.avif)

Five easy nutritionist-approved ways to boost your fibre intake every day

How much fibre do we need?

For adults, the government recommendation is 30 g per day. Children need different amounts depending on their age. There aren’t set guidelines for under-twos, but once babies start solids (from about 6 months), their diet should include some fibre-rich foods.

Introducing fibre gradually

If your current diet is low in fibre, suddenly eating a lot more can leave you feeling bloated. A slower, more steady increase is best, this gives your digestive system and the bacteria that live there, time to adjust.

Can you have too much?

Yes. While fibre is important, going overboard can cause bloating, constipation, diarrhoea, and sometimes even dehydration. It is important to drink enough liquid on a higher fibre diet as fibre absorbs water (6-8 large glasses of fluid a day).

Looking to add more fibre to your meals?

The British Nutrition Foundation provides some tips on how you can achieve this:

- Start with breakfast. A bowl of porridge, bran flakes, or wholewheat biscuits is a fibre-friendly way to kick off the morning. You can even boost this further by topping your cereal or yoghurt with fresh or dried fruit, nuts and seeds.

- Rethink your bread. If you normally opt for white loaves, try a “half and half” option made with both white and wholemeal flour. You can gradually build up to wholemeal bread.

- Keep the skins on. Baked potatoes, wedges or boiled new potatoes have higher fibre with their skins left on.

- Pile on the veg. Add vegetables to stews, curries, sauces or serve them as sides, or a snack, a simple trick to help everyone eat more greens.

- Mix in pulses. Beans, lentils and chickpeas slip easily into salads, stews and curries, boosting fibre without much effort. You can use dried or canned.

For people with IBS, fibre can be a bit of a balancing act. Some high-fibre foods, especially cereals and grains, may trigger bloating or discomfort, but not everyone reacts the same way. If this sounds familiar, you might find it easier to get more of your fibre from fruits and vegetables instead.

There’s no single diet or treatment that works for everyone with IBS. That’s why it’s important to talk to your GP. They may recommend keeping a food diary to help identify your personal triggers, while also ensuring you’re still getting enough fibre to support your health.

Eggs versus oats, what’s better for your heart health?

Claim 3: Eating “10 eggs a day is fine.”

Fact-check: The title of the video, “Why 10 Eggs a Day is Fine”, is a very bold statement, likely designed to grab attention. Inchauspé does not clearly provide evidence for this claim in the video.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 66 randomised clinical trials concluded that one egg per day can be considered safe and a useful recommendation for the prevention of cardiovascular disease; however, consuming more than one egg per day can significantly elevate blood total and LDL-cholesterol levels.

Final take away

Be wary of bold claims that exaggerate study results to grab your attention and possibly aim to sell you a product. Claims that strongly suggest eating one type of food over another when it comes to whole foods should be considered carefully.

Nutrition content often sets foods up against each other. This framing is usually used to promote a particular dietary pattern as superior, rather than reflecting the evidence base. In reality, whole foods like eggs and oats are not simple substitutes, and both can play different roles in a balanced diet.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Claim 2: Replacing oats with eggs for breakfast lowers inflammation.

Fact-check: This is overstated, as the study Jessie cites did not show eggs were universally better than oats.

In her video, Inchauspé cites a study that, she claims, shows eggs are better for you than oats because they lower inflammation in people with diabetes. She claims the study shows that when people replace their oats with eggs, the inflammation in their bloodstream goes down. In this study, the participants were given a calorie-matched breakfast with either one egg/day or 40 g of oatmeal for 5 weeks, then had a 3-week break, then consumed the alternate breakfast for 5 weeks.

What did the study actually say?

When we look at the study, Inchauspé is missing out on several key results to give the full picture. After consuming the egg and oats breakfasts, the two groups had no significant differences in weight, fat, blood pressure, lipids, HbA1c, insulin, and C-reactive protein, which is the main inflammatory marker. They did, however, find that one inflammatory marker was lower in the egg group, a marker called TNF-alpha. However, as they didn’t measure this marker at the start of the study, it’s possible that both eggs and oats actually decreased TNF-alpha, and it just decreased further in the eggs group.

The participants of the study were served one egg with vegetables and bread or tortillas. It is a well-known fact that vegetables are good for many reasons. Therefore, the addition of those in your breakfast is always a good idea whether it is with eggs or oatmeal, granted that could be considered strange. Secondly, the participants were given bread or tortillas, meaning they were consuming carbs with their eggs. Hence, the argument that eating carbohydrates is a bad idea doesn’t hold.

The study authors suggest that consuming 1 egg if you have type 2 diabetes could be beneficial when compared to oatmeal. Type 2 diabetes is a complex chronic disease, and what applies to this group may not necessarily apply to another group, such as a generally healthy population. Making recommendations based on one study like this doesn’t apply to the general population.

Claim 1: “Eggs are better for you than having oats and juice in the morning for your heart.”

In her video, Inchauspé explains that we need to reduce sugar to improve heart health. This leads into Jessie saying “[...] so instead of having orange juice and oats in the morning, which are carbs and turn to glucose in the body…have eggs.”

Simplifying oats into a food that simply turns to glucose in the bloodstream ignores the fact that they are complex carbohydrates, with plenty of fibre and are associated with several health benefits. Furthermore, categorical statements such as have food X but not Y are usually exaggerated.

It is important to make a distinction between naturally occurring sugar and added sugar. Naturally occurring sugars are those found naturally in foods such as milk, fruits, and vegetables. Together with those sugars, these foods contain vitamins, minerals, and fibre, making them important components of our diet. Added sugars are, like the name suggests, added to food products. Added sugars, or ‘free sugars’, are commonly found in biscuits, chocolate, flavoured yoghurts, breakfast cereals and fizzy drinks.

.avif)

On average, the UK population consumes too much added sugar. Therefore, the advice to reduce the consumption of foods high in free sugars isn’t necessarily ‘wrong’. However, the sugar found in oats is not the same free sugars found in a fizzy drink. Oats are primarily complex carbohydrates - starch, which digests more slowly than non-complex carbohydrates such as white bread, meaning they leave you feeling fuller for longer. Oats also contain fibre, especially beta-glucan, which has been consistently shown to reduce cholesterol. Consuming oats is widely recognised as health-promoting; their health benefits include regulating blood sugar, promoting satiety, lowering LDL-cholesterol levels, and enhancing immune function.

Fruit juice could be substituted for whole fruit to make breakfast healthier. This study shows that sugar-sweetened beverages and juices increase pro-inflammatory markers, increase triglyceride and high-density lipoprotein ratio, while whole fruits showed lower proinflammatory markers, lower blood lipids.

Always be wary of claims that don’t clearly cite their evidence.

