What do egg prices have to do with pandemics? Understanding the bird flu crisis

The price of eggs has skyrocketed in recent months, leaving many consumers shocked at checkout counters across America. This dramatic increase is not simply due to general inflation, but rather points to a much more concerning issue with potential global implications. The current egg shortage and price surge are directly linked to a widespread bird flu outbreak that has devastated poultry farms, and some experts worry this situation represents more than just an economic inconvenience—it could signal pandemic risks that echo historical disasters like the 1918 Influenza Pandemic. Understanding this connection helps consumers make sense of not only why their breakfast costs more, but also how our food systems are interconnected with public health security.

The Recent Egg Price Crisis

The numbers tell a startling story about what's happening to egg prices. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average cost of a dozen large, Grade A eggs has risen from $2.52 in January 2024 to a record-high $4.95 in January 2025. This represents a dramatic 53% increase in just one year, far outpacing overall food inflation, which rose just 2.5% during the same period. Despite a recent decrease in the price of wholesale eggs, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) projects that egg prices will continue to climb, potentially increasing by more than 40% throughout 2025. For the average family, this means eggs—once considered an affordable protein source—have become a significant budget consideration.

"While consumer choice is important, it's only one piece of the puzzle. We need to address the vulnerability of our food systems by advocating for federal regulatory action, improved tracking, and a systemic shift towards climate-resilient farming that prioritizes habitat protection and disease prevention, ultimately safeguarding us from future pandemics" - Dr Jennifer Molidor

This price surge stems directly from a widespread outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), commonly known as bird flu. The current strain, H5N1, has proven particularly devastating to poultry populations. In December 2024 alone, outbreaks resulted in the "depopulation" (a term used to describe the necessary culling of infected and exposed birds) of 13.2 million birds, according to USDA data. Since October, when the latest wave of outbreaks began, more than 52 million egg-laying hens have been affected across ten states, including Arizona, California, Indiana, Iowa, Missouri, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Utah, and Washington. To put this in perspective, these losses represent approximately 17% of the total U.S. egg-laying hen population in just four months. The fourth quarter of 2024 was particularly devastating, with more than 20 million egg-laying chickens lost to the virus—marking the worst toll on America's egg supply since the outbreak began.

How This Affects Your Shopping and Dining Experience

The effects of this crisis extend beyond just higher prices at the grocery store. Many retailers have implemented egg purchase limits to prevent stockpiling and ensure fair distribution. Major chains including Trader Joe's, Costco, and Sprout have restricted the number of egg cartons customers can buy. Shoppers in some regions have encountered completely empty egg shelves, particularly for cage-free and organic varieties, which have been disproportionately affected by the outbreak. Despite representing only about a third of U.S. egg layers, cage-free hens accounted for nearly 60% of all bird flu cases in 2024.

The impact extends to restaurants as well. In February, Waffle House—an American breakfast staple—announced a 50-cent surcharge for each egg ordered due to the shortage and price increases. "While we hope these price fluctuations will be short-lived we cannot predict how long this shortage will last," the chain stated in a press release. Many other restaurants have either raised prices, reduced egg-heavy menu options, or looked for alternatives to manage costs.

Government officials are implementing various measures to address the shortage. Nevada's Department of Agriculture temporarily suspended state laws requiring eggs to be cage-free and allowed the sale of Grade B quality eggs, which are typically used in processed food products rather than sold directly to consumers. In New York, Governor Kathy Hochul ordered the closure of live bird markets after the virus was detected in seven markets across New York City. These emergency measures highlight the severity of the situation.

Beyond Your Breakfast Plate: A Spreading Threat

The bird flu crisis extends far beyond just chickens and eggs. Since 2024, the H5N1 strain has spread to dairy cows, raising additional concerns about food security and public health. 17 states have now reported cows infected with H5N1, which kills around 2% to 5% of infected dairy cows and can reduce a herd's milk production by 10% to 20%. This expansion to mammals represents a concerning evolution of the virus, as each new species provides opportunities for the virus to mutate and potentially become more dangerous to humans, as well as to other wildlife and endangered species.

While it is reported that the health risk to most able-bodied people remains low at present, the situation requires careful monitoring, particularly for people living in vulnerable communities with inadequate testing and reporting. Several human cases of bird flu have already been reported, primarily among farm workers with direct exposure to infected animals. Public health experts note that the virus continues to "surprise" them with its ability to adapt and spread, emphasizing that the risk assessment "could change, and could change quickly". Food safety experts reassure consumers that properly cooked eggs and poultry remain safe to eat, as normal cooking temperatures (heating foods to at least 165 degrees) destroy the virus along with other common pathogens like Salmonella.

The current situation draws concerning parallels to historic pandemics. The most notable comparison is to the 1918 influenza flu pandemic, which represents one of the deadliest disease outbreaks in human history. Estimates of the death toll from that pandemic vary considerably. Early estimates from 1927 put the figure at 21.6 million deaths worldwide. More recent reassessments in 2018 estimated about 17 million deaths, though other studies suggest the number could be much higher—between 50 million and 100 million. In India alone, the 1918 influenza pandemic flu killed between 12 and 14 million people, making it the only census period (1911-1921) in which India's population decreased. The devastating impact of that pandemic serves as a sobering reminder of what can happen when novel influenza viruses spread unchecked through human populations.

The Economic Ripple Effects

The financial impact of the bird flu crisis extends throughout the food system. Since 2022, the USDA has invested more than $1.7 billion in combating bird flu on poultry farms, including reimbursing farmers who have had to cull their flocks. An additional $430 million has been spent addressing the spread to dairy farms. In February 2025, the Trump administration announced a new $1-billion plan aimed at fighting the virus and ultimately bringing down egg prices. Most of these funds are earmarked for providing relief to affected farmers and expanding biosecurity measures at egg-laying facilities, with about $100 million dedicated to vaccine research and exploring egg import options.

For farmers like Brian Kreher, a fourth-generation egg producer in New York, the outbreak has created existential challenges. "Egg farmers are in the fight of our lives and we are losing," he told the BBC in a February interview. Many farmers face impossible choices, such as whether to accept chicks from areas near virus hotspots, knowing the risks but also understanding that without new birds, their operations would slowly cease to exist.

The impact extends to food manufacturers that rely on eggs as ingredients. Companies producing everything from baked goods to mayonnaise face higher production costs, which inevitably get passed on to consumers. Some businesses are exploring alternatives, creating potential opportunities for plant-based egg substitutes. For example, sales of plant-based egg alternatives jumped significantly in January 2025 compared to the previous year, according to reports from companies in this space.

What This Means for Consumers

As consumers navigate this challenging situation, understanding the connection between bird flu, egg prices, and potential pandemic risks helps inform both shopping decisions and broader perspectives on food systems. In the short term, expect egg prices to remain high and possibly increase further until poultry producers can rebuild their flocks—a process hampered by the ongoing virus circulation. Regional variations in price and availability will continue, with states that mandate cage-free eggs likely experiencing more severe shortages and higher prices.

For those looking to manage food budgets during this crisis, consider exploring recipes that use egg alternatives, or cook food that doesn’t require eggs at all. Tofu, legumes, and other plant proteins can also serve as nutritious alternatives in many recipes.

Food safety policy remains paramount. While bird flu virus particles have been detected in some dairy products, such as raw milk and cheeses, the FDA has reassured consumers that the commercial milk supply remains safe, particularly when pasteurized. This highlights the importance of pasteurization—not only for preventing bird flu transmission but also for eliminating other harmful pathogens that can thrive in raw milk. As already fact-checked by Foodfacts.org, raw milk can harbor dangerous bacteria such as Salmonella, E. coli, and Listeria, which pose significant health risks, especially to children, pregnant women, and those with weakened immune systems. Similarly, properly cooking eggs and poultry eliminates any potential virus risk. Continuing to follow standard food safety practices—such as thoroughly cooking animal products, avoiding cross-contamination, and washing hands after handling raw ingredients—provides protection against not only bird flu but also a wide range of more common foodborne pathogens.

