Why do influencers keep saying that fruit makes you fat?

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

On the 20th of May 2025 Candi Frazier, known as theprimalbod on Instagram, posted a reel containing a series of claims about fruit, and its role in health. Firstly, she states fruit has been “processed through selective breeding” and is therefore “not as natural as they think”.

Comparing fruit and junk food, she questions: “Is it better than eating a Twinkie?” and concludes “if the apple is sprayed with pesticides and herbicides, probably not.”

She goes on to detail how her doctor advised her to avoid fruit during pregnancy to prevent weight gain and gestational diabetes, concluding that “Fruit does make you fat… it makes you produce insulin… the master fat storing hormone.”

But do these claims hold up to science? Let’s break it down claim by claim and examine the scientific evidence behind these statements.

Fruit is a nutrient-dense food that offers important health benefits. As part of a balanced diet it can support weight management and lower disease risk.

Nutrition misinformation spreads rapidly on social media and can significantly influence real-life dietary choices, particularly during sensitive times like pregnancy. This video relies heavily on the appeal to nature fallacy, promoting unnecessary fear around safe, healthy foods. Over time, such messages can contribute to overly restrictive diets that lack essential nutrients. Fruit, for example, is a key source of fibre, a nutrient most people under-consume, despite its vital role in digestion, metabolic health, and disease prevention.

Be cautious with absolutes like always, never, or the most dangerous; science rarely speaks in extremes.

Claim 1: “Fruit has been processed through selective breeding … It’s really not as natural as they think it is”.

Fact-Check: Let's begin by untangling the difference between processing and selective breeding, which are often confused, but are actually two very different things.

Selective breeding is ‘the intentional mating of organisms with desired traits to perpetuate those traits in subsequent generations’ (source). In simple terms, choosing plants or animals with beneficial characteristics and breeding them so that the offspring will contain those characteristics. These include better flavour, size, yield or resistance to disease.

It is not dissimilar from natural selection, just rather than the environment, it is human control that drives evolutionary changes. For thousands of years humans have used selective breeding to improve agriculture and ensure better quality and production.

While selective breeding takes place while the food is being grown, food processing refers to the mechanical or chemical changes made to the food after it has been harvested. This is generally done to help with food safety and storage as well as to enhance the flavour, texture and nutritional value of foods. Examples range from grinding grains into flour, to fermenting dairy to make yoghurt and cheese, as well as more industrial methods such as extrusion and hydrogenation.

So while it is true that selective breeding has changed fruit over time, this statement could be confusing because it conflates two distinct concepts: food processing and selective breeding.

This argument is also grounded in the appeal to nature fallacy, the idea that natural, unaltered foods are inherently better. Considering selective breeding is a technique that has been practiced for thousands of years on both plant and animal produce, by Candi’s logic almost all foods would be considered “unnatural”, which is an unhelpful way of viewing foods.

By separating foods into such rigid categories, of “natural” vs. “unnatural” or “healthy” vs. “unhealthy”, we lose important nuance and promote the belief that all food processing is harmful. In doing so, the benefits of food processing, and of selective breeding, get overlooked.

Additionally, there is no evidence that breeding plants is harmful. On the contrary, many studies have shown it can be used to improve nutritional profiles by increasing micronutrient content of certain foods. For example, using Orange Fleshed sweet potatoes to tackle Vitamin A deficiency (source, source), Quality Protein Maize, higher in essential amino acids, to address protein malnutrition (source ,source), and Iron Biofortified Beans to address iron deficiency (source).

Claim 2: “Is it better than eating a Twinkie?... it’s really just a matter of toxins… if the apple is sprayed with pesticides and herbicides, probably not.”

Fact-Check: Here Candi implies that eating an apple sprayed with pesticides and herbicides is no different from eating a twinkie.