On the 25th of June, Jessie Inchauspé, also known as the Glucose Goddess, posted a video with the title ‘Why 10 Eggs a Day is Fine: The Science of Cholesterol & Heart Health’.

In this fact-check, we break down some of the key claims Jessie Inchauspé makes in the video.

Most evidence does not suggest that eggs are unhealthy or bad for cholesterol and heart health. However, there may be an upper limit to the number of eggs considered healthy. The narrative that porridge and juice are bad breakfast foods is also unsupported by evidence.

The advice around eggs is confusing, with a lot of conflicting information. Read on for a clear breakdown of these new claims.

Fibremaxxing explained: benefits, side effects, and how to do it right

Before looking at fibremaxxing, it helps to understand what fibre is and the role it plays in supporting digestion and long-term health.

What is fibre?

Dietary fibres refer to a form of carbohydrate found in plant-based foods that we consume, but do not get digested within the small intestine. Instead, they travel to the large intestine, where they are either completely or partly fermented by gut bacteria. Fibre is made up of carbohydrates called polysaccharides and resistant oligosaccharides (ROS).

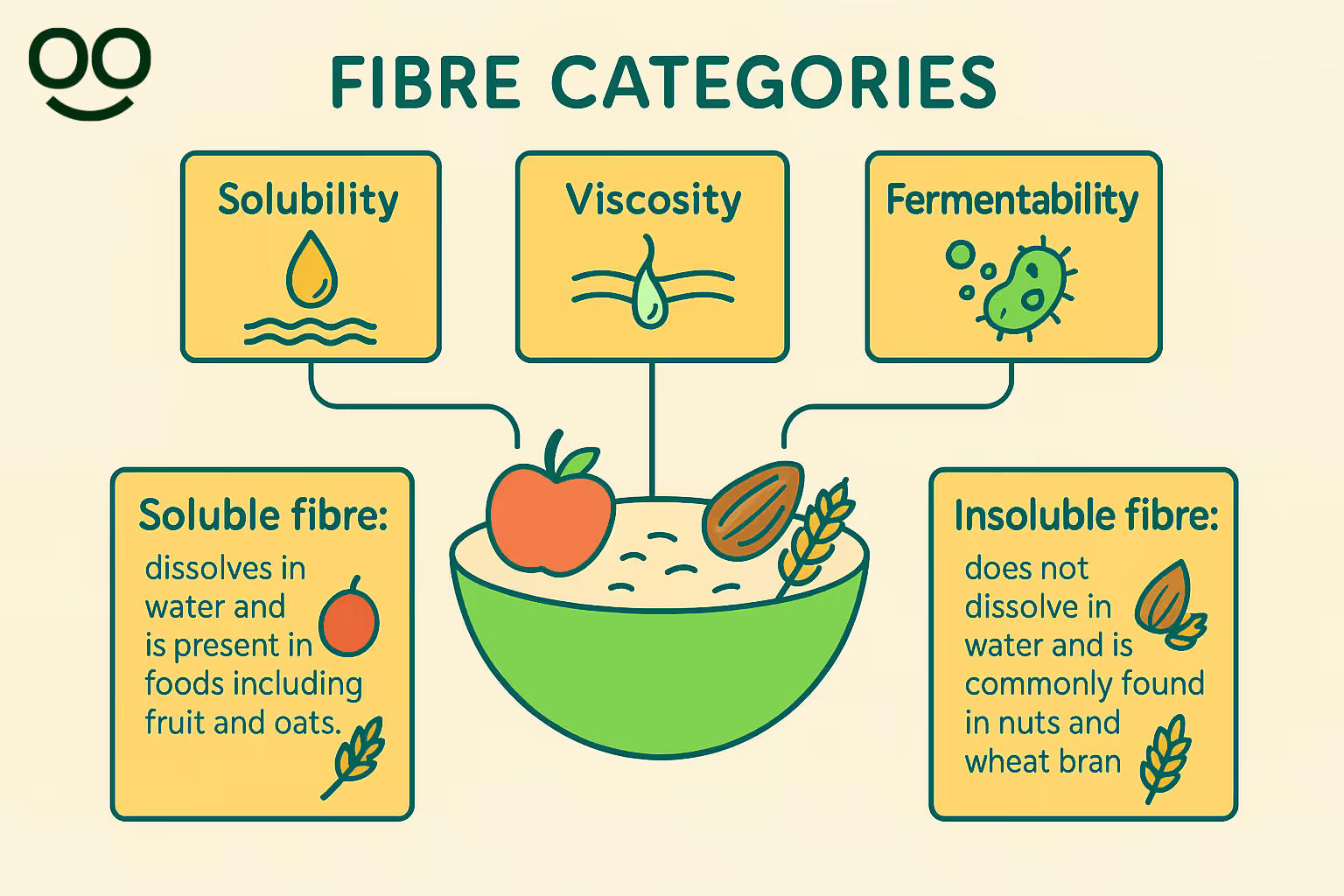

Emerging evidence indicates that fibre should be grouped based on its physical features: its ability to dissolve in water (solubility), its thickness (viscosity) and how easily it can be broken down by bacteria (fermentability). Some commonly known terms are described below:

- Soluble fibre: dissolves in water and is present in foods including fruit and oats.

- Insoluble fibre: does not dissolve in water and is commonly found in nuts and wheat bran (source).

Why increasing fibre intake matters

Fibre is a crucial but often overlooked nutrient, especially in a culture where protein and other macronutrients tend to get most of the attention. Current guidelines state adults should aim for 30g of fibre a day (source). However, recent data indicates that adults are not hitting this, with average fibre intake for adults in the UK being 18g, just 60% of what they should be.

Fibre is incredibly important for a number of reasons. Fibre travels through the digestive system largely intact until it reaches the colon, where it becomes food for the bacteria that makes up our gut microbiome, increasing the diversity of our gut bacteria. Research reviewing 35 studies discovered links between fibre from whole grains and larger volumes of ‘good’ bacteria (e.g. Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus), and lower amounts of bacteria which can have adverse side effects (e.g. E. coli) (source). When fibre is fermented by gut bacteria, it produces compounds known as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), whose key role has been established as supporting our general health. Increasing dietary fibre intake therefore can enhance our immune function (source). For example, one SCFA (butyrate) has the particular benefit of regulating sleep and mood, and reducing inflammation (source).

A diet high in fibre has also been linked to a lower risk of developing several diseases. One study (source) revealed that fibre was associated with a 24% lower risk of heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and colon cancer. Wholegrain fibre specifically (in foods like quinoa, wholegrain bread and oats) has a particularly protective effect.

Can increasing fibre cause digestive issues?

In response to growing evidence on fibre’s role in supporting digestion and overall health, the trend of ‘fibremaxxing’ has emerged on social media. The term refers to deliberately maximising fibre intake, often by increasing it rapidly. However, consuming a large amount of fibre too fast could cause some uncomfortable digestive effects, including cramps, gas, bloating, and possibly diarrhoea (source).

