Ultra-processed foods, plant-based meat and your health

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

The conversation around food processing has become front-page news, just as plant-based meat products have become a regular sight on our supermarket shelves.

With many people lacking an understanding of plant-based meat’s nutritional profile or how it is made – not to mention misleading headlines – it is easy to see why the debate around processing has led to confusion about the health profile of plant-based meat.

Despite generally having a good nutritional profile, and offering a simple swap for conventional processed meat, plant-based meat is often considered an ultra-processed food.

The subject of ultra-processing can often be complex. While most of the foods in the UPF category are undoubtedly unhealthy in excess, their categorisation is not based on nutritional criteria, and some of them have good nutritional profiles.

The system that gave us the term ultra-processed foods – a classification system called Nova – was developed to look at eating patterns on the population level and explore the food system shifts that have led to growing rates of chronic disease and diet-related ill health in several countries.

The Nova system suggests that a shift away from traditional home-cooked meals and towards convenient, cheap, mass-produced options (characterised as UPF) has played a role in driving negative health outcomes.

But this can’t explain the whole story – after all, a home-made cake may not be ultra-processed, but it is not advisable to eat every day.

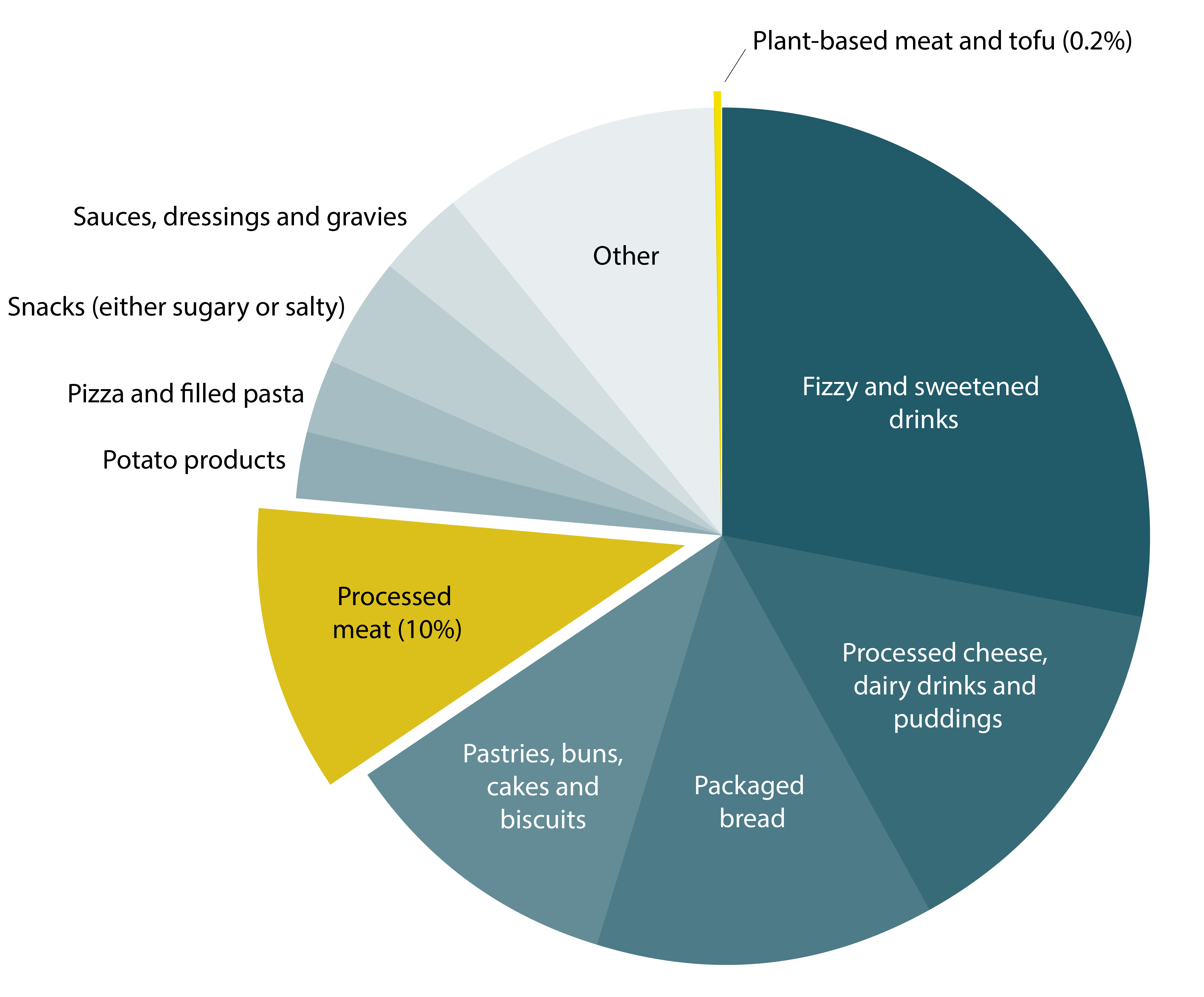

Foods falling into the UPF category also generally have poor nutritional profiles, are quick to buy and ready to eat, and are a much lower effort barrier to eating too much of them than if you had to make them from scratch. The foods making up the bulk of high-UPF diets in research tend to be high in salt, fat and sugar, and low in fibre – such as hot dogs, fizzy drinks, milkshakes, salty snacks, cakes and pastries.

It therefore makes sense that people with the highest proportion of their diets coming from these foods generally have worse outcomes, particularly when considering the UPF group by definition does not contain any fresh fruit and vegetables – an important part of any healthy, balanced diet.

