Garlic and blood pressure: what the evidence shows and what it doesn’t

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

Eric Berg, D.C. recently remarked that pharmaceutical companies were “heavily researching garlic for its blood thinning properties,” asking his audience: “Instead of waiting for them to produce a drug that mimics its effects, why not just eat garlic?”

This fact-check digs deeper into the science behind garlic and hypertension, and looks closer at the logic behind this post: what are its implications, and are they backed by scientific evidence?

The facts: garlic can play a helpful role in supporting heart health, and a balanced diet is key to long-term prevention.

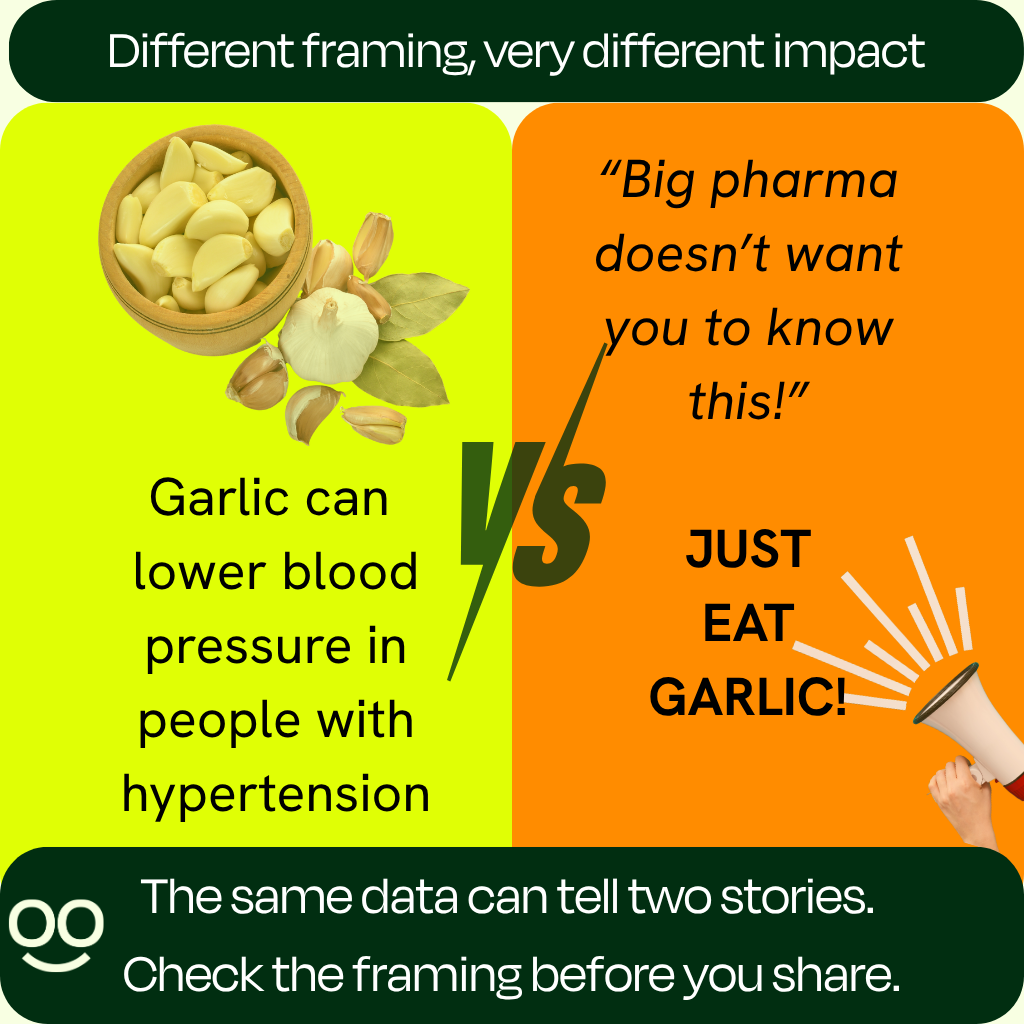

The framing: posts like this often present those findings to imply that drugs merely mimic food effects, suggesting a false choice between natural and medical care. In reality, evidence-based care can combine both: using diet to lower baseline risk and medication when needed to keep it under control.