The Bigger Picture: Food Systems and Pandemic Risk

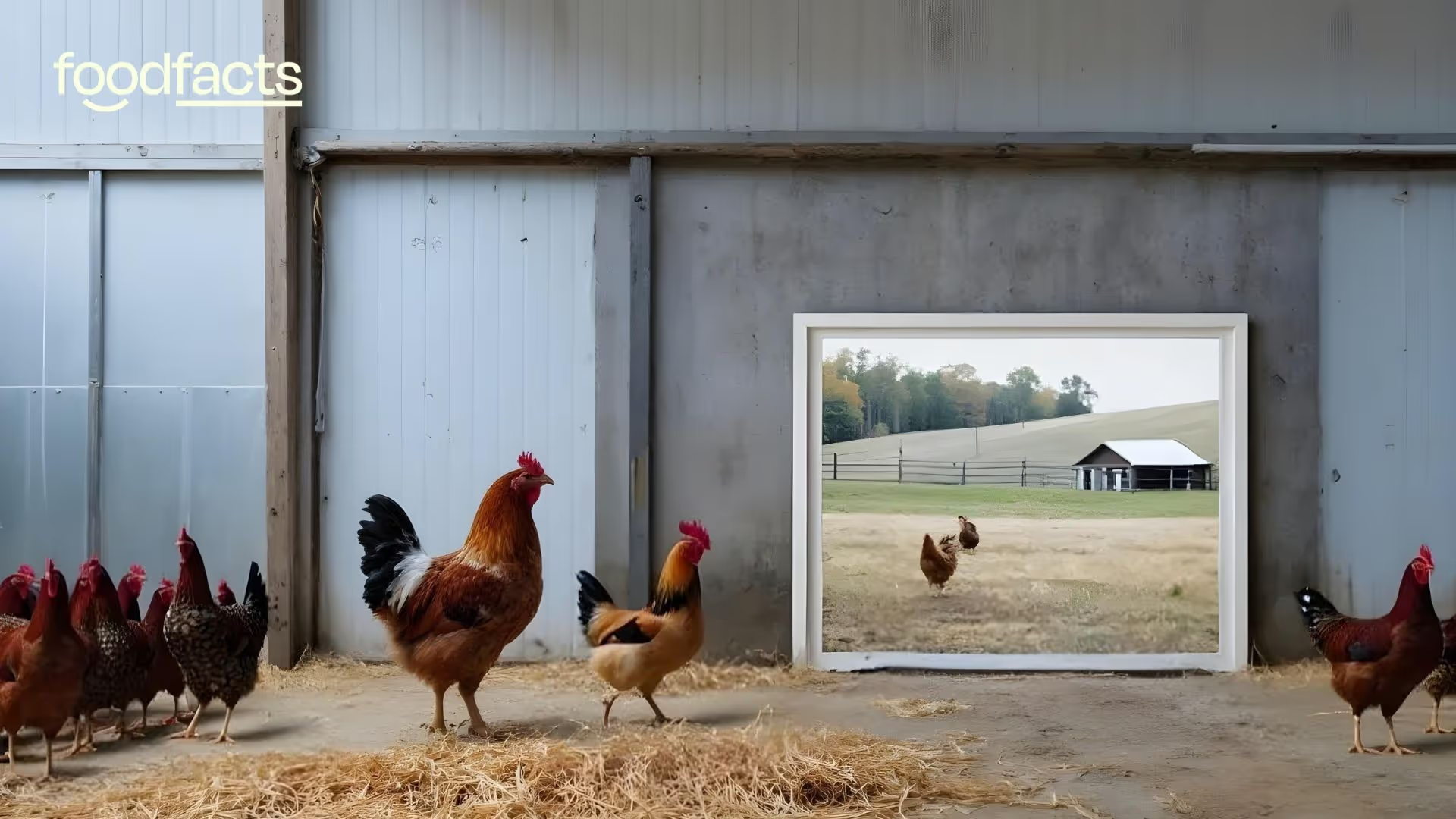

The current bird flu crisis illuminates the complex relationship between agricultural practices, food security, and public health. Intensive animal agriculture, while efficient at producing affordable protein, also creates conditions that can facilitate disease spread. High-density housing of birds, long-distance transportation of animals, and the genetic uniformity of commercial flocks all contribute to vulnerability when pathogens emerge.

Some experts suggest that improving animal welfare and hygiene conditions, reducing flock density, and shortening supply chains could help mitigate future outbreak risks. These approaches may increase production costs but could prove far less expensive than managing widespread disease outbreaks after they occur.

The ongoing situation also highlights the importance of robust pandemic monitoring and response systems. The speed and scale of the current outbreak demonstrate how quickly animal diseases can spread through modern agricultural systems, potentially creating conditions for viruses to adapt to new hosts—including humans. The H5N1 virus, known as bird flu, is rapidly mutating in ways that are dangerous for famed animals, wildlife, and human health.

As consumers, understanding these connections helps us recognize that food prices reflect not just economic factors but also biological realities and public health considerations. The egg on your breakfast plate exists within a complex web of agricultural practices, disease ecology, and global health security. When prices rise dramatically, as they have for eggs, it often signals disruption within this system—disruption that may carry implications far beyond our grocery bills.

The current bird flu crisis serves as a reminder that our food systems remain vulnerable to biological threats, and that pandemic risks are not just historical concerns but ongoing challenges requiring vigilance, investment, and thoughtful approaches to agriculture and public health. As we navigate higher egg prices today, we would do well to consider how the lessons from this outbreak might help prevent more serious consequences tomorrow.

Looking Forward

While the immediate concern for most consumers is when egg prices might return to normal, the broader question involves how to build more resilient food systems that reduce pandemic risks while maintaining affordability and accessibility. Government investments in biosecurity, disease surveillance, and vaccine development represent important steps, but addressing the fundamental vulnerabilities in industrial animal agriculture may require more systemic changes.

For now, consumers can expect ongoing volatility in egg prices and occasional shortages, particularly for specialty eggs like cage-free and organic varieties. The situation serves as a vivid reminder that food security cannot be taken for granted, and that the health of our agricultural systems is inextricably linked to human health security. By understanding these connections, consumers can make more informed choices while advocating for food systems that prioritize not just efficiency and affordability, but also resilience and safety.

The facts about protein: why science says more isn’t always better

Final Thoughts

This leads us to a significant issue posed by broad nutritional advice given on social media. This post by Jessie Inchauspé suggests that we should all eat more protein than we currently do, and think very carefully about protein intake, while data shows that the majority of people in countries like the UK or the US already meet protein requirements.

While Inchauspé suggests increasing protein intake through whole foods, this heightened focus on protein and fear of deficiency could lead people to unnecessarily turn towards protein supplements.

In reality, the focus should be on maintaining a well-balanced diet, which should provide everyone with the necessary amount of protein, but also with other essential nutrients to support overall health.

Other experts like Professor Tim Spector, Professor of Epidemiology at King’s College London, note that fears of protein deficiencies are generally unnecessary. Indeed he says that the real deficiency we suffer from in countries like the UK is that in fibre, which most people don’t consume enough of (source). Most high protein western diets are low in fibre and high in red meat and this leads to increased risk of Diverticulosis (inflammatory pouches in the colon).

This illustrates the importance of placing variety and balance at the forefront of nutrition discussions. Instead, social media narratives tend to use fear mongering techniques that get people to zoom onto one single issue (or non-issue) and forget the big picture.