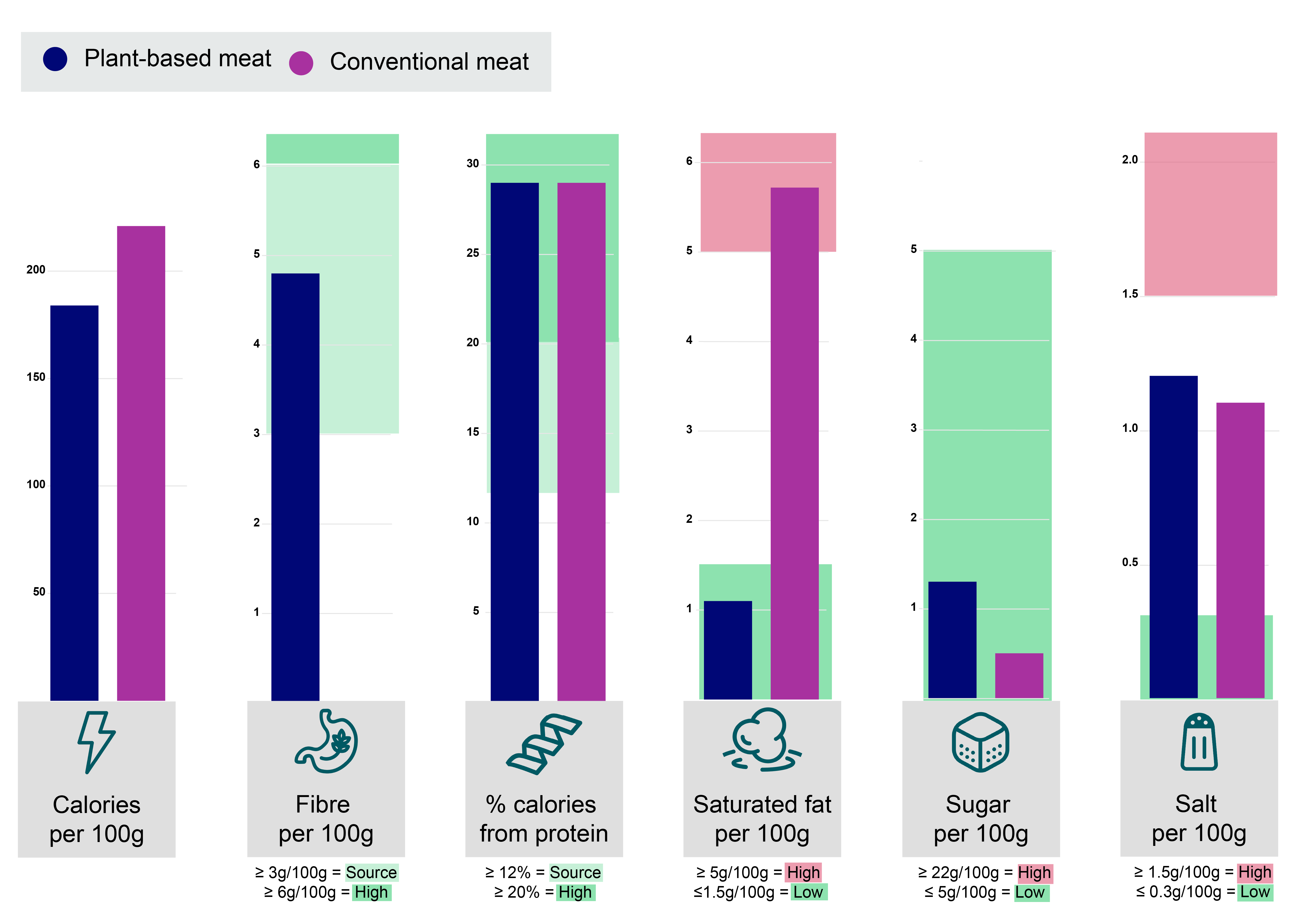

However, not all UPFs have a poor nutrient profile. Plant-based meat is a key example – generally being low in saturated fat and sugar, high in protein and a source of fibre.

Our guide, developed in collaboration with the Physicians Association for Nutrition International, aims to shine a light on the nuances and underlying evidence surrounding the complex topic of plant-based meat and the ultra-processing debate.

How plant-based meat can support healthier, more sustainable diets

Many European countries’ national dietary guidelines recommend the limiting of processed meat consumption, but the constant time pressures of modern lifestyles, coupled with an abundance of cheap, tasty products like bacon and ham, can make it hard to keep intake within recommended limits.

Plant-based meat offers a simple swap that is low in saturated fat (while processed meat is generally high) and offers a source of fibre (while conventional meat has none) while offering similar levels of protein.

