Why more meat‑eaters are quietly choosing the vegan sausage roll at Greggs

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

A simple tweak to the label on Greggs’ vegan sausage roll more than doubled the share of people who picked it in an experiment – and it had nothing to do with the word “vegan”. Instead, the winning move was to highlight protein, tapping into what people care about when they are actually standing in front of a menu. This matters because nudging more of us towards plant-based options is one of the practical ways to cut food-related emissions without lecturing anyone about their lunch.

Why the word ‘vegan’ can put people off

Food marketers have known for a while that the word “vegan” can be a double‑edged sword on a label: it reassures committed vegans but can quietly switch off everyone else. Research on how plant-based foods are described has found that people often respond better to labels that focus on taste or benefits than to technical tags like “vegan” or “meat-free”. When consumers see a product as defined mainly by what it lacks – meat, dairy, eggs – they tend to expect it to be less tasty and less satisfying.

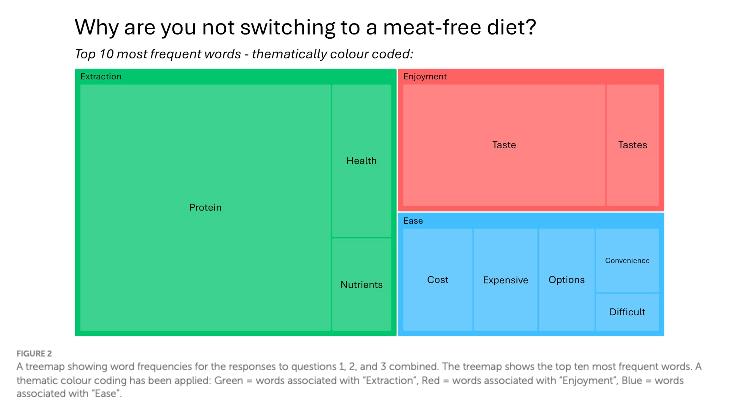

That fits with what many shoppers say when asked why they do not eat more meat‑free meals: they worry about missing out on nutrients, especially protein. In a study of 1,500 UK consumers, protein came out as the single biggest perceived barrier to going meat-free, a misconception researchers dubbed the “insufficiency illusion”. In other words, people are not necessarily hostile to plant-based food; they just assume it will not fill them up in the same way.

Inside the Greggs sausage roll experiment

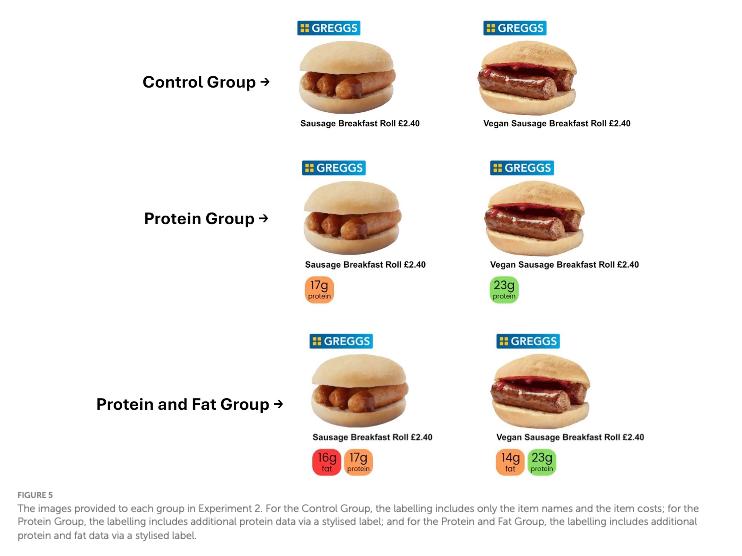

To test how labelling might get around that barrier, researchers designed an online menu experiment using just two familiar items: a regular Greggs sausage roll and a vegan sausage roll. Participants were randomly split into three groups and shown almost identical menus, each listing only those two products.

The only difference was the extra information added to the labels:

- A control menu that showed just the product names and prices

- A carbon menu that added each item’s estimated carbon footprint in brackets

- A protein menu that instead added the grams of protein in each sausage roll

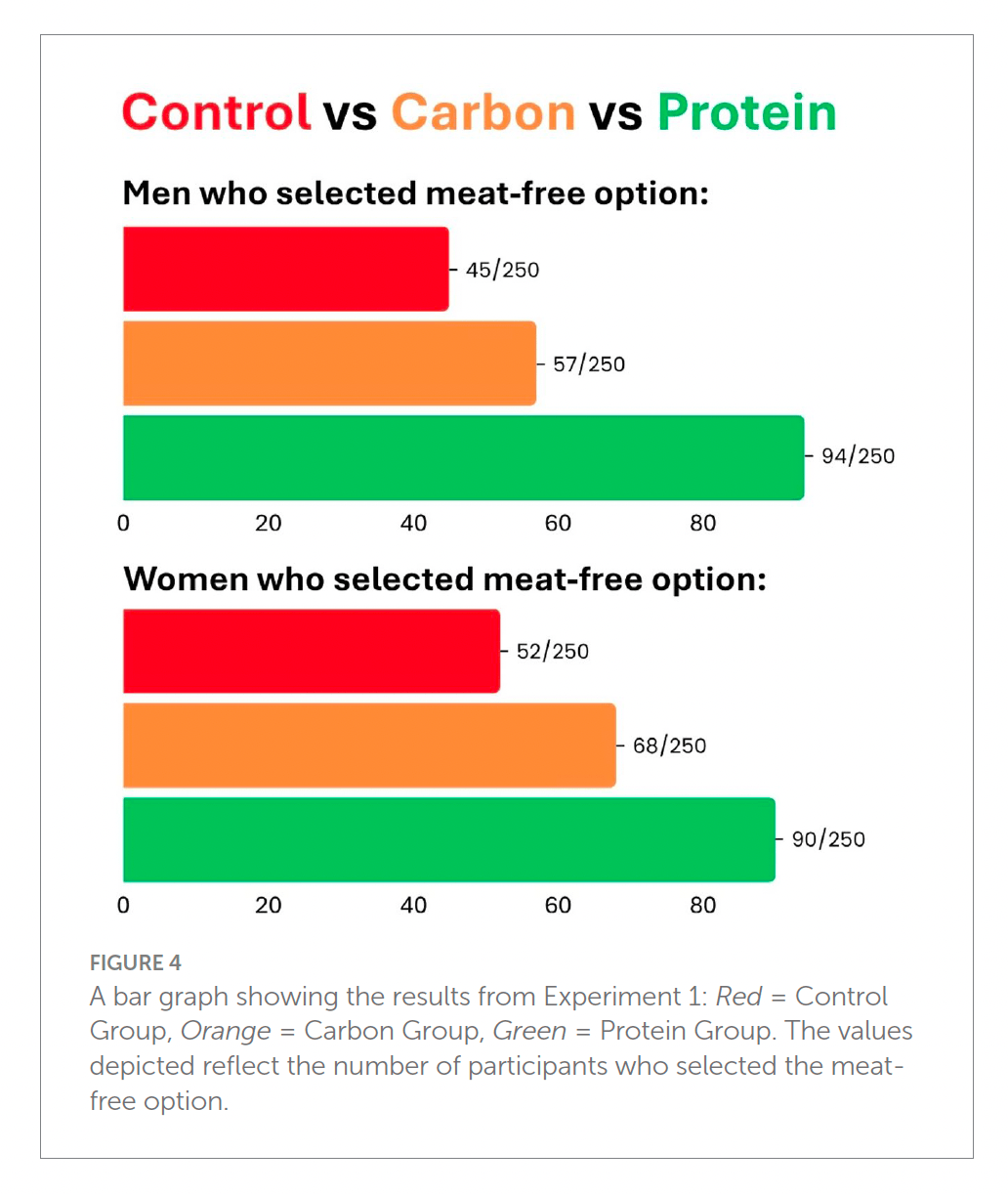

Each group included 500 people who were simply asked which sausage roll they would buy. The vegan roll was the lower‑emission and lower‑fat choice, but that information alone barely shifted behaviour: adding carbon data led to only modest increases in people choosing it.

Protein beats carbon as a nudge

The protein label was a different story. When the menu highlighted protein content, the meat‑free option suddenly became the popular choice, with the share of people picking it jumping from under a quarter in the basic menu to over half with the protein‑labelled version. That effect appeared consistently across men and women, suggesting this was not just a niche health‑nut reaction.

Crucially, the label was not making anything up. Greggs’ own nutrition data show that its vegan sausage roll contains slightly more protein per portion than the pork version, despite also being lower in fat. The research team’s point was simple: when plant‑based options genuinely stack up on nutrients, shouting about that – rather than only about carbon – can unlock a much bigger shift towards lower‑emission meals.

Reducing meat consumption with consumer insights and the nudge by proxy: the anomaly of asking, the power of protein, and illusions of insufficiency and availability Chris Macdonald. Source: Frontiers

What this means for labels – and for lunch

The Greggs study highlights a wider lesson: if the goal is to help people eat in a way that is better for the planet, it pays to start with what most shoppers already care about day to day – getting enough protein, feeling full, and enjoying their food. Carbon numbers, however important, are abstract; a “high in protein” tag speaks directly to how a sandwich or sausage roll will feel in the body.

For food businesses, that means:

- Make sure plant-based options genuinely deliver on protein and overall nutrition before trying to “nudge” people towards them.

- Use clear, honest nutrition cues – especially protein – on shelf labels and menus where they are easy to compare.

- Treat carbon labels as a complement, not the main sales pitch, unless dealing with a very climate‑engaged audience.

For anyone choosing lunch, the takeaway is reassuring: it is entirely possible to pick a plant‑based option that is lower in emissions and still hits protein goals. Greggs’ vegan sausage roll is one example of that, offering slightly more protein and fewer emissions than its pork cousin while slotting into exactly the same on‑the‑go habit. When labels highlight those concrete benefits, people show they are more than willing to eat vegan food – even if they never call themselves vegan.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)