Exposing misinformation: how influencers twist the truth on social media

Echo chambers exacerbate this effect, exposing users to similar content repeatedly, which creates the illusion of broad support for fringe ideas.

How to Recognize and Combat Deflection Tactics

Understanding deflection is essential to navigating health advice online. Danielle Shine recommends these strategies:

- Check Qualifications: Follow qualified professionals like registered dietitians and nutritionists. Nutrition science is complex, and expertise matters.

- Verify Claims: Ask for evidence. Do they cite peer-reviewed studies, or do they link to blogs and sponsored content? If no evidence exists, the claim can be dismissed, as per Hitchen’s Law: “What can be asserted without evidence can be dismissed without evidence.”

- Avoid Oversimplified Narratives: Be wary of emotionally charged claims that rely on “us versus them” language.

- Consult Experts: For tailored advice, consult a registered dietitian—your most reliable source for evidence-based nutrition.

The Broader Implications

The misuse of “misinformation” erodes trust in reliable sources, making society more vulnerable to exploitative marketing and harmful pseudoscience. Shine underscores the importance of protecting these terms so they remain tools for accountability.

A Call to Action for Informed Consumers

The fight against misinformation isn’t just about fact-checking—it’s about safeguarding trust. As consumers, you can resist deflection tactics by fostering critical thinking and prioritizing evidence-based information. By supporting credible experts and asking tough questions, you help uphold integrity and accountability in nutrition discourse.

Together, we can create a food system grounded in trust, knowledge, and informed choices.

Classic Deflection Strategies

Shine highlights a common example: exaggerated health claims, like a detox tea “curing diseases” or a diet promising rapid weight loss. When challenged for lack of evidence, influencers often frame themselves as victims, blaming “Big Pharma” or government conspiracies. By portraying the word “misinformation” as a tool of oppression, these influencers weaken public trust in science, amplifying pseudoscience instead.

Such tactics align with conspiracy narratives, reinforcing echo chambers where misinformation thrives.

Social Media’s Role in Amplification

Social media platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and Facebook accelerate misinformation. Self-proclaimed “health experts”—often without qualifications—present content as “educational” while spreading unverified claims. When debunked, they deflect by claiming suppression from “mainstream agendas.”

In today’s digital world, misinformation is a word that carries weight. Yet, as Danielle Shine, a registered dietitian and nutrition researcher, explains, some individuals are now twisting its meaning to deflect criticism. This tactic undermines accountability and creates confusion, leaving consumers unsure of whom to trust.

What Is Misinformation and Why Should You Care?

Misinformation—the unintentional dissemination of false or misleading information—often originates from well-meaning individuals, yet contributes to online deception and challenges in social media accountability.

However, research shows it spreads faster than factual content because it blends elements of truth with emotionally charged narratives. Claims about the food system, for instance, may tap into widespread discontent, making them feel relatable even when inaccurate.|

At Foodfacts.org, we emphasize that misinformation isn’t harmless. Its rapid spread can damage trust, distort consumer choices, and even harm long-term health relationships. Combating misinformation and promoting evidence-based information is critical to helping consumers make informed food choices.

But what happens when even the term misinformation becomes a tool for manipulation?

Redefining Misinformation: A Deflection Tactic

Danielle Shine has observed a worrying trend: certain health influencers in the wellness industry now weaponize the term “misinformation.” When their claims are questioned, they pivot the conversation to accusations of censorship or bias, rather than addressing the validity of their statements.

This tactic distracts from the real issue—whether their claims are accurate—and instead triggers debates about freedom of speech. Audiences become confused, focusing on victim narratives rather than factual evidence.

The term ‘misinformation’ isn’t about silencing differing opinions; it’s about identifying information that is factually incorrect or harmful. Misleading narratives around nutrition can jeopardize both human and planetary health. It’s not just about a difference of opinion, and suggesting otherwise removes accountability and makes the pursuit of knowledge no more important than storytelling.

To protect against nutrition misinformation, always check to make sure the people you follow for nutrition information are appropriately qualified. Nutrition science is complex and constantly evolving. Without a solid foundation of evidence-based nutrition knowledge and expertise, it's impossible to fully understand or accurately communicate the complexities of food and health.

When someone makes a claim about food, nutrition, or health, be sure to look for the evidence they provide to support it. Do they share websites with advertisements, blogs, or best-selling nutrition books? These are not considered credible sources of evidence-based nutrition information. If no evidence is provided, then, as per Hitchen’s Law: 'What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.'

