There is no evidence that a low vitamin A diet might be beneficial for your health

Recommended daily intake of vitamin A is based on extensive scientific evidence

Health authorities recommend a certain daily intake of vitamin A based on extensive scientific evidence, rather than promoting a low vitamin A diet. In the UK, the NHS recommends a daily intake of 700 µg for men and 600 µg for women, which can be achieved through diet.

Low vitamin A, inflammation, and gut health

Contrary to the claim that a low vitamin A diet may improve inflammation and gut health, low vitamin A status may actually impair epithelial integrity and increase intestinal permeability, commonly known as "leaky gut" (source, source). This increased permeability can allow harmful substances to cross the intestinal barrier, potentially triggering immune responses and inflammation. Research suggests that vitamin A is necessary for maintaining the integrity of the gut mucosal barrier (source). Furthermore, vitamin A has been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties (source).

Caution against excessive intake

While a low vitamin A diet is not recommended, excessive intake can indeed be harmful. This principle is true for many nutrients: balance is key. Just as too little vitamin A can lead to deficiency, too much can cause toxicity.

However, caution against excessive intake is generally aimed at monitoring intake from supplements. While it is theoretically possible to consume excessive amounts of vitamin A from dietary sources, such as eating large quantities of liver, it is much more common for toxicity to result from taking high-dose supplements. A balanced diet that includes a variety of foods is unlikely to lead to excessive vitamin A intake, making it unnecessary to intentionally pursue a low Vitamin A diet.

While Burke does not recommend everyone should follow a low Vitamin A diet, the suggestion that reducing Vitamin A could reduce bloating and inflammation, or increase energy levels and mental clarity is misleading. The purpose of this video is content creation, not nutritional information. It also highlights the issue of anecdotal evidence: her personal experience of generally feeling better does not tell us anything about what it was that caused this general improvement, which could have been impacted by a multitude of factors. While her own experience cannot be disputed, science does not suggest that this is how other people will respond to following a low Vitamin A diet. In fact, the evidence seems to point in the opposite direction. Watch the following video by Dr. Idz for an in-depth analysis of the place of anecdotal evidence:

Navigating Nutrition Claims Online: Beyond Anecdotal Evidence

Navigating nutrition information online can be overwhelming. Some of the most engaging content tends to be based on anecdotes or personal experiences. However, while compelling and relatable, anecdotal evidence is not a reliable basis for making dietary changes or nutritional recommendations.

It can be overwhelming because in some cases, influencers will back up their personal stories with quotes or citations from peer-reviewed studies. But how can we tell if the study cited actually supports their argument or not?

Here are some strategies to help you evaluate such claims. Look up the study for yourself, and keep these questions in mind:

- Assess the Population Studied

- Ask: Who was the study conducted on?

- Consider: Can the results be generalised to the broader population?

- Example: A study on vitamin A supplementation in malnourished children may not apply to well-nourished adults.

- Identify the Research Question

- Ask: What exactly was being tested or reviewed?

- Consider: Does the study's focus align with the claim being made?

- Example: A study on a high-dose supplement for treating a specific condition doesn't necessarily support its use for general health.

- Examine the Balance of Evidence

- Ask: What do other studies say about this topic?

- Consider: Is there a consensus in the scientific community?

- Example: Look for systematic reviews or meta-analyses that summarise multiple studies on the issue you’re interested in.

Remember: While anecdotal evidence can be compelling, it cannot answer the crucial question: "Is this food or nutrient safe and beneficial for the general population?" For that, we need comprehensive scientific research.

Bottom Line

The promotion of a low vitamin A diet is not aligned with current nutritional science. Instead, focusing on a balanced diet that meets the recommended intake of vitamin A is the healthiest approach for most individuals. Those considering significant dietary changes should consult with healthcare professionals rather than following unsubstantiated claims from social media influencers.

Not getting enough vitamin A may cause health issues

Following the advice that a low vitamin A diet might be beneficial to support common issues like bloating or low energy levels, could lead to inadequate intake and vitamin A deficiencies. The health risks associated with vitamin A deficiency are well–documented and serious. These include:

- Xerophthalmia, potentially leading to blindness. Vitamin A deficiency is the world's leading preventable cause of childhood blindness (source).

- Increased risk of infections, including measles (source)

- Anaemia and pregnancy complications (source)

- Skin issues (source)

The most severe effects of deficiency are seen particularly among young children and pregnant women (source).

People with certain conditions, such as cystic fibrosis, Chron’s disease, celiac disease, or ulcerative colitis, may be more likely to be affected by a vitamin A deficiency (source). Additionally, vitamin A deficiency tends to be more prevalent in low-income countries, particularly in South Asia, where Vitamin A-rich foods are less accessible (source).

The promotion of a low vitamin A diet as a potentially beneficial dietary approach is not supported by scientific evidence and goes against established nutritional guidelines.

What is Vitamin A?

Vitamin A encompasses a group of fat-soluble compounds, including retinol, retinal and retinoic acid, that are naturally present in many foods. Preformed vitamin A (including retinol and retinyl esters) are found in animal sources such as dairy products, fish, and meat (it’s especially high in liver). Provitamin A carotenoids, such as beta-carotene, are precursors to vitamin A and are found in fruits and vegetables, particularly those with yellow, orange, and red colours.

It’s vital that we get enough Vitamin A from the diet as it plays several crucial roles in the body:

- Supports vision;

- Maintains immune function;

- Promotes growth and development;

- Aids in reproduction;

- Supports skin health.

Do the cited studies support Burke’s claim?

Burke provides two studies to support her claim that a low vitamin A diet might be beneficial in reducing inflammation, bloating, improving gut health and increasing energy levels.

The first is a study focused on high-dose antioxidant vitamins in head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy. It does not apply to vitamin A consumption in a balanced diet for the general population. Supplementation with beta-carotene (which gets converted to Vitamin A in the body) was interrupted during the trial, and the results mainly focused on the effects of high doses of Vitamin E. Therefore, this study does not support claims made in the video about the benefits of consuming a low vitamin A diet.

The second is the CARET trial which examined high-dose beta-carotene and vitamin A supplementation in smokers, former smokers, and asbestos-exposed workers. The study suggested that large supplemental doses of beta-carotene increased the risk of lung cancer in this specific high-risk population, but these results cannot be generalised to normal dietary intake of vitamin A in the general population. In fact, among non-smokers, other studies have shown that the risk of cancer was not similarly affected.

Burke does not mention any links to cancer in her video; however, it is a main object in the two studies she references. For those who might check out the citations provided in her caption and worry about the links between Vitamin A and cancer, it’s important to note that other studies have shown that consuming foods rich in Vitamin A could potentially decrease the risk of some cancers (source). However, there does not seem to be evidence that this benefit extends to Vitamin A-containing supplements.

As a doctor, I strongly advise against the trend of restricting vitamin A. There’s no scientific evidence that a low vitamin A diet reduces bloating, inflammation, or boosts energy, but there are well-documented risks of deficiency, including vision problems, immune dysfunction, and gut issues. Vitamin A is essential for overall health, and unnecessarily limiting it could do more harm than good. Instead of following unverified social media trends, focus on a balanced diet that meets daily needs. Extreme diets like this can be damaging—balance is key.

Promoting low vitamin A diets when there are so many public health interventions to help reduce the consequences of vitamin A deficiency is concerning. This is especially dangerous in pregnancy where low vitamin A status can result in night blindness.

Besides the idea that we can target low vitamin A specifically shows the lack of understanding of the synergistic effects of foods and the fact foods have hundreds of bioactives. Vitamin A deficiency tends to result from under nutrition and nobody should be aspiring for that!