Update and Clarification

We appreciate Jessie Inchauspé and her team's response to our request for clarification regarding the basis of the 2g protein recommendation. The studies provided highlight the importance of adequate protein intake for maintaining muscle mass and reducing the risk of certain chronic diseases. On the other hand, these studies also do not support the claim that all adults should aim for 2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily.

The first study referenced does not directly address protein intake, but rather medication used in diabetes treatment. Another study explores the association between muscle mass and mortality in older adults, emphasising the benefits of higher protein intake in this demographic but not advocating for a universal increase to 2 grams per kilogram.

Regarding the claim that many are "under-proteined," the evidence suggests that protein deficiency is more relevant to specific subpopulations, such as the elderly in long-term care facilities. In countries like the United States, data shows that most individuals already meet or exceed their protein requirements.

While these studies underscore the benefits of dietary protein, discussions about potential risks associated with high protein intake, particularly regarding kidney function, generally do not apply to healthy individuals. However, they do not support a broad recommendation to increase protein intake to 2 grams per kilogram for all adults.

Based on our research, including the studies provided by Inchauspé's team and data on protein consumption in Western countries, the evidence does not support a universal recommendation for all adults to aim for 2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Inchauspé’s post comes in the midst of a “protein hype,” which has led to a massive increase in sales of products boasting a high protein content. Registered Nutritionist Rhiannon Lambert recently addressed this issue in the podcast The Wellness Scoop:

“I think my job here just comes in to remind you that 1 to 1.2 grams per kilogram is kind of a rough ideal [...] For most people you don’t need to be overthinking it.”

Contrary to Inchauspé’s claim that we are all “under-proteined,” evidence shows that in industrialised countries, protein deficiency is rarely a concern. According to the British Dietetic Association, “In the UK, overconsumption of protein is common across all age groups and sexes” (source).

Is There Such a Thing as Too Much Protein?

Overly focusing on protein intake among people who follow a ‘regular lifestyle,’ in the sense that they follow the minimum recommendations for weekly exercise, could also lead people to supplementation and overconsumption.

Chronic high protein intake refers to consistently consuming more than 2g of protein per kg of body weight (so above what Inchauspé recommends we should all aim for). It can lead to digestive, renal, and vascular abnormalities and is therefore not generally recommended (source). In these quantities, “extra protein is not used efficiently by the body and may impose a metabolic burden on the bones, kidneys, and liver” (source).

Diets that are particularly high in protein tend to be associated with increased intake of saturated fats which can lead to negative outcomes (source), mainly relating to cardiovascular health.

What about longevity?

Inchauspé supports her claim by saying that protein is “the key to longevity.” However, according to Dr Amati, Inchauspé’s suggestion to disregard recommended protein amounts does not support long-term health.

For example, Inchauspé’s post could encourage people to consume more animal protein than they already do, in an effort to boost their daily protein intake. Indeed the examples listed for protein-rich meals here are: eggs, greek yoghurt, salmon and chicken.

On the other hand, studies have pointed to the role of increased plant protein intake to support long-term health outcomes. In this meta-analysis of 31 studies, researchers concluded that replacing foods high in animal protein with plant protein could have positive effects on longevity.

Article updated on March 24, 2025 to reflect response from the Glucose Goddess' team. See final paragraph for further details.

The current recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for protein is 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight per day.

Protein needs can vary at different stages of our life. Various factors such as pregnancy, being elderly, illnesses or long-term conditions can all increase protein requirements (source). For example, elderly people can get sarcopenia (decline in muscle mass) from low protein diets.

Inchauspé suggests that everyone should aim for about 2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily to "thrive and build muscle mass." There are certain groups of people who would benefit from increasing their protein intake, such as strength athletes or older people. Even then, recommendations generally fall between 1-1.2 and 1.6g per kg of body weight. We contacted Jessie Inchauspé’s team to ask for clarification regarding the basis of this 2g recommendation. In their response, her team specified that “1.6 to 2g per kg of bodyweight was ideal for athletes or older adults to prevent muscle loss.”

According to Dr Federica Amati, Nutrition Lead at Imperial College London’s School of Medicine, 2 grams per kilogram of body weight goes above even what is recommended for improving strength and body composition, so suggesting that this is what everyone should aim for is not appropriate.

So what about the general population? Dr Federica Amati breaks down Inchauspé’s claims against the available evidence on protein intake and health outcomes across various populations:

The recommended amount is calculated to provide more than what 97.5% of the adult population (18-65) need to maintain healthy muscle mass (the minimum is actually 0.71 g/kg). It is not a recommended minimum intake, it is the recommended intake.

Most adults get 1-1.2g/kg from food alone and 70-80% of that comes from animal protein. We don’t need to be encouraging MORE animal protein consumption to benefit public health.

1.6g/kg of ideal body weight, an important distinction to make whenever talking about protein, is for sure a higher recommended amount for people engaging in progressive load strength training - not those who get the bare minimum of 150 minutes of exercise per week.

Older adults also need to increase their protein to retain healthy muscle mass, but movement is key here too and it increases to about 1-1.2g/kg.

To echo Rhiannon Lambert’s words on this topic, people don’t eat grams of protein, they eat foods. Focusing on a variety of plant and animal protein, with more education around plant proteins, is what we need to focus on to improve public health.

Cross-check facts: Compare the information with multiple trusted sources to confirm accuracy.

Jessie Inchauspé, known as the Glucose Goddess, recently claimed that the current recommended daily protein intake of 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight is “a joke” and that people should aim for about 2 grams per kilogram to thrive. Conflicting advice on protein intake is rife on social media. Amid growing confusion, it is easy to start overthinking every meal. We bring you a reality check so you can make informed decisions about what is right for you.

While higher protein intake is beneficial for muscle gain and strength, especially for athletes or those engaging in regular strength training, experts’ recommendation for most adults tends to fall between 1 and 1.2 grams per kilogram per day. Inchauspé's suggestion is more aligned with the needs of specific groups like strength athletes rather than the general population.

Social media is full of one-size-fits-all solutions promising to enhance well-being or even cure ailments. These simplistic answers often overlook the complexity of individual health needs, which in some cases can lead to potential harm.

The high-protein, gut-friendly food that's been a staple for centuries. And it's going mainstream

Tempeh, a traditional Indonesian fermented food, has been quietly nourishing communities for centuries with its impressive nutritional profile and distinctive nutty flavor. Today, this ancient protein source is experiencing a remarkable surge in popularity as health-conscious consumers worldwide discover its numerous benefits. This compact cake of fermented soybeans delivers a complete protein profile while offering gut-friendly probiotics, essential vitamins, and minerals that support overall wellbeing. As plant-based eating continues to gain momentum globally, tempeh stands out as an exceptionally versatile ingredient that satisfies discerning palates while providing substantial nutritional value without the environmental footprint of animal products.

The Ancient Origins of Tempeh

Tempeh's rich history dates back centuries to the island of Java in Indonesia. According to historical evidence, tempeh was first documented in Bayat, Klaten, Central Java, in the 1600s. The fascinating origin story suggests that tempeh was discovered serendipitously when cooked soybeans wrapped in tree leaves were left to ferment in Indonesia's warm, humid climate. What began as a chance discovery soon became an integral part of Indonesian cuisine and culture, spreading throughout the region.

The invention of tempeh likely occurred through the chance introduction of the Rhizopus fungus to stored soybeans. This fungus naturally grows on teakwood and sea hibiscus leaves, which Javanese people traditionally used as food wrappings. In traditional tempeh making, an "usar" (a mycelium-grown leaf) was used instead of commercially produced starter cultures that are common today. The earliest documented evidence of tempeh appears in Serat Centhini, a book published in the 16th century, indicating that tempeh production and consumption were already established practices by that time.

