The surprising reality about blood sugar spikes (it’s not what you think)

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

Tracking blood sugar to avoid "spikes" has become a popular social media trend. In contrast, influencer Leanne Ratcliffe aka ‘Freelee the Banana Girl’ challenges that narrative, arguing that glucose spikes aren't inherently bad and may even be beneficial.

In June 2025, she shared a post on Instagram, in which she argues that flattening blood sugar spikes with high-fat, high-protein meals keeps blood sugar levels high for longer. She says this “long exposure” causes more harm, such as aging faster, storing more fat, and needing more insulin. By contrast, she claims that eating fruit causes a quick spike and drop in blood sugar, which she calls “metabolically clean.”

This fact-check breaks down the science behind blood sugar, explains how fluctuations work, and adds clarity to the ongoing debate.

Note: Before publishing this article, we reached out to Freelee for clarification on her views. Her comments are included throughout this fact-check, alongside professional insights from Registered Dietitians and evidence-based analysis from our research team.

While sharp spikes (even from fruit) can increase oxidative stress and glycation, which are linked to aging and metabolic disease, occasional peaks in otherwise healthy individuals are a normal part of metabolism and not inherently harmful. On the other hand, pairing carbohydrates with fibre, protein, or healthy fats helps moderate blood sugar responses and supports better metabolic outcomes. Claims suggesting fat and protein are harmful for this reason oversimplify how digestion and glucose regulation work.

Blood sugar responses are linked to health outcomes like diabetes, heart disease, and weight gain, so claims about the “best” curve can influence how people choose what to eat. If the idea that sharp sugar spikes are healthier were true, it would challenge much of today’s dietary advice. But if it’s misleading, it could encourage eating habits that raise health risks. That’s why it’s important to check whether the science really supports these claims.

Be cautious with advice that frames a food or response as always good or always bad. Scientific research typically highlights trends across populations rather than hard rules for individuals, so extreme claims can overlook important context about overall eating patterns and health.

Claim 1: “You want to spike your blood glucose.”

Fact-check: The wording here is what might be problematic: saying that “you want to spike your blood glucose” or “aim for glucose spikes” implies that these spikes are beneficial, and that we should then deliberately try to raise our blood sugar. When we reached out to Freelee for comment, she provided an important clarification, explaining that “when [she speaks] about “aiming for glucose spikes,” [she’s not] suggesting uncontrolled hyperglycemia.” Rather, she is referring to the normal, physiological rise in blood glucose that follows a meal. Freelee describes this rise as “normal, necessary, and beneficial.” Let’s break down what happens to your blood sugar when you eat: what’s normal, and what’s not.

Fluctuations are normal…

Blood sugar levels (also known as glucose levels) indicate the amount of glucose present in the bloodstream, after the body processes carbohydrates from food and beverages daily. It is normal for these levels to rise and fall throughout the day, although individuals with diabetes experience more frequent and heightened fluctuations. It is important not to demonise glucose, a narrative often circulating online, as glucose is a vital energy source for your brain, muscles and tissues (source).

Hypoglycaemia, or low blood sugar, occurs when blood glucose levels fall below 4mmol/litre. This is typically rare in individuals who do not have diabetes (source). Hyperglycaemia, or high blood sugar can also take place when blood glucose levels are higher than 7mmol/litre, usually impacting individuals with diabetes (source).

Some experts have criticised influencers like the Glucose Goddess for pathologising a completely normal phenomenon: glucose fluctuations. For example, Dr Gary McGowan has spoken widely about this topic in several videos, such as this one.

…but that doesn’t mean that glucose spikes are beneficial

For individuals without diabetes, there’s no need to micromanage blood sugar spikes or rely on strict eating rules to maintain blood sugar below a set ‘limit’.

But just because flattening every glucose rise isn’t necessary for most people, that doesn’t mean we should aim for sharp spikes either. The pronounced spikes and dips in blood sugar levels that some individuals experience throughout the day have been popularly referred to online as a "blood sugar rollercoaster." These can impact mood, and may result in poor health and chronic disease risk, especially when these fluctuations are extreme and ineffectively managed (source, source).

Some studies suggest that sharp spikes especially from high glycemic load (HGL) foods can increase oxidative stress and inflammation, which are risk factors for chronic disease (source). One study even found that high-GI diets were linked with greater fatigue and mood disturbances, while lower-GI diets were associated with improved energy and mood.