If you’re looking for dietary advice on social media, look for people with the right credentials. Check out this guide to better understand the titles most often encountered.

In an Instagram reel posted on February 24th, Cara Burke shows a “grocery shopping haul” to “spread awareness” of “the potential benefits of a low vitamin A diet,” from reducing bloating and inflammation to increasing energy levels and mental clarity.

In this fact-check, we review the scientific evidence on low vitamin A diets to determine whether they offer potential benefits, as claimed. We also share important strategies for navigating nutrition information online, particularly when scientific studies are cited to support an influencer’s argument.

Vitamin A is an essential nutrient, critical for vision, immune function, growth, and reproduction. While excessive intake—primarily through supplements—can be harmful, deficiency can also lead to severe health issues. Current research emphasises maintaining a balanced diet that provides adequate vitamin A rather than restricting it unnecessarily.

Content creators often deliver very compelling messages, and it can be hard to know when those tips are relevant to you, or when they’re backed by science. Does the fact that they cite a study in their caption show that it’s sound advice? This fact-check gives you the tools to critically evaluate nutrition claims online and answer this question, so you can make informed decisions.

The Belle Gibson scandal: how wellness misinformation endangers public health

Following the release of Apple Cider Vinegar on Netflix, Belle Gibson’s story has made headlines again, almost ten years after she disclosed having lied about her health on social media platforms.

Known as “the woman who fooled the world,” her case highlights the profound impact of health misinformation on people’s lives, and the lack of scrutiny behind wellness influencers' platforms.

For those unfamiliar or in need of a refresher, we provide an overview of Belle’s story, followed by an analysis of its implications for the growing landscape of social media nutritional content.

The Making of a Wellness Fraudster

In 2013, Annabelle "Belle" Gibson emerged on Instagram as @healing_belle, claiming she had been diagnosed with terminal brain cancer and given just months to live. Rather than pursue conventional medical treatments like chemotherapy, Gibson claimed she was healing herself through a strict diet and alternative therapies. Her narrative of beating terminal cancer through natural remedies was compelling—it offered hope to those facing devastating diagnoses and reinforced a prevalent wellness narrative about taking control of one's health.

Gibson's social media success quickly expanded into several successful business opportunities. Her app, "The Whole Pantry," garnered 200,000 downloads in a single month. A cookbook deal followed, and Apple even flew Gibson to Silicon Valley to celebrate the launch of the Apple Watch, for which her app would be a featured offering. Throughout her rise to fame, Gibson repeatedly claimed that a significant portion of her profits would be donated to charities and the family of a child with cancer.

As her profile grew, so did her health claims. In July 2014, Gibson informed her followers that her cancer had spread to her "blood, spleen, brain, uterus and liver". Her apparent survival despite this grim prognosis only enhanced her reputation as someone who had defied medical science through the power of natural healing.

The Unraveling of a Web of Lies

In March 2015, journalists Beau Donelly and Nick Toscano from the Melbourne newspaper ‘The Age’ published an investigation that would ultimately expose Gibson's elaborate deception. Their reporting revealed that none of the five charities Gibson claimed to support had any record of receiving donations from her or The Whole Pantry, despite her public fundraisers and promises.

(Belle Gibson was interviewed and confronted with the allegations. Source: Source: 60 Minutes Australia; Netflix)

Under mounting pressure, Gibson admitted in an April 2015 interview with Women's Weekly that she had never had cancer, simply stating, "None of it's true".

The Challenges of Fact-Checking Wellness Misinformation

Gibson's case represents just one high-profile example of a much larger problem: the proliferation of health misinformation that can lead people to make dangerous decisions about their medical care.

Disinformation, Misinformation: What’s the difference and why does it matter?

Misinformation can sometimes be equated with disinformation, but the latter is a lot harder to prove. To be able to say that we are dealing with a case of disinformation, we need to show that there was an intent to deceive for personal or economic gain. This is what makes cases like Belle Gibson’s story, to a certain extent, so unique: she admitted to lying to the public, and these lies had a direct impact on the financial success of her app, The Whole Pantry.

However, most of what we encounter at Foodfacts.org is classified as MIS-information. So what’s the difference?

By definition, misinformation is not deliberate. Someone sees a post they find compelling or helpful, and shares it to help others. When this post spreads inaccurate or misleading information, it’s classified as misinformation. There is no intention to harm anyone here. But the effects are very real nonetheless.

Fact-checkers can often be criticised for calling out misinformation, when people feel that the general message behind a post was either helpful, or even justified. While no one would defend Belle Gibson’s deceptive tactics, some of the advice she shared publicly could be said to be generally helpful and health-promoting; at least that is how it was perceived then. Here’s an extract from an interview she gave on Sunrise, an Australian breakfast show:

“It’s about getting back to the fundamentals of a healthy life [...] Going back to basics and eating more of those fundamental foods, getting adequate water intake, eating more fruits and vegetables. It’s really simple and people overthink it.”

Her whole brand was built on following a nutrient-dense balanced diet, made up of whole foods. And there is certainly a lot of good in that.

So where do we draw the line? How do we know who to trust and who might be another ‘health con’?

The issue lies with the broader narrative that these posts build, and that is true whether we’re dealing with misinformation or disinformation. Consider this introduction of Belle Gibson before she gave the above interview on the show Sunrise:

“After trying the traditional [cancer] treatments, she turned to Whole Foods instead to heal herself.”

This type of statement falls directly under a growing trend on social media: talking about food as medicine.

You might ask again: what’s wrong with that? Isn’t food directly impacting our health? Isn’t promoting whole food consumption a positive step towards better health?

Yes, it is, and improving our diets would go a long way to help prevent certain chronic diseases.

But there is a fundamental difference between that previous statement, and thinking of food as medicine. There are multiple factors that impact our overall health and well-being - diet being one of them. When people talk about food as medicine, they often also imply - perhaps unwillingly - that you are in control of your health: all you have to do is eat in a certain way, and you will ‘get your health back.’ While this can be empowering for some, it can also make people who do not see changes feel immense guilt. But that is only one part of the problem.

These posts are part of a broader trend that sows distrust in authorities, and that includes health authorities. You might have encountered statements along the lines of “Doctors only treat symptoms”; “Big Pharma doesn’t want you to get better anyway, they just want to sell you their treatments. Wake up!”

This creates the perfect environment for holistic healing messages to rise in popularity. Issues arise when “food as medicine” gets combined with the rejection of medical treatments, evidence-based science, or even support from health professionals.

In this post, a wellness influencer briefly portrayed in the Netflix series criticises the show’s negativity towards holistic healing practices, which she says are unfairly demonised. I would argue that the promises of holistic healing, combined with the rejection of Western medicine and of help from health professionals, are criticised.

Protecting Public Health in the Age of Misinformation

The Netflix series might be a dramatisation, but it does raise awareness of a very real issue: the impact of certain social media narratives on people’s lives.

Social media platforms amplify this problem by design. It creates echo chambers, which can trap vulnerable individuals into bubbles where feelings of distrust can grow, and false promises might be made. This environment can eventually lead people to reject evidence-based solutions.

The show sheds light on a critical issue: the lack of background checks and accountability on social media, particularly concerning health advice. As more people turn to social media influencers for guidance, it's essential for users to discern whether these individuals are qualified to provide expert advice beyond sharing personal experiences. However, deciphering a list of unfamiliar qualifications can be daunting. Unlike the rigorous processes required to get a medical licence, social media influencers often build their platforms through charisma, an authoritative voice, and relatability—factors that drive engagement but do not necessarily ensure expertise.