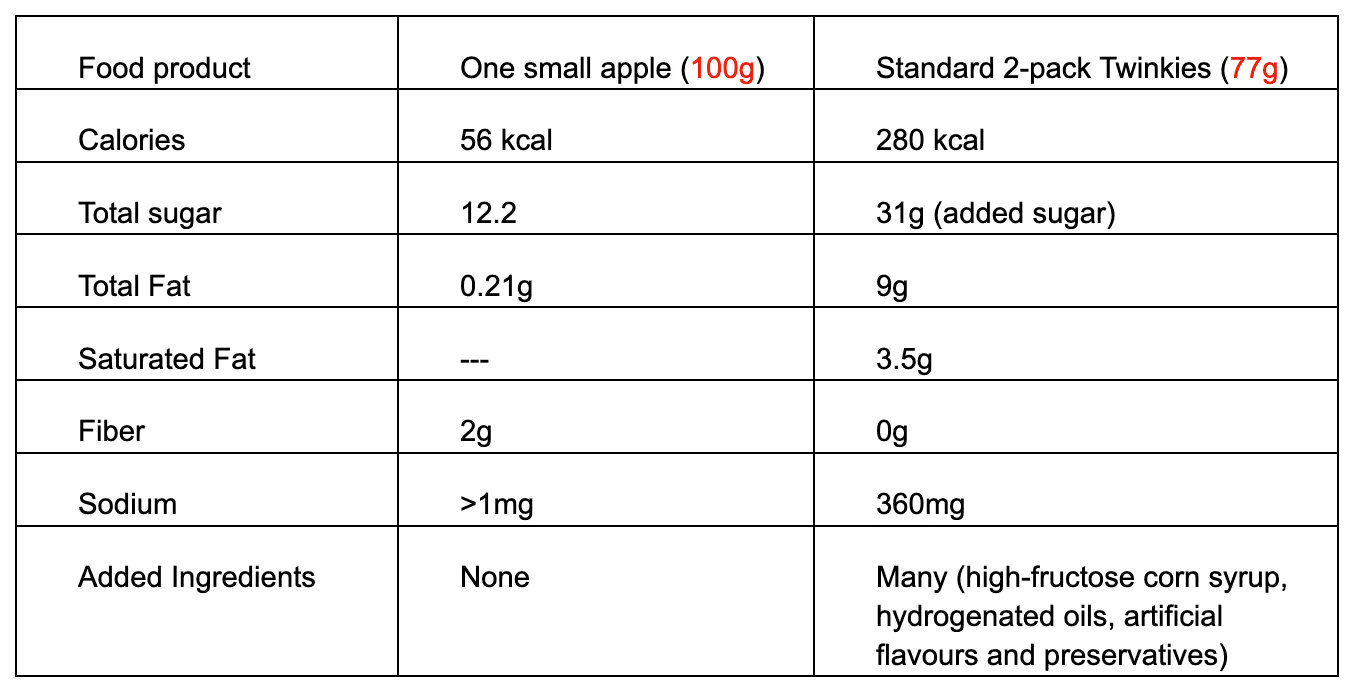

A look at the nutrition content of an apple and a twinkie tells us this is not the case.

Twinkies are a highly processed food, high in calories, saturated fat and added sugar. They have no fibre and contain many added ingredients like high-fructose corn syrup, hydrogenated oils, artificial flavours and preservatives (source).

Apples, on the other hand, are low in calories and saturated fat. They have no added sugars, and come in their natural form, unprocessed (as we’ve already established this is different from selective breeding). They are also high in fibre, vitamins, minerals and polyphenols (source).

Pesticides and herbicides are commonly used to protect crops from disease and control unwanted pests and weeds. The implication that consuming a pesticide-treated apple may be as harmful, or worse, than eating a Twinkie is highly misleading and not supported by scientific evidence.

In recent years there has been concern around the use of pesticides and herbicides, with certain pesticides being linked to diseases such as diabetes (source), metabolic syndrome (source) and some cancers (source). This is particularly in cases of chronic occupational exposure or in areas with poor regulation. However, the risk to consumers from dietary exposure is significantly lower and tightly regulated in most countries.

Large-scale assessments consistently show that pesticide residues found on fruits and vegetables are well below safety thresholds. For example, the European Food Safety Authority's 2020 report found that 94.9% of nearly 90,000 food samples were within the legally permitted maximum residue levels (MRLs), and dietary exposure was unlikely to pose a health risk to consumers (source). Similarly, a review in the UK found that only about half of food samples contained any detectable residues, and just 3.3% exceeded MRLs.