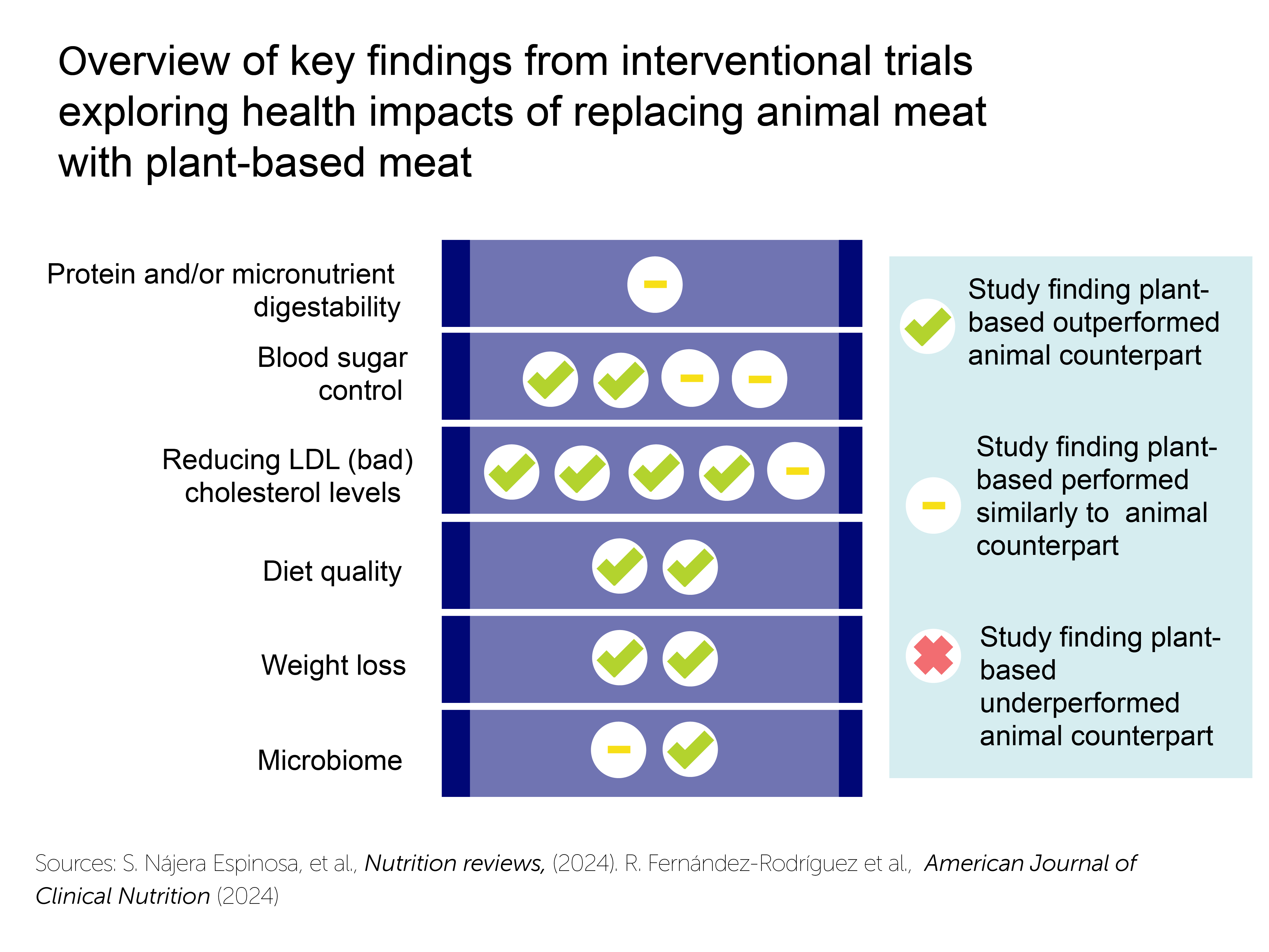

The evidence we have so far on plant-based meat is still at a relatively early stage, but what we do know is promising:

- It is well established that lower intakes of saturated fat are associated with reduced cardiovascular disease risk, and higher intakes of fibre are associated with several health benefits, including better weight management.

- The results of trials to date on the impact of swapping conventional meat with plant-based meat show benefits in line with these features of its nutritional profile – with the most consistent differences observed being reduction of LDL cholesterol, and modest weight loss in those above the recommended healthy weight. This is based on a systematic review and meta analysis of 7 randomised controlled trials comprising 369 adults.

- These findings are very different from studies looking at the impacts of diets high in UPF at the population level, which tend to find that high consumption of foods within the UPF category as a whole is associated with higher rates of obesity and cardiovascular disease.

In addition to this, there are several reasons why it is unlikely that available observational UPF research can be usefully applied to plant-based meat:

- Plant-based meat has a very different nutritional profile from the majority of foods in the UPF category. In particular, it is low in sugar and saturated fat, a source of fibre and high in protein.

- Plant-based meat makes up a vanishingly small percentage of calories eaten in the datasets used in most UPF research.

- The long-term nature of observational UPF studies means that the food diaries they are based on are often over 10 years old, use food frequency questionnaires that do not provide sufficient information for researchers to distinguish between plant-based meat and more traditional foods like tofu, and date back to a time when most modern plant-based meat options did not exist.

The best diet is one you can stick to

