Is excess iron a cancer risk? Debunking Dr Eric Berg’s claim with peer-reviewed evidence

Does cast iron cookware increase cancer risk?

Finally, there is no credible evidence that using cast iron pans or taking appropriately prescribed iron supplements increases cancer risk for the general public. Iron from cookware is poorly absorbed, and in fact cast iron cookware has long been used as a low-cost means to help populations at risk of anemia, particularly in developing countries (source, source).

Final take away

Incomplete advice, such as skipping supplements or everyday cookware, fails to consider who most needs iron (those with anemia, women, pregnant people, cancer survivors) and misrepresents the sources that may increase cancer risk (excess haem iron from red and processed and processed meat). It could also lead to unnecessary fear or even guilt among already vulnerable populations, such as cancer patients and cancer survivors, who are likely to be especially sensitive to messaging framed as proven tips “to never get cancer”.

The big picture: misplaced focus

Overemphasised, decontextualised tips like these can make people anxious, lead to needless dietary restrictions, and obscure what has been shown to reduce cancer risk. Indeed it is important to know that it is a matter of reducing, not eliminating risk.

Ultimately, the most effective route to reducing cancer risk is not micromanaging every micronutrient or following a long list of strict, sometimes unsupported, rules. Rather, it's the same advice consistently championed by experts: eat a balanced diet, rich in varied plant-based foods and moderate in animal products; maintain healthy body weight; engage in regular activity; and avoid tobacco and excess alcohol.

We have contacted Eric Berg and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Registered Dietitian Aenya Greene concludes: “Dietary iron causing iron overload in healthy people is very rare, because our bodies tightly regulate absorption. Iron overload mainly becomes a concern in conditions like hereditary hemochromatosis, where this regulation is impaired, or when someone takes unnecessary high-dose iron supplements over a long period of time. Your healthcare provider is unlikely to recommend an iron supplement unless blood tests show you genuinely need one. For the majority of people, their diets won’t lead to iron overload. “

Iron and cancer: a nuanced link

Two further crucial aspects are missing from Eric Berg’s post and are essential for interpreting existing research: the types of iron involved, and the potential complications related to iron deficiency, which might warrant supplementation.

Most iron in your body comes from food and exists in two forms: haem iron, found in animal products like meat and fish, is well absorbed; non-haem iron, present in plant foods and supplements, is absorbed less efficiently (source, source).

Some studies have observed modest, positive associations between increased risk of some cancers and higher intakes of haem iron, the type found in red and processed meats (source). It is worth noting that it can be difficult to isolate red meat intake from processed meat intake in studies. While the latter is classified as a Group 1 carcinogen (causes cancer), red meat is classified as Group 2a (probably causes cancer). This article clearly explains what this means and how this translates in terms of risk.

Other studies show that total dietary iron (haem and non-haem), and non-haem iron (from plants, supplements and cookware) are not linked to higher cancer risk and may even be protective (source, source). This means there is no need to avoid haem-rich foods altogether, but rather it is consistent with public health guidelines to limit red and processed meat, eat plenty of plant-based foods, and maintain a balanced diet.

Bottom line

The bottom line here is that if someone broadly recommends avoiding excess iron, without differentiating between the different types of iron, we end up with a distorted picture.

Major cancer prevention bodies, including the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) and the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR), emphasise that overall dietary patterns are what most influence long-term cancer risk. Diets rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes promote iron balance by providing non-haem iron alongside antioxidants and fibre, which help regulate absorption and reduce oxidative stress. This balance helps to keep iron levels within a healthy range.

Indeed the other side of this equation which gets overlooked by the general advice to skip supplementation, is iron deficiency. Low iron levels can lead to anemia, fatigue, and impaired immune function.

Context matters, because when it comes to social media, we don’t know who the readers are. A lot of people who do take iron supplements have been prescribed them by their doctors, following concerns of deficiency. The Global Burden of Disease 2021 analysis estimated that iron deficiency anemia affects over 1.8 billion people globally, making it the most common micronutrient deficiency in the world.

As a result, seeing a post like this one based on incomplete information could easily lead to fear and undermine trust in healthcare professionals, and potentially impact health.

Nichole Andrews calls particular attention to the risks that skipping supplementation could lead to among cancer survivors, calling instead for tailored guidance from professionals:

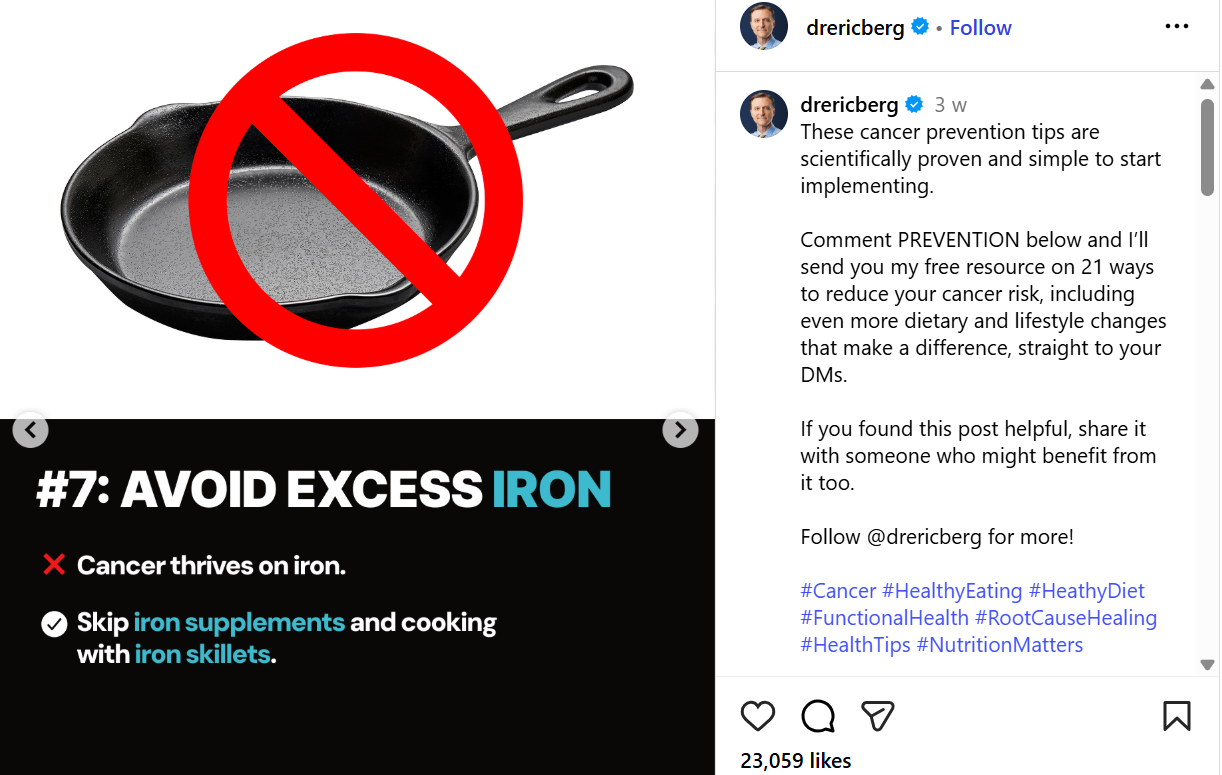

CLAIM: “Avoid excess iron. Cancer thrives on iron. Skip iron supplements and cooking with iron skillets.”

Fact check: Blanket advice to skip iron supplementation and cookware is not supported by scientific evidence, and omits key context about (1) who is concerned by iron overload, (2) how the body regulates absorption, and (3) the different forms of dietary iron.

Presenting this information without explanation distorts the science and can fuel unnecessary fear. Let’s dig deeper to contextualise those claims.

Where does the claim come from?

The hypothesis that iron can fuel cancer growth dates back to the 1950s, based largely on laboratory models and the fact that iron can act as a pro-oxidant. Excess iron facilitates the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can cause DNA damage, a potential pathway to cancer.

The link between excess iron and cancer is strongest in people with iron overload disorders, such as hereditary hemochromatosis (HH), a genetic condition that causes the body to absorb too much iron. In these individuals, iron accumulates in organs like the liver, where it can drive oxidative stress and DNA damage, significantly increasing the risk of liver cancer (source).

Iron metabolism is tightly regulated

It is important to note that in healthy individuals, iron absorption is tightly controlled. The liver helps control how much iron is in your body by releasing a hormone called hepcidin. When you have enough or too much iron, hepcidin tells your body to stop absorbing more; when you’re low on iron, it allows your body to take in more, keeping your iron levels balanced (source, source). In patients with HH however, hepcidin is inappropriately low or ineffective, leading to uncontrolled iron absorption and iron overload (source).