When posts on social media suggest that eating certain foods like garlic makes drugs unnecessary, the problem lies not only in the facts themselves but in how those facts are presented, in a way that undermines evidence-based care. Communication matters. Language does more than transfer information; it shapes how people reason about food, health, and risk. This is why fact-checks must pay attention to tone and framing, as well as factual accuracy. Ultimately, distrust in medical interventions could lead some people to turn away from evidence-based treatments and have negative consequences for their health.

Be skeptical of one-sided arguments: Valid information considers multiple perspectives.

Let’s start with a bit of context: what is hypertension? And how can eating garlic affect blood pressure?

What is hypertension?

Hypertension means blood pressure that stays too high over time (typically confirmed in UK practice at ≥140/90 mmHg in clinic or ≥135/85 mmHg at home). It is a leading modifiable risk factor for heart disease and stroke (source, source).

Hypertension usually causes no symptoms, which is why it often goes undetected, but the good news is that it can be effectively controlled with lifestyle changes (including dietary changes) and medication when needed (source).

A recent study dispelled the commonly shared idea that cardiovascular events strike without warning. The researchers analysed health records from two large cohorts (over 9 million individuals in South Korea and nearly 7,000 in the U.S.). They found that 99% of those who experienced a stroke, heart failure, or coronary heart disease had at least one major risk factor (such as blood pressure, cholesterol, or glucose) at non-optimal levels. Notably, they found that high blood pressure was the most commonly present risk factor, found in more than 95% of South Korean patients and over 93% of U.S. patients.

This highlights the importance of prevention. In that sense, emphasising the benefits of garlic consumption to support healthy blood pressure can indeed be beneficial to the general public. However, this should not come at the expense of guidance from health professionals, or dismissal of effective medical treatments. Dietary and medical interventions should be seen as complementary tools rather than in competition when addressing such a prevalent global health issue.

What Eric Berg’s post gets right

To start with the good news: there are plenty of reasons to eat garlic. It provides vitamin C, vitamin B6, selenium, and fibre, alongside sulphur-containing compounds that play active roles in the body.

Garlic has long been studied for cardiovascular benefits. It is thought to help lower high blood pressure mainly because it contains natural sulfur compounds (especially allicin and S-allylcysteine) that help blood vessels relax, improve how they widen, and reduce inflammation and oxidative stress. These effects make it easier for blood to flow and can modestly lower blood pressure over time.

Clinical studies, particularly those using aged garlic extract or standardised garlic powders, show that garlic supplementation can reduce high blood pressure in people with hypertension and has potential for cardiovascular protection (source, source). In one randomised controlled trial, participants who took two capsules of aged garlic extract daily saw an average reduction in systolic blood pressure of 11.8±5.4 mm Hg compared with those taking a placebo (P=0.006). The “± 5.4 mmHg” shows how much this effect varied among participants, and the reported P = 0.006 indicates that this difference was statistically significant, meaning it was unlikely to have occurred by chance.

In practical terms, this means that taking aged garlic extract in this study led to a measurable and statistically reliable drop in systolic blood pressure. That change is large enough to be clinically meaningful: large-scale analyses show that lowering systolic blood pressure by 10 mmHg reduces the risk of coronary heart disease by about a quarter, and the risk of stroke by about one-third, with similar benefits across different patient groups (source).

However, the presence of beneficial compounds in a food doesn’t automatically mean that eating it will reproduce the same effects seen in controlled supplement trials. This distinction, between a nutrient’s potential in theory and its measurable impact in everyday diets, is an important component of nutrition science. Before drawing conclusions, researchers must ask key questions: how much of the active compound is absorbed from food? Is this an achievable amount for people to consume daily? How stable is it after cooking or digestion? How does it interact with other nutrients, and how consistent are its effects between individuals? The same reasoning applies to other foods rich in promising compounds, such as flavonoids in dark chocolate or resveratrol in red wine: both show cardiovascular benefits in studies, but that doesn’t mean eating chocolate or drinking wine daily will yield the same outcomes. These are the caveats scientists must address before moving from lab findings to everyday health guidance.