Initially, black soybeans native to the region were used to make tempeh. This practice later changed with the importation of white or yellow soybeans and the growth of the tofu industry on the island. The first European reference to tempeh appeared in 1875 in a Javanese-Dutch dictionary, marking the beginning of tempeh's introduction to the Western world. The traditional production methods evolved over time, with plastic bags eventually replacing banana leaves as containers for tempeh production in the 1970s. This innovation helped standardize the fermentation process and facilitated commercial production, setting the stage for tempeh's global journey that continues to accelerate today.

What Exactly is Tempeh?

Tempeh is a compact cake made from soybeans that have been cooked and then fermented with a specific culture, resulting in a firm, cake-like product with a distinctive nutty flavor. The production process involves soaking soybeans overnight, cooking them for approximately 30 minutes, and then mixing them with a tempeh starter culture, typically Rhizopus oligosporus, a fungus of the family Mucoraceae. During the fermentation period of 36 to 48 hours, the Rhizopus mold grows throughout the soybeans, binding them together and creating the characteristic solid texture that sets tempeh apart from other soy products.

Unlike tofu, which is made from soy milk and has a softer texture, tempeh retains the whole soybean and has a firmer, meatier bite that many find more satisfying. The textural difference makes tempeh particularly appealing as a meat substitute in various dishes. As Cleveland Clinic dietitian Gillian Culbertson explains, "With tempeh, I would almost describe it as having a meatier texture to it. It has more of a bite to it, whereas tofu is usually softer". The fermentation process also gives tempeh a more complex flavor profile compared to tofu, with notes often described as nutty or mushroom-like.

Though traditionally made with soybeans, tempeh can also be produced using other legumes, grains, and even seeds. Modern variations include multigrain tempeh (incorporating rice, wheat, or barley) and innovative varieties made from black-eyed beans, chickpeas, or other legumes. These alternatives offer different nutritional profiles and flavor experiences, expanding tempeh's versatility in the culinary world. The fermentation process not only enhances the food's digestibility but also increases its nutritional value by breaking down compounds that might otherwise inhibit nutrient absorption.

Nutritional Powerhouse: Breaking Down Tempeh's Benefits

Tempeh stands out as an exceptional nutritional powerhouse, particularly for those seeking plant-based protein sources. On average, a 100g serving of tempeh provides approximately 166 calories, a substantial 20.7g of protein, 6.4g of fat, 6.4g of carbohydrates, and an impressive 5.7g of fiber. This protein content makes tempeh especially valuable for vegetarians and vegans, as it contains all nine essential amino acids that the human body cannot produce on its own, qualifying it as a complete protein. The protein density of tempeh surpasses many other plant-based options, making it an efficient way to meet daily requirements.

The compactness of tempeh gives it a nutritional edge over other soy products. While 3 ounces (84 grams) of tempeh delivers about 15 grams of protein, the same amount of tofu contains only about 6 grams, representing a significant difference of approximately 40%. Beyond protein, tempeh provides substantial amounts of essential minerals including calcium (120mg per 100g), iron (3.6mg per 100g), and magnesium (70mg per 100g). These minerals play crucial roles in bone health, oxygen transport, and numerous enzymatic reactions in the body.

Tempeh is also remarkably rich in B vitamins, with a 3-ounce serving providing approximately 18% of the recommended daily intake of riboflavin and 12% of niacin. Additionally, tempeh can contain vitamin B12, which is relatively rare in plant foods and particularly valuable for those following plant-based diets who might otherwise struggle to meet their B12 requirements. The manganese content is especially notable, with a single serving providing 54% of the recommended daily intake. This trace mineral plays important roles in metabolism, bone formation, and antioxidant functions.

The fermentation process that creates tempeh brings additional nutritional benefits by breaking down anti-nutrients that might otherwise inhibit mineral absorption. This process essentially pre-digests some components of the soybeans, making tempeh easier to digest and its nutrients more bioavailable than those in unfermented soy products. For those monitoring their sodium intake, tempeh is naturally very low in sodium, containing only about 9 milligrams per 3-ounce serving, making it a heart-healthy protein option that can be seasoned according to individual preferences and dietary needs.

Health Benefits That Make Tempeh a Superfood

The health benefits of tempeh extend far beyond its impressive nutritional profile, making it a true superfood with multiple advantages for various aspects of health. The fermentation process creates prebiotic fiber, which feeds beneficial bacteria in the gut, helping them thrive and multiply. Though tempeh is cooked before consumption and some commercial varieties are pasteurized (potentially reducing live probiotic content), it remains rich in the type of fiber known to be prebiotic. The gut bacteria nourished by this fiber produce short-chain fatty acids that have beneficial effects not only on gut health but also on overall wellbeing.

Tempeh's high protein content makes it particularly effective for weight management. Protein has a well-documented satiating effect, which helps control appetite and potentially reduce overall calorie intake. The combination of protein and fiber in tempeh creates a feeling of fullness that typically lasts longer than many other foods, making it a valuable addition to a weight-conscious diet without sacrificing nutritional quality or satisfaction. For those looking to manage their weight while maintaining muscle mass, tempeh provides an excellent solution.

The soy isoflavones present in tempeh are powerful plant compounds with protective antioxidant properties that may help minimize damage caused by oxidative stress in the body. These phytoestrogens offer particular benefits for women's health, especially during and after menopause. Studies suggest that including soy foods like tempeh in the diet may contribute to reducing hot flashes and supporting bone health in post-menopausal women through improvements in bone metabolism. The compounds mimic some of estrogen's effects in the body, potentially helping to ease the transition through hormonal changes.

For cardiovascular health, tempeh offers multiple benefits that may contribute to a healthier heart. Research suggests that regular consumption of tempeh may help manage cholesterol levels, potentially reducing the risk of heart disease. The combination of fiber, unsaturated fats, and soy isoflavones contributes to this heart-friendly profile, making tempeh an excellent replacement for less healthy protein sources in the diet. The low sodium content of unflavored tempeh further enhances its cardiovascular benefits.

Recent research has also highlighted tempeh's potential role in athletic performance and recovery. The paraprobiotic properties of fermented foods like tempeh may help restore from fatigue and reduce anxiety in athletes. This is achieved through increased protein synthesis activity in pathways involved in the integrated stress response. Additionally, these paraprobiotics may help maintain mitochondrial function and support recovery from fatigue by preventing certain types of gene down-regulation associated with oxidative phosphorylation. For active individuals, incorporating tempeh into pre- or post-workout meals could potentially enhance performance and recovery.

How Tempeh is Going Mainstream In Western Markets

The rising popularity of plant-based diets has propelled tempeh from a niche vegetarian staple to a mainstream food product available in an increasing number of supermarkets and health food stores. No longer confined to specialty Asian grocery stores, tempeh can now be found in various forms across retail outlets, making it more accessible than ever before to curious consumers and those seeking sustainable protein alternatives.

The spread of tempeh from Indonesia to the UK, Europe, and the US was catalysed by migrations of Indonesians and collaborative research activities on tempeh fermentation. For example, some of the first scientific publications on tempeh fermentation in Dutch coincided with the Dutch colonialism in Indonesia (Ahnan-Winarno et al., 2021). Home fermentation movements and demands for plant-based proteins are thought to trigger larger tempeh productions that lead us to the current tempeh industries in those countries.

Commercially, there are a number of succesful brands, a stand out examples of tempeh's rise in popularity in the UK is Better Nature. Launched in 2020, this innovative brand has made significant strides in bringing tempeh to mainstream audiences. Their mission is to make wholefood proteins the norm, not the alternative, and they’ve done just that by securing listings in major retailers such as Tesco, Asda, Lidl, Ocado, Planet Organic, and Whole Foods Market. Better Nature has also become a best-seller on Amazon UK and has expanded into food service through partnerships with distributors like Bidfood, as well as entering the German market with leading retailers like Rewe and Tegut.