Fibre influences health through different pathways, and one process is fermentation in the gut. In essence, any undigested carbohydrate that reaches the colon is fermented by gut bacteria to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), along with gases. Therefore, one side effect of fibre ingestion and subsequent fermentation may be the production of gases such as carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and methane. These gases can produce unwanted discomfort, bloating and flatulence for many.

Different fibre types (e.g. soluble and insoluble) can have different fermentability which influences gas production and therefore individual symptoms (source). For example, resistant starch is a form of soluble fibre that is highly fermentable in the gut, and gets digested by ‘good’ bacteria to produce SCFAs. Examples of foods that resistant starch is naturally present in are bananas, grains, pulses and potatoes (source).

It is important to note, that for individuals with an existing digestive condition, such as Irritable Bowel Disease (IBS), caution should be exerted when introducing greater amounts of fibre into their diet, as these conditions can restrict your fibre intake (source). If this is the case, consult a dietician before choosing to implement more fibre in your diet (source, source).

Should I gradually increase my fibre intake?

GQ Jordan states that “things can start to go wrong when people go from 0-100 too quickly” and that our “gut needs time to adjust.” Jordan’s recommendation to increase fibre intake gradually is consistent with established dietary guidelines. If you are planning to boost your fibre consumption, it’s best to do so slowly. This helps prevent digestive discomfort, such as bloating and gas, and gives your gut time to adapt to the higher levels of fibre (source).

To gradually increase fibre, consider some of the following as more gradual, sustainable changes:

Can water help?

One of the most important points often left out of social media posts is as Jordan points out, that “you need to increase your water intake as you increase your fibre. Otherwise it can back you up.” This is true: both soluble and insoluble fibre need water to work effectively. Ensuring that you drink enough fluids regularly helps prevent constipation (source).

Jordan suggests that individuals increasing their fibre intake should aim for “two and a half to three litres a day.” This advice is supported by scientific evidence: in a clinical study where participants doubled their fibre intake, those who drank two litres of water per day were less likely to experience temporary digestive issues such as bloating and discomfort, and their gut bacteria shifted in a healthier direction (source).

In short: pairing fibre with sufficient water is essential to get the full digestive and nutritional benefits (source).

Final take away

Fibremaxxing, in the context of a balanced diet, is one of the few nutrition trends circulating online that is actually backed by strong scientific evidence: most of us need more fibre, and increasing intake supports digestion, immunity, and long-term health. But as with everything in nutrition, context matters. If fibre is added too quickly or without enough water, discomfort can follow. The solution isn’t to ditch fibre altogether, but to make changes gradually, and if problems persist, to seek guidance from a registered nutritionist or dietitian.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

When looking for recipes or diet advice online, follow trusted accounts from registered nutritionists or dietitians. They not only provide practical ideas but also explain the science behind them. @gqjordannutrition is one example of a creator who shares evidence-based nutrition in an accessible way.

Content creator GQ Jordan Nutrition recently shared a video highlighting a trend known as “fibremaxxing”, which reflects growing awareness of how important fibre is for digestion, gut health, and disease prevention.

But while the benefits of fibre are clear, she points out that increasing intake too quickly can sometimes cause uncomfortable side effects, and reminds her audience of the importance of also increasing water intake. This fact check looks at the reasons behind these effects, and what the science says about how to increase fibre intake.

Evidence shows that gradually increasing fibre intake, combined with sufficient hydration (2–3 litres of water daily), reduces these side effects and promotes better gut microbiota balance. Both soluble and insoluble fibre benefit from water: soluble fibre forms a gel-like consistency that slows digestion and feeds gut bacteria, while insoluble fibre absorbs water to add bulk and support regular bowel movements.

Nutrition trends can be difficult to navigate, and often oversimplify the science behind the hype. That’s why it’s essential to put nutrition tips into context: understanding not just what to eat, but how to do so safely, without losing sight of the bigger picture of a balanced diet.

The surprising reality about blood sugar spikes (it’s not what you think)

A key issue with health advice on social media is that we don’t always know who the audience is. As Kate also points out,

“People who don't have glycaemic control issues don't necessarily have to be worrying about blood glucose spikes as their pancreas can manage it effectively, and perhaps this is the audience Freelee is trying to target with this advice. However if this is the case, these individuals aren't worrying about their HbA1c anyway. The people who do have to worry might be the people who would be listening to this messaging, aka people with type 2 diabetes or insulin resistance, and thus this messaging is harmful for their glycaemic control.”

This highlights the potential danger of extreme-sounding claims: the people most likely to take them seriously might be the ones for whom the advice may be most harmful.

Rather than hyperfixating on individual glucose readings, the evidence supports a more balanced approach: eating a variety of whole, minimally processed foods, including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, protein sources, and healthy fats. This supports stable energy, reduces risk of disease, and avoids the pitfalls of extreme or overly simplistic dietary advice.

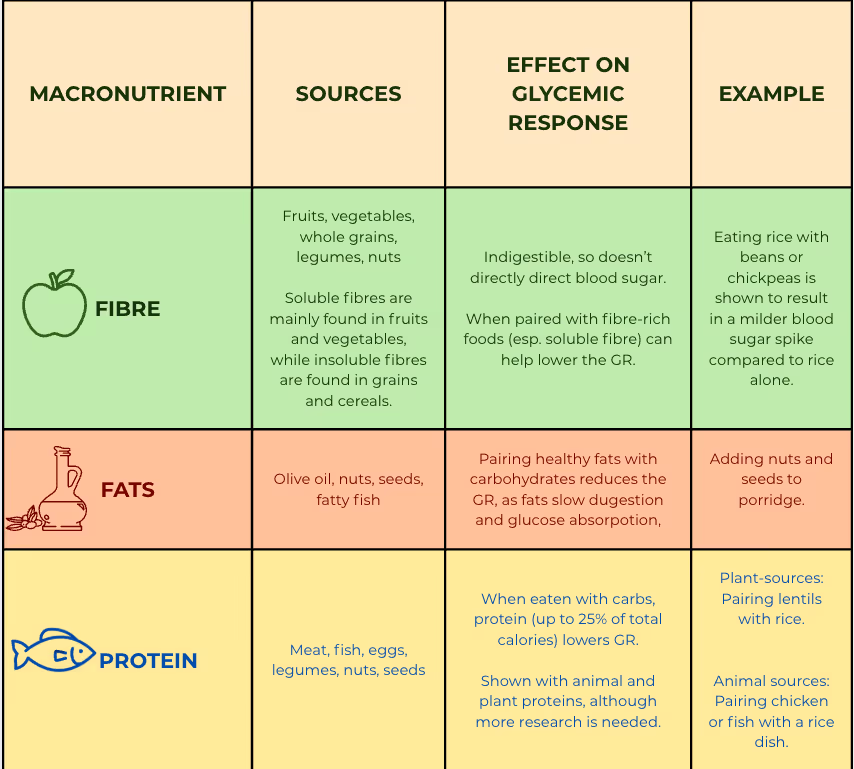

Combining foods to modulate glycemic response (GR)