Ultimately, the safest and most effective way to learn about nutrition online is to follow qualified nutrition professionals, such as degree-qualified registered dietitians and nutritionists. You can also verify nutrition claims on social media and determine whether they’re relevant to you and your dietary needs by consulting one-on-one with a registered dietitian, the most qualified food and nutrition expert available to you.

Oversimplified narratives on social media create an ‘us versus them’ dynamic. Influencers claim they represent the people, while health professionals are painted as profit-driven. This resonates with those disillusioned by authority, making false claims appear more trustworthy.

Always ask for evidence—if someone can’t back up their health claims with credible sources, it’s time to scroll on.

In today’s digital landscape, misinformation proliferates swiftly, intertwining partial truths with emotional narratives to seem credible. A troubling trend involves health influencers employing misinformation as a deflection tactic to evade accountability, undermining social media accountability and promoting online deception.

To combat this, nutrition expert Danielle Shine emphasizes the importance of following qualified professionals, verifying claims through evidence, and avoiding oversimplified narratives. Consumers can resist these tactics by fostering critical thinking and seeking out evidence-based information. Addressing misinformation is about more than fact-checking—it’s about safeguarding trust, accountability, and informed decision-making in the nutrition space.

Because misinformation isn’t harmless—it shapes what you eat, who you trust, and how you make decisions. Learn how to spot deflection tactics, protect yourself from harmful advice, and take back control of your nutrition choices.

“Almond milk and veggie burgers can harm the environment” Says media on new Oxford University Study; are plant-based foods worse for the environment?

Summary

The article singles out almond milk, which was the only milk that ranked worse than cow’s milk on one metric (water usage), on a per-calorie basis; it also singles out veggie bacon, which ranked worse than pork bacon on the cost metric, but was found to have a better nutritional and environmental profile than its meat counterpart. As a result, the reader is left with a skewed perspective, which comes at the expense of the big picture: yes, it is best to prioritise unprocessed sources of plant foods. But variety is also important, and the study shows that whether processed or unprocessed, replacing meat and dairy products with plant alternatives can have substantial advantages. Although the article does go on to make that distinction, the focus on the few plant alternatives which did not score as high as unprocessed products comes at the very start, following a misleading headline. Unfortunately, in a fast-paced world where people are bombarded with information, most people do not read past headlines, highlighting the importance of factual accuracy when reporting on scientific studies.

The article concludes with the need for dietary shifts, without which it might get increasingly difficult to tackle the climate crisis. However, the sensational headline reinforces misconceptions that plant-based foods might not be as environmentally friendly as we might think, which can cause confusion and potentially affect decisions.

Our rating

Misleading Potential ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Balance ⭐⭐

Factuality ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Clarity ⭐⭐⭐

The misleading rating is driven by the lack of balance provided by the article. Although the study’s findings are accurately depicted towards the end of the article, its introduction heavily focuses on the few products which did not rank as high as unprocessed products, without fully explaining which metrics the lower ratings were associated with. This imbalance could also cause some confusion among readers, as the tone of the headline and introductory statements does not quite match the article’s more balanced conclusions.

You can find out how we rate media pieces here.

We have contacted The Times and are awaiting a response.

