from plant-based meat

There’s been a lot of talk lately about the decline in plant-based meat sales, with some suggesting that it signals reduced interest in plant-based eating altogether. But is this really the case? A closer look at the data and consumer trends suggests a more nuanced reality—one that speaks more to market shifts than a wholesale rejection of plant-based foods.

The Bigger Picture

It’s true that U.S. retail sales of plant-based meat products fell by 12% in 2023, and in the UK, sales dropped by 13.6%. Some media outlets have taken this as proof that the broader plant-based movement is fading. However, focusing solely on these numbers ignores the fact that consumer preferences are shifting, rather than disappearing.

While some plant-based meat alternatives have struggled, the demand for alternative proteins remains. Other sectors, such as plant-based dairy and whole-food plant proteins, continue to grow. For example, the global tofu market was valued at $2.8 billion in 2023 and is projected to reach $4.3 billion by 2032. This suggests that consumers are still open to plant-based options but are becoming more selective about what they buy.

Why Are Sales Declining?

One reason for the dip in plant-based meat sales is that many products have not met consumer expectations. We've all tried a plant-based product that has disappointed with taste and texture, while other alternatives are priced higher than their conventional counterparts. In a time of economic uncertainty, cost is a major factor in purchasing decisions, and many consumers are opting for more affordable protein sources—whether that means traditional meat, whole plant foods, or other alternatives, such as tempeh.

Another key factor is health perception. Some consumers who initially embraced plant-based meats are now scrutinizing ingredient lists, wary of ultra-processed products. This has led to a growing preference for less processed plant-based options like beans, lentils, and vegetables, which remain affordable and widely available.

Moreover, there are an increasing number of social media influencers that are breaking down the barriers to cooking with less processed forms of plant-based protein, either by creating accessible recipes or simply normalising the concept of eating beans with every meal, such as members of the leguminati.

Is This Just a Trend?

It’s easy to assume that plant-based eating was simply a passing trend fuelled by social media, but the reality is more complex. The rise of alternative proteins has been driven by multiple factors, including environmental concerns, health considerations, and ethical debates. While social media helped popularize these products, consumer interest in sustainable food choices predates the recent boom in plant-based meat alternatives.

"What we’ve really come to understand is just how important capability is when it comes to reaching the mass market. There’s a clear appetite—many people genuinely want to cut down on meat—but a big barrier is they simply don’t know how to start. For whatever reason, the products we have on shelves right now aren’t quite connecting. And that’s surprising, because plant-based meats are actually super easy to cook—much easier than animal proteins, which need careful handling and have a shorter shelf life. The good news? There’s huge potential here. Once we crack that awareness gap, the category has real room to grow." - Indy Kaur, Founder - Plant Futures

Trends should also be studied over a long time, rather than across a couple of years. It would be normal to expect fluctuations in any industry's growth, particularly in a time of such geopolitical instability. Basing bold claims about the decline of an industry after just two years of market shift seems disingenuous.

What’s Next for Alternative Proteins?

Rather than signalling the end of plant-based eating, this shift in sales reflects an industry in transition. Companies that adapt by improving taste, affordability, and nutritional transparency will likely find continued success. Meanwhile, consumer demand for diverse protein sources—including traditional meat, plant-based options, and emerging alternatives like cultivated meat—is shaping a more dynamic food landscape.

For policymakers, businesses, and consumers, the key takeaway isn’t that plant-based eating is disappearing, but that it is evolving. As the market matures, the focus is moving away from novelty and toward quality, affordability, and choice. Whether people choose plant-based foods for health, environmental, or ethical reasons—or prefer traditional protein sources—the future of food is likely to be more inclusive and diverse than ever before.