Social media offers us all a platform to share our voice; to reach more people, perhaps to spread awareness of important issues; but it can also inadvertently drown the voice of experts and scientists, those who build their careers in the lab for the advancement of science, not in the public sphere.

Barbara O’Neill is an Australian alternative healthcare promoter. Complaints were raised to the New South Wales Health Care Complaints Commission following claims she made which were deemed to be dangerous, mainly regarding infant nutrition and cancer treatments. Following an investigation into her conduct and practice, Barbara O’Neill was faced with a prohibition order, stopping her from providing health services:

“The Commission is satisfied that Mrs O’Neill poses a risk to the health or safety of members of the public. The Commission therefore makes the following prohibition order:

- Mrs O’Neill is permanently prohibited from providing any health services, as defined in s4 of the Health Care Complaints Act 1993 (the Act), whether in a paid or voluntary capacity.”

Yet she continues to have significant influence through her social media platform, where she has gathered over 2 million followers from all over the world.

In ways, misinformation can be a lot harder to pinpoint than disinformation. Barbara O’Neill hasn’t lied about her qualifications. She speaks openly about her expertise stemming from lived experience. She certainly hasn’t lied about a health condition that she successfully treated ‘naturally’. Amidst videos in which she encourages people to follow a healthy lifestyle that focuses on holistic practices, eating whole foods to nourish the body rather than ultra-processed foods pushed by TV ads, she also actively discourages people from seeking medical treatments: from creams that are ‘full of chemicals’ to treat skin conditions, to advising women not to get pap smears: an evidence-based practice proven to save lives.

So let me ask again: where do we draw the line?

Once disinformation has been exposed, the person who was found to be deceptive will undoubtedly lose some influence. Misinformation can be a lot more pervasive. It might not be as extreme, but its consequences are no less real, and addressing the harm it causes can be extremely challenging. The case exposed by Netflix’s Apple Cider Vinegar should highlight why it is crucial that these issues are taken seriously.

In the meantime, people continue to turn away from evidence-based treatments through exposure to messages of distrust on social media. Others might end up developing obsessive, negative attitudes towards food, having a highly detrimental impact on their health and overall well-being. Language is powerful. Those who use large platforms to share messages of promise, from ‘getting your health back’ to ‘curing disease’, should be held accountable.

Conclusion: Beyond Belle Gibson

Belle Gibson’s story is not just about one person's deception but about systemic issues in how health information is created, shared, and consumed in the digital age. The case highlights the urgent need for better protections against health misinformation. Since her scandal broke, Australia has introduced new laws targeting people who promote misinformation about cancer treatments. However, gaps in regulation remain, particularly regarding the responsibility of digital platforms in curbing the spread of false health claims.

As Meta (formerly Facebook) scales back its fact-checking programs and health misinformation continues to proliferate online, the need for collective action becomes more urgent. This includes improved regulation of health claims, greater accountability for digital platforms, better health communication from scientific authorities, and enhanced health literacy among the public.

Psychologists and other scientists are developing strategies to combat health misinformation, including approaches known as "debunking" and "prebunking". In November 2023, the American Psychological Association released a consensus statement titled "Using Psychological Science to Understand and Fight Health Misinformation" to provide evidence-based guidance on the issue.

For individual consumers, developing critical health literacy skills is essential. This includes:

- Verifying health claims with credible sources like medical professionals and peer-reviewed research

- Being wary of miracle cure claims, especially those that position themselves against conventional medicine

- Considering the qualifications of those offering health advice

- Understanding that personal testimonials, while powerful, are not scientific evidence

- Being alert to emotional manipulation in health-related content

The dramatization of Gibson's story in "Apple Cider Vinegar" arrives at a critical moment when distinguishing health fact from fiction has never been more challenging—or more important. As we navigate an increasingly complex information landscape, the cautionary tale of Belle Gibson reminds us that when it comes to health claims, skepticism is not cynicism—it's self-protection.

The hidden power of community kitchens: tackling hunger and creating fairer food access

At Made In Hackney, a plant-based community cookery school, our mission is simple: to make good food accessible to everyone. We believe that access to nutritious, affordable food is a basic human right—not a privilege. With growing concerns about food security in the UK, we’re exploring how plant-based community kitchens can play a vital role in tackling this issue.

What Is Food Security and Why Does It Matter?

Food security means ensuring that everyone has access to sufficient, nutritious food at all times. It’s about more than just having enough to eat—it’s about having food that supports health and well-being. In recent years, food security has become a pressing issue in the UK, with rising inflation and disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic making it harder for many households to access affordable, healthy meals².

The UK Food Security Report 2024 revealed that while most households remain food secure, there has been a significant decline in the number of people who can consistently access nutritious food². This highlights an urgent need for solutions that address affordability, availability, and education around food choices.

The Role of Community Kitchens in Food Security

Plant-based community kitchens like Made In Hackney are uniquely positioned to tackle food security challenges by empowering individuals and communities with the knowledge and skills they need to make better food choices. Here’s how:

- Education on Budget-Friendly Cooking

Learning how to prepare healthy, plant-based meals on a budget is a powerful tool for improving food security. At Made In Hackney, 82% of participants in our programs reported increased knowledge of cooking on a budget¹⁰. - Promoting Sustainable Food Systems

Plant-based diets use fewer resources than animal agriculture, making them more sustainable and accessible⁶. By teaching people how to cook with plants, we can help reduce reliance on resource-intensive foods like meat and dairy⁶. - Building Community Connections

Food insecurity often goes hand-in-hand with social isolation. Plant-based community kitchens foster connection by bringing people together to share meals and learn from one another¹⁰.

Why Food Security Is About More Than Just Handouts

While government initiatives often focus on food aid as a solution to food insecurity², this approach doesn’t address the root causes of the problem. Providing handouts may offer temporary relief, but it doesn’t empower people to make informed decisions about their diets or improve long-term access to nutritious food¹².

Education is key. By teaching people how to grow their own produce, shop locally, and cook healthy meals from scratch, plant-based community kitchens can create lasting change¹³:

- Learning how to grow vegetables in urban spaces can increase access to fresh produce⁵.

- Cooking classes can dispel myths about plant-based diets being expensive or nutritionally inadequate⁶.

- Workshops on nutrition can help families make healthier choices within their budgets⁹.

The Bigger Picture: Food Security vs. Food Sovereignty

Food security is closely tied to another important concept: food sovereignty. While food security focuses on ensuring access to enough nutritious food, food sovereignty goes further by empowering communities to control their local food systems¹³. This means prioritizing local production and sustainable practices over profit-driven global supply chains¹³.

US food justice activist Karen Washington demonstrates this well when discussing the role of communities being empowered to make the changes that matter to them. She states “from small farmers and growers, to food and farm workers, a healthy food system is not just about growing healthy food but making sure that all parties along the food chain are treated fairly and humanely. Food has become a commodity, based on profits and not on people. In order for the food system to change we must face the fact that it is about sharing or giving up power.” Thus demonstrating the power of information and collective action to make change.8

In the UK, 70% of land is used for farming—yet much of it is dedicated to livestock rather than crops for human consumption⁵⁶. Shifting this balance could improve food security by making more land available for growing fruits, vegetables, and other plant-based foods that are affordable and nutritious⁴.

Globally, overproduction of meat and dairy contributes to environmental degradation and limits access to healthy foods for many communities⁶,⁷. By embracing plant-based diets and localized food systems, we can address these challenges while reducing greenhouse gas emissions and protecting animal welfare⁶.