Glucose responses and their health impacts are complex and influenced by many factors, which is why nuance matters when interpreting nutrition claims. The issue with narratives like Freelee’s is that they often start with a partial truth. For example, the idea that glucose fluctuations are normal is grounded in science, but it then gets overextended, promoting extremes that encourage people to obsess over the glycaemic impact of every single food.

Freelee says that rises in glucose following carbohydrate-rich meals are not just normal, but “necessary and beneficial.” In Freelee’s words, “without this rise, glucose would not be delivered efficiently to our cells, organs, and brain.”

Kate Hilton, dietitian and founder of Diets Debunked, explains why it isn’t always the case that it is necessary and beneficial for glucose to spike significantly to allow glucose to be delivered to our cells efficiently:

Our insulin levels rise in accordance with our blood glucose levels in a tightly controlled manner, meaning that there is a dose-dependent response to the glucose levels in insulin production (in those without insulin resistance). The sharpness of the spike is not correlated with the efficiency of the rate of glucose absorption; in fact, in many cases (such as insulin resistance), a sharper spike means a prolonged elevated blood glucose, and for these individuals, a sharper spike is more difficult to deal with and does not deliver glucose efficiently.

Claim 2: Fat-containing meals “may blunt the early rise [in glucose] but cause a glucose drag (a delayed and prolonged elevation), leading to greater overall exposure” to glucose.

Fact-check: When asked to clarify her position on the benefits of sharper spikes, Freelee further discussed the notion of “glucose drag”. However, the claim that fat and protein cause “glucose drag” overlooks their key role in moderating blood sugar responses. Pairing carbohydrates with fibre, fat, or protein slows digestion and flattens the glycaemic response, something consistently shown to support long-term glucose control.

Freelee supports her argument by making a distinction between glucose spikes and ‘the area under the curve (AUC)’. In Freelee’s words, “AUC represents the total glucose exposure over time, and it is this exposure that correlates most directly with HbA1c, the clinical marker of three-month average glucose. In other words, larger or prolonged AUC translates into higher HbA1c values, whereas brief, contained spikes with rapid clearance do not.” From this, she concludes on the benefits of fruit-based meals, arguing that these produce a sharp but short-lived rise in glucose, which is followed by a rapid return to baseline. These are complex issues, which dietitian Kate Hilton helps us to unpack and contextualise:

Again, what is missing here is the insulin resistance issue. Freelee is right in the sense that the less time you have with elevated blood glucose, the lower your HbA1c is going to be; however, the people that are the most concerned with HbA1c (people with diabetes, 90% of whom have insulin resistance) cannot effectively deal with these large spikes in blood glucose. So, the way of eating that she is suggesting (large spikes in blood glucose with nothing to slow them down) would be counterintuitive. The rapid elevation occurs as it would do in an insulin sensitive individual, but then cannot come down as the effectiveness or amount of insulin produced is reduced from what is needed. Therefore, these people have sharp spikes, and then their blood glucose remains elevated for a prolonged time, further increasing what she calls the AUC from what it would be if the carbohydrate had entered the bloodstream in a slow trickle, which is easier to deal with. So instead of the ideal sharp spike and drop she uses as her explanation, they have a sharp spike and a delayed drop, meaning a longer time at an elevated blood glucose level, a larger "AUC" and therefore an increased HbA1c.

A key issue with health advice on social media is that we don’t always know who the audience is. As Kate also points out,

“People who don't have glycaemic control issues don't necessarily have to be worrying about blood glucose spikes as their pancreas can manage it effectively, and perhaps this is the audience Freelee is trying to target with this advice. However if this is the case, these individuals aren't worrying about their HbA1c anyway. The people who do have to worry might be the people who would be listening to this messaging, aka people with type 2 diabetes or insulin resistance, and thus this messaging is harmful for their glycaemic control.”

This highlights the potential danger of extreme-sounding claims: the people most likely to take them seriously might be the ones for whom the advice may be most harmful.

Rather than hyperfixating on individual glucose readings, the evidence supports a more balanced approach: eating a variety of whole, minimally processed foods, including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, protein sources, and healthy fats. This supports stable energy, reduces risk of disease, and avoids the pitfalls of extreme or overly simplistic dietary advice.