What makes Better Nature stand out is not just their rapid growth but their commitment to sustainability and community impact. As a certified B Corp™, they put people and the planet ahead of profit, donating 1% of their sales to tackle malnutrition in Indonesia, the birthplace of tempeh. Using sustainably grown, non-GMO soybeans, they ensure their tempeh has a low carbon footprint, verified by farm-to-fork analysis from My Emissions. Better Nature's success story highlights how tempeh is no longer a niche product but a dynamic and rapidly growing staple in the UK’s plant-based food scene.

How to Cook Tempeh: Simple Techniques for Delicious Results

One of tempeh's greatest attributes is its culinary versatility, which allows it to be prepared in numerous ways while maintaining its structural integrity and nutritional benefits. For those new to cooking with tempeh, understanding a few basic preparation techniques can help achieve delicious results consistently and build confidence in working with this nutritious ingredient.

A recommended first step when cooking tempeh is steaming, which helps soften the texture and allows it to absorb flavors more effectively. This process involves cutting the tempeh into your desired shape (cubes, slices, or triangles), placing it in a steamer basket over simmering water, covering, and steaming for approximately 10 minutes. While this additional step might seem unnecessary, it could improve the final dish by reducing any potential bitterness and enhancing tempeh's ability to absorb marinades. The brief steaming period opens up the dense structure of the tempeh, allowing flavors to penetrate more deeply.

Marinating tempeh is another key technique for developing flavor. An effective basic marinade might combine tamari or soy sauce (¼ cup), rice vinegar (2 tablespoons), maple syrup (2 tablespoons), olive oil (1 tablespoon), and sriracha (1 teaspoon) for a balance of salty, sweet, sour, and spicy notes. Even a brief 30-minute marination can infuse tempeh with considerable flavor, though longer marination times generally produce more flavorful results thanks to tempeh’s sponge-like mycelium formed during fermentation. The dense structure of tempeh allows it to hold up well during marination without becoming mushy, unlike some other protein alternatives.

Baking marinated tempeh offers perhaps the most straightforward cooking method and works well for beginners. After marinating, arrange the tempeh pieces on a parchment-lined baking sheet and bake at approximately 425°F (220°C) for about 20 minutes, turning halfway through and brushing with additional marinade for extra flavor development. The high heat creates a slightly crisp exterior while maintaining a tender interior, creating a pleasing textural contrast and caramelizing the sugars in the marinade for enhanced flavor.

For those who enjoy grilled foods, tempeh holds up exceptionally well on the grill. This method works best with larger pieces, such as triangular "steaks" or thick slices. After marinating, grill the tempeh over medium heat for 7-9 minutes until char marks form, then brush with more marinade, flip, and grill for another 4-5 minutes. The smoky flavor from grilling complements tempeh's natural nuttiness beautifully, creating a satisfying meat-like experience that even dedicated omnivores can appreciate.

In Indonesia, a common and beloved preparation involves slicing or dicing tempeh and frying until the surface is crisp and golden brown. This method highlights tempeh's ability to develop different textures based on cooking techniques. The crispy exterior and tender interior create a delightful contrast that makes fried tempeh pieces perfect for adding to salads, grain bowls, or enjoying as a protein-rich snack with dipping sauces. For a healthier alternative, air-frying can produce similar results with significantly less oil.

Incorporating Tempeh Into Your Daily Diet

Integrating tempeh into your regular meal rotation can transform your nutritional intake while expanding your culinary horizons. The beauty of tempeh lies in its adaptability—it works wonderfully as both a center-of-plate protein and as a complementary ingredient in complex dishes. For those new to tempeh, starting with familiar preparations can ease the transition and build appreciation for this nutritious food.

Breakfast offers an excellent opportunity to incorporate tempeh into your day. Crumbled and seasoned tempeh can serve as a nutritious alternative to breakfast meats alongside eggs or plant-based alternatives. Marinated tempeh slices can be pan-fried until crisp for a bacon-like addition to the morning meal, providing a protein-rich start to the day without processed meats. Tempeh also works beautifully in breakfast burritos, where its firm texture holds up well amidst other ingredients.

For lunch and dinner applications, tempeh shines in numerous roles across diverse culinary traditions. Cubed tempeh absorbs the flavors of curries, stews, and stir-fries while maintaining its structural integrity, unlike many other plant proteins that might break apart during cooking. This quality makes it particularly valuable in dishes with robust sauces where you want the protein component to remain distinct. The firm texture also makes tempeh an excellent candidate for skewers or kebabs, holding together beautifully on the grill.

Sandwiches and wraps benefit tremendously from marinated and grilled tempeh slices, which provide substantial protein and satisfying texture. A tempeh Reuben with sauerkraut and Russian dressing or a tempeh BLT showcases how effectively tempeh can step into traditionally meat-centric roles. The firm texture ensures that tempeh doesn't compress or become soggy in sandwiches, maintaining a satisfying bite throughout your meal.

For those interested in exploring tempeh's Indonesian roots, dishes like tempeh goreng (fried tempeh), tempeh mendoan (tempeh fritters), or sambal goreng tempeh (spicy tempeh in coconut milk) offer authentic ways to enjoy this traditional food. These preparations showcase tempeh's ability to absorb rich, complex flavors while maintaining its distinctive character. Even simple preparations, like tempeh sautéed with soy sauce and garlic, allow its natural nuttiness to shine.

Adventurous home cooks might consider making tempeh from scratch, a process that, while requiring patience, is relatively straightforward. Homemade tempeh often tastes better than store-bought varieties and can be significantly more economical, costing approximately one-fourth of the price of commercial tempeh. The process involves soaking soybeans overnight, cooking them for about 30 minutes, mixing with tempeh starter, and then fermenting for 36-48 hours. The resulting fresh tempeh offers an unparalleled flavor and texture experience that deepens appreciation for this remarkable food.

The Future of Tempeh: Sustainability and Global Potential

As concerns about the environmental impact of food production intensify, tempeh stands out as a sustainable protein option with significant potential to address multiple challenges. The production of tempeh requires significantly fewer resources than animal-based proteins, making it an environmentally responsible choice for conscious consumers. Soybeans, the primary ingredient in traditional tempeh, fix nitrogen in the soil, potentially reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers when grown in sustainable rotation systems.

The fermentation process that creates tempeh represents an ancient form of food preservation that remains relevant in addressing modern food security challenges. By transforming relatively inexpensive ingredients into nutritionally dense food with an extended shelf life, tempeh production offers solutions to both nutritional adequacy and food waste concerns. The relatively simple production process also makes tempeh an accessible protein option for diverse economic contexts around the world.

The versatility of tempeh extends beyond culinary applications to include adaptability in production methods and ingredients. While traditional tempeh relies on soybeans, innovative producers are creating tempeh from various legumes, grains, and seeds, offering alternatives for those with soy allergies or concerns. This adaptability ensures that tempeh can be produced using locally available ingredients across different geographical regions, potentially reducing transportation emissions and supporting local agricultural systems.

As tempeh continues its journey from traditional Indonesian kitchens to global markets, its future appears bright. The convergence of health consciousness, environmental awareness, and culinary exploration creates an ideal environment for tempeh to flourish. With ongoing research revealing additional health benefits and creative chefs developing new preparation methods, tempeh's trajectory seems poised for continued growth and innovation in the coming years.

For those yet to experience tempeh, now is the perfect time to explore this remarkable food that bridges ancient wisdom and contemporary nutritional science. Whether you're seeking a sustainable protein source, a gut-friendly fermented food, or simply a delicious new ingredient to expand your culinary repertoire, tempeh offers a solution with centuries of tradition behind it and a promising future ahead. As this Indonesian staple continues to go mainstream globally, it carries with it not just nutritional benefits but also cultural heritage and sustainable food practices that enrich our collective food experience.