Global Plant Kitchens: A Movement for Change

Since 2012, Made In Hackney has been at the forefront of using plant-based cooking education as a tool for change¹⁰. In 2023, we launched Global Plant Kitchens—a movement aimed at creating plant-based community kitchens worldwide³.

From Exeter in England to Lima in South America, these kitchens empower people with the skills they need to grow their own produce, cook healthy meals on a budget, and advocate for better local food systems³. Through free mentoring programs, we support projects that aim to improve both individual well-being and community resilience³.

As farmer and activist Leah Penniman puts it: “Food justice is not just about feeding the hungry; it’s about empowering communities and creating lasting change.”¹²

How You Can Help Improve Food Security

Improving food security starts with small steps that anyone can take:

- Learn how to cook plant-based meals: Join a cooking class or explore recipes online.

- Support local farmers: Shop at farmers’ markets or join a local vegetable box scheme.

- Reduce food waste: Plan your meals carefully and use leftovers creatively.

- Get involved: Volunteer at or donate to organizations like Made In Hackney that are working toward sustainable solutions.

Together, we can create a future where everyone has access to nutritious, affordable food—and where communities are empowered to take control of their own food systems.

Interested in setting up a community kitchen?

Contact Sareta Puri at sareta@madeinhackney.org for free mentoring and support.