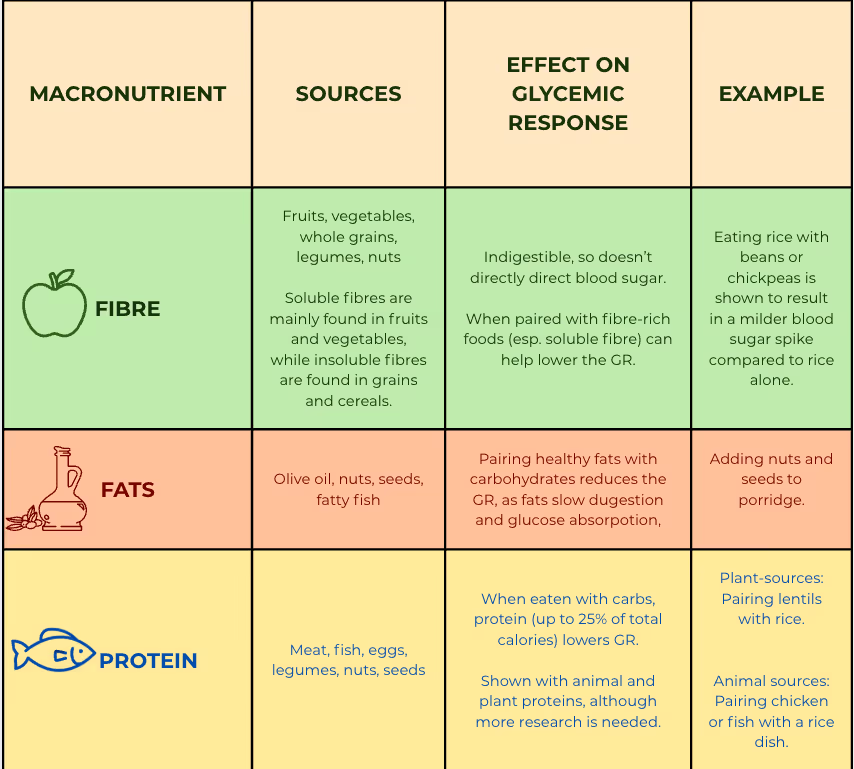

Combining foods to modulate glycemic response (GR)

The glycemic impact of a food can change when eaten alongside other nutrients. For example, pairing carbohydrate-rich foods with those high in fibre, fat, or protein slows gastric emptying, delaying carbohydrate absorption and reducing the GR (source, source). Carbohydrates are the body’s main source of glucose, typically digesting within 1–2 hours. Those high in fibre, like whole grains, beans, and lentils, digest more slowly and help moderate glucose absorption. Protein, on the other hand, has little effect on blood sugar, as it doesn’t convert directly to glucose. It digests more slowly than carbs, usually over 3–4 hours. Fat slows digestion overall, delaying the rise in glucose after a meal. While moderate fat intake has minimal impact, excessive amounts may contribute to insulin resistance and prolonged elevated blood sugar.

Eating balanced meals and snacks throughout the day, while combining high-fibre carbs, lean protein, and healthy fats, can help maintain steady glucose levels, supporting energy and satiety (source).

Claim 3: Fruit sugar is metabolically “clean”

Fact-check: The claim that fruit sugar is uniquely “clean” oversimplifies how the body processes sugars, especially when it comes to glycation and metabolic health.

Glycation happens when certain sugars stick to proteins, fats, or DNA in the body, forming harmful compounds called Advanced Glycation Endproducts (AGEs). These AGEs can damage how proteins work (source). Eating too much sugar, and especially fructose from sources like fruit, may speed this process up, since fructose is more reactive than glucose (source). Studies show that fructose causes glycation much faster than glucose in lab tests (source, source). Over time, high levels of AGEs can disrupt fat metabolism, trigger inflammation, and damage the body’s energy systems, all of which raise the risk of metabolic diseases (source).

It is worth noting that FreeLee’s focus on raw, unprocessed fruit has some benefits for glucose control.

Food processing breaks down natural structures, making nutrients more accessible for digestion and increasing blood sugar responses. Therefore, choosing whole, unprocessed foods over refined alternatives is recommended to help stabilise glucose levels (source). While eating unprocessed foods and ensuring you are eating enough plants is important, the NHS recommendations currently suggest that at least 5 portions of fruit and vegetables a day is optimal.

Final take away

In her response to us, Freelee supported her arguments with numerous scientific sources. However, several of these are drawn from clinical contexts that don’t necessarily apply to the general population, such as studies on type 1 diabetes or complications like gastroparesis. Registered Dietitian Leah McGrath notes that others are outdated, with some more than a decade old despite frequent updates in diabetes research and guidelines. In some cases, the sources are overgeneralised or taken out of context. For example, a study on kiwi fruit (a low-glycaemic fruit) is used to support claims about all fruit, and a paper on fructose metabolism is cited without acknowledging that it also describes adverse effects such as insulin resistance. This pattern of selecting sources that appear supportive while overlooking limitations is common in nutrition messaging on social media and can end up undermining nutrition literacy.