The glycemic impact of a food can change when eaten alongside other nutrients. For example, pairing carbohydrate-rich foods with those high in fibre, fat, or protein slows gastric emptying, delaying carbohydrate absorption and reducing the GR (source, source). Carbohydrates are the body’s main source of glucose, typically digesting within 1–2 hours. Those high in fibre, like whole grains, beans, and lentils, digest more slowly and help moderate glucose absorption. Protein, on the other hand, has little effect on blood sugar, as it doesn’t convert directly to glucose. It digests more slowly than carbs, usually over 3–4 hours. Fat slows digestion overall, delaying the rise in glucose after a meal. While moderate fat intake has minimal impact, excessive amounts may contribute to insulin resistance and prolonged elevated blood sugar.

Eating balanced meals and snacks throughout the day, while combining high-fibre carbs, lean protein, and healthy fats, can help maintain steady glucose levels, supporting energy and satiety (source).

Claim 3: Fruit sugar is metabolically “clean”

Fact-check: The claim that fruit sugar is uniquely “clean” oversimplifies how the body processes sugars, especially when it comes to glycation and metabolic health.

Glycation happens when certain sugars stick to proteins, fats, or DNA in the body, forming harmful compounds called Advanced Glycation Endproducts (AGEs). These AGEs can damage how proteins work (source). Eating too much sugar, and especially fructose from sources like fruit, may speed this process up, since fructose is more reactive than glucose (source). Studies show that fructose causes glycation much faster than glucose in lab tests (source, source). Over time, high levels of AGEs can disrupt fat metabolism, trigger inflammation, and damage the body’s energy systems, all of which raise the risk of metabolic diseases (source).

It is worth noting that FreeLee’s focus on raw, unprocessed fruit has some benefits for glucose control.

Food processing breaks down natural structures, making nutrients more accessible for digestion and increasing blood sugar responses. Therefore, choosing whole, unprocessed foods over refined alternatives is recommended to help stabilise glucose levels (source). While eating unprocessed foods and ensuring you are eating enough plants is important, the NHS recommendations currently suggest that at least 5 portions of fruit and vegetables a day is optimal.

Final take away

In her response to us, Freelee supported her arguments with numerous scientific sources. However, several of these are drawn from clinical contexts that don’t necessarily apply to the general population, such as studies on type 1 diabetes or complications like gastroparesis. Registered Dietitian Leah McGrath notes that others are outdated, with some more than a decade old despite frequent updates in diabetes research and guidelines. In some cases, the sources are overgeneralised or taken out of context. For example, a study on kiwi fruit (a low-glycaemic fruit) is used to support claims about all fruit, and a paper on fructose metabolism is cited without acknowledging that it also describes adverse effects such as insulin resistance. This pattern of selecting sources that appear supportive while overlooking limitations is common in nutrition messaging on social media and can end up undermining nutrition literacy.

Nutrition and metabolism are (sometimes frustratingly) complex and nuanced, and when those nuances are lost, it can leave us more confused. This is how we end up with some influencers urging us to do everything possible to “flatten glucose spikes” (often while promoting supplements), while others swing the other way, encouraging diets made up largely of fruit and glucose.

It’s understandable that this mix of advice can feel overwhelming. Ultimately, the overemphasis on glucose itself is not helpful. Hyper-focusing on it can demonise certain foods, lead to unnecessary restriction, and create a stressful relationship with eating, when food should be both nourishing and enjoyable.

The encouraging part is that the reality is less extreme than the narratives that are found circulating online, and there are simple, evidence-based habits that support overall health, and which dietitian Kate Hilton summarises below, in the final Expert Weigh-In.

Disclaimer

This fact check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

We also recognise that there are many other aspects of glucose metabolism, diet, and health that could continue and deepen this conversation. The purpose here is to clarify the main points of the claim and to contextualise the way in which social media conversations sometimes use scientific concepts in ways that can oversimplify or mislead.

For readers interested in learning more, we recommend following accounts by specialists who cover these topics in greater depth, such as Dr Nicola Guess or Kate Hilton at Diets Debunked.

We would also like to thank Freelee for taking the time to share her clarifications with us.

Claim 2: Fat-containing meals “may blunt the early rise [in glucose] but cause a glucose drag (a delayed and prolonged elevation), leading to greater overall exposure” to glucose.

Fact-check: When asked to clarify her position on the benefits of sharper spikes, Freelee further discussed the notion of “glucose drag”. However, the claim that fat and protein cause “glucose drag” overlooks their key role in moderating blood sugar responses. Pairing carbohydrates with fibre, fat, or protein slows digestion and flattens the glycaemic response, something consistently shown to support long-term glucose control.

Freelee supports her argument by making a distinction between glucose spikes and ‘the area under the curve (AUC)’. In Freelee’s words, “AUC represents the total glucose exposure over time, and it is this exposure that correlates most directly with HbA1c, the clinical marker of three-month average glucose. In other words, larger or prolonged AUC translates into higher HbA1c values, whereas brief, contained spikes with rapid clearance do not.” From this, she concludes on the benefits of fruit-based meals, arguing that these produce a sharp but short-lived rise in glucose, which is followed by a rapid return to baseline. These are complex issues, which dietitian Kate Hilton helps us to unpack and contextualise:

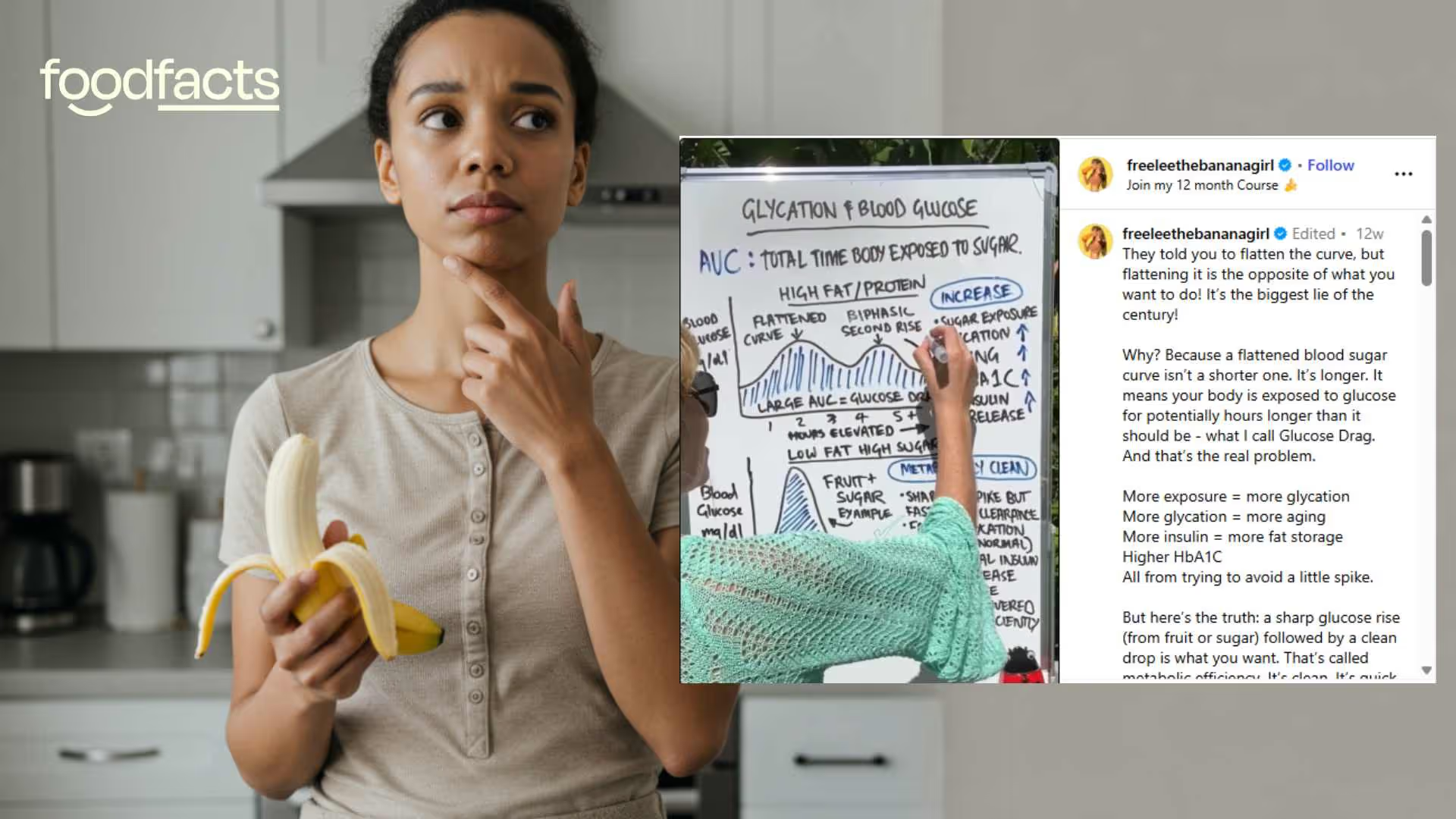

Claim 1: “You want to spike your blood glucose.”

Fact-check: The wording here is what might be problematic: saying that “you want to spike your blood glucose” or “aim for glucose spikes” implies that these spikes are beneficial, and that we should then deliberately try to raise our blood sugar. When we reached out to Freelee for comment, she provided an important clarification, explaining that “when [she speaks] about “aiming for glucose spikes,” [she’s not] suggesting uncontrolled hyperglycemia.” Rather, she is referring to the normal, physiological rise in blood glucose that follows a meal. Freelee describes this rise as “normal, necessary, and beneficial.” Let’s break down what happens to your blood sugar when you eat: what’s normal, and what’s not.

Fluctuations are normal…

Blood sugar levels (also known as glucose levels) indicate the amount of glucose present in the bloodstream, after the body processes carbohydrates from food and beverages daily. It is normal for these levels to rise and fall throughout the day, although individuals with diabetes experience more frequent and heightened fluctuations. It is important not to demonise glucose, a narrative often circulating online, as glucose is a vital energy source for your brain, muscles and tissues (source).

Hypoglycaemia, or low blood sugar, occurs when blood glucose levels fall below 4mmol/litre. This is typically rare in individuals who do not have diabetes (source). Hyperglycaemia, or high blood sugar can also take place when blood glucose levels are higher than 7mmol/litre, usually impacting individuals with diabetes (source).

Some experts have criticised influencers like the Glucose Goddess for pathologising a completely normal phenomenon: glucose fluctuations. For example, Dr Gary McGowan has spoken widely about this topic in several videos, such as this one.

…but that doesn’t mean that glucose spikes are beneficial

For individuals without diabetes, there’s no need to micromanage blood sugar spikes or rely on strict eating rules to maintain blood sugar below a set ‘limit’.

But just because flattening every glucose rise isn’t necessary for most people, that doesn’t mean we should aim for sharp spikes either. The pronounced spikes and dips in blood sugar levels that some individuals experience throughout the day have been popularly referred to online as a "blood sugar rollercoaster." These can impact mood, and may result in poor health and chronic disease risk, especially when these fluctuations are extreme and ineffectively managed (source, source).

Some studies suggest that sharp spikes especially from high glycemic load (HGL) foods can increase oxidative stress and inflammation, which are risk factors for chronic disease (source). One study even found that high-GI diets were linked with greater fatigue and mood disturbances, while lower-GI diets were associated with improved energy and mood.

Glucose responses and their health impacts are complex and influenced by many factors, which is why nuance matters when interpreting nutrition claims. The issue with narratives like Freelee’s is that they often start with a partial truth. For example, the idea that glucose fluctuations are normal is grounded in science, but it then gets overextended, promoting extremes that encourage people to obsess over the glycaemic impact of every single food.

Freelee says that rises in glucose following carbohydrate-rich meals are not just normal, but “necessary and beneficial.” In Freelee’s words, “without this rise, glucose would not be delivered efficiently to our cells, organs, and brain.”

Kate Hilton, dietitian and founder of Diets Debunked, explains why it isn’t always the case that it is necessary and beneficial for glucose to spike significantly to allow glucose to be delivered to our cells efficiently:

Our insulin levels rise in accordance with our blood glucose levels in a tightly controlled manner, meaning that there is a dose-dependent response to the glucose levels in insulin production (in those without insulin resistance). The sharpness of the spike is not correlated with the efficiency of the rate of glucose absorption; in fact, in many cases (such as insulin resistance), a sharper spike means a prolonged elevated blood glucose, and for these individuals, a sharper spike is more difficult to deal with and does not deliver glucose efficiently.

Fruit can be a part of a healthy diet, whether you have diabetes or not.

If you are not diabetic, you do not need to worry about blood glucose spikes to a significant extent. The quality and variety of foods you are eating will matter more to your health than a blood glucose spike. The best thing you can do to prevent insulin resistance and elevated HbA1c is to have a balanced diet with protein, fats, fibre alongside carbohydrate, to exercise regularly and maintain a healthy weight and body fat percentage.