It is in this context that the above results from trials on garlic supplementation and hypertension should be interpreted. Firstly, studies consistently emphasise that garlic shows promise as a “complementary treatment option” for hypertension (source, source), rather than as a replacement. Secondly, the effects are most consistent in people who already have high blood pressure (source). Finally, the form of garlic (fresh cloves, powders, oils, aged extracts) matters, as does the dose. Many trials used capsules delivering controlled amounts of allicin or S-allylcysteine, which raw garlic cannot reliably provide. And results across studies vary, leading review authors to stress that more large, long-term research is needed before confident guidance can be offered.

Can we “just eat garlic” in the meantime? Absolutely, but leaving out the above information about how scientists move from observed properties to effective medical treatments can leave readers with a distorted understanding of the purpose, use, and context of such medications.

Why the message misleads

Logic leap: can food replace drugs?

Issues arise from the suggestion that garlic can replace drugs altogether. Indeed the post does not just boast the benefits of garlic. It suggests that pharmaceutical drugs merely mimic the effects of food, appealing to the message that ‘you don’t need medication if you eat the right foods’, which is prevalent on social media. This idea sounds empowering, but it also oversimplifies a complex reality. High blood pressure often involves multiple underlying processes, and while garlic may support its management, other interventions and treatments should be acknowledged too. Check out our guide for spotting misused research on social media.

A recent review on garlic and hypertension puts it clearly: “while garlic may offer benefits, it should not be considered a substitute for conventional medications.” The same review notes that many patients with hypertension already distrust drugs, turning instead to herbal remedies. In this context, posts like this risk deepening that distrust, possibly nudging people away from treatments whose efficacy has been proven to significantly reduce the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

Garlic does influence nitric oxide and hydrogen sulphide pathways, relaxing blood vessels and reducing platelet stickiness (source). But its effects depend on how the garlic is grown, stored, prepared, and digested: variables that make allicin content unpredictable. Genetics and nutrient status can also influence how effectively the body converts garlic’s compounds into the molecules that help regulate blood pressure, so individual responses may vary. This is important, because it means that for some people, supportive nutrition and lifestyle habits might not be enough to effectively manage blood pressure. As British Heart Foundation dietitian Victoria Taylor notes, while garlic is associated with cardiovascular effects, there is “not much hard evidence” that eating cloves alone can deliver consistent therapeutic outcomes (source).

Medications are developed to isolate a mechanism, deliver controlled doses, and produce reproducible results across patients, essential qualities for managing high-risk conditions like hypertension.

Packaging that fuels distrust

The framing of posts like Eric Berg’s feeds a familiar narrative: that “Big Pharma” hides nature’s cures to sell synthetic alternatives. This framing resonates emotionally because it offers both control and simplicity: food feels familiar, while pharmaceuticals aren’t, and they generate profit. But this creates a false dichotomy.

Take the World Health Organisation’s HEARTS Technical Package as an example. Its aim is to provide a public health approach to hypertension and cardiovascular disease (CVD) management in primary care. And it begins with lifestyle: diet, exercise, salt reduction, weight control, and quitting smoking. Those are foundations that can then be layered with standardised treatment protocols and medications where deemed necessary.

This structure is significant. Far from the image of doctors just wanting to prescribe pills, the most respected global protocols start with lifestyle and build up to medication when risk warrants it.

Bottom line: what’s the difference between eating garlic, taking garlic supplements, or taking medication?

While fresh, raw, or cooked garlic can be a healthy addition to a balanced diet, its active compounds, such as allicin, are unstable and vary widely depending on how the garlic is prepared, stored, or even chopped. That means it’s very difficult to know how much of the beneficial compounds you’re actually getting from food alone.

