How analogies shape nutrition debates: power and limitations to be aware of

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

Social media thrives on catchy comparisons. Jessie Inchauspé, better known as the Glucose Goddess, says she often hears doctors say that “If you don’t have diabetes, you don’t need to worry about glucose.” She responds with an analogy: “That’s like saying if you don’t have cavities, don’t bother brushing your teeth.” Meanwhile, Eric Berg, D.C. warns his audience that their health issues might well be caused by the fact that they could be consuming 25 to 30% of their daily calories from “engine lubricant,” an analogy he uses to refer to canola oil.

These analogies spread far and fast because they’re easy to understand, emotionally charged, and memorable. But what makes them powerful also makes them risky. To unpack why, we need to understand what an analogy actually does at the cognitive level. In other words, what is the purpose and what are the effects of comparing two otherwise unlike things (“X is like Y”) in the context of nutrition information?

The power, and the limits, of analogy

An analogy highlights what two things share in common. Analogies can be a great tool to expand reasoning, because by doing so, they can get you to make new connections that you might not otherwise have made, to think of an issue in a new perspective. But they can also mislead, so it’s very important to know what to look out for when you hear an analogy in the context of nutrition information.

Analogies and metaphors are a prominent object of study within the field of linguistics, precisely because of their impact on reasoning. They do two things: highlight and hide. In highlighting one similarity, an analogy may also hide other differences. That’s not inherently bad. To think productively, we often need to filter out what’s irrelevant. But when the hidden differences matter, analogies can mislead.

Let’s look at our two selected examples more closely:

Brushing your teeth ≠ managing your glucose

At first glance, the Glucose Goddess’s analogy feels intuitive and reasonable: brushing teeth is a preventive routine, and surely glucose management should be too, before conditions such as Type 2 Diabetes have time to develop. But the problems appear as soon as you examine what the analogy hides.

1. It misrepresents medical advice. Doctors who tell people without diabetes not to worry about glucose spikes are generally not saying that glucose does not matter, as the analogy implies.

Context is important, and it is exactly what is missing here. Two essential bits of context are missing here. Firstly, when doctors say that people without diabetes do not need to closely monitor their glucose levels, they say so in the context of a well-balanced diet. Secondly, this advice most likely refers to the recent trend of using continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) among people without diabetes. CGMs are life-saving devices, designed for those with diabetes. They work by measuring glucose in the extracellular fluid (rather than directly in the blood), so they are great for measuring changes to glucose in those with diabetes, where the highs and lows are more dramatic. But they may be less accurate in those with more stable blood sugar levels (source). The point of the medical advice is therefore not to dismiss glucose management, but to caution against unnecessary monitoring where it lacks evidence of benefit.