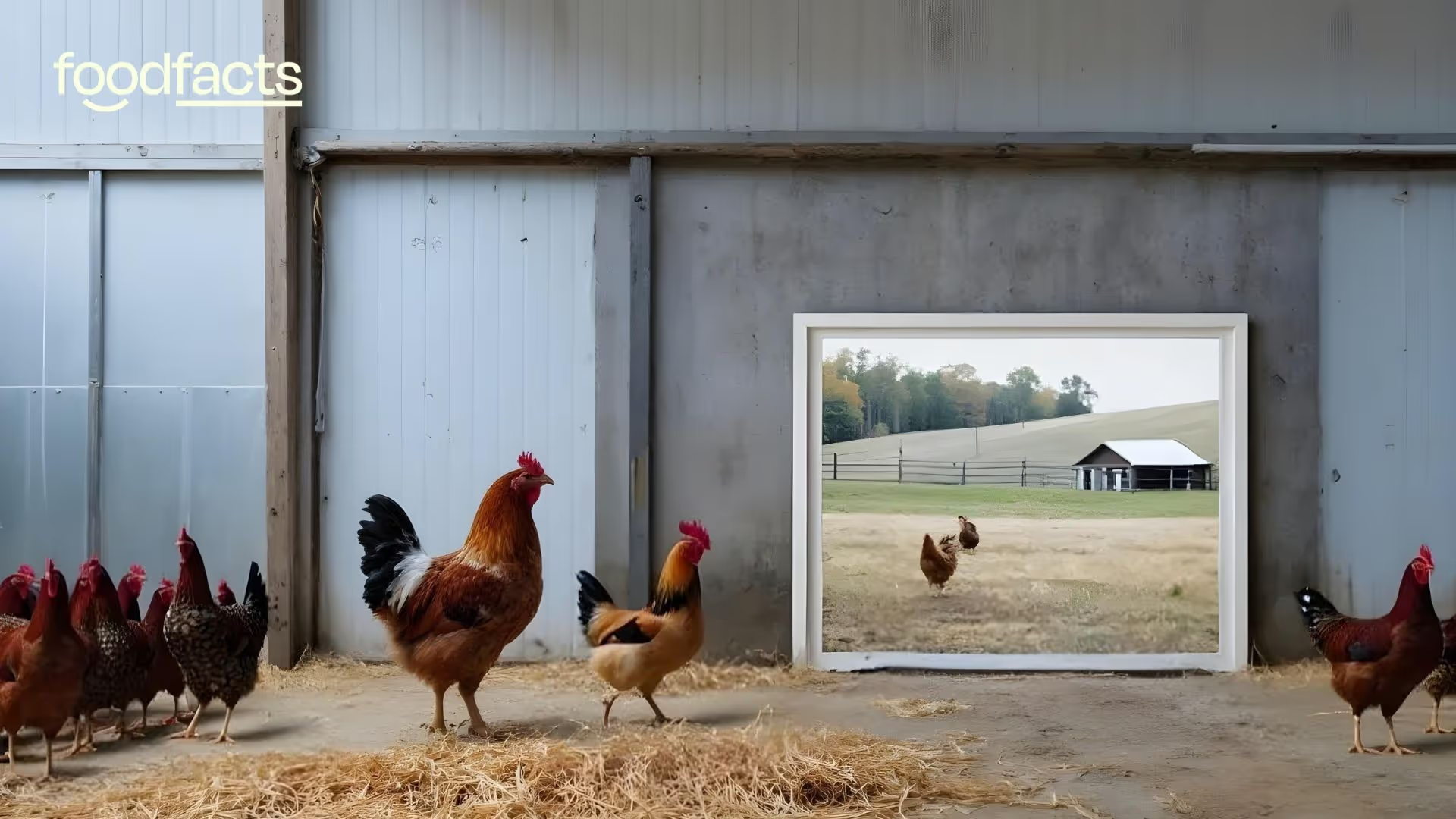

What do egg prices have to do with pandemics? Understanding the bird flu crisis

The price of eggs has skyrocketed in recent months, leaving many consumers shocked at checkout counters across America. This dramatic increase is not simply due to general inflation, but rather points to a much more concerning issue with potential global implications. The current egg shortage and price surge are directly linked to a widespread bird flu outbreak that has devastated poultry farms, and some experts worry this situation represents more than just an economic inconvenience—it could signal pandemic risks that echo historical disasters like the 1918 Influenza Pandemic. Understanding this connection helps consumers make sense of not only why their breakfast costs more, but also how our food systems are interconnected with public health security.

The Recent Egg Price Crisis

The numbers tell a startling story about what's happening to egg prices. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average cost of a dozen large, Grade A eggs has risen from $2.52 in January 2024 to a record-high $4.95 in January 2025. This represents a dramatic 53% increase in just one year, far outpacing overall food inflation, which rose just 2.5% during the same period. Despite a recent decrease in the price of wholesale eggs, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) projects that egg prices will continue to climb, potentially increasing by more than 40% throughout 2025. For the average family, this means eggs—once considered an affordable protein source—have become a significant budget consideration.