While excess iron can occur in patients without HH, it is most often due to secondary (acquired) causes such as chronic liver diseases, repeated blood transfusions, or excessive iron supplementation. Indeed this study specifies that iron supplementation “can rarely cause significant iron overload and requires substantial iron intake.”

Experts thus caution against simplified advice found on social media. Nichole Andrews is a registered dietitian with extensive experience working with cancer patients and cancer survivors. She feels that the advice presented in Eric Berg’s post is fear-based, not evidence-based. She further explains:

Research does not support a blanket rule that “iron feeds cancer.” Some cancers alter iron regulation, but this does not mean that removing dietary iron or cookware is protective.

People [who actually need to avoid iron are those] with medically diagnosed iron overload (ex: hemochromatosis) or transfusion-related iron excess. This is rare and always monitored by a clinician. This is not something survivors diagnose themselves from an Instagram post.

Cancer cells use iron. So do your red blood cells, your immune system, your mitochondria, and your recovery pathways.

Avoiding iron without medical indication is harmful for many survivors. Cooking in cast iron is safe.

And no credible evidence supports that dropping iron will “prevent cancer” or “starve cancer.”

The only evidence-based approach:Check your labs. Personalize your plan. Stop letting influencers dictate your medical care.

Iron deficiency is extremely common in cancer survivors. Treatment, blood loss, poor intake, inflammation, and chemotherapy all drive iron deficiency and anemia. Correcting that deficiency improves energy, cognition, strength, and treatment tolerance. Stopping needed iron can worsen fatigue, delay recovery, and reduce quality of life.

Standard oncology guidelines recommend treating iron deficiency, not avoiding iron.

Major cancer groups (ASCO, ESMO, NCCN) emphasize the following:

• Check labs

• Identify true deficiency

• Treat with oral or IV iron when indicated

There is no guideline recommending survivors stop physician-prescribed iron, and no guideline warning against cast iron cookware.

If someone claims something increases cancer risk, check whether they cite credible studies and explain clearly for whom, under what circumstances, and at what dose or exposure this applies. And always be cautious with absolutes like always, never, or the most dangerous; science rarely speaks in extremes.

On multiple occasions, most recently on November 11, Eric Berg, D.C., a popular social media health influencer and chiropractor, has repeated claims in widely-shared posts entitled “How to never get cancer.”

Among his “scientifically proven tips,” Eric Berg singles out iron and advises to "avoid excess iron," suggesting that people should skip iron supplements and avoid cooking in iron skillets. Other recommendations include intermittent fasting, following a low-carb diet, and exercising.

This particular tip regarding excess iron appears to have generated significant confusion in the comments, with followers expressing concern as several were prescribed iron for anemia. This fact-check focuses on the implications and scientific evidence behind this particular claim.

Iron metabolism is regulated for most people, and both excess and deficiency may carry risks. There is no evidence linking cast iron to increased cancer risk. The broad advice from this single post is incomplete, and may cause harm if it leads people to skip prescribed treatment.

By using decisive language without context or knowledge of viewers’ health status, social media posts like this risk undermining medical advice and encouraging vulnerable individuals to skip needed treatment through supplementation, potentially worsening health outcomes.

Cut your pet’s carbon paw print: The benefits of sustainable, animal-free pet food

As concern for the planet and animal welfare grows, many pet owners are rethinking what’s in their dog and cat food bowls. Two major studies published in 2025 show there’s robust science—and strong motivation—behind the move away from meat-based pet diets. Here’s what the latest research found, why it matters, and how making the switch can benefit pets, farmed animals, and the environment.

What do the studies reveal about plant-based pet food?

The first study surveyed nearly 2,700 dog guardians globally. It found that 43% of those feeding conventional or raw meat diets would consider switching to a more sustainable alternative (such as vegan, vegetarian, or cultivated meat). Among these alternatives, cultivated meat-based options were the most favoured (24%), followed by vegetarian (17%) and vegan (13%) diets. Nutritional soundness and proven health outcomes were the top priorities for guardians considering a switch.

The second study surveyed 1,380 cat guardians worldwide. Even among cat owners—whose pets are obligate carnivores—more than half (51%) would consider a sustainable diet, including cultivated meat or vegan options. As with dogs, cultivated-meat-based diets were most popular (33%), followed by vegan alternatives (18%). The leading decision factors closely mirrored the dog study—guardians prioritised pet health (83%) and nutritional soundness (80%) when evaluating new diets.

Are plant-based diets healthy for dogs and cats?

Both studies highlighted a major shift in attitudes: many pet owners are open to change when science supports it.

Recent research shows that modern, commercial plant-based pet foods can offer nutrients comparable to meat-based diets. For dogs, analyses of UK pet foods found plant-based products met almost all essential nutritional standards, with minor differences easily addressed by supplementation. Cats are more complex, but studies show that vegan cat foods—properly formulated and supplemented with crucial elements like taurine—can support feline health as effectively as meat-based diets.

In fact, health surveys found vegan-fed cats had slightly fewer vet visits and health disorders, and less medication use, than cats fed standard meat diets.

How does pet food impact the planet?

Pet food is a major driver of factory farming and environmental damage. Globally, cats and dogs consume at least 9% of all farmed animals, and 20% in high pet-owning nations like the US, increasing demand for intensive animal agriculture. This industry is a top contributor to deforestation, water use, and greenhouse gas emissions.

Research comparing pet food footprints found that plant-based diets are dramatically better for the planet:

- Up to 90% lower greenhouse gas emissions than beef-based pet foods.

- Land use for plant-based pet food is a fraction of that for meat diets.

- Vastly reduced water consumption and potential for habitat restoration.

Switching your pet to a nutritionally sound vegan or vegetarian diet can cut their carbon “paw print” and help fight climate change, without compromising their health.

What about animal welfare?

Pet food demand results in billions of farmed animals being slaughtered each year—most raised in close confinement, often with minimal opportunity for natural behaviours, and are often subjected to painful procedures such as tail-docking or beak-trimming, without painkillers. Nearly all are then killed at a very premature stage of life when marketable body weights are reached or productivity declines. Reducing meat in pet food directly lowers demand for factory-farmed animals, sparing billions of animals from suffering.

Study co-author Professor Andrew Knight emphasised the broader implications: “According to recent research, our dogs and cats together eat a significant proportion of all animals raised for food. Plant-based or cultivated meat-based dog and cat diets have the potential to revolutionise the pet food industry, and to reduce negative effects on both the environment and farmed animals.”

How can pet owners make the switch to sustainable pet food?

Making the change is easier than ever:

- Choose reputable brands offering nutritionally complete plant-based foods for dogs and cats—look for compliance with standards like those published by the international authorities FEDIAF and AAFCO.

- Transition gradually, mixing in more plant-based food over 1–2 weeks to help pets adjust.

- Monitor your pet’s health - you’re more likely to see benefits than problems, but see a veterinarian if you have any concerns. Be aware, however, that most vets are not yet aware that nutritionally sound vegan diets are now commercially available, nor of the recent scientific evidence supporting their use, and so may be opposed to this dietary choice.

- Even reducing meat-based pet food by half yields substantial benefits. You don’t have to go all-in at once.

What do these results mean for the pet industry?

These studies make it clear: the future of pet food will be built on trust, science, and honesty. More pet guardians want to understand exactly what’s in their pets’ bowls, how the food is made, and whether it truly supports good health. For brands, this means going beyond clever marketing—nutritional quality, clear labelling, and sharing real-world health results all matter more than ever.

Veterinarians and animal-welfare advocates also have a key role to play. The research shows that many pet owners are willing to try sustainable diets, but only when they have reliable, evidence-based advice they can trust. Open conversations and up-to-date knowledge will help guardians feel confident about alternative options.

As more people recognise the big environmental impact of conventional pet food, it’s obvious that change isn’t just possible—it’s already happening. The next step? Scientists, vets, and the pet food industry working together to give pets the healthiest diets with the smallest paw print on the planet. This moment offers a real opportunity to rethink what “good pet food” means for everyone—animals, people, and the world we share.

Study co-author Billy Nicholles explains that: “These findings are of value to the rapidly growing pet food alternatives industry, enabling pet food companies to accelerate their growth and acquire new customers through evidence-based, targeted outreach.”

The bottom line

The science shows nutritionally complete, plant-based pet foods can support canine and feline health. Adopting these diets helps curb climate change, reduce animal suffering, and support a more sustainable food system—while still providing pets the nutrition they need.