If you have insulin resistance (IR) or diabetes, you do need to be aware of the impact that blood glucose spikes can have. A post-prandial spike can be elevated in people with IR as they aren't producing as much insulin, meaning your blood glucose will spike higher than someone without IR. Equally, your glucose clearance will be much slower, and so it takes longer for your blood glucose to return to baseline as your insulin production cannot cope with the amount of glucose in your bloodstream. This means that your blood glucose can still be elevated 4+ hours after the meal; and if you eat again during this time, you have to contend with the glucose already in your blood and the glucose in the meal, increasing your time with elevated blood glucose. This means your HbA1c overall may end up higher.

To combat this, we recommend pairing carbohydrates with protein, fat and fibre, and having measured, smaller portion sizes of carbs (about fist sized). This allows the carb to trickle into the blood stream, which gives your pancreas a chance to produce enough insulin to keep your blood glucose levels within range, rather than spiking them significantly out of range and fighting to get them back down to normal.

Again, what is missing here is the insulin resistance issue. Freelee is right in the sense that the less time you have with elevated blood glucose, the lower your HbA1c is going to be; however, the people that are the most concerned with HbA1c (people with diabetes, 90% of whom have insulin resistance) cannot effectively deal with these large spikes in blood glucose. So, the way of eating that she is suggesting (large spikes in blood glucose with nothing to slow them down) would be counterintuitive. The rapid elevation occurs as it would do in an insulin sensitive individual, but then cannot come down as the effectiveness or amount of insulin produced is reduced from what is needed. Therefore, these people have sharp spikes, and then their blood glucose remains elevated for a prolonged time, further increasing what she calls the AUC from what it would be if the carbohydrate had entered the bloodstream in a slow trickle, which is easier to deal with. So instead of the ideal sharp spike and drop she uses as her explanation, they have a sharp spike and a delayed drop, meaning a longer time at an elevated blood glucose level, a larger "AUC" and therefore an increased HbA1c.

Be cautious with advice that frames a food or response as always good or always bad. Scientific research typically highlights trends across populations rather than hard rules for individuals, so extreme claims can overlook important context about overall eating patterns and health.

Tracking blood sugar to avoid "spikes" has become a popular social media trend. In contrast, influencer Leanne Ratcliffe aka ‘Freelee the Banana Girl’ challenges that narrative, arguing that glucose spikes aren't inherently bad and may even be beneficial.

In June 2025, she shared a post on Instagram, in which she argues that flattening blood sugar spikes with high-fat, high-protein meals keeps blood sugar levels high for longer. She says this “long exposure” causes more harm, such as aging faster, storing more fat, and needing more insulin. By contrast, she claims that eating fruit causes a quick spike and drop in blood sugar, which she calls “metabolically clean.”

This fact-check breaks down the science behind blood sugar, explains how fluctuations work, and adds clarity to the ongoing debate.

Note: Before publishing this article, we reached out to Freelee for clarification on her views. Her comments are included throughout this fact-check, alongside professional insights from Registered Dietitians and evidence-based analysis from our research team.

While sharp spikes (even from fruit) can increase oxidative stress and glycation, which are linked to aging and metabolic disease, occasional peaks in otherwise healthy individuals are a normal part of metabolism and not inherently harmful. On the other hand, pairing carbohydrates with fibre, protein, or healthy fats helps moderate blood sugar responses and supports better metabolic outcomes. Claims suggesting fat and protein are harmful for this reason oversimplify how digestion and glucose regulation work.

Blood sugar responses are linked to health outcomes like diabetes, heart disease, and weight gain, so claims about the “best” curve can influence how people choose what to eat. If the idea that sharp sugar spikes are healthier were true, it would challenge much of today’s dietary advice. But if it’s misleading, it could encourage eating habits that raise health risks. That’s why it’s important to check whether the science really supports these claims.

Do very hot tea or coffee raise the risk of esophageal cancer?

Claim 1: Your risk of developing oesophageal cancer is increased if you drink tea, coffee or other drinks at hot temperatures.

Fact-check: The claim that oesophageal cancer risk increases if you drink hot tea, coffee or other drinks lacks context. Let’s take a closer look at the study on which the Express’ article is based to get a better understanding of the links between coffee or tea consumption and cancer.

What the new UK study actually found

According to a large UK Biobank analysis, 454,796 adults were followed for about 12 years and reported both how many cups of tea/coffee they drank and whether they preferred them warm, hot or very hot. The researchers in this study observed that, compared with people who drank warm drinks, choosing hot beverages was linked to a higher risk of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) as daily cups increased. The association was stronger for very hot drinks: for example, ≤4 cups/day was linked to roughly 2.5×higher ESCC risk, and >8 cups/day to around 5.6× higher risk.

Importantly, the same study found no clear association between drink temperature and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), which is a different type of oesophageal cancer.

Absolute numbers of cancer cases remained small (242 ESCC cases and 710 EAC cases), so the individual risk is low in the UK setting according to the analysis. The results were adjusted for factors such as age, sex, smoking and alcohol, but as an observational study they cannot prove that hot drinks cause cancer. This is mainly because the data gathered in this study was self-reported data, such as the temperature of the drinks when consumed, although follow-up checks suggested the results were fairly reliable.

Overall, the pattern suggests a dose–temperature relationship for ESCC that fits with prior evidence from high-risk settings where measured very-hot tea has been linked to higher ESCC risk.

Is it the drink or the temperature?