What is collagen and should you be supplementing it?

What is collagen?

Collagen supplementation has been floating around social media, with influencers promoting various collagen products and supplements, but what is collagen even?

Collagen is the most common protein in the body, and is found in all kinds of connective tissue, including skin, joints, cartilage, muscles, and bones. It’s what makes these tissues stretchy and able to withstand the demands of our daily lives.

So far, 28 types of collagen have been identified in the human body, but types I, II, and III, are the most common, with type I and III most commonly found in skin.

Our bodies produce their own collagen, but production naturally slows down as we age, typically thought to peak around age 25 and then slowly declining. Decline of natural collagen levels is one of the reasons skin starts to get less stretchy as we age and may start to sag or form deeper wrinkles.

What are the skincare claims related to collagen?

Many collagen supplements claim to contribute to healthier, more youthful looking skin, thicker hair, and stronger nails, by replenishing the collagen that is lost from our bodies with time. Is collagen the fountain of youth people have spent centuries searching for?

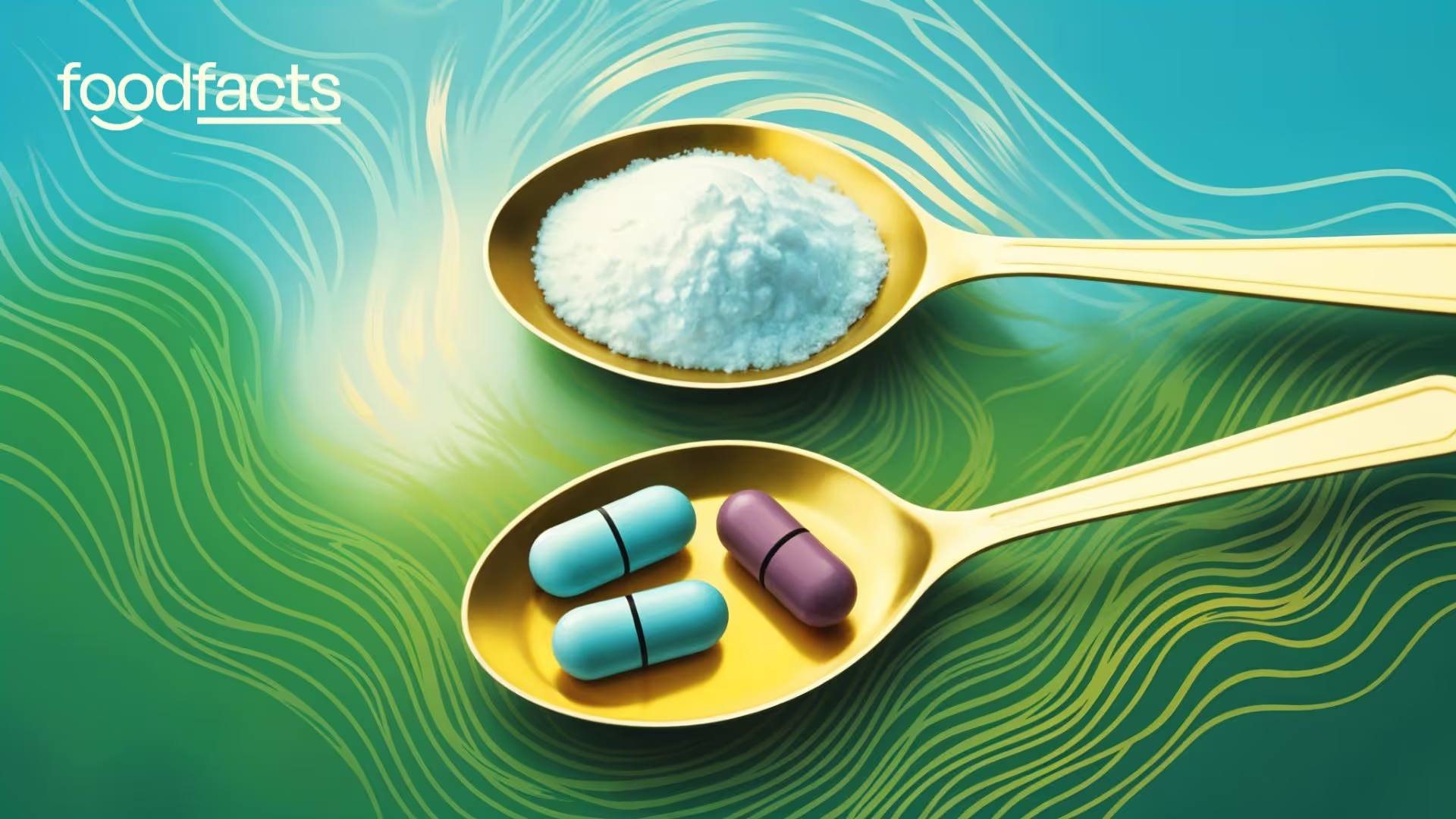

How can collagen be supplemented?

Collagen can be supplemented in a variety of ways. The most common form is oral supplementation through collagen powders, capsules, or gummies.

Most collagen supplements contain either bovine (from cows) or marine (from fish) collagen. Some foods, for example bone broth, also naturally contain gelatine. Powder supplements are almost always in the form of hydrolysed collagen, where the large collagen molecules have been broken down into smaller parts called peptides, which makes them dissolvable in water and easier for the body to absorb.

Marine collagen is extracted from a variety of marine animals, including fish by-products, such as scales, head, and bones, from the food sector. The most common kind of collagen found in fish is type I, although some type II collagen is also present, suggesting it may be beneficial for both skin and cartilage health.

Bovine collagen, on the other hand, comes mostly from cows, although the bovine species also includes yak, antelope and bison, among others. Other than marine collagen, bovine collagen contains mainly types I and III collagen, which are the main types of collagen found in skin.

Marine sources of collagen have been found to be easier for the body to absorb and have lower risk of causing inflammation, compared with bovine collagen.

For those following a plant-based diet, there are a range of vegan collagen supplements. Science has come a long way, and true vegan collagen can be made with genetically modified yeast or bacteria that are manipulated to produce the amino acids (protein building blocks) that make up collagen, before adding an enzyme that rearranges the amino acids into the same structure as human collagen- pretty cool! However, most vegan collagen supplements (or ‘boosters’, as they’re often called), don’t contain this form of collagen, but rather opt for a more accessible blend of amino acids that make up collagen, as well as some other micronutrients that have been linked to collagen synthesis in the body, like Vitamin C.

What do clinical studies say about these benefits?

With the collagen supplement market being valued at almost $10 billion in 2024, it begs the question- does science back up the claimed benefits of supplementing collagen or is it not much more than a marketing gimmick?

In general, various studies and meta-analyses have found improved skin elasticity and hydration following supplementation with hydrolysed collagen, but even scientists hesitate to make definitive statements. For one, some studies were done on mice, and the results may not be transferable to humans. Secondly, even in human studies, sample sizes are often small, which limits the strength of the conclusion, and the results were often self-reported, ie. subjects would report whether they felt like their skin seemed more elastic or hydrated after taking a supplement (or placebo) for a while, which can be difficult to confirm with more objective measures.

Some studies that show a benefit also use a combination of active ingredients, such as this one that tests a blend including collagen, biotin, vitamin C and E, so results might differ if collagen alone is supplemented.

Collagen can also be added to skincare like creams and serums, however, since collagen fibres are too large to penetrate the outer layers of the skin, they remain on the surface and do not affect skin quality.

Are there any other benefits of collagen?

Aside from potential benefits for skin health, studies have also suggested that collagen supplementation may have a positive impact on athletes experiencing joint pain, improve symptoms in patients with osteoarthritis, and may even increase heart health. Just like the skin health related trials discussed above, it is important to remember that these studies are not conclusive and only show a link, but don’t prove causation without any further research.