For caring guardians, it’s a simple decision with lasting impact. Moving away from food made from farmed animals isn’t just good for your pets; it’s a step toward a healthier, more compassionate world.

Should you eat broccoli stalks? Rethinking food waste, one stem at a time

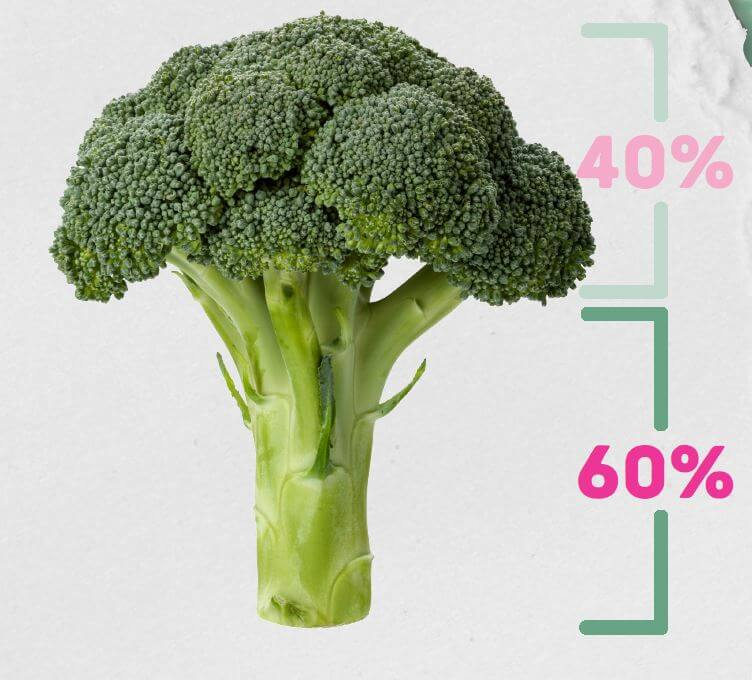

Each year, around 119,000 tonnes of broccoli are lost or wasted in the United States alone. Globally, an estimated 60 to 75 percent of broccoli production is discarded as waste during harvesting, with much of this coming from the parts of the vegetable we've been conditioned to overlook. In New Zealand, over 2,500 tonnes of broccoli stalks and leaves are thrown away annually. With 37 percent of people admitting they throw away broccoli stalks, we're not just wasting food—we're discarding nutrition, money, and squandering precious environmental resources.

The question isn't whether broccoli stalks are edible. They absolutely are. The real question is: why have we been throwing away such a valuable part of this vegetable for so long?

The hidden proportion: how much broccoli are we really wasting?

When you pick up a head of broccoli at the supermarket, you might be surprised to learn just how much of what you're paying for ends up in the bin. In practical terms, the stalk can account for around 60% of the weight of the broccoli you purchase. This means that when you throw away the stalk, you're discarding nearly two-thirds of the vegetable you've just paid for.

Nutritional treasure hiding in plain sight

Perhaps the most compelling argument for eating broccoli stalks is what they contain. Far from being nutritionally inferior to the florets, broccoli stems hold their own—and in some cases, exceed—the nutritional value of their more celebrated counterparts.

Broccoli stalks contain comparable levels of calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, manganese, and B vitamins to the florets. A portion of broccoli stalk provides 52 milligrams of vitamin C—more than half the daily recommended intake for most adults—along with significant amounts of vitamin A, folate, iron, and fiber. One portion of cooked medium stalk delivers 22 percent of your daily folate requirement, 9 percent of your daily fiber requirement, 5 percent of potassium, 7 percent of vitamin A, and an impressive 94 percent of vitamin K.

The fiber content is particularly noteworthy. Broccoli stems are rich in insoluble fiber, which supports digestive health, helps regulate blood sugar levels, and promotes satiety. Some sources indicate that broccoli leaves actually contain a higher concentration of certain nutrients, particularly fiber, compared to the florets.

Research comparing different parts of the broccoli plant found that while florets contain higher levels of certain glucosinolates (the compounds linked to broccoli's anti-cancer properties), stems have their own advantages. Broccoli stems contain about 10 to 20 times more glucoerucin than floret tissue, and the stems can even contain slightly more calcium, iron, and vitamin C than florets.

The nutritional profile is remarkably similar overall. The stems provide protein, vitamins, minerals, and beneficial plant compounds—essentially all the good stuff you're eating broccoli for in the first place. The main difference lies in texture rather than nutrition, and that's easily addressed with proper preparation.//

The environmental cost of throwing food away

To understand why eating broccoli stalks matters, we need to look at the broader environmental picture. Food waste has emerged as one of the most pressing environmental challenges of our time, with far-reaching consequences that extend well beyond overflowing bins.

Globally, food loss and waste account for 8 to 10 percent of annual greenhouse gas emissions—nearly five times the total emissions from the aviation sector. If food waste were a country, it would rank as the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, after only China and the United States. In the United States alone, surplus food generates the same amount of greenhouse gas emissions as driving 54 million cars annually.

When food ends up in landfills, it decomposes anaerobically—without oxygen—producing methane, a greenhouse gas that is significantly more potent than carbon dioxide in the short term. Food waste in US landfills produces nearly three million metric tons of methane each year, representing 10 percent of the country's total annual methane emissions.

The environmental burden extends beyond emissions. Food production requires enormous inputs of land, water, energy, and fertilizer. When we waste food, we waste all of those resources too. Food waste uses up almost a third of the world's agricultural land and accounts for about 16 percent of the environmental impacts of the EU food system, including 16 percent of CO₂ emissions, 12 percent of water use, and 16 percent of land use.

For broccoli specifically, every discarded stem means squandered irrigation water, wasted agricultural inputs including fertilizers and pesticides, and unnecessary carbon emissions from cultivation, transportation, and disposal. The 119,000 tonnes of broccoli wasted annually in the US alone represents a massive environmental cost that could be significantly reduced if we simply ate more of what we're already growing.

The next time you consume broccoli, consider including the stems as well as the florets. It is a common misconception that broccoli stalks are inedible; in fact, they are highly nutritious and contain vitamins, fibre, and antioxidants. Incorporating the stems into meals is an effective way to reduce food waste while maximising the vegetable’s nutritional value. - Aenya Greene, foodfacts.org Dietician

From rubbish bin to dinner plate: how to eat broccoli stalks

The good news is that incorporating broccoli stalks into your cooking is remarkably simple. The key is understanding how to prepare them properly to achieve the tender, delicious texture they're capable of.

How to prepare broccoli

The outer layer of broccoli stems can be tough and fibrous, which is likely why many people assume the entire stalk is inedible. However, once you peel away this outer skin—which comes off surprisingly easily—you'll discover a tender, mild-tasting core that's similar in texture to the heart of a cabbage stem or kohlrabi.

To prepare broccoli stalks, start by cutting off the florets where they meet the main stem. Trim about an inch from the bottom of the stalk, and use this cut to begin peeling back the thick outer skin with a sharp knife or vegetable peeler. The skin peels away almost by itself once you get started. Peel all the way up the stalk until you reach the point where it becomes more tender.

Once peeled, the possibilities are endless.

How to cook broccoli

Broccoli stalks are incredibly versatile and can be prepared using virtually any cooking method:

Stir-frying: Cut the peeled stalks into thin slices or matchsticks and stir-fry them with garlic, ginger, soy sauce, and sesame oil. They cook quickly and develop a pleasant, slightly sweet flavor.

Roasting: Slice stalks into rounds or sticks, toss with olive oil and seasoning, and roast at high temperature (around 200°C/400°F) until tender and slightly caramelized at the edges. The roasting brings out natural sweetness and creates delicious crispy edges.

Steaming and boiling: Place sliced stalks in the bottom of a pot with water, then place the florets on top. Both parts finish cooking at the same time.

Air frying: Peel and cut stalks into fry-shaped pieces, season with garlic powder and salt, and air fry at 200°C/400°F for 15 to 20 minutes until golden and crispy. Serve with your favorite dipping sauce for a healthy snack.

Raw applications: Finely julienne or shred peeled stalks to add to slaws, salads, or vegetable platters. The texture is crisp and refreshing, with a mild, slightly sweet taste.

Soups and purées: Chop stalks and add them to soups, stews, or blend them into purées for pasta sauces. Broccoli stalk soup is a classic way to use the whole vegetable.

The flavor is milder and slightly sweeter than the florets, making stalks an excellent addition to dishes where you want broccoli's nutritional benefits without an overpowering taste.