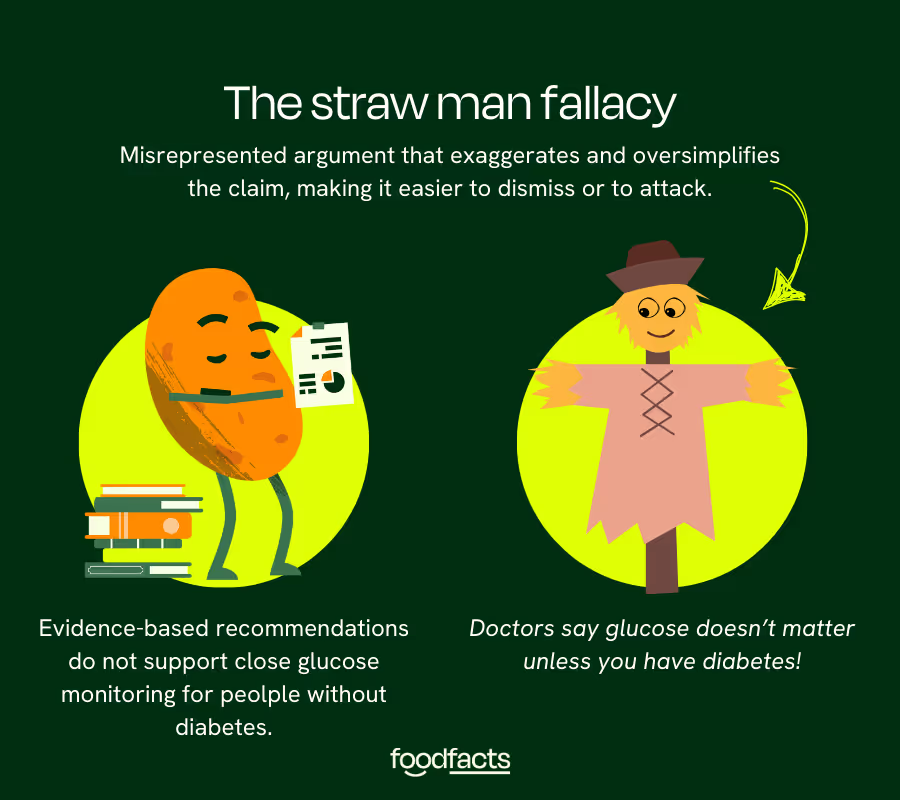

This distinction matters, because the analogy sets up a straw man. The straw man fallacy works as a distraction: while listeners are drawn to what feels like a reasonable conclusion (glucose management matters to prevent diabetes), attention is pulled away from the real premise. By subtly rephrasing doctors’ position, the analogy makes it easier to refute, presenting an appealing but misleading critique of medical advice.

This might seem like a small tweak, a mere matter of semantics. But actually, the issue isn’t so much with what is said (you should monitor your glucose!), but with how it’s communicated, in a way that undermines evidence-based dietary guidelines and the health professionals who recommend them. Because what is shared here is not merely information about the importance of glucose management, but a critique of doctors’ understanding of such issues, and of their careless advice (who would advise anyone that brushing teeth isn’t important?). This becomes especially problematic over time, as we get more and more exposed to this type of messaging.

2. It ignores normal physiology. For people without insulin resistance, glucose rises after meals and then returns to baseline. This is a normal process, not something that needs to be tracked continuously. Jessie Inchauspé has faced criticism from health professionals who argue that her approach pathologises a normal phenomenon. But this critique does not come from a careless disregard for prevention. It comes from an understanding of physiology, and from concern about the unintended consequences of encouraging people to treat everyday glucose fluctuations as harmful. Focusing on these normal responses risks fostering almost obsessive attitudes towards food, in ways that are not supported by evidence.

Encouraging everyone to track every spike risks narrowing focus to numbers while missing the broader picture of balanced eating. Eventually, this can lead to flawed choices. For example, you might adopt extreme low-carb eating to blunt every spike but end up consuming too much saturated fat, raising cardiovascular risk. While tracking glucose levels offers a tangible object of measure, there is no daily device that can provide you a number indicating how close you might be to a heart attack.

3. It hides differences in causal processes. Ultimately, the mainstream dietary advice to eat plenty of fibre, vegetables, wholegrains, and to limit ultra-processed foods already achieves the same glucose management benefits Jessie promotes, without feeding an obsessive attitude towards glucose monitoring in otherwise healthy people, which comes from construing glucose ‘spikes’, a normal scientific term, as something inherently harmful, in the same way dental cavities might be.

Cavities develop directly from bacteria producing acids that erode enamel, which happens to everyone if teeth are not cleaned. Glucose spikes after eating are not inherently harmful in people with healthy insulin sensitivity. Presenting them as equivalent processes distorts the science.

More importantly, by thinking of them as equivalent processes we can start developing negative attitudes towards food, where every bite is seen as potentially harmful. Again, this is something that happens over time, as we get more and more exposed to similar messaging. In fact, this is a common thread on social media, which often profiles this type of very direct causal relationships (“Make this simple change and see your life improve!” or on the other hand, “Eat this and see your health deteriorate!”). When we start seeing food as either danger or medicine, with no room for a middle ground, we risk fostering rigid and unhealthy eating attitudes that can lead to anxiety, guilt, and even disordered eating. Research shows that extreme perceptions of food, especially those driven by emotional associations or rigid health beliefs, can contribute to food preoccupation and bulimic tendencies, which in turn negatively affect dieting attitudes (Dicu et al., 2024). Although some “Food as Medicine” programs have shown success in improving dietary confidence and food literacy (Nara et al., 2019), there's a growing concern that oversimplified health messaging, particularly on social media, can distort this concept into a source of fear and control rather than empowerment. If taken to extremes, even well-meaning ideas about food can turn into triggers for orthorexia or other eating pathologies (Erol & Özer, 2019).