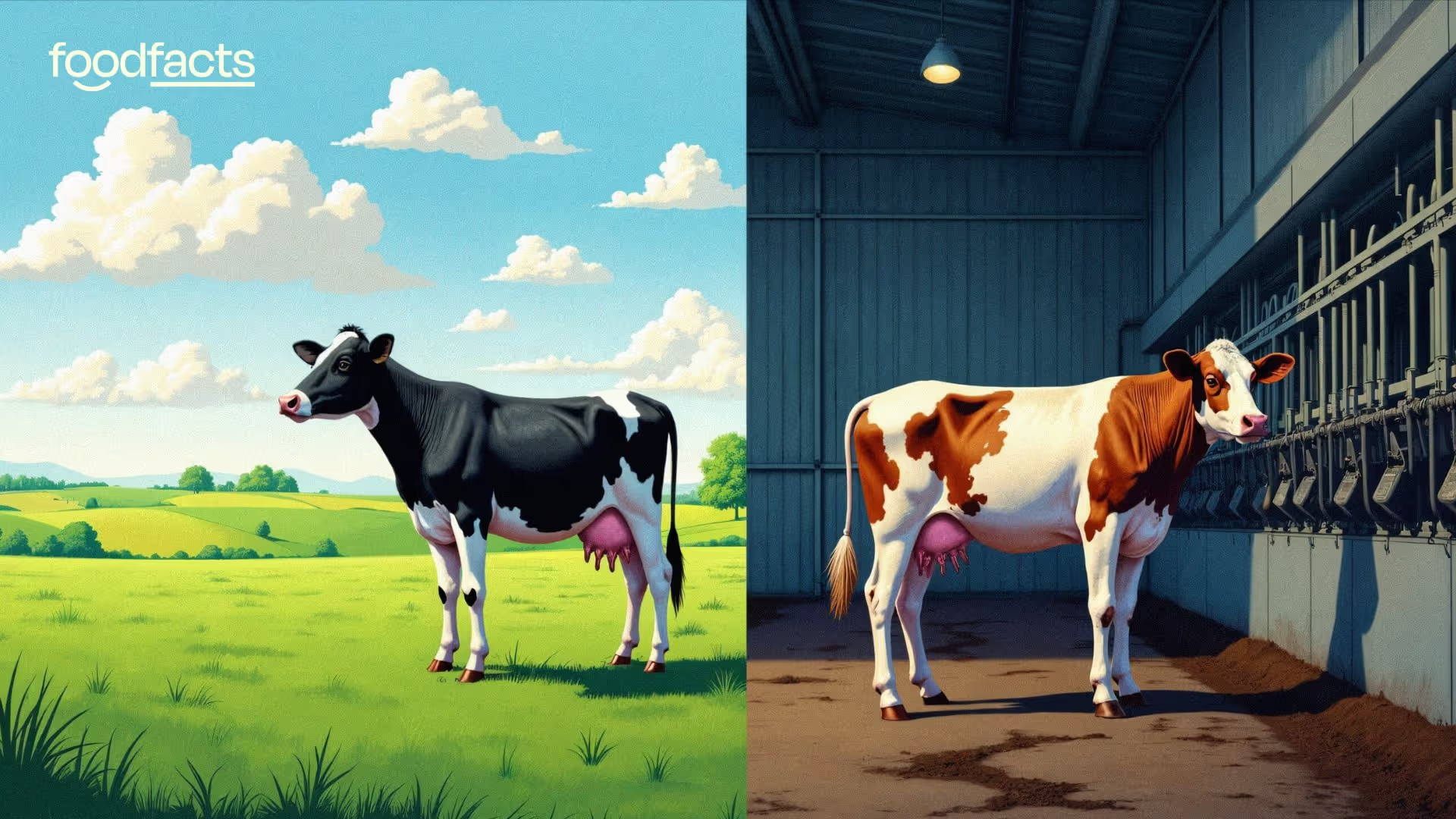

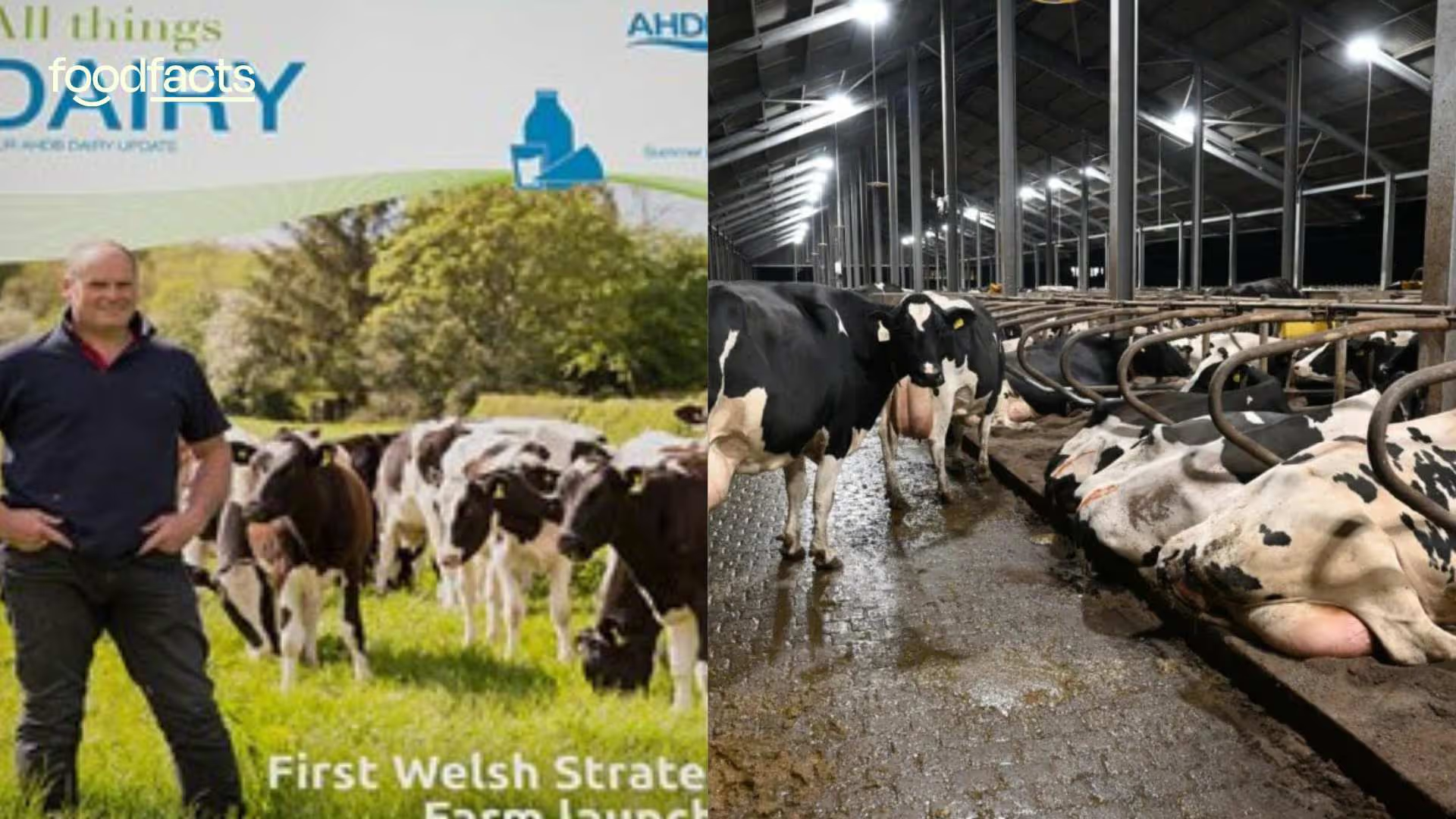

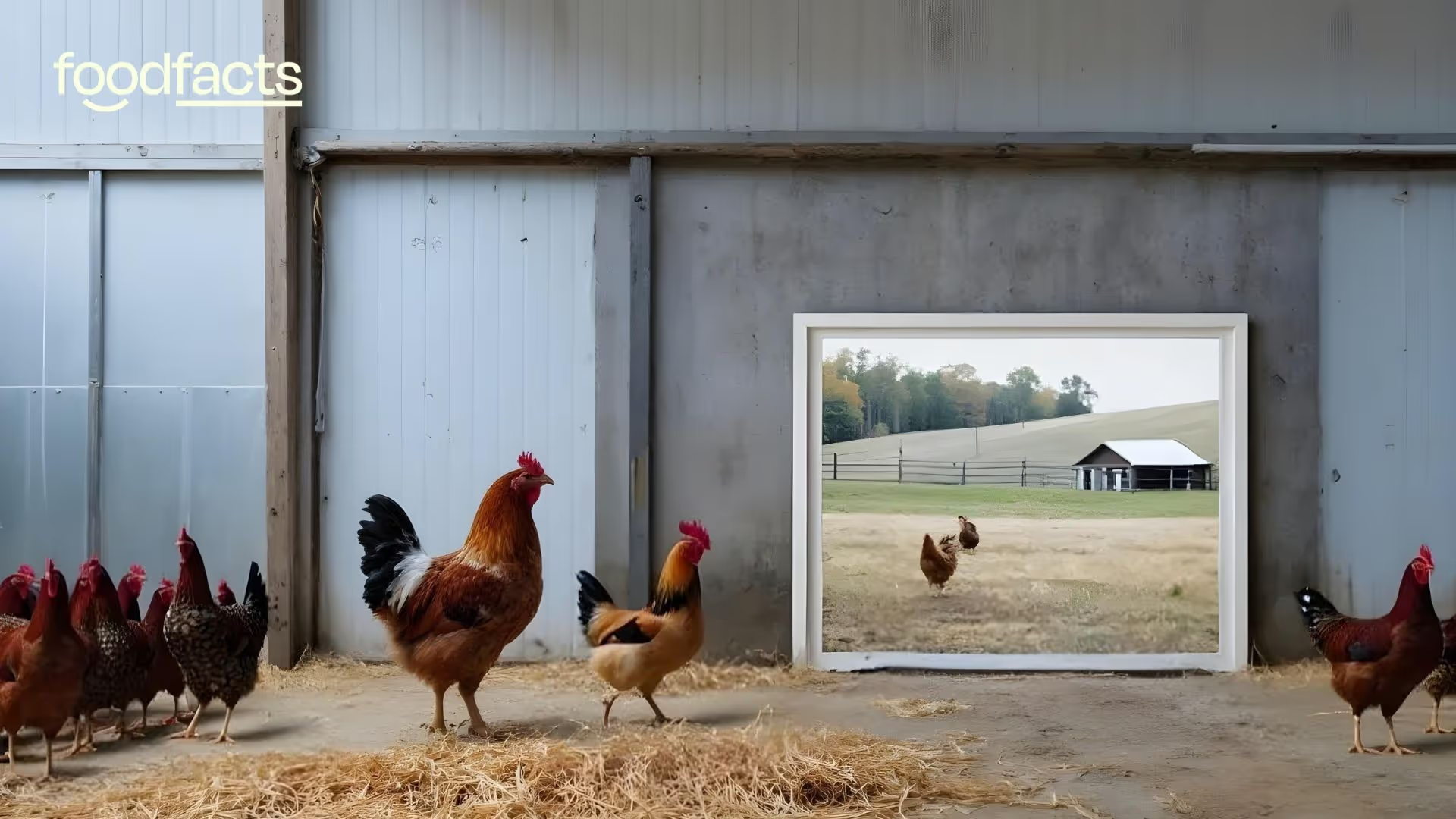

From cow to cup: the journey of dairy most consumers don't see

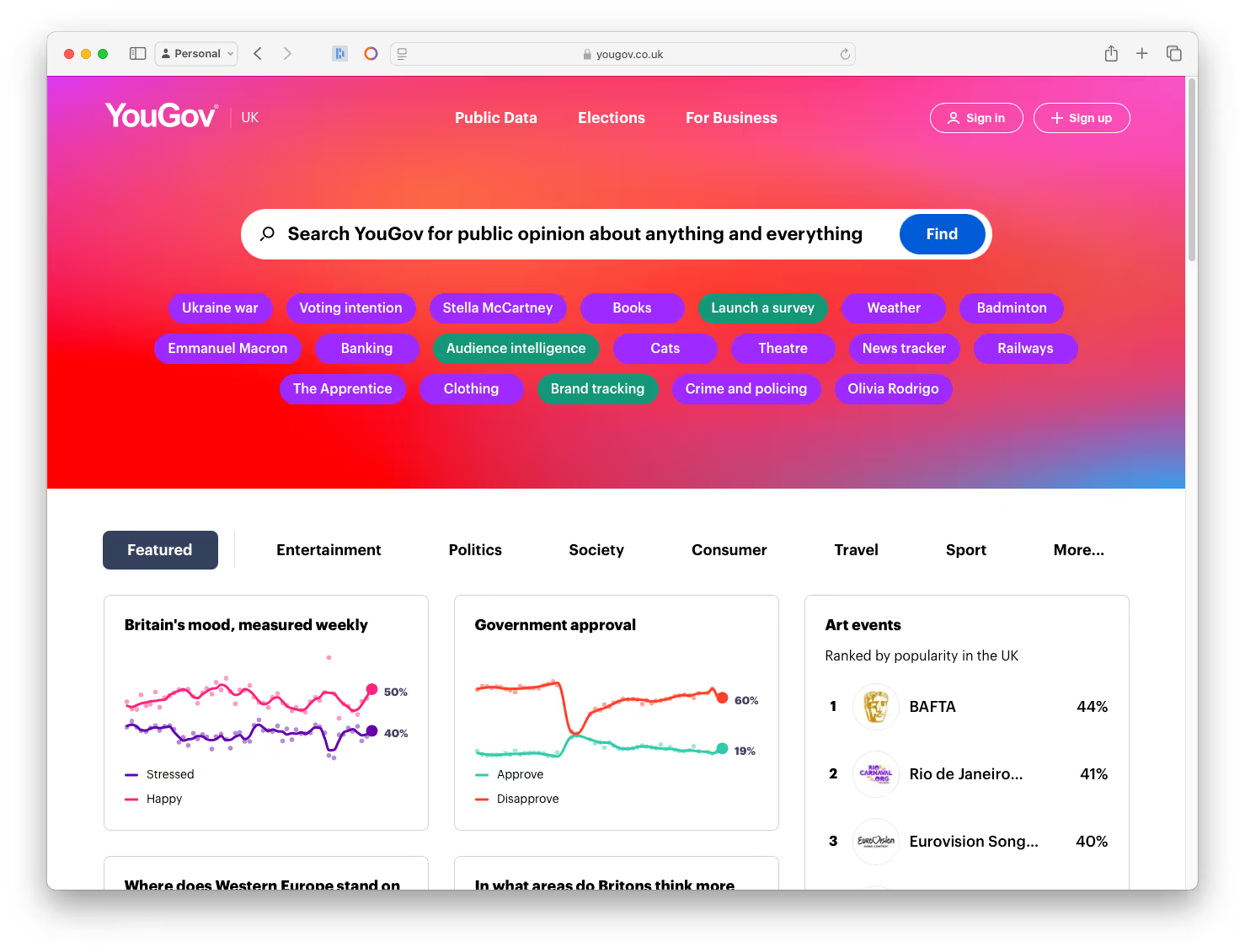

Recent research has revealed a significant knowledge gap among the British public regarding how dairy products are produced. A YouGov survey commissioned by Animal Justice Project found that more than half of UK adults were unaware that cows must be made pregnant and give birth each year to produce milk1. This disconnect between consumer understanding and the realities of food production illustrates why transparent, educational resources are essential for informed decision-making. The following deep dive aims to shed light on the dairy production process in a straightforward, factual manner to help bridge this knowledge gap. Through understanding the full journey from farm to table, consumers can make choices that align with their values and priorities.

The Biological Reality of Milk Production

Milk production is fundamentally tied to mammalian reproduction, a biological fact that applies to cows just as it does to humans. Like all female mammals, cows produce milk for the specific purpose of nourishing their young after giving birth 2,3. Their bodies begin lactating after pregnancy as a natural biological response to having offspring. This process involves hormonal changes that trigger milk production in the mammary glands once a calf is born. What many consumers don't realize is that without pregnancy and birth, there would be no milk production.

In natural settings, a cow would nurse her calf for 7-9 months while gradually reducing milk production after the initial months.2,3 However, the dairy industry requires continuous milk production to remain economically viable. To maintain this production, dairy cows are typically impregnated annually, creating a cycle where they are simultaneously producing milk from a previous pregnancy while carrying a new calf.2,3 This biological reality is one that 52% of British adults surveyed were unaware of, highlighting a fundamental gap in consumer understanding about where dairy products originate1.

From Birth to Separation: The First Days of Dairy Production

One of the most surprising findings from the YouGov survey was that 83% of people were unaware that calves are typically separated from their mothers within 24 hours of birth1. This early separation is standard practice in commercial dairy operations worldwide and represents one of the most emotionally charged aspects of milk production 6,7. The separation occurs because allowing calves to remain with their mothers would significantly reduce the amount of milk available for commercial collection.6,7

The mother-calf bond forms quickly after birth, with cows being protective and nurturing parents. Cows carry their young for approximately nine months—similar to humans—and typically form strong maternal bonds with their calves.6 7 Research has documented that both mother cows and calves show signs of distress when separated, with mothers often calling for their calves for days afterward and exhibiting searching behaviours 6,7. This separation creates significant stress for both animals, yet it remains a standard industry practice largely unknown to consumers.

As Claire Palmer, founder and director of Animal Justice Project, states: "Like human mothers, they love their babies immensely. The suffering they endure when those calves are torn away within hours of birth is unimaginable"1.

The Lifecycle of a Dairy Cow

The typical productive life of a dairy cow is remarkably shorter than their natural lifespan—a fact that 83% of survey respondents were unaware of.1 While cows can naturally live between 20-30 years, most dairy cows are sent to slaughter between 5-7 years of age when their milk production begins to decline.8,9This early culling is primarily an economic decision, as maintaining cows whose milk output has decreased becomes less profitable for dairy operations.