Beyond broccoli: rethinking what we throw away

The conversation about broccoli stalks is really a conversation about something much larger: our relationship with food waste and the arbitrary decisions we've made about what's "edible" and what's "waste."

Researchers examining discarded food have found that between 52 and 71 percent of total food thrown away is actually edible. We discard carrot tops, celery leaves, cauliflower stems, chard stalks, and countless other nutritious plant parts simply out of habit or lack of knowledge. This root-to-stem approach to cooking recognizes that many of the parts we throw away contain equal or greater nutrition than the parts we eat, and that using the whole vegetable reduces waste, saves money, and adds variety to our diets.

A simple change with meaningful impact

Should you eat broccoli stalks? The evidence overwhelmingly says yes. They're nutritious, delicious when properly prepared, and throwing them away wastes food, money, and environmental resources at a time when we can afford to waste none of these things.

When 37 percent of people throw away broccoli stalks, that represents a collective opportunity for change. The next time you're preparing broccoli, consider pausing before you toss that stem. Peel it, slice it, cook it alongside the florets. Share what you learn with others who might not know that broccoli stalks are edible.

Food waste is a complex global challenge, but eating broccoli stalks is a simple, concrete action that addresses it. It's a small step that acknowledges the true value of our food—not just the parts we've been taught to eat, but all the nutritious, flavorful parts that deserve a place on our plates rather than in our bins.

Ultra-processed foods, plant-based meat and your health

The conversation around food processing has become front-page news, just as plant-based meat products have become a regular sight on our supermarket shelves.

With many people lacking an understanding of plant-based meat’s nutritional profile or how it is made – not to mention misleading headlines – it is easy to see why the debate around processing has led to confusion about the health profile of plant-based meat.

Despite generally having a good nutritional profile, and offering a simple swap for conventional processed meat, plant-based meat is often considered an ultra-processed food.

The subject of ultra-processing can often be complex. While most of the foods in the UPF category are undoubtedly unhealthy in excess, their categorisation is not based on nutritional criteria, and some of them have good nutritional profiles.

The system that gave us the term ultra-processed foods – a classification system called Nova – was developed to look at eating patterns on the population level and explore the food system shifts that have led to growing rates of chronic disease and diet-related ill health in several countries.

The Nova system suggests that a shift away from traditional home-cooked meals and towards convenient, cheap, mass-produced options (characterised as UPF) has played a role in driving negative health outcomes.

But this can’t explain the whole story – after all, a home-made cake may not be ultra-processed, but it is not advisable to eat every day.

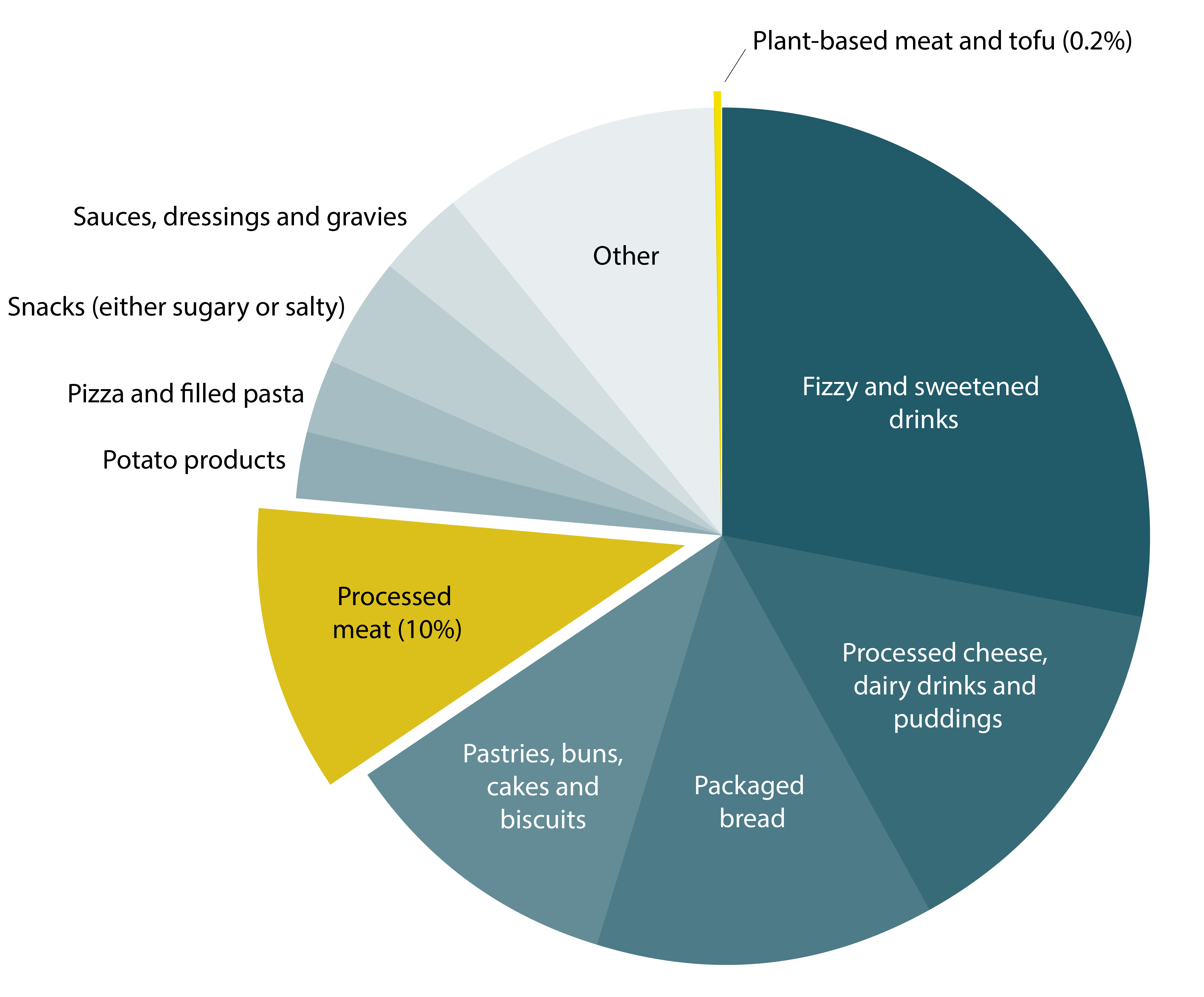

Foods falling into the UPF category also generally have poor nutritional profiles, are quick to buy and ready to eat, and are a much lower effort barrier to eating too much of them than if you had to make them from scratch. The foods making up the bulk of high-UPF diets in research tend to be high in salt, fat and sugar, and low in fibre – such as hot dogs, fizzy drinks, milkshakes, salty snacks, cakes and pastries.

It therefore makes sense that people with the highest proportion of their diets coming from these foods generally have worse outcomes, particularly when considering the UPF group by definition does not contain any fresh fruit and vegetables – an important part of any healthy, balanced diet.