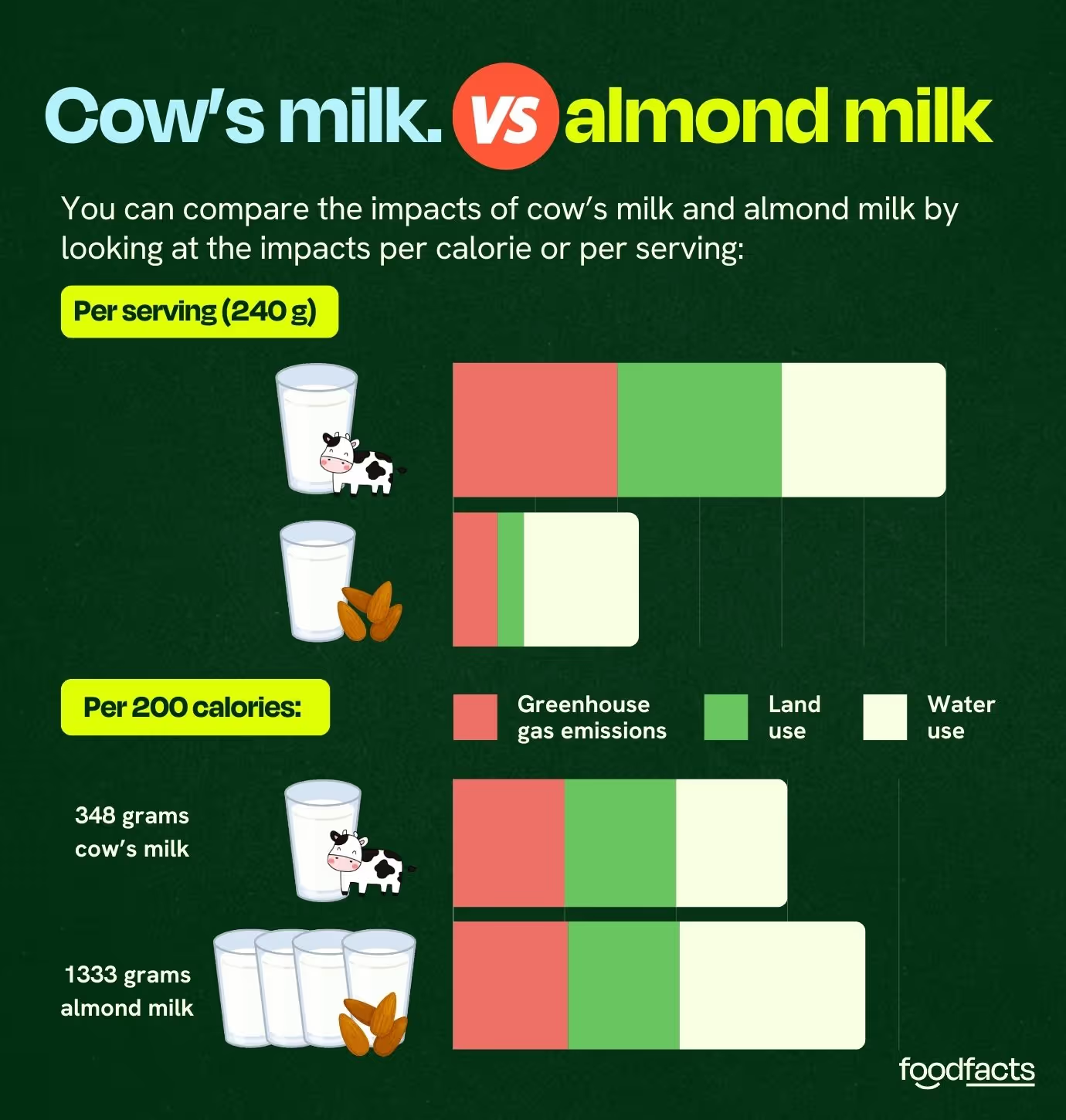

Claim 1: Almond milk was worse for the environment than cow’s milk on a per-calorie basis

Analysis: The Times article only presents the results per calorie, whereas the study includes results for the environmental impact both per serving and per calorie. It is true that per-calorie almond milk had a higher environmental impact than cow’s milk. However, per serving of milk, almond milk only had 33% of cow’s milk impact with lower greenhouse gas emissions, land use, and water use, making it better overall for the environment when considering the serving someone might consume.

If you were to replace cow’s milk with almond milk in your coffee or your breakfast, it’s unlikely you would drink 4x the amount of milk to match the calories in cow’s milk. Instead, you would probably replace it with the same serving size, in which case the almond milk has a lower environmental impact. The Times article misses out on this part of the research, presenting a misleading view by suggesting almond milk is categorically worse.

Claim 2: Some fake meat — such as veggie bacon — got a worse overall score than the pork bacon it is designed to replace.

Analysis: In the study, the researchers combined the separate scores given to each product for nutrition, mortality, greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use, and diet costs to provide each food with an overall score.

It’s true that per calorie, the overall score for pork bacon (0.57) was marginally better than the overall score for veggie bacon (0.46). However, if we look closely at the scores, this difference was driven entirely by the cost of pork vs. veggie bacon. Across every other metric, (greenhouse gas emissions, land use, nutrition, mortality, and water use) veggie bacon performed better than pork bacon.

Additionally, all meat and milk alternatives, including veggie bacon, were associated with reductions in chronic disease risk and overall mortality when compared to animal-based meats. Per serving and per calorie equivalent, veggie bacon had a lower environmental impact than pork bacon with less land use, lower greenhouse gas emissions, and less water use. However, veggie bacon had a higher cost per serving and per calorie.

Claim 3: Vegans hoping to save the planet should stick to eating beans and avoid trendy alternatives such as almond milk and lab-grown meat.

Analysis: Based on the study findings, anyone looking to maximise their environmental impact through their diet would do so by eating unprocessed plant foods like beans, which are optimal across health, environmental, and cost metrics. Swapping a serving of cow’s milk for almond milk would benefit the environment across all metrics, whereas lab-grown meat is not currently sold in the UK for human consumption, so cannot be considered a trendy alternative.

