Fibremaxxing explained: benefits, side effects, and how to do it right

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

Content creator GQ Jordan Nutrition recently shared a video highlighting a trend known as “fibremaxxing”, which reflects growing awareness of how important fibre is for digestion, gut health, and disease prevention.

But while the benefits of fibre are clear, she points out that increasing intake too quickly can sometimes cause uncomfortable side effects, and reminds her audience of the importance of also increasing water intake. This fact check looks at the reasons behind these effects, and what the science says about how to increase fibre intake.

Evidence shows that gradually increasing fibre intake, combined with sufficient hydration (2–3 litres of water daily), reduces these side effects and promotes better gut microbiota balance. Both soluble and insoluble fibre benefit from water: soluble fibre forms a gel-like consistency that slows digestion and feeds gut bacteria, while insoluble fibre absorbs water to add bulk and support regular bowel movements.

Nutrition trends can be difficult to navigate, and often oversimplify the science behind the hype. That’s why it’s essential to put nutrition tips into context: understanding not just what to eat, but how to do so safely, without losing sight of the bigger picture of a balanced diet.

When looking for recipes or diet advice online, follow trusted accounts from registered nutritionists or dietitians. They not only provide practical ideas but also explain the science behind them. @gqjordannutrition is one example of a creator who shares evidence-based nutrition in an accessible way.

Before looking at fibremaxxing, it helps to understand what fibre is and the role it plays in supporting digestion and long-term health.

What is fibre?

Dietary fibres refer to a form of carbohydrate found in plant-based foods that we consume, but do not get digested within the small intestine. Instead, they travel to the large intestine, where they are either completely or partly fermented by gut bacteria. Fibre is made up of carbohydrates called polysaccharides and resistant oligosaccharides (ROS).

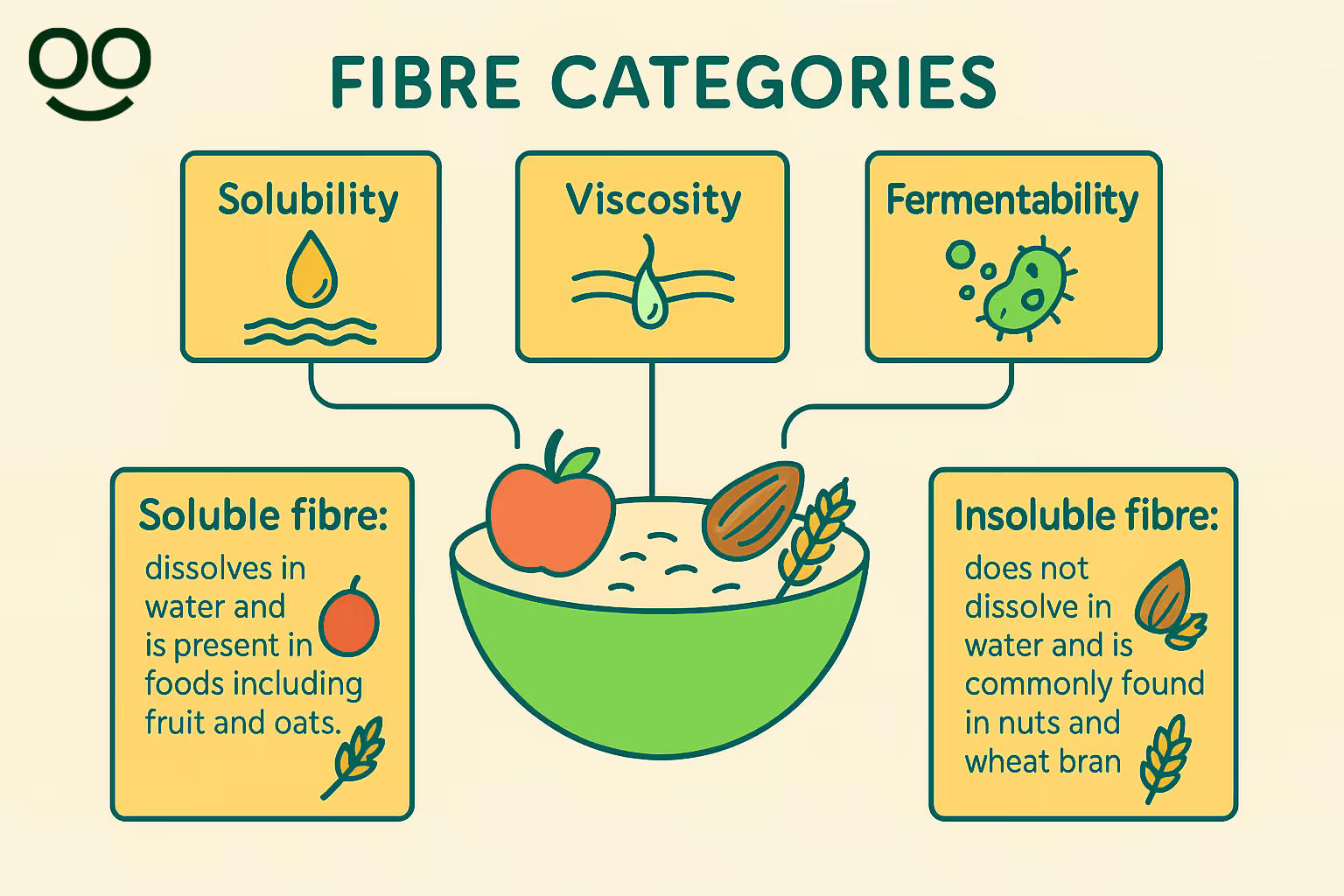

Emerging evidence indicates that fibre should be grouped based on its physical features: its ability to dissolve in water (solubility), its thickness (viscosity) and how easily it can be broken down by bacteria (fermentability). Some commonly known terms are described below:

- Soluble fibre: dissolves in water and is present in foods including fruit and oats.