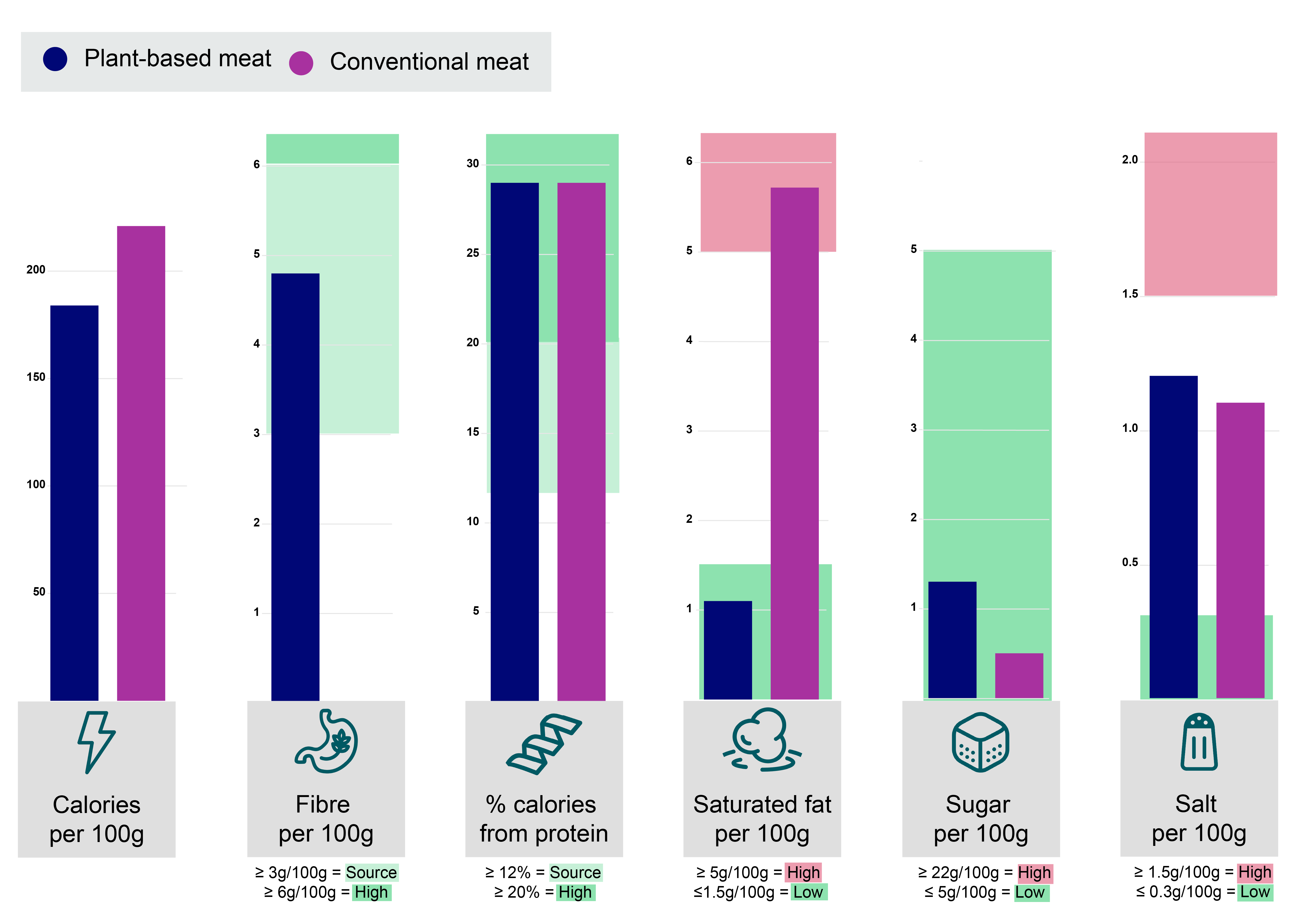

However, not all UPFs have a poor nutrient profile. Plant-based meat is a key example – generally being low in saturated fat and sugar, high in protein and a source of fibre.

Our guide, developed in collaboration with the Physicians Association for Nutrition International, aims to shine a light on the nuances and underlying evidence surrounding the complex topic of plant-based meat and the ultra-processing debate.

How plant-based meat can support healthier, more sustainable diets

Many European countries’ national dietary guidelines recommend the limiting of processed meat consumption, but the constant time pressures of modern lifestyles, coupled with an abundance of cheap, tasty products like bacon and ham, can make it hard to keep intake within recommended limits.

Plant-based meat offers a simple swap that is low in saturated fat (while processed meat is generally high) and offers a source of fibre (while conventional meat has none) while offering similar levels of protein.

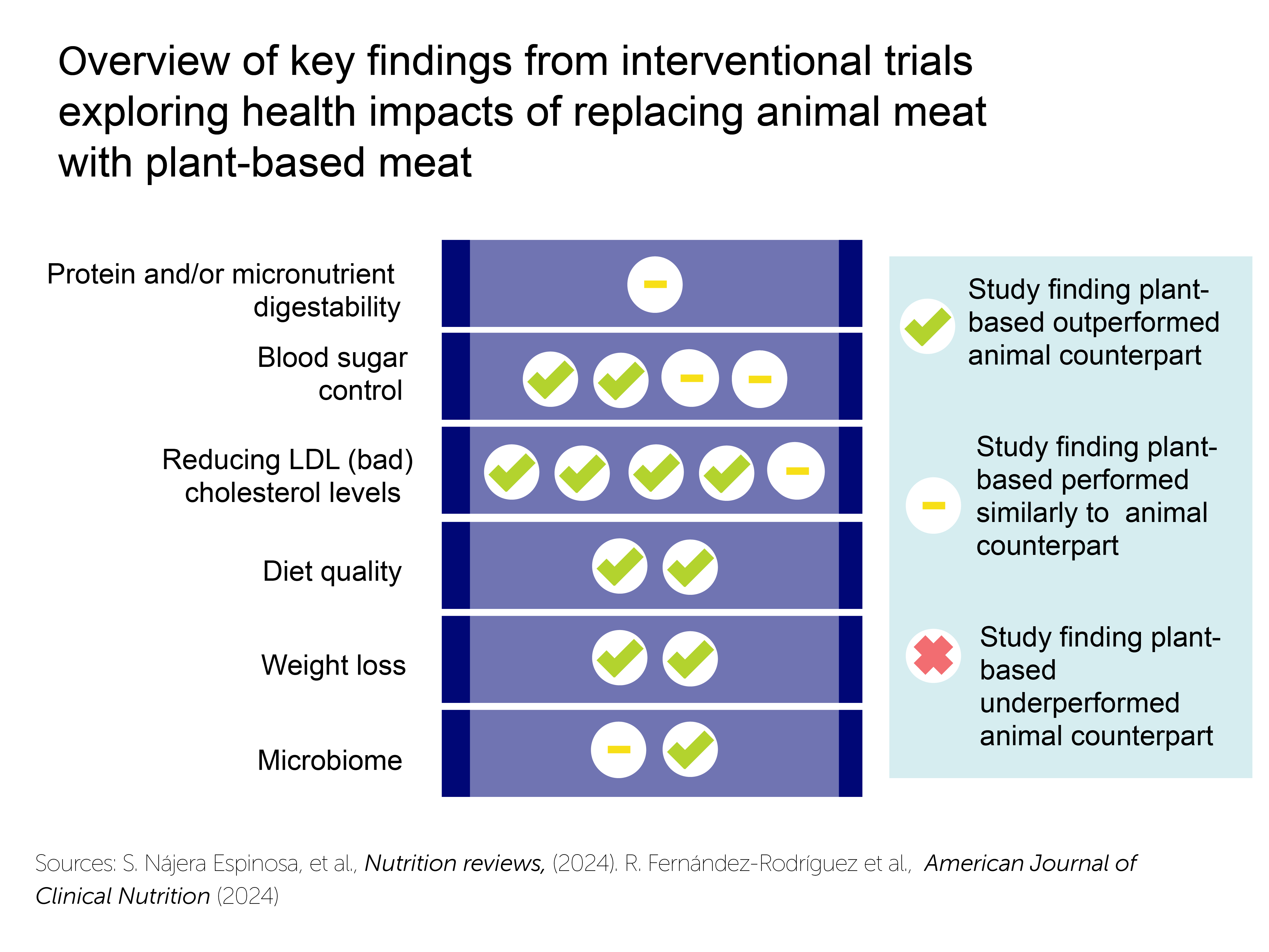

The evidence we have so far on plant-based meat is still at a relatively early stage, but what we do know is promising:

- It is well established that lower intakes of saturated fat are associated with reduced cardiovascular disease risk, and higher intakes of fibre are associated with several health benefits, including better weight management.

- The results of trials to date on the impact of swapping conventional meat with plant-based meat show benefits in line with these features of its nutritional profile – with the most consistent differences observed being reduction of LDL cholesterol, and modest weight loss in those above the recommended healthy weight. This is based on a systematic review and meta analysis of 7 randomised controlled trials comprising 369 adults.

- These findings are very different from studies looking at the impacts of diets high in UPF at the population level, which tend to find that high consumption of foods within the UPF category as a whole is associated with higher rates of obesity and cardiovascular disease.

In addition to this, there are several reasons why it is unlikely that available observational UPF research can be usefully applied to plant-based meat:

- Plant-based meat has a very different nutritional profile from the majority of foods in the UPF category. In particular, it is low in sugar and saturated fat, a source of fibre and high in protein.

- Plant-based meat makes up a vanishingly small percentage of calories eaten in the datasets used in most UPF research.

- The long-term nature of observational UPF studies means that the food diaries they are based on are often over 10 years old, use food frequency questionnaires that do not provide sufficient information for researchers to distinguish between plant-based meat and more traditional foods like tofu, and date back to a time when most modern plant-based meat options did not exist.

The best diet is one you can stick to

There is no single pathway to a healthy lifestyle, and different approaches clearly work better for different kinds of people. A key opportunity area for plant-based meat lies in its ease of adoption and ability to help reduce the current overconsumption of conventional processed meat, a subgroup of UPF with particularly strong associations with negative health outcomes when eaten in excess, observed in studies from Europe, the US and South Korea.