The study does not discourage the consumption of processed meat and milk alternatives like almond milk but highlights the higher water use for almonds on a per-calorie basis. Overall, they note that a range of processed and unprocessed meat and milk alternatives offer substantial environmental, health, and nutritional benefits compared to animal products. The researchers also note the risk of nutritional deficiencies for specific nutrients if consuming a more plant-based diet, such as vitamin B12. Individuals following a plant-based diet should be aware of the need to supplement with vitamin B12.

Claim 4: Popular products designed for vegans were found to be relatively bad for the climate, including oat milk, almond milk, and veggie burgers.

Analysis: The study explicitly states that processed plant-based products, including oat, almond milk and veggie burgers, offer substantial environmental benefits compared to animal-source foods, though they are less optimal than unprocessed alternatives. The media article misrepresents this nuance.

Claim 5: Tempeh is a surprising runner-up as it retains the nutritional properties of soybeans without much processing.

Analysis: This claim accurately reflects the study’s findings. Tempeh is highlighted as a strong performer due to its high nutritional value, lower environmental impact, and moderate cost.

Broader Implications

The apparently revised headline, "The vegan staples that are bad for the planet," replaced inaccuracies in the original, "The vegan staples worse than meat and dairy," to better align with the study's findings. While this adjustment improves factual accuracy, it also reflects a broader issue in sensational media reporting. Headlines aim to grab the public’s attention with shocking claims, which can distort scientific findings while reinforcing misconceptions.

Such a misleading headline is detrimental to those who read it since it can direct people away from choices that are factually better for their health, their pocket, and the environment. Even worse, it can lead to people consuming more of what could compromise their health and the environment, moreover collectively.

When reading media claims, pay close attention to context and supporting data. A single metric—like water use—can be emphasised to paint an exaggerated picture. Seek studies or fact-checks that consider the full range of factors, including greenhouse gas emissions, land use, and nutritional value, for a balanced understanding.

On December 2nd, the Times published an article titled "The vegan staples that are worse for the planet than meat or dairy," later amended to "The vegan staples that are bad for the planet." The article made several bold claims about the environmental impact of plant-based alternatives, including almond milk and veggie bacon, based on findings from a new scientific study published in the journal PNAS. This fact-check explores how accurately these claims reflect the study’s findings and whether the media's framing distorts the broader environmental narrative.

The article misrepresents the study’s overall findings by singling out products like almond milk that were found to use up more water resources. The study emphasises that replacing animal products with a variety of plant-based options can offer health, environmental, nutritional, and cost benefits.

The article’s headline illustrates the outsized influence of media framing on public perceptions of food choices. Sensationalised claims, like those suggesting that plant-based staples are worse for the planet than meat, can mislead consumers into dismissing the broader environmental benefits of reducing animal-based foods.

“The study shows” or does it? How to spot misused research on social media

1. Using studies isn’t always enough

Our guides on spotting misinformation say, “Check if they cite a reputable scientific study.” While this is a good start, the truth is that anyone can cite a study—whether it supports their point or not. The real question is how they’re using that research.

Some influencers cherry-pick studies or twist the findings to suit their narrative. They might not even look past the title. And if they’re making a big claim but only mention one study, it’s a sign they might be cherry-picking the data. So, don’t be swayed just because you see a reference to a scientific paper; take a closer look. Sometimes, research on a particular topic can have mixed results. If an influencer is only presenting one side of the evidence, they might be cherry-picking the data to support their argument while ignoring studies that disagree with their point.

For example, we recently fact-checked a post by Candi Frazier, where she claimed that grains are "depression foods," causing inflammation and, ultimately, depression. At first glance, her video seems convincing, especially when she presents a study that supposedly supports what she’s saying. However, when we took a closer look, the study actually examined a potential link between gluten and mood disorders in people with a gluten-related disorder. It did not look at the effect of grains on inflammation and depression in the general population.

Easy Step: A quick Google search can help you find other studies that show different results. If the influencer ignores or downplays contradictory findings, that’s a red flag.

2. Animal studies: mice are not humans

One common red flag is when influencers use animal studies to support their nutrition claims about human health. While these studies are often used as an initial step in biomedical research, to understand more about human health and disease, they do not provide conclusive evidence for humans. Claims based on animal studies alone lack the strength to be reliable and translated to humans.

For example, Paul Saladino has used animal-based studies to support his claims, likely because there are no robust trials supporting what he’s saying. In one video where he claims cruciferous vegetables like broccoli can be bad for health (anything from stomach issues, to thyroid health, to skin issues, or autoimmune diseases) he uses a pig study to support it. In his appearance on the Joe Rogan podcast, he claims that “LDL helps protect us against infection because it’s part of the immune system” and he uses evidence from a mouse study, which Bio Layne debunks on his blog, explaining “trying to equate a rodent knockout model with real human metabolism is ridiculous”.