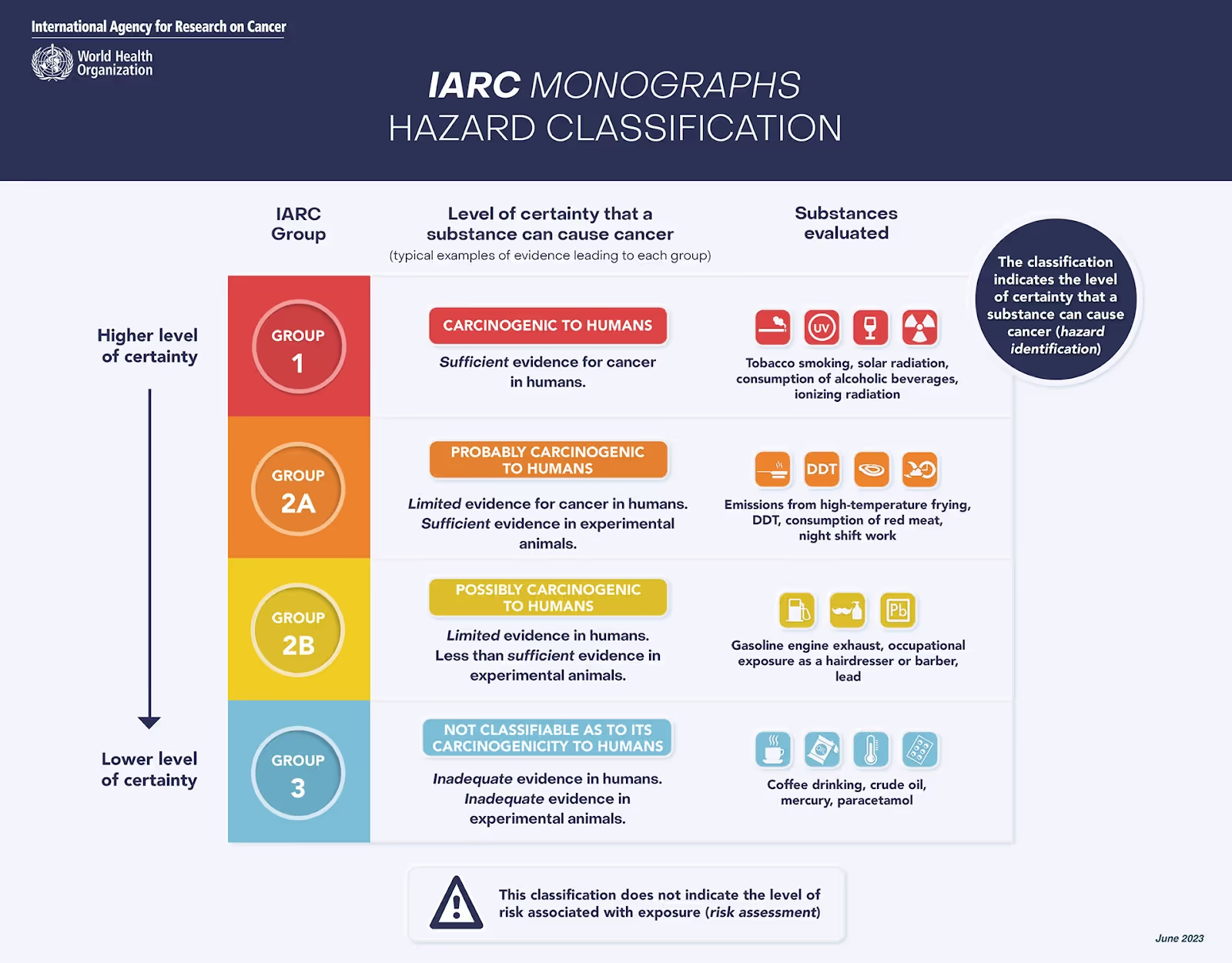

Evidence points to temperature, not the drink itself, as the main concern: the WHO’s cancer agency (IARC) classifies very hot beverages (typically >65 °C) as “probably carcinogenic to humans” based on studies of thermal injury and ESCC.

In the Golestan study in Iran, investigators measured tea temperature and found higher future ESCC risk among people who drank very hot tea compared with cooler tea, reinforcing that heat, not tea, drives risk.

The new UK Biobank results fit this picture, showing higher ESCC risk with increasing temperature preference and number of daily cups, while finding no clear link with EAC.

Animal experiments add biological plausibility: repeated exposure to 70 °C water promoted esophageal cancer risk in mice compared with a chemical carcinogen alone (a substance known to cause cancer in laboratory settings), according to this study.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) also notes that coffee itself is not classified as carcinogenic at usual drinking temperatures, which aligns with the wider literature on coffee’s health profile (The Lancet, BMJ).

Practically, simple changes (letting drinks cool, adding a splash of milk or water, and avoiding gulping many scalding cups) are sensible ways to reduce any thermal-injury risk while keeping the everyday benefits of tea and coffee.

Coffee and tea and overall health

It’s vital that research findings are shared with the public, but without the right context they can easily create a distorted sense of risk, especially for people without a science background. In the case of coffee and tea, the story is not only about possible risks from very hot drinks, but also about the well-documented health benefits these beverages can offer when enjoyed in moderation.

Coffee and tea can both sit comfortably in a healthy, everyday diet. According to a large umbrella review in the BMJ, people who drink about three to four cups of coffee a day tend to have lower risks of early death and cardiovascular disease compared with non-drinkers. A separate meta-analysis (a meta-analysis is when scientists combine the results of many separate studies on the same topic to get a clearer overall picture of what the evidence shows) suggests both caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee are linked with a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, pointing to components beyond caffeine that may be helpful. For tea, scientists analysing the UK Biobank reported that those drinking two or more cups of black tea daily had a modestly lower risk of death from any cause.

How you brew coffee also matters for cholesterol. Randomised controlled trials (source 1, source 2) show that unfiltered coffee (such as boiled coffee or cafetière/French press) contains natural oils (cafestol and kahweol) that can raise LDL (“bad”) cholesterol. Using a paper filter largely removes these oils, so if your LDL is high, scientists recommend opting for paper-filtered coffee as a simple, evidence-based tweak.

On caffeine, European safety assessors conclude that up to 400 mg per day is a safe level for most healthy, non-pregnant adults (roughly four to five small coffees, or six to eight teas, depending on strength), while around 200 mg per day is the advised upper limit during pregnancy. Sensitivity varies: if caffeine makes you jittery or affects your sleep, cutting back or choosing decaf is sensible.

What about hydration? Despite the old myth, research does not support the idea that tea and coffee “dehydrate” you at typical intakes. In the randomised cross-over study, habitual coffee drinkers who consumed several cups of coffee per day showed no differences from water in total body water, urine volume or blood markers of hydration. Reflecting this evidence, European guidance counts all beverages, including caffeinated ones, towards your daily fluid intake targets. In practice, that means your cups of tea or coffee can help meet your fluid needs.

Final take-away

Two practical tips tie this together. First, the temperature matters for oesophageal comfort and safety: let hot drinks cool a little or add a splash of milk or water before sipping. Second, enjoy coffee and tea mostly unsweetened; keeping added sugars low supports cardiometabolic health. With these simple steps, coffee and tea can be enjoyable, hydrating parts of a balanced diet.

We have contacted Express and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Avoid Clickbait Traps: Headlines can be misleading. Read beyond the headline to understand the real story.

A UK newspaper reported that drinking very hot tea or coffee could raise your risk of cancers of the oesophagus (food pipe), citing a large UK Biobank study. Here’s what the science actually says, in plain language, and how this fits alongside what we know about coffee, tea and health more broadly.

Drinking lots of tea or coffee when it’s very hot may raise the risk of cancer of the oesophagus because of the heat, not the drink itself. Letting it cool a little is sufficient to reduce the risk. Moderate, not-too-hot tea and coffee are part of a healthy, hydrating routine.

The findings from the latest UK Biobank analysis relate to temperature (thermal injury) rather than coffee or tea as ingredients.