4. It downplays the difference in stakes. Cavities can be repaired. Diabetes is a systemic condition that involves insulin resistance and loss of beta-cell function. It is serious and not corrected with a single intervention. Crucially, it is not an issue that doctors take ‘lightly’.

This is why the analogy moves from catchy to misleading. It both misrepresents expert advice and creates a false equivalence between two very different biological processes.

Bottom line

From a cognitive perspective, the Glucose Goddess’ analogy works by highlighting not just the importance of prevention, but the idea of inadequate prevention. It suggests that doctors downplay glucose management in the same way it would be inadequate to say “only brush your teeth once you have cavities.” This resonates because it appeals to common sense about acting early to avoid problems, and to feelings of not being taken seriously by an overwhelmed health system.

But in doing so, the analogy takes the focus away from the fact that medical advice already promotes prevention through balanced diets and healthy eating patterns. What it distracts from is the real issue: most people do not follow dietary guidelines. And that is not a matter of laziness or ignorance. It reflects a food environment and lifestyle that make healthy choices difficult — cheap, convenient options are often the least nutritious, while time, cost, and access create major barriers.

The result is a narrative that erodes trust in experts by framing them as dismissive, while shifting attention away from the broader systemic drivers that actually explain why healthy dietary guidelines are so hard to follow in practice.

Engine lubricant ≠ canola oil

Dr. Berg’s analogy is more blunt: canola oil is cast as “engine lubricant,” invoking disgust and what feels like direct danger. Again, what’s highlighted is memorable: industrial processes, chemicals, machines. This seems to be completely at odds with healthy eating, with the focus on whole foods that are nourishing and support well-being. But while what’s highlighted is memorable, what’s hidden is critical.

The reality is that industrial rapeseed oil and culinary canola oil are genetically different. Canola is bred specifically for food use, with very low erucic acid levels that regulators monitor closely (source). Its fatty acid profile — mostly unsaturated, with some omega-3 — is considered heart-healthier than animal fats when used in moderation. In fact, it has a very similar make up to olive oil, which is often acknowledged as healthful by the same people who demonise seed oils.

But the analogy does more than spread some inaccuracies about the genetic make up of canola oil. It is grounded in the appeal to nature fallacy, and it ignores that processing isn’t inherently harmful. This distrust of anything synthetic isn’t harmless, as it could impede food innovations that might support a move towards a more sustainable food system, for example.

The analogy also overlooks the fact that many foods have applications outside of food, but the regulations tend to be very different depending on their intended use. Take corn, for example. The same crop can be milled into flour for tortillas or bread, popped into popcorn, or fermented into ethanol fuel for cars. These products follow entirely separate processes and safety standards. No one would suggest avoiding corn on the cob because corn can also be used to power an engine.

Most importantly, the analogy distracts from the role of ultra-processed foods (UPFs). Much of the canola oil we consume comes via processed snacks, baked goods, and fast food. The health issue isn’t that canola oil is “engine lubricant.” It’s that too many of our calories come from foods that are calorie-dense, fibre-poor, and loaded with sugar and salt. The analogy distracts from the real problem: dietary patterns, not one single ingredient.

Why this matters for media literacy

Analogies can clarify ideas, but they can also derail reasoning. They thrive on social media because they fit neatly into short posts, carry emotional punch, and make science sound simple. But that simplicity comes at a cost.

When you encounter an analogy online, pause and ask:

- What does it highlight?

- What does it take the focus away from? Where does the analogy stop being useful?

- Does the comparison really match the underlying processes, or is it a false equivalence?

- Does it misrepresent what experts actually say, setting up a straw man?

- Does it ignore how food is regulated, or the difference between food and non-food uses?

- Does it reduce the problem to a single ingredient, when the real issue is overall dietary patterns?

- Does it shift responsibility onto individuals while overlooking the food environment that shapes choices?

By recognising these patterns, we can appreciate analogies without losing sight of the bigger picture, of the changes that will actually make a difference to our health.

The bigger picture

Nutrition advice, stripped of drama, remains consistent: eat a variety of plant-based foods, get sufficient fibre, limit ultra-processed foods, keep added sugars and salt in check. Within that framework, occasional glucose “spikes” are normal, and cooking with canola oil is not the same as drinking from a car engine.

Analogies make nutrition sound like a battle against hidden enemies. Media literacy reminds us that the real challenge is balance.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)