Moreover, simple practices such as washing, peeling, or cooking produce can significantly reduce any remaining residues (source).

Whilst the effects of pesticides are difficult to measure and still debated among scientists, the high amount of calories, saturated fat and sugar found in processed snacks like Twinkies are consistently associated with poor long-term health outcomes, including obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes. One umbrella review of meta analyses found ultra-processed foods were directly associated with 32 adverse health outcomes including ‘mortality, cancer, and mental, respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and metabolic health outcomes’ (source). Another mirrors these findings (source).

In contrast whole fruits like apples are consistently linked to reduced risk of chronic diseases (source).

When the benefits of eating fruits (and vegetables) are clearly outlined in scientific literature, the implication that we should avoid eating fruits just as we should avoid any type of ‘junk food’ risks promoting harmful dietary choices.

For more information on this topic, microbiologist and immunologist Dr. Andrea Love regularly shares clear evidence-based explanations related to pesticides use and residues, through her social media account and newsletter:

Claim 3: “My doctor at the time told me to not eat fruit while I was pregnant… It's gonna make you fat … you’ll end up with gestational diabetes.”

Fact-Check: Gestational diabetes (GDM) occurs when hormonal changes during pregnancy make the body’s cells less responsive to insulin, resulting in elevated blood glucose levels. It usually develops in the second or third trimester.

Large-scale meta-analyses have consistently identified the primary risk factors for GDM as older maternal age, excess weight or obesity pre-pregnancy and family history of diabetes (source, source).

One prospective study found that excessive fruit consumption in the second trimester, particularly fruits with a moderate-high glycaemic index, and tropical and citrus fruit may increase GDM risk.

Conversely, several high-quality studies have shown protective effects of consuming specific fruits against GDM. For example, one large cohort study found that women who consumed more fruits like blueberries, strawberries, blackcurrants or grapes had a 27% lower risk of GDM, with grapes alone associated with a 35% lower risk.

Further evidence from meta-analyses supports this. One meta-analysis found that total fruit consumption lowered GDM risk with a 3% reduction in risk of GDM for a 100 g/d increase in fruit consumption. Another reported a protective benefit of pre-pregnancy fruit consumption with a 5% lower risk of GDM among women who ate more fruit compared to those who consumed less.

Like all foods, fruit should be consumed as part of a varied and nutritious diet, but blaming it as one potential cause of GDM is misleading and not supported by current scientific evidence.

Claim 4: “Fruit does make you fat, it makes you produce insulin… anything that makes you produce insulin makes you fat… it’s the master fat storing hormone.”

Fact-Check: Candi’s last claim uses broad statements and overlooks the complexities of food and metabolism.

In a previous fact-check, we reviewed another claim she made about fruit consumption: that eating even half an apple a day could lead to visceral fat gain, due to excess glucose. This time she focuses more on the role of insulin.

So what actually is insulin? Insulin is an essential hormone released by the pancreas. Its main role is to regulate blood sugar levels. Following a meal, carbohydrates are broken down into glucose which then enters the bloodstream. In response insulin is released. This allows glucose to move into muscle and fat cells where it can be used for immediate energy or stored for future use.

While it's true that insulin can play a role in fat storage, attributing fat accumulation solely to insulin oversimplifies the complex interplay between hormones, diet, metabolism, and energy balance. The relationship is more nuanced, and context matters greatly.

Illustrating this point is one randomised controlled metabolic ward study, which compared two calorie- and protein-matched diets: one low in carbohydrates and one low in fat. Over the duration of the study, both groups experienced similar fat loss, suggesting total energy intake, not insulin levels, remains the primary determinant of fat change.

The claim that “anything that produces insulin makes you fat” is vastly oversimplified. Many healthy foods such as fruits, vegetables and legumes can trigger insulin release without leading to weight gain.

Fat storage occurs when calorie intake consistently exceeds calorie expenditure, not simply because a food causes insulin to rise.

The increase in insulin that follows consumption of fruit (as well as with all carbohydrate-containing foods) is a normal physiological response, not a direct path to fat gain.