Plant-based meat is sometimes viewed as a niche food for those already following plant-rich diets like vegetarians, but its primary potential for public health lies in broader mainstream adoption.

It has the largest potential for the many people who enjoy meaty meals, eat less fibre and more processed meat than recommended, and don’t want to completely overhaul their diets, preferring options that fit within their existing daily routines and meals.

Increased availability of tasty, affordable, nutritious plant-based meat designed to appeal to these people could help improve diet quality and make plant-based foods more approachable and easier to prepare – currently a barrier to adoption for many people.

A study exploring the patterns in diet change of the ‘champion households’ for diet sustainability in the UK found two distinct patterns amongst the groups who most effectively reduced the greenhouse gas emissions of their diets. All of those successfully reducing emissions significantly reduced their intake of meat, but some switched meat for dairy, and some increased their intake of plant-based foods.

While both groups reduced the carbon footprint of their diet, only the plant-based increasing group saw co-benefits with health.

The meat to dairy group overall saw a decline in diet quality: there was no increase in consumption of vegetables or legumes, while foods that were increased varied significantly in nutritional profile. Dairy products saw by far the largest increases, followed by smaller increases in plant-based milk and fruit. Increases were also seen convenience food groups commonly associated with the UPF group: desserts, snacks and bakery.

Meanwhile, those taking the plant-based approach to increasing their intake reduced the environmental impact of their diets while also seeing improvements in diet quality. Vegetables, plant-based milk and fruit saw the largest increases in intake, followed by plant-based meat, legumes, nuts and seeds. In this group, unlike the meat to dairy group, common energy-dense foods such as confectionery, desserts, pre-prepared foods and bakery also fell.

This suggests that adoption of plant-based meat is generally more closely associated with the positive dietary shifts towards healthier and more sustainable diets than it is to other foods in the UPF group, and far from reinforcing the ‘status quo’ as is often suggested, they could make plant-rich diets more generally accessible and easier to stick to.

The role of fortified, high-protein plant-based foods in safeguarding food security

We know that in the shift towards healthier, more sustainable diets, we urgently need to eat more plant-based foods. But it is also important to remember that, at present, for most of the European population, animal-based foods are currently a primary source of several important nutrients like B12, zinc, iodine, calcium and long-chain omega 3s.

Several of these nutrients are not inherent to animal-based foods – and their presence and consistency are often the result of fortification added to animal feed and farming practices that boost the content of these nutrients.

One example is iodine. Not naturally found in dairy in high quantities, iodine is routinely added to cow feed and is also used as the base of some disinfectants used in milking, which consequently provide iodine content commonly found in dairy products.

B12 – often associated with animal products – is another example. B12 is only made by certain types of bacteria, and neither plants, animals nor fungi can naturally produce it. These other organisms must therefore get it either from diet or, in the case of ruminant animals, from symbiotic relationships with gut bacteria.

Fortified animal feed and veterinary supplementation are therefore the original source of much B12 in animal-based foods eaten in Europe, particularly in the case of the meat and eggs from birds and non-ruminants. In the wild, concentrations can also vary significantly between ruminant animals based on soil composition, so consistency is ensured in farmed ruminants through the routine provision of supplementation with cobalt to support these gut bacteria or direct supplementation with B12.

In contrast, consistency of fortification in plant-based meat and dairy is limited, and needs to be improved.

While fresh vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts and wholegrains contain a wide variety of health-promoting nutrients, plant foods also often contain compounds that make certain nutrients more difficult to digest than equivalents from animal or fungi-based foods – sometimes called ‘antinutrients’.

This is true for both micronutrients like calcium, zinc and iron, and also for protein. While these needs can usually be met by eating a larger volume of food, or by supplementing or planning diets more carefully, fortified plant-based foods with better bioavailability may make it easier for people less knowledgeable about nutrition, or people less able to eat larger volumes (eg older people) to get everything they need from their diet.

Certain processing approaches show promise in overcoming these challenges, and this is a key area where more research is needed.

Besides the environmental challenges associated with the current overconsumption of animal-sourced foods, our overreliance on meat and dairy for key nutrients at the population level also presents risks to food security. The ongoing bird flu epidemic is a prime example of this, underlining the importance of protein diversification in safeguarding affordable access to nutritious diets.

As the growing impacts of climate change on agriculture put increasing pressure on our food systems, the higher resource intensity of animal-source foods makes them susceptible to supply shocks and price increases. Nutrient-dense plant-based options that are tasty and affordable could therefore play a central role in a more resilient food system.

Without a nuanced approach to processing, however, these potential advantages may be neglected and the considerable opportunities offered by plant-based meat and other high-protein, fortified plant-based foods missed.

A more nuanced way to think about processing

A blanket message to “avoid all ultra-processed foods” risks hiding important differences between products, overlooking nutritionally useful options like fortified plant-based foods and confusing consumers, especially when time, cost and convenience all matter.

Instead, the focus should be on improving overall diet quality, and limiting UPFs that are clearly linked with harm when eaten in excess, such as sugary drinks, sweets, crisps, cakes, pastries and processed meat. Plant-based meat has clear potential to help achieve both of these goals.

Plant-based meat is not a cure-all, but nor is it simply “just another UPF”. When used thoughtfully, it can be a useful tool – alongside broader dietary shifts – in moving towards diets that are both healthier and more sustainable, without demanding an overnight transformation of how people eat.

When nutrition advice misses the mark: Why taxing baked beans ignores the real barriers to healthy eating

When Professor Chris van Tulleken recently appeared before the Commons Health Committee calling for taxes on baked beans, brown bread, fish fingers, and Coco Pops, it sparked an important conversation - but one that glosses over a critical reality. For many families, these everyday foods provide affordable sources of protein, fibre and essential nutrients. Having the luxury of choice is a privilege that is not always available to those living with food insecurity.

As a Registered Associate Nutritionist, I support genuine efforts to tackle diet-related disease. But the conversation surrounding ultra-processed foods has become dangerously disconnected from how the general population actually eat. It's time we talked honestly about why simplistic solutions like taxation miss the point entirely.

The uncomfortable truth about UK food affordability

The Broken Plate 2025 highlights a growing inequality in our food system. We know that healthier foods are more than twice as expensive per calorie compared to less healthier options. Over the past two years, the price of healthier foods has risen at twice the rate of less healthy ones. Additionally, The Broken Plate 2025 report demonstrated that the most deprived fifth of the UK population would have to spend 45% of their disposable income on food to meet the UK government's healthy eating recommendations. For households with children in this group, that figure rises to 70%. By contrast, the wealthiest fifth needs to spend just 11% of their income. With 21% of the UK living in poverty, this makes it increasingly challenging for many UK households to afford a healthy diet.

The conversation also overlooks a fundamental issue: access. Around one in ten deprived areas in the UK are classed as food deserts, affecting an estimated 1.2 million people. These are not just neighbourhoods without supermarkets. They are communities where residents face multiple barriers to accessing affordable and nutritious food. This includes limited public transport in rural areas, digital exclusion that prevents people from using online grocery services and physical barriers faced by disabled people. Low-income households and older adults are particularly affected, often relying on nearby convenience stores where healthier options are limited and significantly more expensive than in larger supermarkets.

For a pensioner without a car in a rural area, a parent working two jobs with no time to cook from scratch or a family in an area with limited public transport, telling them to "eat more fruit and vegetables" isn't helpful advice, it is a privilege they do not have access to.

The fibre crisis has a much simpler solution

Here’s another crucial point that’s often overlooked: the UK is not eating enough fibre. According to the latest National Diet and Nutrition Survey only 4% of UK adults meet the recommended intake of 30 grams of fibre per day. Among children and teenagers, 96% fall short of this target.

For many people, the small amount of fibre they do consume may come from foods such as baked beans, which provide around 5 grams per half tin. Baked beans remain one of the most accessible and affordable ways for households to increase their fibre intake. The Food Foundation is even running a national campaign to promote the benefits of beans. Messaging that discourages or criticises the consumption of baked beans risks confusing the public and undermining efforts to improve fibre intake across the UK population.

The nuance that gets lost in headlines

There’s an important distinction that often gets lost in the discussion: not all ultra-processed foods are created equal. While some baked beans contain additives such as modified cornstarch or spice extracts (which can classify them as ultra-processed) they provide valuable nutrients and are an affordable source of fibre and protein for many people.