Garlic supplements are therefore designed to concentrate those compounds, but not all are created equal. Research shows that aged garlic extract currently appears to be a more reliable form for blood pressure support because it contains S-allylcysteine, a stable compound that allows for consistent dosing. Aged garlic extract has also been found to not increase bleeding risk when taken with blood-thinning medications (source).

Medications are standardised, tightly regulated, and backed by extensive clinical data showing they lower blood pressure predictably and reduce the risk of heart attack, stroke, and death. Garlic, especially in its aged extract form, can complement this approach. Which option is most appropriate will depend on individual risk and medical history, so decisions about supplements or medication should always be made in consultation with a doctor.

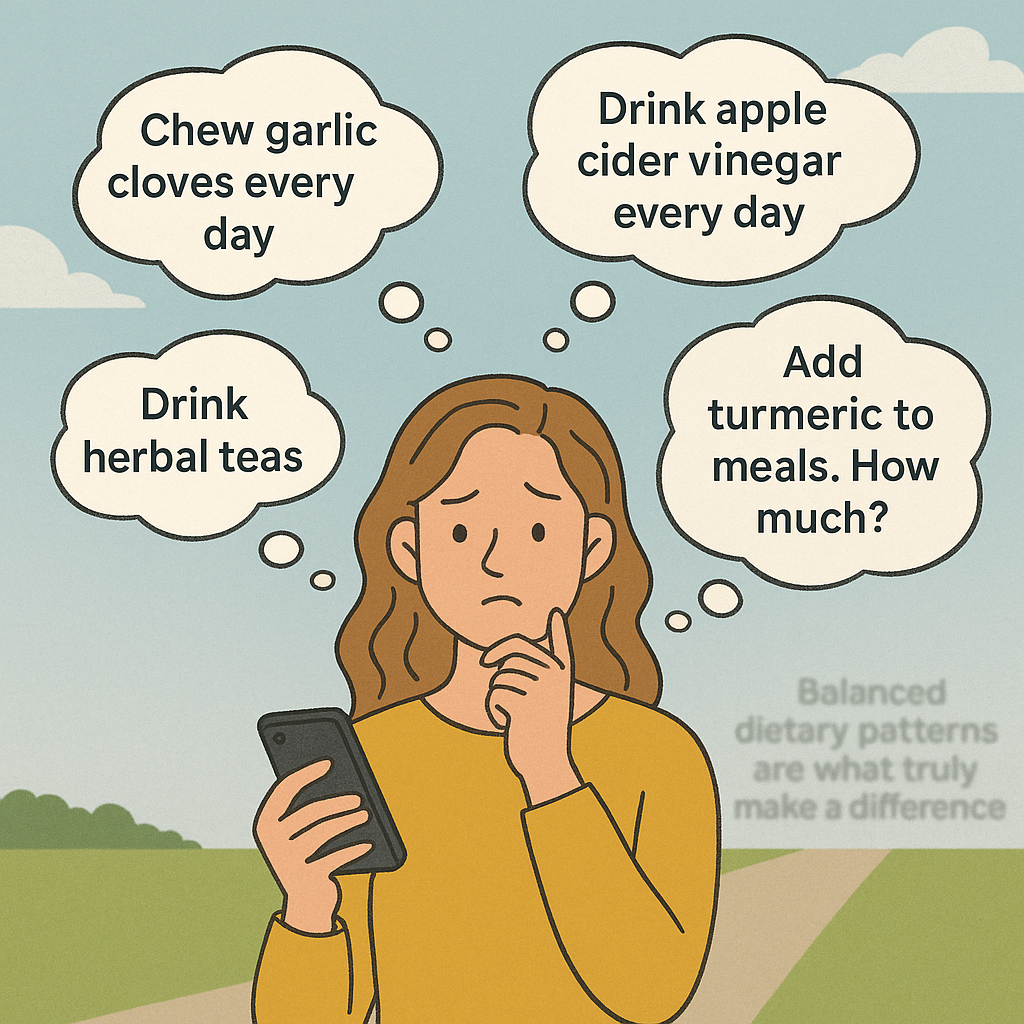

The problem with single-food narratives

It is absolutely true that lifestyle changes can meaningfully reduce blood pressure. But regularly focusing on single ingredients distorts the picture of how nutrition works. Social media thrives on spotlighting one miracle food at a time: garlic today, turmeric tomorrow, lemon water the next day. This can turn nutrition into a never-ending checklist of daily ‘rituals’. Should you eat two raw garlic cloves every morning? Add turmeric to every meal? Brew endless herbal teas? For a lot of people this becomes overwhelming, distracting from what actually works. This is generally evident in the comments section of such posts, where people are often seeking clarification as to how to incorporate these foods into their diet to make a practical difference.

What research consistently shows is that long-term health depends on overall patterns: diets rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains and fibre, while limiting saturated fats, processed foods, and excess sugar.

The supplement contradiction

There is also a contradiction worth noting. Many influencers who warn against “Big Pharma” promote supplements as a solution to many health-related problems. Yet it is important to remind the public that supplements are less regulated than medicines. Their purity, dosage, and claims are not always tested to the same standard.

In the U.S., supplements fall under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA), which allows products to be sold without FDA pre-approval as long as they don’t claim to treat disease. In Europe, garlic supplements are classified as food supplements under the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), which authorises only generic claims like “maintenance of heart health.”

Clinically studied products such as Kyolic Aged Garlic Extract stand out because they use standardised preparations containing S-allylcysteine, the same compound linked to garlic’s cardiovascular benefits (source). But many retail supplements vary widely in potency, making consistency, effectiveness and safety uncertain.