The lifecycle begins when female calves born into the dairy industry are raised to eventually replace their mothers in the milking herd. Starting at around 15 months of age, heifers (young female cows) are artificially inseminated for the first time, beginning their productive cycle. After giving birth, they typically undergo what the industry calls a "dry period" of about two months between lactation cycles before being reimpregnated. This continuous cycle of pregnancy, birth, lactation, and reimpregnation continues until productivity declines, at which point they enter the meat supply chain—typically as ground beef or processed meat products rather than premium cuts.

The Fate of Dairy Calves

The destiny of calves born into the dairy industry varies significantly based on their sex and the specific practices of the farm. Female calves often become replacement animals for the milking herd, continuing the cycle of dairy production. However, male calves, who cannot produce milk, present an economic challenge to dairy operations. Almost half of these calves are then absorbed by the beef industry for slaughter 3.

Male calves typically face several possible outcomes: some are raised for veal production, others are raised for beef, and in some cases, they may be killed shortly after birth if raising them is deemed uneconomical. The veal industry is directly connected to dairy production, representing one of the interconnected aspects of animal agriculture that remains obscure to many consumers. Female calves not needed for herd replacement may also enter meat production channels or, in some cases, be exported to other dairy operations.

Understanding these interconnections helps consumers recognize that dairy production doesn't exist in isolation but is deeply intertwined with other sectors of animal agriculture, creating a more complete picture of how food systems operate.

Environmental Considerations in Dairy Production

Dairy production, like all forms of agriculture, has significant environmental implications that form an important part of the ethical conversation. Modern dairy farming requires substantial resources, including land for grazing and growing feed crops, water for animals and crop irrigation, and energy for operation. The environmental footprint extends beyond the farm itself to include processing, packaging, refrigeration, and transportation.10

One of the most significant environmental concerns is greenhouse gas emissions. Dairy cows produce methane through enteric fermentation (a digestive process), and their manure releases both methane and nitrous oxide—greenhouse gases that are more potent than carbon dioxide.10 Additionally, dairy operations contribute to land use changes, water usage concerns, and potential water pollution through manure management challenges. Understanding these environmental aspects provides consumers with a more complete picture of the broader impacts of their food choices beyond the direct animal welfare considerations.

The Nutritional Reality: Dairy and Alternatives

Dairy products have traditionally been promoted as essential foods, particularly for calcium and protein. While dairy certainly contains these nutrients, nutritional science has evolved to recognize that they can be obtained from various sources. Many plant-based alternatives now offer comparable nutritional profiles, often with fortification to match key nutrients found in dairy. Understanding the nutritional facts helps consumers make informed decisions based on both ethical considerations and health needs.11, 12,14

Plant-based alternatives have expanded dramatically in recent years, with options made from soy, oats, almonds, coconut, and other plants. Each alternative offers different nutritional benefits and environmental impacts. For instance, oat milk typically has a lower environmental footprint than almond milk in terms of water usage, while soy milk often provides protein content closest to dairy milk. The survey indicated that despite knowing little about the dairy industry, one-third of Brits are still willing to have oat milk as the default option in cafes1, suggesting an openness to alternatives even without full awareness of dairy production practices.11, 12,14

Andy Shovel, co-founder of the popular plant-based meat brand THIS, recently established abitweird.org. He comments on the survey results: "As a nation, we pride ourselves in kindness towards animals: we were the first country to introduce animal protection laws, the first to ban fur farms, and god forbid someone leaves a dog in a hot car. But when it comes to the dairy industry - ignorance is bliss"1.