How to Spot It: Animal studies are usually easy to identify from the paper title or abstract. If someone’s making a claim based on a study done in mice or other animals, be cautious—this doesn’t mean the same results will apply to humans.

3. Weak study designs: they don’t prove cause and effect

Some influencers use studies that are designed to observe patterns but can’t prove a direct cause-and-effect relationship. These weaker study designs might show correlations (things that happen together) but don’t show whether one thing causes another.

A common error is when influencers imply that a study showing correlation means causation. For example, if a study looking at nut consumption and blood pressure shows that people who eat more nuts also have lower blood pressure, that doesn’t necessarily mean eating nuts causes lower blood pressure—other factors, like exercise or genetics, could be involved.

Here are a few types of weaker study designs:

- Observational studies: These look at how variables are associated with each other (like how eating vegetables is linked to lower heart disease), but they can’t prove that one causes the other. They are useful for researchers, but they don’t give us any definite outcomes.

- Case reports: These describe individual cases or a small group of people, but they don’t give broad, reliable conclusions for larger populations.

Claims based on these kinds of studies should be taken with caution, especially if they imply definitive outcomes (like “X food will make you lose weight”). If someone says, "This food causes X," ask yourself: Is this just an association? Correlation doesn’t mean one thing caused the other. Influencers often confuse these terms to make stronger claims.

4. Stronger Study Designs: What You Can Trust More

On the flip side, some studies are much more reliable because they use rigorous methods designed to show cause and effect. If an influencer or expert cites one of these study types, the information is more likely to be trustworthy:

- Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs): Considered the gold standard, these studies randomly assign participants to different groups and compare outcomes. This helps isolate the effect of a specific diet or supplement, making it easier to determine if it actually works.

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: These review multiple studies on a specific topic, combining the results for a more comprehensive understanding. They’re often used to give a clearer picture of the overall evidence.

Also, consider the sample size. A reliable study should have a large enough sample size to make its findings meaningful. If an influencer is citing a study with only a handful of participants (for example, fewer than 30 people), this can be a red flag. Small studies are more prone to random chance influencing the results, and they often aren’t representative of the general population.

If someone references these types of studies, it’s a good sign the claim is backed by solid science.

5. Peer-reviewed research: what does that mean?

Peer review is an essential part of the scientific process. Before a study is published in a reputable journal, it goes through peer review, where other experts in the field evaluate the research. This process helps ensure that the study’s methods, analysis, and conclusions are sound.

While peer-reviewed studies are more trustworthy, it’s still important to consider the study’s quality (e.g., sample size, methodology) and whether it has been replicated by other researchers.

Red Flag: If someone cites a study that hasn’t been peer-reviewed, for example it might be a “pre-print”. Always check the source of the study to see if it went through the peer-review process.

6. Be skeptical of product-specific research

When someone is selling a product—especially supplements—they may claim it’s “backed by science.” But more often than not, the product itself hasn’t been tested. Instead, they may be citing studies on individual ingredients and then extrapolating the results to suggest their product works.

For example, Jessie Inchauspé, known as the ‘Glucose Goddess,’ promotes her anti-spike formula with bold claims like “Reduce your meal’s glucose spike by up to 40%” and “Lower fasting glucose by 8 mg/dL.” However, these claims are not based on robust clinical trials of the formula itself. Instead, they likely rely on a mix of testing on individuals—similar to a ‘case report’—combined with studies on the individual ingredients, which her website states are backed by “gold-standard, double-blind clinical trials.” This distinction is important, as these trials apply only to the ingredients, not to her specific product.

How to Check: Look at whether the product itself has been tested in clinical trials, not just the ingredients. Also, check if the research was funded by the company selling the product, which can lead to bias in how the results are presented.

7. Consider who funded the study

Sometimes, research is funded by companies with a vested interest in the results. For example, a supplement company may fund a study on the effectiveness of its own product. This doesn’t automatically mean the study is wrong, but it could introduce bias into how the results are reported or interpreted. Marion Nestle (who is not associated with Nestle the company) talks about this extensively in her book ‘Unsavory Truth’ and on her website, Food Politics.

Easy Step: Check the funding source. Studies funded by companies selling the product or diet being promoted should be taken with caution, as there may be a conflict of interest. It doesn’t mean the study is useless just because it was funded by industry.