Beyond this fact-check: the big picture

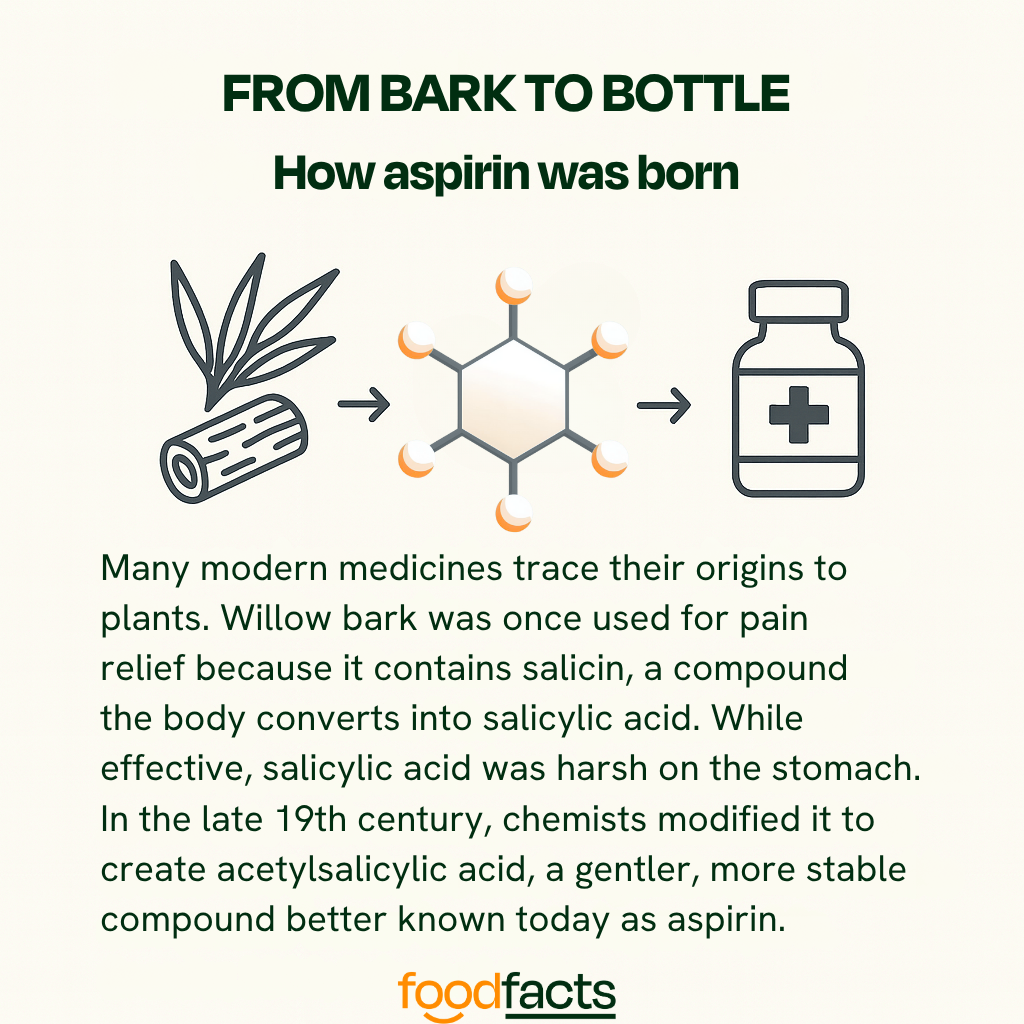

As with all nutrition questions, balance matters. Without it, nutrition advice can slip into rigid rules that overpraise or demonise foods, missing the broader dietary patterns that truly support long-term health. Understanding how these processes work, how foods interact with biological systems, and how natural compounds can inspire medical treatments, is essential for making informed, evidence-based decisions.

Promoting healthy foods is important, because diet plays a central role in preventing disease and supporting overall well-being. But it’s equally important to recognise that food alone cannot always correct complex conditions once they develop. Medical treatments often build on nature’s chemistry, refining it to create safe, consistent, and targeted therapies. This is a principle that extends far beyond garlic, and far beyond this fact-check, as this final example illustrates:

Final take away

Enjoy garlic as part of your diet, but don’t rely on it to replace prescribed blood-thinning medication. Instead of seeing it as food versus medicine, it’s more accurate, and empowering, to see them working together.

We have contacted Eric Berg, D.C. and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources

Ried, K. (2019). “Garlic lowers blood pressure in hypertensive subjects, improves arterial stiffness and gut microbiota: A review and meta-analysis.”

U.S.F.D.A. “Dietary supplements”

Ried, K. et al. (2013). “Aged garlic extract reduces blood pressure in hypertensives: a dose–response trial.”