There is no single pathway to a healthy lifestyle, and different approaches clearly work better for different kinds of people. A key opportunity area for plant-based meat lies in its ease of adoption and ability to help reduce the current overconsumption of conventional processed meat, a subgroup of UPF with particularly strong associations with negative health outcomes when eaten in excess, observed in studies from Europe, the US and South Korea.

Plant-based meat is sometimes viewed as a niche food for those already following plant-rich diets like vegetarians, but its primary potential for public health lies in broader mainstream adoption.

It has the largest potential for the many people who enjoy meaty meals, eat less fibre and more processed meat than recommended, and don’t want to completely overhaul their diets, preferring options that fit within their existing daily routines and meals.

Increased availability of tasty, affordable, nutritious plant-based meat designed to appeal to these people could help improve diet quality and make plant-based foods more approachable and easier to prepare – currently a barrier to adoption for many people.

A study exploring the patterns in diet change of the ‘champion households’ for diet sustainability in the UK found two distinct patterns amongst the groups who most effectively reduced the greenhouse gas emissions of their diets. All of those successfully reducing emissions significantly reduced their intake of meat, but some switched meat for dairy, and some increased their intake of plant-based foods.

While both groups reduced the carbon footprint of their diet, only the plant-based increasing group saw co-benefits with health.

The meat to dairy group overall saw a decline in diet quality: there was no increase in consumption of vegetables or legumes, while foods that were increased varied significantly in nutritional profile. Dairy products saw by far the largest increases, followed by smaller increases in plant-based milk and fruit. Increases were also seen convenience food groups commonly associated with the UPF group: desserts, snacks and bakery.