8. Simplified conclusions from complex data

Many scientific studies are nuanced and don’t have clear, black-and-white conclusions. However, influencers might oversimplify complex findings to make them more appealing. They could say things like "Studies prove this food is bad for you," when the research may show a small effect under specific circumstances. Simplified or absolute conclusions can be a red flag that the research is being misused.

Easy Step: Look out for words like "always," "never," or "proven." Science rarely deals in absolutes, so these phrases can be an indicator that the influencer is oversimplifying the findings.

9. Was the study conducted on a population similar to you?

Some studies are conducted on very specific groups of people, like athletes, people with specific health conditions, or a certain gender or age group. If an influencer cites a study but applies it to everyone, this can be misleading. For example, if a study was conducted on elite athletes, its findings may not apply to the average person.

Again, we can look at the example of Candi Frazier and her “grains cause depression” claim. She generalised this claim to her whole audience, yet the study only found an association for people who have a gluten-related disorder, and that was still only an association rather than identifying a cause-and-effect relationship.

Easy Step: Look at the population studied. If the study participants are very different from you, the results may not apply to your situation.

10. Are the findings too good to be true?

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. If an influencer is making claims that seem too good to be true—like a product that will “melt away fat in days” or a diet that “cures” chronic diseases—then the research they’re citing may not hold up to scrutiny.

Easy Step: Be sceptical of big promises or miracle solutions. If the claim seems extreme, it’s worth looking more closely at the research behind it.

When you see nutrition advice on social media, how many times have you heard phrases like, “This is backed by science”, “studies show”, or “science shows that…”?

Many people say it, but how do you know if they’re actually using scientific research properly to support their claims?

Many influencers misuse or misinterpret studies, and it’s easy to get confused if you haven’t gone through the training, often through a health or science-related degree, to read and dissect a research paper properly.

When someone's aim is to create viral videos and not to provide useful, accurate nutrition advice, it’s less likely that they’re reading every study they cite. In fact, this is pretty clear when we start to look at how many influencers cite a study, only for it to say something completely opposite to what they're claiming.

Sometimes it’s not enough to just check whether someone is citing research; you need to understand how they’re using it. Here are some key ways to tell if an influencer or expert is using scientific research appropriately or misleadingly.

Elon Musk claims animal agriculture makes no difference to global warming

Claim 1: Animal agriculture has no material effect on climate change.

Animal agriculture has a measurable and significant impact on global greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has highlighted animal agriculture’s role in climate change. Agriculture as a whole is responsible for about 26% of global GHG emissions, with more than half of these emissions coming from animal-based food production. These emissions stem from various processes, including land use changes, feed production, and water consumption—each contributing to significant environmental impacts.

One major contributor to these emissions is methane from livestock digestion and manure management. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, and although it lingers in the atmosphere for a shorter period than carbon dioxide, it has more than 80 times the warming potential of CO₂ over a 20-year period.

Furthermore, the environmental impact of animal agriculture extends beyond emissions. Deforestation for grazing land and soy production for animal feed has led to widespread habitat loss, particularly in regions like the Amazon rainforest, where over 800 million trees were cut down within six years to meet the demand for Brazilian beef. These environmental changes reduce the planet’s carbon-sequestering capabilities, exacerbating climate change impacts.

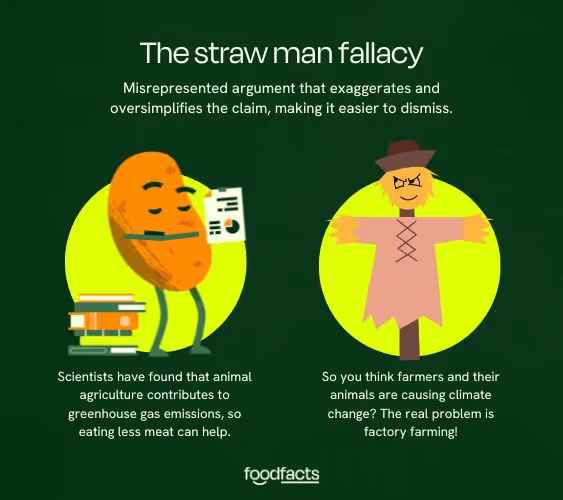

Using a Straw Man Fallacy to Stir Engagement

Musk and Rogan’s discussion creates a straw man fallacy by suggesting that environmental advocates claim animal agriculture is the “main driver” of climate change, an argument which is then criticised for being exaggerated and false. In reality, scientists recognise fossil fuels as the largest contributor, and no credible source claims that animal agriculture is the primary cause of global warming. However, environmental scientists emphasise that reducing animal agriculture’s share of emissions is an essential step for achieving climate goals. By misrepresenting the argument, the podcast hosts downplay the actual impact of meat production, making a serious environmental issue seem exaggerated or irrelevant when it’s actually a key area for action. Instead, the argument that animal agriculture has no ‘material effect’ on climate change implies that dietary changes will achieve nothing to limit global warming and its consequences.