Transparency and Consumer Rights

Perhaps one of the most telling statistics from the YouGov survey was that only 18% of people agreed that dairy companies provide consumers with enough information about how milk and dairy products are produced1. This perceived lack of transparency highlights a fundamental issue in food systems: consumers cannot make truly informed choices without access to comprehensive information about production methods.

As CEO and founder of The Freedom Food Alliance I personally find it deeply concerning that only 18% of people feel that dairy companies provide enough information about how their products are made. This lack of transparency isn't just an oversight—it's part of a wider pattern of misinformation that allows the industry to maintain public support while concealing the routine mistreatment of cows and calves. People have the right to make informed choices about the food they consume, but that's impossible when key facts are deliberately hidden1.

Food transparency encompasses not just ingredient listings but also production methods, animal welfare standards, environmental impacts, and labor practices. The gap between consumer perception and industry reality suggests that current marketing and labeling practices may not provide sufficient information for truly informed decision-making. Addressing this transparency deficit requires both industry accountability and consumer education initiatives like this one.

When consumers understand the full context of their food choices, they can align those choices with their personal values whether those prioritize animal welfare, environmental sustainability, health considerations, or other factors. This empowerment through knowledge represents a fundamental consumer right that transcends any particular dietary choice.

Making Informed Choices

With greater awareness of dairy production practices, consumers can make decisions that better align with their personal values. For those concerned about the practices outlined in this article, numerous options exist for reducing or eliminating dairy consumption. Plant-based alternatives continue to improve in taste, texture, and nutritional value, making the transition easier than ever before.

For consumers who choose to continue including dairy in their diets, seeking products from farms with higher welfare standards may align better with their values. Options like pasture-raised dairy or products from farms with specific welfare certifications can represent a middle ground for those not ready to eliminate dairy entirely. Reading labels carefully, researching brands, and asking questions about sourcing and production methods empowers consumers to make choices consistent with their ethical perspectives.

Ultimately, the goal of providing this information is not to dictate consumer choices but to ensure those choices are made with complete awareness of what they support. Whether choosing conventional dairy, higher-welfare dairy options, or plant-based alternatives, informed decision-making represents a powerful form of consumer agency in shaping food systems.

Conclusion

The significant knowledge gap revealed by the YouGov survey illustrates how disconnected many have become from the realities of food production. In an era where transparency is increasingly valued, understanding the full journey of dairy products from farm to table allows consumers to make choices that genuinely reflect their values. The fact that more than half of British adults were unaware of fundamental aspects of dairy production suggests that more educational resources like this are needed1.

The Veganuary founder Matthew Glover commented on the survey results, saying: "These results are a serious eye-opener and it is clear that the public has no idea what happens to cows in the UK in the production of dairy products. It's shocking that more than half of Brits are not aware that cows must be forcibly impregnated each year in order to enable milk production - it's time we were enlightened and educated as part of a kinder and more sustainable society"1.

Claire Palmer, founder of Animal Justice Project, put it plainly: "In 2025, it is absurd that most people still don't realise that, just like humans, cows must be pregnant to lactate. But it's also no surprise, given the systematic disinformation the dairy industry has spread for decades"1.

As we navigate food choices in an increasingly complex system, information becomes our most valuable tool for alignment between our values and our actions. By understanding the biological necessities of milk production, the standard practices of the dairy industry, and the available alternatives, consumers can approach their food decisions with greater clarity and purpose. This knowledge doesn't prescribe any particular dietary choice, but rather ensures that whatever choice is made comes from a place of genuine understanding rather than marketing narratives or assumptions.

The conversations around food production will continue to evolve, but the foundation of those conversations must be factual information presented in accessible ways.

Through education rather than judgment, we can collectively work toward food systems that better reflect our shared values around animal welfare, environmental sustainability, and consumer rights.

Who’s killing Antarctica’s ecosystem? The dark side of krill harvesting

When people think about threats to Antarctica, they imagine melting ice sheets, starving penguins, or endangered whales. But the real culprit behind much of this destruction is a tiny, shrimp-like crustacean: Antarctic krill.

Most people have never heard of krill, yet they are the backbone of the Antarctic ecosystem. Whales, seals, penguins, and countless other species depend on krill as their primary food source. And that’s not all—krill also play a surprising role in combating climate change. By consuming carbon-rich phytoplankton and excreting it deep into the ocean, they help lock away millions of tons of carbon dioxide every year.

.avif)

But here’s the shocking part: humanity is driving krill populations to the brink of collapse. A staggering 80% of krill biomass has disappeared since the 1970s. If this continues, it could trigger an ecological chain reaction that devastates Antarctica—and accelerates global climate change.

Why Is This Happening? A Perfect Storm of Threats

Krill are facing a one-two punch from climate change and industrial fishing. Let’s break it down:

- Climate Change and Melting Ice

Krill depends on sea ice for survival. They feed on algae that grow on the underside of ice floes and use the ice as shelter from predators. As Antarctic ice disappears due to rising temperatures, krill lose their habitat and food source. Without enough krill, everything in the food web—from penguins to the great blue whale—is at risk of starvation. - Industrial Krill Fishing

If climate change weren’t bad enough, industrial fishing fleets from nations like China, Norway, and South Korea are scooping up krill by the hundreds of thousands of tons. Why? To turn them into fish feed for aquaculture, dietary supplements, and even pet food. These tiny crustaceans—vital to the planet’s health—are being crushed into powder to feed farmed salmon or sold as “omega-3 krill oil” pills for human consumption. - Greenwashing and Lax Regulations

While some krill fisheries boast “sustainability certifications,” critics have called out these claims as greenwashing. These certifications often fail to account for the broader impacts of climate change, habitat loss, and bycatch. Moreover, current fishing quotas, regulated by the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), are widely considered inadequate given the rapid decline in krill populations.

Why This Should Terrify You

Krill might not look like much, but they are the keystone of Antarctica’s ecosystem. Remove krill, and the entire Antarctic food web collapses. Imagine a Southern Ocean with no penguins, seals, or whales. This isn’t science fiction—it’s a very real possibility if industrial fishing continues unchecked.

But the implications go beyond wildlife. Krill helps mitigate climate change by trapping carbon in the deep ocean. Without them, more carbon dioxide will remain in the atmosphere, accelerating global warming. Essentially, we’re dismantling one of Earth’s natural climate defenses by destroying krill.

Inside the Industrial Fishing Machine

Industrial krill fishing is a billion-dollar industry powered by high-tech vessels and innovative harvesting methods. Companies like Aker BioMarine use advanced technologies, including krill-scouting marine drones, to efficiently locate and extract krill. These ships can pump live krill straight from the ocean, minimizing time but maximizing the catch. It’s like a vacuum cleaner for the ocean—and it’s happening in waters teeming with whales, seals, and penguins.

Sea Shepherd’s 2023 campaign exposed shocking footage of industrial trawlers operating dangerously close to whale feeding grounds. Images of whales swimming amidst massive krill fishing fleets sparked international outrage, proving that this isn’t just about crustaceans—it’s about the survival of Antarctica’s most iconic species.