"While consumer choice is important, it's only one piece of the puzzle. We need to address the vulnerability of our food systems by advocating for federal regulatory action, improved tracking, and a systemic shift towards climate-resilient farming that prioritizes habitat protection and disease prevention, ultimately safeguarding us from future pandemics" - Dr Jennifer Molidor

This price surge stems directly from a widespread outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), commonly known as bird flu. The current strain, H5N1, has proven particularly devastating to poultry populations. In December 2024 alone, outbreaks resulted in the "depopulation" (a term used to describe the necessary culling of infected and exposed birds) of 13.2 million birds, according to USDA data. Since October, when the latest wave of outbreaks began, more than 52 million egg-laying hens have been affected across ten states, including Arizona, California, Indiana, Iowa, Missouri, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Utah, and Washington. To put this in perspective, these losses represent approximately 17% of the total U.S. egg-laying hen population in just four months. The fourth quarter of 2024 was particularly devastating, with more than 20 million egg-laying chickens lost to the virus—marking the worst toll on America's egg supply since the outbreak began.

How This Affects Your Shopping and Dining Experience

The effects of this crisis extend beyond just higher prices at the grocery store. Many retailers have implemented egg purchase limits to prevent stockpiling and ensure fair distribution. Major chains including Trader Joe's, Costco, and Sprout have restricted the number of egg cartons customers can buy. Shoppers in some regions have encountered completely empty egg shelves, particularly for cage-free and organic varieties, which have been disproportionately affected by the outbreak. Despite representing only about a third of U.S. egg layers, cage-free hens accounted for nearly 60% of all bird flu cases in 2024.

The impact extends to restaurants as well. In February, Waffle House—an American breakfast staple—announced a 50-cent surcharge for each egg ordered due to the shortage and price increases. "While we hope these price fluctuations will be short-lived we cannot predict how long this shortage will last," the chain stated in a press release. Many other restaurants have either raised prices, reduced egg-heavy menu options, or looked for alternatives to manage costs.

Government officials are implementing various measures to address the shortage. Nevada's Department of Agriculture temporarily suspended state laws requiring eggs to be cage-free and allowed the sale of Grade B quality eggs, which are typically used in processed food products rather than sold directly to consumers. In New York, Governor Kathy Hochul ordered the closure of live bird markets after the virus was detected in seven markets across New York City. These emergency measures highlight the severity of the situation.

Beyond Your Breakfast Plate: A Spreading Threat

The bird flu crisis extends far beyond just chickens and eggs. Since 2024, the H5N1 strain has spread to dairy cows, raising additional concerns about food security and public health. 17 states have now reported cows infected with H5N1, which kills around 2% to 5% of infected dairy cows and can reduce a herd's milk production by 10% to 20%. This expansion to mammals represents a concerning evolution of the virus, as each new species provides opportunities for the virus to mutate and potentially become more dangerous to humans, as well as to other wildlife and endangered species.

While it is reported that the health risk to most able-bodied people remains low at present, the situation requires careful monitoring, particularly for people living in vulnerable communities with inadequate testing and reporting. Several human cases of bird flu have already been reported, primarily among farm workers with direct exposure to infected animals. Public health experts note that the virus continues to "surprise" them with its ability to adapt and spread, emphasizing that the risk assessment "could change, and could change quickly". Food safety experts reassure consumers that properly cooked eggs and poultry remain safe to eat, as normal cooking temperatures (heating foods to at least 165 degrees) destroy the virus along with other common pathogens like Salmonella.

The current situation draws concerning parallels to historic pandemics. The most notable comparison is to the 1918 influenza flu pandemic, which represents one of the deadliest disease outbreaks in human history. Estimates of the death toll from that pandemic vary considerably. Early estimates from 1927 put the figure at 21.6 million deaths worldwide. More recent reassessments in 2018 estimated about 17 million deaths, though other studies suggest the number could be much higher—between 50 million and 100 million. In India alone, the 1918 influenza pandemic flu killed between 12 and 14 million people, making it the only census period (1911-1921) in which India's population decreased. The devastating impact of that pandemic serves as a sobering reminder of what can happen when novel influenza viruses spread unchecked through human populations.

The Economic Ripple Effects

The financial impact of the bird flu crisis extends throughout the food system. Since 2022, the USDA has invested more than $1.7 billion in combating bird flu on poultry farms, including reimbursing farmers who have had to cull their flocks. An additional $430 million has been spent addressing the spread to dairy farms. In February 2025, the Trump administration announced a new $1-billion plan aimed at fighting the virus and ultimately bringing down egg prices. Most of these funds are earmarked for providing relief to affected farmers and expanding biosecurity measures at egg-laying facilities, with about $100 million dedicated to vaccine research and exploring egg import options.