Claim 2: There’s no way to measure the impact animals have on global warming.

This is a popular claim on social media, which tends to depict environmentalists as detached from the reality of what goes on in farms. But contrary to Musk's claim, scientists have been measuring the impact of animal agriculture on global warming for decades. Researchers use several methods to assess the environmental footprint of animal farming, including life cycle assessments (LCAs) that measure emissions from every stage of production, from land and water use to the release of methane and nitrous oxide during livestock digestion and waste decomposition. The impact of animal agriculture is assessed using factors such as:

- Greenhouse gas emissions (methane, CO₂, nitrous oxide)

- Land and water use

- Biodiversity impact

- Eutrophication (pollution of water bodies due to excessive nutrients)

Trying to measure the climate impact of a diet is difficult, because scenarios don’t always reflect what people actually eat or differences in how food is produced. However, researchers from the University of Oxford used data from 38,000 farms in 119 countries, and analysed the diets of 55,504 people in the UK to measure this. They found that greenhouse gas emissions, land use, and water use were all higher for diets containing more animal products. They concluded that despite variations in production methods and food origin, the high environmental impact of animal agriculture is clear.

Claim 3: Regenerative animal farming is carbon-neutral.

Joe Rogan adds that factory farming is the real issue, stating that regenerative farming is carbon-neutral. While regenerative practices, like managed grazing, can enhance soil health and carbon sequestration, the overall effect is limited. A review of 300 papers found that only a fraction of the emissions produced by animals – through burping and defecating – can be offset through carbon sequestration. Additionally, regenerative farming requires significantly more land—up to 2.5 times more than conventional beef production. This makes it unrealistic to switch globally to regenerative practices and keep consuming and producing current levels of animal products. In terms of land use, regenerative farming might actually be more harmful to the environment.

Why Reducing Meat Consumption Matters

The environmental impact of the meat we consume is real. While global statistics and emissions' measurements may seem removed from daily life, they translate directly to the food on our plates. The recommendation to reduce meat consumption isn’t just theoretical; it’s grounded in the fact that producing meat requires vast resources. Each piece of meat involves land, water, feed, and significant emissions that drive environmental degradation. Favouring local or sustainably raised meat can reduce some impacts, but meaningful benefits can only be achieved if paired with an overall reduction in meat consumption.

On the other hand, if everyone adopted high-meat diets like the Carnivore Diet—frequently discussed by Joe Rogan—the demand for livestock would skyrocket, requiring even more animals, land, and resources. This would multiply the emissions and lead to greater deforestation, especially if regenerative or grass-fed practices are prioritised, as they require more land to produce the same amount of meat.

We have contacted Joe Rogan and are awaiting a response.

For accurate information on sustainability issues, rely on evidence-based sources that consider the full environmental impact, including emissions, resource use, and biodiversity.

During a recent interview on The Joe Rogan Experience, Elon Musk made claims about animal agriculture and its impact on climate change. He argued that animal agriculture has "no material effect on climate change," and Rogan suggested that the idea of animal farming as a major environmental contributor is simply “propaganda.”

Animal farming is a well-established contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, and resource use.

Understanding the full environmental impact of meat production is not easy, because it involves a myriad of factors which can have a knock-down effect on ecosystems, greenhouse gas emissions, water usage, deforestation, and biodiversity loss. Claims on social media often simplify this complexity by portraying direct causal relationships, such as “cows don’t cause climate change.” But if we overlook the role of animal agriculture, we risk missing an opportunity to address a major climate challenge.

Milk down the drain: some social media users protest over Arla’s methane-reducing additive Bovaer

Videos have emerged on social media showing some UK users pouring milk down sinks and toilets in protest against Arla Foods’ use of Bovaer, a methane-reducing additive in cow feed. While the scale of these protests is unclear, they have sparked conversations about the dairy industry’s environmental impact and the use of new technologies like Bovaer. While the addition the ingredients is framed as a step toward addressing the climate crisis, it raises larger questions about the dairy industry’s environmental impact and whether the focus on mitigating methane emissions is merely a band-aid solution for a much bigger problem.

What Is Bovaer, and Why Are People Concerned?

Bovaer, developed by DSM-Firmenich, is a feed additive that reduces methane emissions from cows by about 27% in feedlot settings only, as it's unclear of its effectiveness over the lifespan (including when the on pasture). Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with a global warming potential 25 times greater than carbon dioxide over a 100-year period. Livestock farming is responsible for anywhere from 15-20% of all direct human-induced planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions, with methane from cow digestion being a major contributor. This doesn't include the enormous opportunities to sequestered carbon on freed up land used by animal agriculture.