WHO (2018). “HEARTS: Technical package for cardiovascular disease management in primary health care: Healthy-lifestyle counselling.”

British Heart Foundation (2018). “Is garlic good for your heart?.”

Rahman, K. & Billington, D. (2000). “Dietary Supplementation with Aged Garlic Extract Inhibits ADP-Induced Platelet Aggregation in Humans.”

Sleiman, C. et al. (2024). “Garlic and Hypertension: Efficacy, Mechanism of Action, and Clinical Implications.”

Ried, K. & Fakler, P. (2014). “Potential of garlic (Allium sativum) in lowering high blood pressure: mechanisms of action and clinical relevance.”

Ried, K. (2016). “Garlic Lowers Blood Pressure in Hypertensive Individuals, Regulates Serum Cholesterol, and Stimulates Immunity: An Updated Meta-analysis and Review.”

Weiskirchen , S. & Weiskirchen, R. (2016). “Resveratrol: How Much Wine Do You Have to Drink to Stay Healthy?”

BMJ (2009). “Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies.”

Varshney, R. & Budoff, M.J. (2016). “Garlic and Heart Disease.”

Lee, H. et al. (2025). “Very High Prevalence of Nonoptimally Controlled Traditional Risk Factors at the Onset of Cardiovascular Disease.”

WHO (2025). “Global report on hypertension 2025.”

British Journal of General Practice (2020). “Diagnosis and management of hypertension in adults: NICE guideline update 2019.”

Rainsford, K.D. (2004). “History and Development of the Salicylates.”

BMJ (2000). “The discovery of aspirin: a reappraisal.”

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)