Fighting Back: Operation Antarctica Defense

Amid this unfolding crisis, organizations like Sea Shepherd are fighting to protect Antarctica. Their Operation Antarctica Defense campaign has shone a spotlight on the krill fishing industry, revealing its devastating ecological consequences. In 2023, they successfully lobbied to block a proposed increase in krill fishing quotas.

Going forward, Sea Shepherd is doubling down. Their goals include:

- Advocating for expanded Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) that ban krill fishing entirely.

- Documenting industrial krill fleets and exposing their destructive practices.

- Mobilizing global outrage to push for stricter international regulations.

Their ultimate demand? A zero-catch quota for krill, ensuring that no industrial fleets exploit this vital resource.

What Needs to Change?

Saving Antarctic krill—and, by extension, Antarctica itself—requires a multi-pronged approach:

- Stronger Quotas: CCAMLR must impose much stricter limits on krill fishing or ban it outright in certain areas.

- Marine Protected Areas: Expanding no-fishing zones in the Southern Ocean is critical to safeguarding krill and the species that depend on them.

- Consumer Action: Shoppers can pressure brands and retailers to stop selling krill-based products. Boycotting krill supplements and pet food sends a clear message to the industry.

- Global Cooperation: Governments and NGOs must work together to address the root causes of krill decline, including climate change and overfishing.

What Can You Do?

You don’t need to be a marine biologist or climate scientist to help. Here’s how you can make a difference:

- Support organizations like Sea Shepherd and the Bob Brown Foundation.

- Educate yourself and others about the dangers of krill fishing.

- Demand transparency from companies that sell krill-based products.

- Advocate for policy changes that protect Antarctica’s fragile ecosystem.

The Bottom Line

Antarctica’s future is inseparable from the fate of krill. These tiny creatures are more than just a food source—they’re climate warriors, ecosystem engineers, and a lifeline for countless marine species. Allowing industrial greed to destroy them is not just reckless; it’s suicidal for the planet.

The time to act is now. Let’s stop krill fishing before it’s too late—for Antarctica, for wildlife, and for ourselves.

Don’t listen to this influencer's advice, fruit is not making you fat

Claim 1: "Eating half an apple a day causes visceral fat gain due to excess glucose."

This claim doesn’t match what science tells us about fruit and fat storage. In fact, many studies show the complete opposite, suggesting that fruits may actually help to reduce visceral fat.

Visceral fat is the fat stored in your belly around internal organs like the liver, stomach, and intestines. It’s healthy to have some visceral fat, but too of it is linked to an increased risk of conditions like heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

A study conducted in the Netherlands with over 6,600 participants found that fruit and vegetable intake was associated with less visceral and liver fat content. The authors showed that eating just 100 grams more of fruits and vegetables per day—about one small apple—is linked to 1.6 cm² less visceral fat in women.

Another article, published in 2020 in the journal Nutrients, reviewed the available high-quality evidence to conclude that fruit and vegetable intake is a chief contributor to weight loss in women. This contradicts the claim that fruit contributes to gaining visceral fat.

More evidence comes from a 2019 systematic review that found that fresh fruit consumption is likely to promote weight maintenance or modest weight loss, and is unlikely to contribute to eating too many calories and gaining excess fat or weight.

Most fruits, like apples, contain a mix of natural sugars, including glucose, fructose, and sucrose. Sucrose itself is a combination of glucose and fructose. The body primarily uses these sugars for energy before storing any excess fat, and as long as total calorie intake remains within your body’s energy needs, excess glucose from fruit is unlikely to be stored as fat. A clinical weight-loss trial comparing a high-sucrose and low-sucrose diet—both calorie-matched—found that after six weeks, participants in both groups experienced reductions in body weight, body fat, blood pressure, and blood lipids.

There is absolutely no evidence that eating half an apple a day leads to visceral fat gain. Instead, whole fruits, including apples, are likely to help you maintain a healthy weight. Learn more in the video below by Dr. Carvalho.

Claim 2: The body isn’t designed to handle large glucose hits from fruit.

This statement is misleading because whole fruit generally doesn’t cause large spikes in blood sugar, especially not those that the body can’t handle.

While fruit is relatively higher in sugar compared to other whole foods, it’s also loaded with fibre, water, antioxidants, and many other compounds. The fibre in fruit slows digestion and prevents rapid blood sugar spikes.

Your body is naturally equipped to handle the sugars in whole fruit, especially when eaten in reasonable amounts. In fact, your digestive system is designed to break down whole foods like fruits, absorbing their vitamins, minerals, fibre, and beneficial plant compounds to fuel your body and support essential functions.

In fact, we handle fruit so well, including the glucose hit, that regular fruit consumption is consistently associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, several types of cancer, and all-cause mortality.

Claim 3: Eating meat causes gluconeogenesis, turning protein into glucose, and any extra glucose becomes fat.

The claim that eating meat “causes” gluconeogenesis to produce glucose from protein is partly true but misleading, as it oversimplifies a very complex metabolic process. Saying “any extra glucose becomes fat” is also an oversimplification and inaccurate.

What is gluconeogenesis?

Gluconeogenesis is the process by which the body makes glucose from non-carbohydrate sources like amino acids when needed. This typically happens during fasting, low-carb intake, or intense exercise to maintain stable blood sugar levels.

While the body can use the amino acids from meat to “activate” gluconeogenesis, it isn’t directly triggered by protein intake and depends on tightly regulated processes. A 2013 study found that dietary protein contributes little to the production of glucose in the body through gluconeogenesis.

Frazier has previously made a similar claim, suggesting that a high percentage of the meat we eat is converted to glucose and that, therefore, we don’t need carbohydrates. Based on scientific evidence, these claims were also found to be untrue, which we explain in the video below.

Why These Claims Are Misleading

Visceral fat gain and weight gain are influenced by a complex mix of factors, including diet, lifestyle, metabolism, and genetics—not just by eating an apple. While consuming more calories than your body needs is the fundamental driver of fat gain, the reality is far more nuanced. Food quality, activity levels, and overall dietary patterns all play a role in how the body stores or burns energy.

This claim also highlights a common tactic used by some influencers: selectively distorting science to fit a particular narrative. In this case, the underlying message aligns with a restrictive, meat-heavy ideology, where anything outside that framework—such as fruit—is vilified. By oversimplifying complex nutrition science and framing certain foods as unnatural or harmful, these arguments create a compelling but misleading story.

The bottom line

Fruit is an important part of a healthy diet, and there is no evidence that it contributes to fat gain, as Frazier claims in her video.

Disclaimer

If you have a health condition that affects blood sugar regulation, such as Type 2 Diabetes, always consult your healthcare provider before making dietary changes or relying on online claims. This article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice.

Look for evidence when someone makes a claim online, reliable claims should be backed by scientific studies or data.

In a recent video, Candi Frazier aka ‘Primal Bod’ claims that consuming small amounts of fruit (e.g., half an apple daily) leads to fat accumulation and that eating meat triggers gluconeogenesis, converting protein into glucose, with "anything extra" stored as fat.

Does half an apple make you gain fat? We use the latest evidence to find out.

Whole fruits like apples are linked to better health, not obesity. Research actually links fruit consumption to lower visceral fat and improved glucose control.

Misinformation about fruit is constant and can lead people to unnecessarily fear this healthy food group, potentially pushing them toward restrictive or unbalanced diets. Understanding how the body actually processes glucose, protein, and fat can help us make informed choices without falling for diet myths.

Latest fact-checks, guides & opinion pieces

.svg)