In fact, many studies have shown fruit can promote weight loss and prevent obesity. A systematic review found whole, fresh fruit consumption may promote weight maintenance or modest weight loss over 3–24 weeks. It also found fruit may help reduce energy intake and offer protection against long‑term weight gain. Similarly, another meta-analysis found increased fruit intake in children and adolescents was associated with a lower prevalence of obesity when compared to a control group.

So does fruit make you fat? In simple terms, no. As part of a healthy, balanced diet, fruit is far more likely to protect against weight gain than cause it.

When it comes to fruit consumption, whole fruits are naturally rich in fibre, water, vitamins, minerals, and polyphenols, and generally low in energy density, which together may help promote satiety and support in managing overall calorie intake when consumed as part of a balanced diet. Fruit juices and dried fruits, however, are typically more concentrated in sugar and calories, and therefore may be easier to overconsume — so portion awareness is advised with these forms.'

Final Take Away

Candi’s claims about fruit misrepresent established nutritional science and may discourage the consumption of a food group consistently linked to health benefits.

Selective breeding is a natural part of agriculture and does not make fruit unhealthy. Nor does pesticide use render fruit nutritionally equivalent to ultra-processed snacks. Claims that fruit might cause gestational diabetes or fat gain are not supported by evidence, which consistently shows that fruit can help protect against both.

Overall, fruit remains a vital part of a healthy diet and plays a key role in preventing chronic disease and supporting long-term health.

We have contacted Candi Frazier and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources + Further Reading

Evidence-based information on pesticides: Dr. Andrea Love’s Newsletter

Singha et al. (2024). “Crop Improvement Strategies and Principles of Selective Breeding.”

Low et al. (2007). “A Food-Based Approach Introducing Orange-Fleshed Sweet Potatoes Increased Vitamin A Intake and Serum Retinol Concentrations in Young Children in Rural Mozambique.”

Bouis et al. (2002). “Plant Breeding: A New Tool for Fighting Micronutrient Malnutrition.”

Mertx et al. (1964). “Mutant Gene That Changes Protein Composition and Increases Lysine Content of Maize Endosperm.”

Gunaratna et al. (2010). “A meta-analysis of community-based studies on quality protein maize.”

Haas et al. (2016). “Consuming Iron Biofortified Beans Increases Iron Status in Rwandan Women after 128 Days in a Randomized Controlled Feeding Trial.”

USDA Food Tables. (2020). “Apples, red delicious, with skin, raw.”

Hostesscakes.com. (2025). “Twinkies® Snack Cake.”

Evangelou et al. (2016). “Exposure to pesticides and diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis.”

Lamat et al. (2022). “Metabolic syndrome and pesticides: A systematic review and meta-analysis.”

Merhi et al. (2007). “Occupational exposure to pesticides and risk of hematopoietic cancers: meta-analysis of case–control studies.”

Carrasco Cabrera et al. (2022). “The 2020 European Union report on pesticide residues in food.”

Mert et al. (2022). “Trends of pesticide residues in foods imported to the United Kingdom from 2000 to 2020.”

Keikotlhaile et al. (2010). “Effects of food processing on pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables: A meta-analysis approach.”

Zhang et al. (2021). “Factors Associated with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis.”

Kiani et al. (2017) “The Risk Factors of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Study.”

Huang et al. (2017). “Excessive fruit consumption during the second trimester is associated with increased likelihood of gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective study.”

Sun et al. (2021). “Specific fruit but not total fruit intake during early pregnancy is inversely associated with gestational diabetes mellitus risk: a prospective cohort study.”

Liao et al. (2023). “Fruit, vegetable, and fruit juice consumption and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis.”

Mohammadi et al. (2020). “Is there any association between fruit consumption and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus? A systematic review and meta-analysis.”

Guyenet, S.J. (2019). “Impact of Whole, Fresh Fruit Consumption on Energy Intake and Adiposity: A Systematic Review.”

Wang et al. (2024). “The estimated effect of increasing fruit interventions on controlling body weight in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis.”

Hall, K.D. et al. (2015). “Calorie for Calorie, Dietary Fat Restriction Results in More Body Fat Loss than Carbohydrate Restriction in People with Obesity.”

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)