Final Take

The science around collagen supplements is not yet conclusive, and the global supplement market is valued at almost half a trillion USD, so supplement companies stand to benefit from consumers feeling pressured to add various supplements to their diet.

Collagen supplementation can be tentatively linked to various health benefits, but, as always, it is important to remember that there is no quick fix for (skin) health, and a balanced diet and lifestyle should be a priority.

Yes, folic acid is synthetic, but that doesn’t mean it’s harming your child’s behaviour

Understanding Folate and Folic Acid: The Basics

Before addressing specific claims, it's important to understand what folate and folic acid actually are. Both are forms of vitamin B9, which is essential for numerous bodily functions including the production of DNA, red blood cell formation, and cellular growth.

What is Folate?

Folate is a water-soluble B vitamin naturally found in many foods including spinach, kale, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, broccoli, oranges, nuts and seeds, and some animal products like liver. The term "folate" serves as an umbrella term for all forms of vitamin B9, including naturally occurring folates and synthetic folic acid.

What is Folic Acid?

Folic acid is the synthetic form of folate discovered in the 1940s. It's commonly added to fortified foods and used in dietary supplements because it remains intact during food processing and cooking, unlike natural folates, which can be destroyed during food storage and preparation. Our ability to get enough folate using folate from food alone is limited because of its instability during cooking.

Claim 1: "Folic acid is an entirely man-made nutrient. We've been told that it's vitamin B9, it's not."

Fact check: Partially true but misleading.

Folic acid is indeed a synthetic (man-made) form of vitamin B9, but the claim that "it's not vitamin B9" is incorrect. The scientific literature clearly establishes that folic acid is a synthetic version of folate, and both are forms of vitamin B9.

Folate refers to the many forms of vitamin B9, including folic acid, dihydrofolate (DHF), tetrahydrofolate (THF), and other derivatives. They all ultimately serve the same functions in the body, though they are processed slightly differently by the body.

Claim 2: "Folate occurs naturally in nature. Folic acid does not occur anywhere on the surface of the earth."

Fact check: True.

This claim is accurate. Folate occurs naturally in many foods, while folic acid is a synthetic compound created in laboratories. Food manufacturers fortify products like bread, cereals, pasta, and rice with folic acid, not the folate found in foods such as green leafy vegetables.

Claim 3: "About 44% of the population has a gene mutation that doesn't allow us to process [folic acid]."

Fact check: Inaccurate and Misleading.

A gene mutation is a small change in DNA that can affect how the body makes proteins. In this case, the MTHFR gene helps produce an enzyme needed to process folic acid. Some people have a common variant of this gene, which makes some of the enzymes work less efficiently, but it doesn’t mean they can’t process folic acid.

Here’s what the research actually shows:

- Around 25% of the global population has at least one copy of this variant. It's more common in Hispanic (47%) and European (36%) populations than in African (9%) populations.

- People with one copy of the mutation still retain about 65% of normal enzyme function.

- People with two copies of the mutation have about 30% of normal function, meaning they can still process folic acid, just less efficiently.

- Evidence shows that folic acid supplementation can be still effective in people with these mutations.

So while the 44% figure isn't entirely off for some populations, the claim that this mutation prevents folic acid processing altogether is incorrect. It just reduces efficiency, which may be relevant for certain health conditions but doesn’t mean folic acid is useless for those with the mutation.

Claim 4: “Remember, [grains, cereals, breads, pastas] contain folic acid and they could be sabotaging your health.”

Fact check: Unsupported by scientific evidence.

This claim suggests that eating foods fortified with folic acid is harmful, but research does not back this up.

Folic acid is absorbed more efficiently than natural folate. This means that consuming large amounts of folic acid can lead to some unmetabolised folic acid in the bloodstream.

Some studies have suggested possible links between high unmetabolized folic acid levels and adverse health outcomes such as colorectal cancer. However, experts caution that there is no clear evidence that unmetabolised folic acid causes harm, and other studies contradict these concerns. According to published research, “there are no definitive studies that have found health effects from exposure to unmetabolized folic acid”.

The benefits of folic acid fortification are clear. In the US, pregnancies with neural tube defects have fallen by 23% since fortification began in 1998. The public health benefits of folic acid far outweigh the theoretical risks for most people.

Claim 5: "Try eating a folic acid-free diet for one week and see the behavioural changes in your children."

Fact check: Unsupported by scientific evidence.

There is no substantial scientific evidence supporting the claim that removing folic acid from children's diets for one week will result in noticeable changes in behaviour.

This advice is concerning, given there is overwhelming evidence that folate (in all its forms) is crucial for proper brain function, healthy cell growth and DNA formation, and red blood cell production. There is also convincing evidence that later in life folic acid may play a role in the prevention of stroke and heart disease. Folic acid fortification has been implemented as a public health measure in many countries because it has proven benefits, particularly in reducing neural tube defects in developing fetuses, and it’s been shown that countries with mandatory folic acid fortification have reduced the number of neural tube defects among children. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that women capable of becoming pregnant consume 400 micrograms of folic acid daily to prevent birth defects.

In fact, research shows that when mothers get enough folic acid during pregnancy, it helps support their baby's brain development and childhood behavioural development.

The Debate Over Folate

Some health professionals and scientists argue that we should recommend a different form of folate called 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF or methyl folate) instead of folic acid. This is because, theoretically, this form bypasses the less efficient steps involving the mutated enzyme and is more bioavailable than folic acid.

However, it's important to note that folic acid is the only form extensively tested and proven to reduce neural tube defects. Even people with MTHFR mutations can still process folic acid, just less efficiently. Plus, major health organizations still recommend folic acid supplementation for all women of childbearing age, regardless of MTHFR status.

Conclusion

While folic acid is indeed synthetic and not naturally occurring, it is still a form of vitamin B9. MTHFR gene variants that affect folic acid metabolism are common, but having such variants doesn't mean someone cannot process folic acid at all. Most importantly, there's no scientific evidence supporting the claim that removing folic acid from children's diets for a week will improve their behaviour.

Decisions about dietary supplements should be made in consultation with healthcare providers based on individual health needs, rather than on generalized claims that lack scientific support.

This argument against folic acid is a textbook example of the ‘appeal to nature’ fallacy — the idea that something natural (like folate from food) is inherently better or safer than something synthetic (like folic acid). But folic acid is actually more stable and better absorbed by the body, which is why it’s used in supplements and food fortification to help prevent neural tube defects.

Be sceptical of bold claims that go against well-established science. Does the author share any robust evidence to support what they’re saying?

In a recent social media post, Gary Brecka suggests that folic acid is an entirely synthetic substance that 44% of people cannot process due to a gene mutation. He claims it could be ‘sabotaging your health’ and suggests that removing it from children's diets for one week could change their behaviour. In this article we investigate the accuracy of these statements to help you make informed decisions about folate and folic acid in your diet.

Gene variants that affect folic acid metabolism are common, but having such variants doesn't mean someone cannot process folic acid at all. Most importantly, there's no scientific evidence supporting the claim that removing folic acid from children's diets for a week will improve their behaviour.

The push to remove anything that is ‘synthetic’ from our diets may cause serious harm, as many of us rely on these ‘synthetically’ fortified foods to obtain enough of the essential nutrients.

The great fat debate: what science really says about butter and plant oils

A recent study published in JAMA Internal Medicine has sparked significant media attention by suggesting that replacing butter with plant-based oils may reduce the risk of premature death. Headlines have since labelled butter as a "deadly delight," while social media users have rejected its findings, calling it “junk science.” Here, we cut through the noise and conflicting advice from different media sources to review the relevance of this new study to your health.

The study

The study involved over 221,000 adults from three large American cohorts who were followed for up to 33 years. Researchers measured their intake of butter and plant-based oil over this period and the subsequent risk of dying from cardiovascular disease and cancer or premature death from any cause.