Nutrition and metabolism are (sometimes frustratingly) complex and nuanced, and when those nuances are lost, it can leave us more confused. This is how we end up with some influencers urging us to do everything possible to “flatten glucose spikes” (often while promoting supplements), while others swing the other way, encouraging diets made up largely of fruit and glucose.

It’s understandable that this mix of advice can feel overwhelming. Ultimately, the overemphasis on glucose itself is not helpful. Hyper-focusing on it can demonise certain foods, lead to unnecessary restriction, and create a stressful relationship with eating, when food should be both nourishing and enjoyable.

The encouraging part is that the reality is less extreme than the narratives that are found circulating online, and there are simple, evidence-based habits that support overall health, and which dietitian Kate Hilton summarises below, in the final Expert Weigh-In.

Disclaimer

This fact check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

We also recognise that there are many other aspects of glucose metabolism, diet, and health that could continue and deepen this conversation. The purpose here is to clarify the main points of the claim and to contextualise the way in which social media conversations sometimes use scientific concepts in ways that can oversimplify or mislead.

For readers interested in learning more, we recommend following accounts by specialists who cover these topics in greater depth, such as Dr Nicola Guess or Kate Hilton at Diets Debunked.

We would also like to thank Freelee for taking the time to share her clarifications with us.

Fruit can be a part of a healthy diet, whether you have diabetes or not.

If you are not diabetic, you do not need to worry about blood glucose spikes to a significant extent. The quality and variety of foods you are eating will matter more to your health than a blood glucose spike. The best thing you can do to prevent insulin resistance and elevated HbA1c is to have a balanced diet with protein, fats, fibre alongside carbohydrate, to exercise regularly and maintain a healthy weight and body fat percentage.

If you have insulin resistance (IR) or diabetes, you do need to be aware of the impact that blood glucose spikes can have. A post-prandial spike can be elevated in people with IR as they aren't producing as much insulin, meaning your blood glucose will spike higher than someone without IR. Equally, your glucose clearance will be much slower, and so it takes longer for your blood glucose to return to baseline as your insulin production cannot cope with the amount of glucose in your bloodstream. This means that your blood glucose can still be elevated 4+ hours after the meal; and if you eat again during this time, you have to contend with the glucose already in your blood and the glucose in the meal, increasing your time with elevated blood glucose. This means your HbA1c overall may end up higher.

To combat this, we recommend pairing carbohydrates with protein, fat and fibre, and having measured, smaller portion sizes of carbs (about fist sized). This allows the carb to trickle into the blood stream, which gives your pancreas a chance to produce enough insulin to keep your blood glucose levels within range, rather than spiking them significantly out of range and fighting to get them back down to normal.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources

World Health Organization (2024). Diabetes.

Diabetes UK. Checking Your Blood Sugar Levels.

EUFIC (2013). Glucose and The Brain: Improving Mental Performance.

NHS UK. Low Blood Sugar (hypoglycaemia).

NHS UK. High Blood Sugar (hyperglycaemia).

Breymeyer, K.L. et al. (2016). Subjective mood and energy levels of healthy weight and overweight/obese healthy adults on high- and low-glycemic load experimental diets.

Blaak, E.E. et al. (2012). “Impact of postprandial glycaemia on health and prevention of disease.”

Henry, C.J.K. et al. (2006). The impact of the addition of toppings/fillings on the glycaemic response to commonly consumed carbohydrate foods.

Chiavaroli, L. et al. (2021). The importance of glycemic index on post-prandial glycaemia in the context of mixed meals: a randomized controlled trial on pasta and rice.

Åberg, S. et al. (2020). Whole-grain processing and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a randomized crossover trial.

Bunn & Higgins (1981). Reaction of monosaccharides with proteins: Possible evolutionary significance.

Tagaki, Yl. et al. (1995). Significance of fructose-induced protein oxidation and formation of advanced glycation end product.

Aragno, M. & Mastrocola, R. (2017). Dietary Sugars and Endogenous Formation of Advanced Glycation Endproducts: Emerging Mechanisms of Disease.

Uribarri, J. et al. (2010). Advanced Glycation End Products in Foods and a Practical Guide to Their Reduction in the Diet

Joslin Diabetes Center (2021). Understanding Food’s Impact on Glucose Levels

Loader, J. et al. (2015). Acute Hyperglycemia Impairs Vascular Function in Healthy and Cardiometabolic Diseased Subjects: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

NHS. The Eatwell Guide.

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)