For farmers like Brian Kreher, a fourth-generation egg producer in New York, the outbreak has created existential challenges. "Egg farmers are in the fight of our lives and we are losing," he told the BBC in a February interview. Many farmers face impossible choices, such as whether to accept chicks from areas near virus hotspots, knowing the risks but also understanding that without new birds, their operations would slowly cease to exist.

The impact extends to food manufacturers that rely on eggs as ingredients. Companies producing everything from baked goods to mayonnaise face higher production costs, which inevitably get passed on to consumers. Some businesses are exploring alternatives, creating potential opportunities for plant-based egg substitutes. For example, sales of plant-based egg alternatives jumped significantly in January 2025 compared to the previous year, according to reports from companies in this space.

What This Means for Consumers

As consumers navigate this challenging situation, understanding the connection between bird flu, egg prices, and potential pandemic risks helps inform both shopping decisions and broader perspectives on food systems. In the short term, expect egg prices to remain high and possibly increase further until poultry producers can rebuild their flocks—a process hampered by the ongoing virus circulation. Regional variations in price and availability will continue, with states that mandate cage-free eggs likely experiencing more severe shortages and higher prices.

For those looking to manage food budgets during this crisis, consider exploring recipes that use egg alternatives, or cook food that doesn’t require eggs at all. Tofu, legumes, and other plant proteins can also serve as nutritious alternatives in many recipes.

Food safety policy remains paramount. While bird flu virus particles have been detected in some dairy products, such as raw milk and cheeses, the FDA has reassured consumers that the commercial milk supply remains safe, particularly when pasteurized. This highlights the importance of pasteurization—not only for preventing bird flu transmission but also for eliminating other harmful pathogens that can thrive in raw milk. As already fact-checked by Foodfacts.org, raw milk can harbor dangerous bacteria such as Salmonella, E. coli, and Listeria, which pose significant health risks, especially to children, pregnant women, and those with weakened immune systems. Similarly, properly cooking eggs and poultry eliminates any potential virus risk. Continuing to follow standard food safety practices—such as thoroughly cooking animal products, avoiding cross-contamination, and washing hands after handling raw ingredients—provides protection against not only bird flu but also a wide range of more common foodborne pathogens.

The Bigger Picture: Food Systems and Pandemic Risk

The current bird flu crisis illuminates the complex relationship between agricultural practices, food security, and public health. Intensive animal agriculture, while efficient at producing affordable protein, also creates conditions that can facilitate disease spread. High-density housing of birds, long-distance transportation of animals, and the genetic uniformity of commercial flocks all contribute to vulnerability when pathogens emerge.

Some experts suggest that improving animal welfare and hygiene conditions, reducing flock density, and shortening supply chains could help mitigate future outbreak risks. These approaches may increase production costs but could prove far less expensive than managing widespread disease outbreaks after they occur.

The ongoing situation also highlights the importance of robust pandemic monitoring and response systems. The speed and scale of the current outbreak demonstrate how quickly animal diseases can spread through modern agricultural systems, potentially creating conditions for viruses to adapt to new hosts—including humans. The H5N1 virus, known as bird flu, is rapidly mutating in ways that are dangerous for famed animals, wildlife, and human health.

As consumers, understanding these connections helps us recognize that food prices reflect not just economic factors but also biological realities and public health considerations. The egg on your breakfast plate exists within a complex web of agricultural practices, disease ecology, and global health security. When prices rise dramatically, as they have for eggs, it often signals disruption within this system—disruption that may carry implications far beyond our grocery bills.

The current bird flu crisis serves as a reminder that our food systems remain vulnerable to biological threats, and that pandemic risks are not just historical concerns but ongoing challenges requiring vigilance, investment, and thoughtful approaches to agriculture and public health. As we navigate higher egg prices today, we would do well to consider how the lessons from this outbreak might help prevent more serious consequences tomorrow.

Looking Forward

While the immediate concern for most consumers is when egg prices might return to normal, the broader question involves how to build more resilient food systems that reduce pandemic risks while maintaining affordability and accessibility. Government investments in biosecurity, disease surveillance, and vaccine development represent important steps, but addressing the fundamental vulnerabilities in industrial animal agriculture may require more systemic changes.

For now, consumers can expect ongoing volatility in egg prices and occasional shortages, particularly for specialty eggs like cage-free and organic varieties. The situation serves as a vivid reminder that food security cannot be taken for granted, and that the health of our agricultural systems is inextricably linked to human health security. By understanding these connections, consumers can make more informed choices while advocating for food systems that prioritize not just efficiency and affordability, but also resilience and safety.

Latest fact-checks, guides & opinion pieces

.svg)