Meanwhile, those taking the plant-based approach to increasing their intake reduced the environmental impact of their diets while also seeing improvements in diet quality. Vegetables, plant-based milk and fruit saw the largest increases in intake, followed by plant-based meat, legumes, nuts and seeds. In this group, unlike the meat to dairy group, common energy-dense foods such as confectionery, desserts, pre-prepared foods and bakery also fell.

This suggests that adoption of plant-based meat is generally more closely associated with the positive dietary shifts towards healthier and more sustainable diets than it is to other foods in the UPF group, and far from reinforcing the ‘status quo’ as is often suggested, they could make plant-rich diets more generally accessible and easier to stick to.

The role of fortified, high-protein plant-based foods in safeguarding food security

We know that in the shift towards healthier, more sustainable diets, we urgently need to eat more plant-based foods. But it is also important to remember that, at present, for most of the European population, animal-based foods are currently a primary source of several important nutrients like B12, zinc, iodine, calcium and long-chain omega 3s.

Several of these nutrients are not inherent to animal-based foods – and their presence and consistency are often the result of fortification added to animal feed and farming practices that boost the content of these nutrients.

One example is iodine. Not naturally found in dairy in high quantities, iodine is routinely added to cow feed and is also used as the base of some disinfectants used in milking, which consequently provide iodine content commonly found in dairy products.

B12 – often associated with animal products – is another example. B12 is only made by certain types of bacteria, and neither plants, animals nor fungi can naturally produce it. These other organisms must therefore get it either from diet or, in the case of ruminant animals, from symbiotic relationships with gut bacteria.

Fortified animal feed and veterinary supplementation are therefore the original source of much B12 in animal-based foods eaten in Europe, particularly in the case of the meat and eggs from birds and non-ruminants. In the wild, concentrations can also vary significantly between ruminant animals based on soil composition, so consistency is ensured in farmed ruminants through the routine provision of supplementation with cobalt to support these gut bacteria or direct supplementation with B12.

In contrast, consistency of fortification in plant-based meat and dairy is limited, and needs to be improved.

While fresh vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts and wholegrains contain a wide variety of health-promoting nutrients, plant foods also often contain compounds that make certain nutrients more difficult to digest than equivalents from animal or fungi-based foods – sometimes called ‘antinutrients’.

This is true for both micronutrients like calcium, zinc and iron, and also for protein. While these needs can usually be met by eating a larger volume of food, or by supplementing or planning diets more carefully, fortified plant-based foods with better bioavailability may make it easier for people less knowledgeable about nutrition, or people less able to eat larger volumes (eg older people) to get everything they need from their diet.

Certain processing approaches show promise in overcoming these challenges, and this is a key area where more research is needed.

Besides the environmental challenges associated with the current overconsumption of animal-sourced foods, our overreliance on meat and dairy for key nutrients at the population level also presents risks to food security. The ongoing bird flu epidemic is a prime example of this, underlining the importance of protein diversification in safeguarding affordable access to nutritious diets.

As the growing impacts of climate change on agriculture put increasing pressure on our food systems, the higher resource intensity of animal-source foods makes them susceptible to supply shocks and price increases. Nutrient-dense plant-based options that are tasty and affordable could therefore play a central role in a more resilient food system.

Without a nuanced approach to processing, however, these potential advantages may be neglected and the considerable opportunities offered by plant-based meat and other high-protein, fortified plant-based foods missed.

A more nuanced way to think about processing

A blanket message to “avoid all ultra-processed foods” risks hiding important differences between products, overlooking nutritionally useful options like fortified plant-based foods and confusing consumers, especially when time, cost and convenience all matter.

Instead, the focus should be on improving overall diet quality, and limiting UPFs that are clearly linked with harm when eaten in excess, such as sugary drinks, sweets, crisps, cakes, pastries and processed meat. Plant-based meat has clear potential to help achieve both of these goals.

Plant-based meat is not a cure-all, but nor is it simply “just another UPF”. When used thoughtfully, it can be a useful tool – alongside broader dietary shifts – in moving towards diets that are both healthier and more sustainable, without demanding an overnight transformation of how people eat.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)