- Insoluble fibre: does not dissolve in water and is commonly found in nuts and wheat bran (source).

Why increasing fibre intake matters

Fibre is a crucial but often overlooked nutrient, especially in a culture where protein and other macronutrients tend to get most of the attention. Current guidelines state adults should aim for 30g of fibre a day (source). However, recent data indicates that adults are not hitting this, with average fibre intake for adults in the UK being 18g, just 60% of what they should be.

Fibre is incredibly important for a number of reasons. Fibre travels through the digestive system largely intact until it reaches the colon, where it becomes food for the bacteria that makes up our gut microbiome, increasing the diversity of our gut bacteria. Research reviewing 35 studies discovered links between fibre from whole grains and larger volumes of ‘good’ bacteria (e.g. Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus), and lower amounts of bacteria which can have adverse side effects (e.g. E. coli) (source). When fibre is fermented by gut bacteria, it produces compounds known as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), whose key role has been established as supporting our general health. Increasing dietary fibre intake therefore can enhance our immune function (source). For example, one SCFA (butyrate) has the particular benefit of regulating sleep and mood, and reducing inflammation (source).

A diet high in fibre has also been linked to a lower risk of developing several diseases. One study (source) revealed that fibre was associated with a 24% lower risk of heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and colon cancer. Wholegrain fibre specifically (in foods like quinoa, wholegrain bread and oats) has a particularly protective effect.

Can increasing fibre cause digestive issues?

In response to growing evidence on fibre’s role in supporting digestion and overall health, the trend of ‘fibremaxxing’ has emerged on social media. The term refers to deliberately maximising fibre intake, often by increasing it rapidly. However, consuming a large amount of fibre too fast could cause some uncomfortable digestive effects, including cramps, gas, bloating, and possibly diarrhoea (source).

Fibre influences health through different pathways, and one process is fermentation in the gut. In essence, any undigested carbohydrate that reaches the colon is fermented by gut bacteria to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), along with gases. Therefore, one side effect of fibre ingestion and subsequent fermentation may be the production of gases such as carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and methane. These gases can produce unwanted discomfort, bloating and flatulence for many.

Different fibre types (e.g. soluble and insoluble) can have different fermentability which influences gas production and therefore individual symptoms (source). For example, resistant starch is a form of soluble fibre that is highly fermentable in the gut, and gets digested by ‘good’ bacteria to produce SCFAs. Examples of foods that resistant starch is naturally present in are bananas, grains, pulses and potatoes (source).

It is important to note, that for individuals with an existing digestive condition, such as Irritable Bowel Disease (IBS), caution should be exerted when introducing greater amounts of fibre into their diet, as these conditions can restrict your fibre intake (source). If this is the case, consult a dietician before choosing to implement more fibre in your diet (source, source).

Should I gradually increase my fibre intake?

GQ Jordan states that “things can start to go wrong when people go from 0-100 too quickly” and that our “gut needs time to adjust.” Jordan’s recommendation to increase fibre intake gradually is consistent with established dietary guidelines. If you are planning to boost your fibre consumption, it’s best to do so slowly. This helps prevent digestive discomfort, such as bloating and gas, and gives your gut time to adapt to the higher levels of fibre (source).

To gradually increase fibre, consider some of the following as more gradual, sustainable changes:

Can water help?

One of the most important points often left out of social media posts is as Jordan points out, that “you need to increase your water intake as you increase your fibre. Otherwise it can back you up.” This is true: both soluble and insoluble fibre need water to work effectively. Ensuring that you drink enough fluids regularly helps prevent constipation (source).

Jordan suggests that individuals increasing their fibre intake should aim for “two and a half to three litres a day.” This advice is supported by scientific evidence: in a clinical study where participants doubled their fibre intake, those who drank two litres of water per day were less likely to experience temporary digestive issues such as bloating and discomfort, and their gut bacteria shifted in a healthier direction (source).

In short: pairing fibre with sufficient water is essential to get the full digestive and nutritional benefits (source).

Final take away

Fibremaxxing, in the context of a balanced diet, is one of the few nutrition trends circulating online that is actually backed by strong scientific evidence: most of us need more fibre, and increasing intake supports digestion, immunity, and long-term health. But as with everything in nutrition, context matters. If fibre is added too quickly or without enough water, discomfort can follow. The solution isn’t to ditch fibre altogether, but to make changes gradually, and if problems persist, to seek guidance from a registered nutritionist or dietitian.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources

Check out our guide on increasing fibre intake.

British Dietetic Association (2025). “Fibre”

Smith, E. (2025). “Should We All Be Fibremaxxing?”

British Medical Journal (2019). “Eating more fibre linked to reduced risk of non-communicable diseases and death, review finds”

Eswaran, S. et al. (2013). “Fibre and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders”

Jarai, M. (ZOE) (2025). “Should I try a high fibre diet?”

Tangestani, H. et al. (2020). “Whole Grains, Dietary Fibers and the Human Gut Microbiota”

Gonçalves, G. V.R. et al. (2022). “Short-term intestinal effects of water intake in fibre supplementation in healthy, low-habitual fibre consumers: a phase 2 clinical trial”

Hervik, A.K. & Svihus, B. (2019). “The Role of Fiber in Energy Balance”

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)