Grouping baked beans with products such as foods contain high levels of fat, salt and sugar, oversimplifies the issue and risks misleading the public. Nutrition science is about context and balance, not blanket statements. A tin of beans on wholemeal toast is a genuinely nutritious, accessible meal that millions of people rely on. Labelling such foods as problematic can undermine public health messaging and cause unnecessary guilt around practical, nourishing choices.

Why expertise matters—and who gets heard

Public health policy should be grounded in evidence and shaped by those who understand both the science and the lived realities of the UK population. When high-profile figures call for taxation or restrictions without acknowledging the wider determinants of health, it shifts blame onto individuals and stigmatises affordable foods, rather than addressing the real issue: a food system that makes healthy choices inaccessible for millions.

It is also important to recognise that having a “Dr” title does not automatically mean someone is qualified to speak on nutrition. Nutrition is a complex and nuanced science that requires years of dedicated study and supervised practice. Registered Nutritionists (AfN), Dietitians and researchers who work directly with low-income communities bring this depth of expertise, along with an understanding of the social and economic factors influencing diet. Their voices deserve as much - if not more - weight in these discussions than those of television personalities.

What actually needs to happen

Taxation of affordable staple foods will not reduce obesity or diet-related disease. It will simply make survival harder for the people already struggling most. I am yet to find a single study showing that foods such as baked beans or brown bread contribute to obesity. These are everyday, nutrient-dense staples that provide fibre, protein and energy at a low cost.

If we are serious about improving public health, we need policies that address the root causes: wages that have not kept pace with living costs, a food system that makes cheap calories more readily available than nutritious ones and communities where fresh food is genuinely inaccessible.

This means ensuring that minimum wage and benefits reflect the true cost of living. It means investing in local food infrastructure and transport links to underserved areas. It means reformulating products to reduce sugar and salt where evidence supports it. And it means introducing price supports for fruits, vegetables and legumes so they become cheaper than junk food, not more expensive.

Most importantly, it means having honest conversations with registered and qualified nutrition professionals who understand both the evidence and the real barriers people face.

The bottom line

We all want people to eat well and live healthier lives. But that vision needs to be rooted in reality. For now, baked beans on toast remains a sensible meal - quick, nutritious, filling and genuinely affordable. Let's talk about how to make nutritious food universally affordable and how to rebuild a food system that works for everyone, not just those who can afford artisan sourdough and organic vegetables.

Until that happens, taxing the foods that help people stay fed cannot be called public health policy. It reflects a position of privilege that overlooks the realities faced by millions. The real question is what the government and influential public figures are doing to make food more affordable and accessible for everyone.

“I changed my diet and got pregnant”: What’s the evidence behind these claims?

Claim 2: Doctors don’t tell women that diet matters

How is this claim made?

The article quotes the woman saying: “Doctors say diet doesn’t matter, but I believe it still does.” Negative experiences whereby people’s concerns have been dismissed by health professionals are real, and should not be dismissed. However, by adding that “Molly decided to take matters into her own hands,” and by not considering other viewpoints, readers might be left with the impression that this is common practice.

This framing suggests that healthcare professionals dismiss nutrition as irrelevant to fertility, implying that women must rely on self-directed diet changes or social media advice instead.

The article also implicitly challenges established dietary guidelines, which consistently emphasise balance and moderation, by using the subheadline: “Molly Brown now loads up her plate with bacon and butter and credits it for making her healthier.” Later, it links to a video of a woman eating entire sticks of butter, imagery that reinforces the appeal of dietary extremes rather than the evidence-based principle of balanced nutrition.

How is this claim reinforced by omission?

By omitting information about current dietary guidelines and how they are formulated, the article misrepresents what doctors actually say. This is an example of a straw man argument: it constructs a simplified version of medical advice only to dismiss it.

In reality, public-health agencies and fertility specialists acknowledge that diet can play an important role in reproductive health. The NHS clearly advises:

“If you're trying to get pregnant, it’s important to take folic acid every day, eat a healthy diet, and avoid drinking alcohol. This will help your baby develop healthily.”

Doctors also recommend maintaining a balanced weight, monitoring vitamin D and iron levels, and avoiding restrictive diets during conception and pregnancy. By omitting this, the article risks encouraging readers to distrust professional guidance and “take matters into their own hands” in ways that could lead to nutritional deficiencies or other health risks.

Final take away: seeing the bigger picture

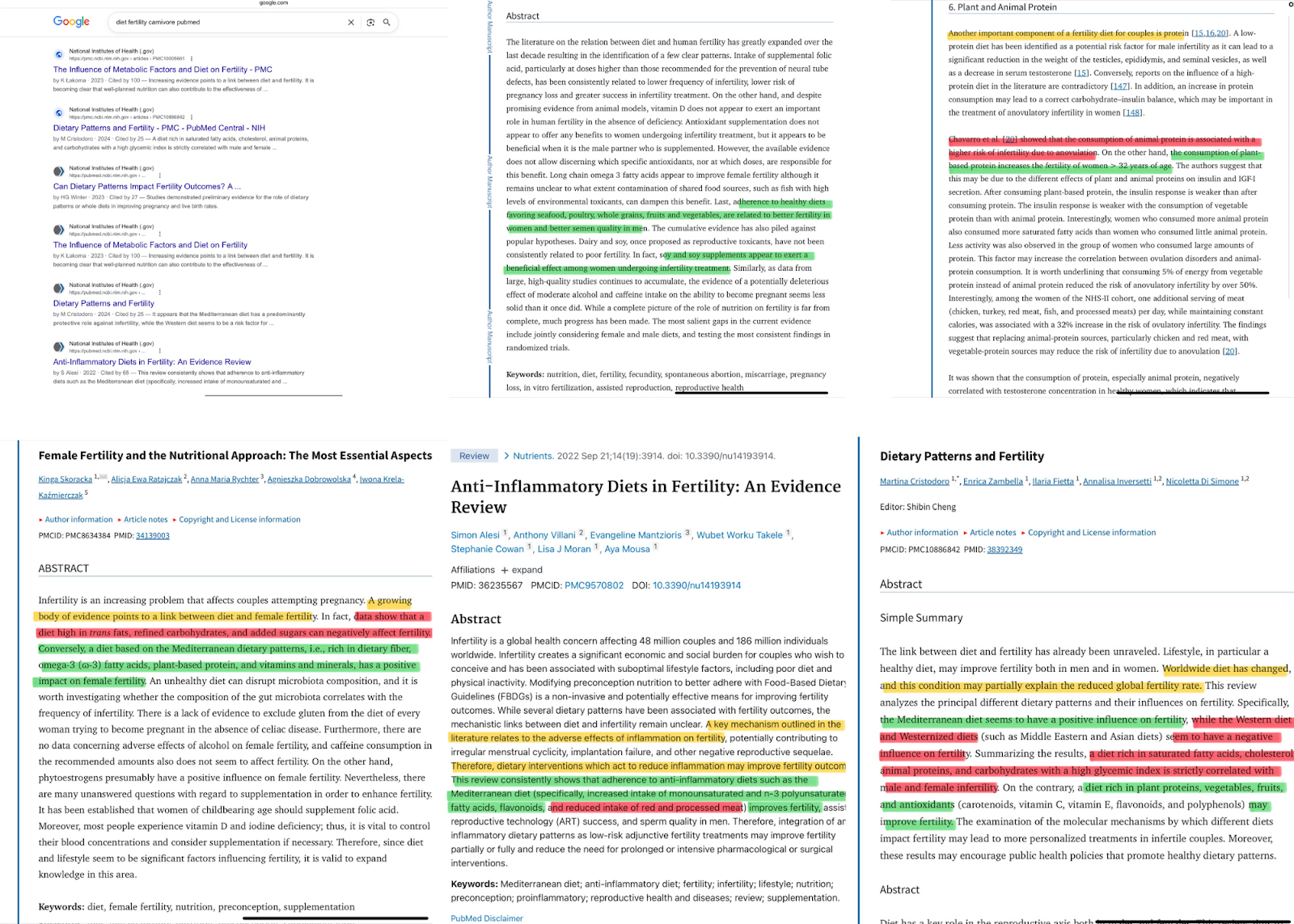

To conclude, it’s useful to visualise how social and popular media often distort the balance of available scientific evidence. A quick search for “carnivore diet fertility,” the kind of query a reader might make after encountering this story, yields several answers from Dr Kiltz and other carnivore promoters, lots of social media forums, and a single blog post challenging these popular claims.

However, simply adding the term “PubMed” to the same search produces an entirely different picture: a large number of peer-reviewed studies examining the relationship between dietary patterns and fertility. The snapshots below come from several of these papers, some of which are systematic reviews: studies that analyse and synthesise results from multiple investigations to identify consistent trends.