It's important to note that the study referenced in this article, published by JAMA Internal Medicine, specifically focused on a select group of vegetable oils, including olive oil, canola oil, and soybean oil. While these oils were associated with reduced mortality and cancer risk, the study did not comprehensively cover all seed oils, such as sunflower oil or others that some criticis have suggested are inflammatory, read our fact-check on seed oils and inflammation. Our intention is to reflect the findings of this particular study rather than make broad generalizations about all seed oils.

The results

Higher butter consumption was associated with a 15% increased risk of total mortality compared to the lowest intake. In contrast, a higher intake of plant-based oils, including safflower, soybean, corn, canola, and olive oil, was linked to a 16% lower risk of total mortality.

Moreover, the results suggest that swapping 10 grams of butter daily with plant-based oils could lower the risk of dying from any cause by 17% and cancer by 17%.

The results are likely explained, in part, by the different types of fatty acids found in butter and plant oils. Butter contains high amounts of saturated fatty acids, which can contribute to higher cholesterol levels, hardening of the arteries, and increased cardiovascular risk (source). The authors explain that the high saturated fat content in butter can also contribute to inflammation in fat tissue and alter hormonal activity, both of which can contribute to the development of various cancers.

On the contrary, plant-based oils are rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids, which have significant heart health benefits, including lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and reducing inflammation (source). They also have a higher antioxidant content than butter, particularly vitamin E, which may protect against oxidative stress and diseases such as cardiovascular disease (source).

Significant associations were seen between canola, soybean, and olive oils and a reduced risk of premature death from any cause.

Social media buzz around seed oils

This study calls into question the recent debate around seed oils online, where many influencers have been claiming that they are detrimental to health, and gaining major attention for doing so. Previous research shows these claims are not evidence-based, and the current study provides further evidence that seed oils, such as canola and soybean oils, are not harmful to health and may provide health benefits across the lifespan.

The seed oil claims support a growing narrative that anything that is ‘natural’ is inherently healthier, which can easily lead to false conclusions. In this case, some influencers argue that the industrial process used to produce seed oils makes them an unnatural product, unlike butter.

While this argument makes for compelling social media content and storytelling, it is not rooted in scientific evidence.

The context in which substituting butter for plant oils is beneficial is also important. What often gets conflated on social media is the use of seed oils in everyday cooking and its addition to ultra-processed, “junk” foods, which we already know are not healthy.

Why might people call it junk science?

Dr. Matthew Nagra remarked that the release of this study led to a very emotional response from social media users, leading some people to comment without having read the paper.

Critics of the study may argue that people who consume more butter may be more likely to follow an overall less healthy diet that is associated with worse health outcomes, such as eating more high-fat, and high-salt foods. On the other hand, someone who consumes more plant oils and less butter may be more likely to follow a healthier diet overall, such as the Mediterranean diet.

Dr. Matthew Nagra notes that the people who raised this “healthy user bias” failed to mention that it also applied to seed oils, so “those confounders weren’t enough to completely flip the results.” He also adds that

“The researchers are well aware of these potential confounders and they adjusted for them, limiting their influence on the final results anyway, but the double standard from the critics is worth noting.” The researchers also adjusted for other concerns that critics often point out with these types of studies, such as reverse causation. That said, this study is still only measuring an association between food and health, and cannot determine cause and effect.

Dr. Nagra concludes,

“The fact of the matter is that unsaturated fat rich plant oils are much healthier choices than butter and this is supported by long term randomised controlled trials dating back decades. This is nothing new.”

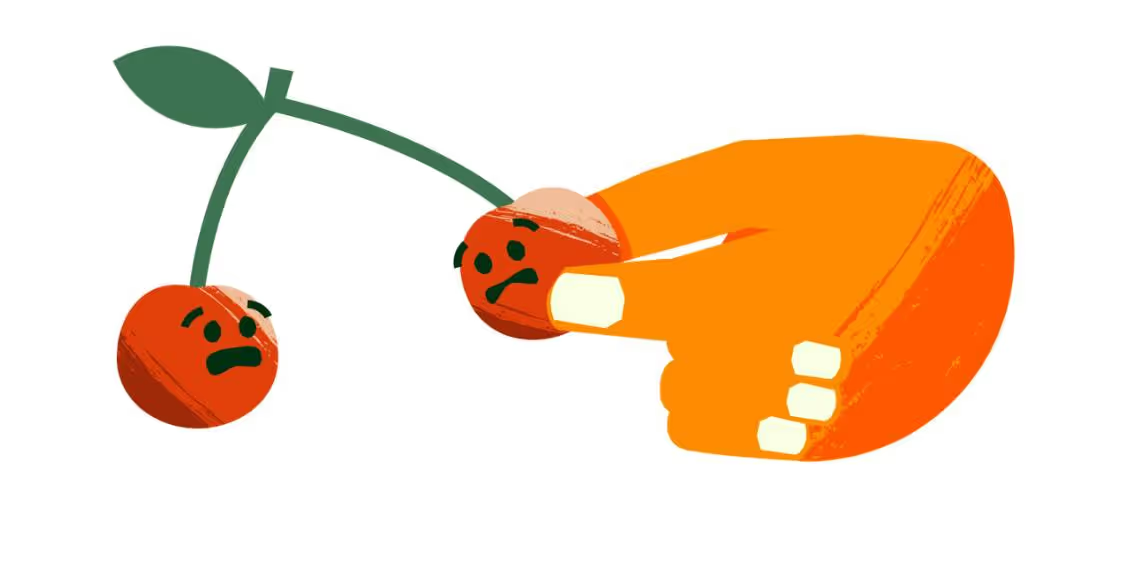

Cherry Picking Fallacy

These comments from Dr. Nagra illustrate another social media trend, where influencers resort to the cherry picking fallacy to push a narrative that their diet is the only way to eat right. The cherry picking fallacy happens when studies which seem to support an argument (or diet) are selected, while others which point in an opposite direction are either entirely ignored, or dismissed because of design flaws, for example.

It can also be seen when influencers pick on such flaws to make the case that researchers are profiting from getting us sick and therefore cannot be trusted, but will then highlight other studies that fit their own narratives.

Social media narratives often sensationalise new studies, but this overlooks the fact that scientific understanding evolves incrementally. All studies have strengths and weaknesses. But they also need to be interpreted in the context of the rest of the evidence that is already available to answer a question or address a topic.

In this case, this new study helps to answer specific questions about the health impact of long-term butter intake, and of substitutions with plant oils to better inform dietary recommendations. But its results are not groundbreaking; they directly align with previous evidence that substituting saturated fats with unsaturated fats leads to better health outcomes.

Why We Focused on Olive Oil and Other Specific Oils:

Some readers have expressed concerns about cherry-picking data by focusing primarily on olive oil and a few other oils. We want to clarify that the selection of oils discussed in this article directly reflects the oils studied in the JAMA Internal Medicine paper. The study did not include sunflower oil or other seed oils commonly labeled as inflammatory. While olive oil is widely recognized as a beneficial oil due to its unique composition and health effects, we acknowledge that other seed oils can vary significantly in their nutritional profiles and health impacts. We strive to provide accurate and contextually relevant information while also acknowledging the complexity of this topic.

Article Update: "Butter vs. Plant Oils: The Debate" - Updated on 22nd March

This article was updated to clarify the scope of the JAMA Internal Medicine study discussed, emphasizing that it specifically focused on olive oil, canola oil, and soybean oil. We also addressed reader feedback regarding the potential perception of cherry-picking data and acknowledged that not all seed oils were covered in the study. We value reader input and are committed to providing transparent, evidence-based information.

Latest fact-checks, guides & opinion pieces

.svg)