Hot drinks are part of daily life; many people worldwide rely on hot coffee or tea to kickstart and fuel their workdays. Most people don’t read beyond the headline, which is why framing matters. When headlines oversimplify or misrepresent the science, they can fuel unnecessary worry about everyday habits like drinking tea or coffee. This not only risks making people anxious for no good reason, but also chips away at scientific literacy. For instance, when animal studies are quoted without proper context, readers may be left unable to judge what the findings really mean for humans, or how big the actual risk might be. Clear communication helps people understand the evidence, weigh risks sensibly, and make informed choices about their health.

Does unprocessed red meat cause cancer?

Claim 1: “There is no good evidence that red meat causes cancer.”

Fact-check: This claim overlooks a substantial body of research associating unprocessed red meat with increased risk of several cancers. While processed meats carry a higher risk, unprocessed red meat is not off the hook. A systematic review that included 37 prospective cohort studies and a nested case-control study found a weak but statistically significant association between unprocessed red meat and both colorectal and breast cancers.

Another large meta-analysis of 148 publications on red and processed meat consumption and cancer incidence found that unprocessed red meat was associated with increased risk for breast, endometrial, colorectal, lung, and liver cancers. In dose–response analysis, each 100-gram daily increase in red meat consumption (roughly a 3.5 oz steak) was linked to an 11% higher risk of breast cancer, a 14% higher risk of colorectal cancer, a 17% increase in colon cancer, a 26% increase in rectal cancer, and a 29% increase in lung cancer.

These findings are supported by the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), which evaluated more than 800 epidemiological studies. The IARC classified unprocessed red meat as a Group 2A carcinogen, meaning it is “probably carcinogenic to humans,” based on evidence linking it primarily to colorectal cancer, as well as pancreatic and prostate cancers. This classification puts red meat just one tier below processed meat, which is in Group 1 (“carcinogenic to humans”). While red meat alone is not considered a strong carcinogen, dismissing the risks entirely is inconsistent with the available evidence.

Claim 2: “And in fact, it [red meat] may protect you against it [cancer].”

Fact-check: The suggestion that red meat protects against cancer is speculative and not supported by human data. Saladino references a list of compounds found in animal foods—such as trans-vaccenic acid (TVA), taurine, creatine, carnitine, anserine, and 4-hydroxyproline—as having anticancer properties. While preclinical research has studied the potential roles of these compounds in immune modulation or tumor biology, the evidence remains preliminary.

Biological mechanisms vs. real-world health outcomes

For example, taurine, TVA, and creatine have been shown in animal and cell studies to enhance CD8+ T cell activity, which plays a role in cancer immunosurveillance. Carnitine is involved in fatty acid metabolism, a process that some cancer cells may exploit to support their growth and survival. Anserine may enhance the effectiveness of doxorubicin, a chemotherapy drug, in preclinical models, but it has not been shown to have anticancer effects on its own. And 4-hydroxyproline, found in collagen, is being explored for its potential role in reshaping the environment around tumors, which plays a role in how cancers grow, spread, and respond to treatment.

These findings are interesting, but the majority of them come from in vitro or animal studies and are not backed by clinical research in humans. Translating biological effects seen in rodents or isolated cells into real-world human health outcomes is fraught with challenges. Without rigorous human trials, there is no credible basis to claim that red meat consumption provides a protective effect against cancer. The presence of potentially beneficial compounds in a food does not cancel out the overall epidemiological signal suggesting harm.

Claim 3: “…there are simply zero randomized controlled trials in humans showing that more red meat is either inflammatory or increases your risk of cancer.”

Fact-check: While it is true that there are no long-term randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showing a causal relationship between red meat intake and cancer, this is not unusual in nutrition science and does not undermine the broader evidence base. Long-term RCTs examining diet and chronic disease are extremely difficult to conduct due to logistical, financial, and ethical constraints. It is not feasible or ethical to assign participants to consume high quantities of a suspected carcinogen for decades.

As a result, nutrition science often relies on large-scale, prospective cohort studies. When designed well and replicated across multiple populations, epidemiological studies can provide strong evidence of risk. These types of studies have been critical in establishing now-undisputed links between smoking and lung cancer, trans fats and heart disease, and sugar-sweetened beverages and type 2 diabetes—all in the absence of long-term RCTs.

Some short-term RCTs have looked at red meat and intermediate markers of disease risk, such as inflammation or cholesterol levels. For example, a meta-analysis of 36 randomized trials with an average study duration of 8.5 weeks evaluated red meat consumption against cardiovascular risk factors. However, short-term trials are limited in their ability to detect long-latency outcomes like cancer, which can take decades to develop. The absence of RCTs should not be interpreted as evidence of no risk, but rather a reflection of the complexity of studying diet and disease in human populations.

Final take-away

Saladino’s claims misrepresent the state of nutritional science by dismissing the well-established links between red meat and cancer, overstating early-stage findings on meat-derived compounds, and minimising the value of decades of epidemiologic research. While red meat can be included in a balanced diet, current evidence consistently shows that regular consumption, particularly in large amounts, is associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer and potentially other cancers.

There is no compelling evidence from human studies that red meat protects against cancer. Selective use of preclinical data to make sweeping health claims, while ignoring the broader body of high-quality human research, does not offer a reliable basis for dietary guidance.

We have contacted Paul Saladino and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Be cautious with claims that reject the scientific consensus and draw mainly from early-stage research that has not been widely explored or replicated.

A common sentiment, especially among proponents of carnivore or animal-based diets, is that unprocessed red meat is not only harmless, but may even be protective against cancer. One vocal advocate of this claim is Paul Saladino, MD, who stated in a viral Instagram post:

“There is no good evidence that red meat causes cancer. And in fact, it may protect you against it. There are multiple nutrients found exclusively or predominantly in red meat that have been found in research studies to be protective against cancers, and there are simply zero randomized controlled trials in humans showing that more red meat is either inflammatory or increases your risk of cancer…”

This fact-check evaluates the accuracy of these claims against current scientific evidence.

While no single food guarantees or prevents cancer, the scientific consensus suggests that regular consumption of red meat, even unprocessed, can modestly increase cancer risk, particularly colorectal cancer. Current evidence does not support the idea that red meat is cancer-protective in humans.

Nutrition misinformation, especially around cancer, spreads rapidly on social media. While it’s true that not all cancer-related food claims are grounded in science, dismissing decades of epidemiological research in favour of anecdotal evidence or preclinical studies is dangerous. Contrary to what some wellness influencers claim, only a few foods are recognised by global health authorities as probable or known carcinogens: alcohol, processed meats, salted/preserved fish, and yes, unprocessed red meat.

Latest fact-checks, guides & opinion pieces

.svg)