The aim of this visual comparison is not to present every study available, but to show how popular media can focus public attention on a narrow, highly promoted idea while overlooking the breadth and consistency of existing scientific evidence.

Social media further distorts this picture by amplifying confident voices that echo one another’s claims. A handful of personalities frequently cite each other across podcasts, blogs, and short-form videos, creating the illusion of a broad scientific consensus where there might be none. Algorithms reward repetition and emotional certainty, not accuracy or nuance.

This feedback loop obscures the substantial body of peer-reviewed evidence, and the many experts who do not share these views.

We have contacted The Sun and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Anecdotes gain particular influence when shared through social and popular media, where emotional resonance often outweighs scientific rigour. But without careful context, they can easily be misinterpreted. In this case, the implied message is twofold: 1) that a carnivore diet can support fertility and 2) that doctors do not tell women that diet matters. Let’s look at both claims in detail.

Claim 1: A carnivore diet can support fertility

Anecdotes alone cannot answer the question “can a carnivore diet support fertility?” because they lack the necessary context to separate cause from coincidence. In this case, we have no information about the woman’s medical history, underlying conditions, or other lifestyle changes she may have made, nor any way to know what would have happened had she not changed her diet. Without that background, it’s impossible to determine whether the outcome was linked to the diet itself, another factor, or simply chance.

Let’s examine what other evidence is used in the article to make and support this claim.

How is this claim presented in the article?

The article states that after “years avoiding meat,” the woman began eating “high-quality animal protein, eggs, butter and collagen-rich foods” and believed “the boost in nutrients and healthy fats played a key role.” She goes on to explain, “I watched a video of a doctor who recommended being on a carnivore diet to get pregnant.”

While this is presented as the turning point, the article does not name the doctor or provide any information about the existing evidence on the links between diet and fertility.

What evidence does the article provide?

The article relies on two main sources which are credited as supporting the validity of the claim:

- An unnamed doctor promoting a carnivore diet to become pregnant.

There are several doctors who promote the carnivore diet through their social media platforms. They represent a small but very visible minority among the medical community. For someone searching online for advice on using this diet to improve fertility, it is likely that they would come across the work of Dr Robert Kiltz, so it is reasonable to assume he may be the doctor being referenced in the article. Dr Robert Kiltz is a US-based obstetrician and gynaecologist who is board-certified in reproductive endocrinology. He has also written several books, in which he advocates for a “keto-carnivore diet” for fertility.

It is worth noting that in a recent video, Dr Kiltz questioned whether his own food choices could have led to recent, personal health issues (he mentions acute colitis), and concluded: “maybe my focus on only beef and carnivore is not going in the right direction.” Why does this matter? Because it highlights the importance of distinguishing between personal beliefs and peer-reviewed scientific research as a basis to guide dietary and health recommendations.

- A book: The Great Plant-Based Con by journalist Jayne Buxton, which argues that plant-based diets are harmful to health.

Again, this book is not peer-reviewed scientific work, and its conclusions contradict extensive evidence showing that well-planned plant-based diets are nutritionally adequate and associated with numerous health benefits (source).

This matters because popular media accounts can shape public understanding of what counts as “evidence.” When non-scientific materials and individual medical opinions are presented instead of peer-reviewed research, they can distort the public’s perception of scientific credibility.

The article also highlights a video by Steak and Butter Gal, a social media influencer frequently criticised by health professionals for spreading dietary misinformation and flawed reasoning which, if followed, could lead to health complications. The inclusion of this video further amplifies this one-sided narrative.

As a result, readers are left with a very skewed picture of what the science says about how diet might impact fertility – and there are a lot of studies looking precisely at those links, which the article fails to mention.

What evidence is not mentioned in the article?

The article omits decades of research examining the relationship between diet and fertility. Large-scale systematic reviews and meta-analyses published in journals such as Nutrients, Advances in Nutrition, or Biology (Basel) show that:

- Higher red and processed meat intake is linked with lower fertility rates and poorer embryo development (source, source).

- Diets rich in plant foods, fish, whole grains, and unsaturated fats, such as the Mediterranean diet, are associated with better fertility outcomes and improved metabolic and hormonal health (source, source, source).

- Including more plant-based sources of protein (such as lentils, beans and nuts) and fewer animal sources may improve fertility (source).

- Soy foods and dairy have been found to support fertility when consumed as part of balanced diets, contradicting popular hypotheses (source).

Dr Layne Norton addresses similar claims in the following video:

What about specific diets?

The keto diet shares some similarities with the carnivore diet mentioned in the article (both are high in fat and very low in carbohydrates), but unlike the carnivore diet, the keto diet typically includes a wider variety of foods, such as non-starchy vegetables, nuts, and dairy. Research surrounding keto diets and fertility is very limited. According to this review, it has mainly focused on obese and overweight women with PCOS, and the studies mentioned have a very small number of participants (27 and 12, respectively). The researchers also caution against the long-term use of this diet, “because it may also lead to deficiencies in certain important components and nutrients,” particularly during pregnancy.

This is a crucial point. It shows that while diet can indeed play a role in fertility, the issue is multifactorial. It is affected by underlying conditions, overall nutritional adequacy, and medical context. Anecdotes cannot answer the question “will this work for me?”, partly because we do not know the individual’s full health profile or whether other factors, such as PCOS, played a role. This underlines the importance of seeking guidance from qualified healthcare professionals when making dietary changes.

There is very limited data on carnivore diets themselves. Because such diets eliminate entire food groups and may pose nutritional risks, it would be ethically questionable to conduct trials particularly in populations trying to conceive.

Thus, the omission of this evidence leaves readers with the impression that a carnivore diet is a promising and potentially scientifically supported option, as it references at least one doctor who supports it. In reality, it is untested and contradicts existing data on the impact of different foods on fertility.

Bottom line

The emotional power of a personal story, combined with selective sourcing, makes the claim highly appealing.

But here’s the problem:

- It’s not about carnivore versus vegan. That framing attracts attention and clicks but oversimplifies nutrition science, which overwhelmingly supports balanced, diverse diets made up of whole foods.

- It’s an example of cherry-picking. The article only includes sources that support one side of the argument, ignoring substantial data to the contrary.

- It undermines scientific literacy. Understanding scientific evidence requires knowing how it is built. Research starts with a question. When results are reproduced and plausible biological mechanisms can explain why results occur, the evidence grows stronger.

Anecdotes, by contrast, sit at the bottom of the evidence hierarchy. They are valuable as starting points but cannot establish causation, because they don’t control for confounding factors or test biological mechanisms.

This leads us to the second implied claim and the main issue which comes from the framing of The Sun’s article: undermining trust in scientific evidence, and in health professionals.

Sensational headlines make for compelling reads. But their conclusions should be supported by data and evidence, otherwise the risk of inferring beyond individual circumstances is high.

An article published in The Sun on 25 October 2025 recounts the experience of a woman who, after several miscarriages, became pregnant with twins following a shift from a vegetarian or vegan diet to one centred on red meat and animal foods. The piece frames this change as a possible turning point in her fertility journey and suggests that a “carnivore” or high-animal-food diet played a decisive role.

This analysis does not question the woman’s personal experience. Instead, it offers a guide to reading articles like this one with a scientific lens: beyond the individual story, what evidence is presented to support the implied connection? What is left out, and how does this compare with what scientific research currently tells us about diet and fertility? The aim of this fact-check is to help readers assess how such narratives are constructed, what kinds of reasoning they invite, and where careful scrutiny is most needed.

Current scientific consensus shows that balanced, plant-rich dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet are linked to improved fertility outcomes, whereas high intakes of red and processed meat are associated with lower fertility. This is not about “carnivore versus vegan,” but about how we evaluate information. Sound evidence comes from repeated studies, transparent methods, and biological mechanisms that explain why patterns occur.

Articles like this one illustrate how selective framing can turn a single story into a persuasive but misleading narrative. Infertility concerns are profoundly sensitive and affect roughly one in six people worldwide. People experiencing repeated loss or difficulty conceiving are often searching for hope, which makes them particularly vulnerable to persuasive claims that promise control or certainty.

But when decisions are made on the basis of incomplete information, they can lead to restrictive or unbalanced diets that increase the risk of nutritional deficiencies and other health complications. This is why ensuring that health information is communicated accurately and in context is so important: it helps protect readers’ well-being and strengthens public trust in science and journalism alike.

Latest fact-checks, guides & opinion pieces

.svg)