Despite its environmental promise, the additive has sparked backlash. Protesters argue that instead of investing in technologies like Bovaer, the dairy industry should focus on reducing the number of cows and scaling back dairy production altogether. This sentiment is fueled by broader concerns about the dairy industry’s environmental toll, including its impact on land, water, and biodiversity.

@i_do_things Asda Arla Milk Boycott #arla #billgates #bovaer #milk #dairy #asda ♬ original sound - Things I Do

Is Bovaer Safe?

This is very early stages for this research and bold claims of environmental improvement are already being exaggerated, but Bovaer essentially works by suppressing a methane-producing enzyme in cows’ digestive systems. With similar feed additives though, cows gut microbes adapted after a short period of time leading back to baseline high methane emissions.

Regulatory bodies like the UK Food Standards Agency (FSA) and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) have reviewed and approved the additive, confirming its safety for both livestock and humans consuming dairy products from treated cows. Studies show that Bovaer breaks down entirely in the cow’s digestive system, leaving no residues in milk or meat.

However, consumer mistrust remains high, driven by fears of long-term health impacts and a lack of transparent communication from the industry. Social media misinformation has further compounded skepticism, with some labeling the additive “toxic” despite evidence to the contrary.

The Bigger Picture: The Environmental Toll of Dairy

While methane-reducing technologies like Bovaer claims to tackle one aspect of the dairy industry’s environmental footprint, they fail to address its broader ecological impact. Producing a single liter of cow’s milk requires approximately 1,000 liters of water, a staggering statistic that underscores the resource intensity of dairy farming.

Additionally, dairy farming contributes to:

• Waterway Pollution: Manure runoff and fertilizers from dairy farms often contaminate rivers and lakes, leading to algal blooms and biodiversity loss.

• Deforestation and Land Use: Vast tracts of land are cleare

d for growing feed crops, resulting in habitat destruction and increased carbon emissions.

• High Carbon Footprint: Beyond methane, dairy farming releases significant amounts of carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide, further exacerbating climate change.

These issues highlight the need for systemic changes, such as reducing global dairy herd sizes and transitioning to more sustainable alternatives.

Why Focus on Cutting Herd Sizes?

While innovations like Bovaer aim to make dairy farming less harmful, they don’t address the core issue: the sheer scale of the industry. According to environmental experts, reducing the number of cows is one of the most effective ways to cut emissions and lessen the industry’s strain on natural resources.

Alternatives like plant-based milks, which require fewer resources and emit significantly less carbon, are becoming increasingly popular. For example, producing oat milk requires 80% less water and emits 70% less carbon dioxide than cow’s milk. By promoting these alternatives, the global food system can take meaningful steps toward sustainability.

Are Dairy Alternatives the Future?

The rise of plant-based milks offers a glimpse into a more sustainable future. Oat, almond, soy, and pea milks are gaining traction as viable replacements for traditional dairy, offering environmental benefits without compromising on taste or nutrition. Beyond personal dietary choices, systemic support for plant-based alternatives—through subsidies and public education—could accelerate the transition away from resource-intensive dairy farming.

The Path Forward

The milk-pouring protests signal growing public frustration with the dairy industry’s environmental impact and its reliance on high-tech fixes like Bovaer. While reducing methane emissions is important, a larger conversation is needed about the future of food production and the role of animal agriculture in a climate-conscious world.

Educating consumers about the true cost of dairy—on the planet, waterways, and biodiversity—empowers them to make informed choices. Whether it’s cutting back on dairy consumption, supporting plant-based alternatives, or advocating for systemic reforms, individuals have the power to drive change in the food system.

Updated 5th December 2024

The headline was updated to specify the fact that the trending of milk pouring is not necessarily wide spread and is likely isolated to a small subset of social media creators. Without further evidence there is no clear evidence that this is a nation wide protest.

Are ‘best before’ dates necessary? Understanding food labels and reducing waste

What Are ‘Best Before’ Dates?

‘Best before’ dates feature on most food packaging. They indicate the timeframe in which each product should be consumed for peak taste, texture, and nutrient density. In contrast to ‘use by’ dates, which are featured on highly perishable foods and are designed for food safety, best before dates are simply guidelines for an optimal consumer experience.

By law, pre-packaged food must feature durability indications like best before dates and any necessary storage instructions. The UK’s Food Standards Agency (FSA) confirms that while use-by dates relate to food safety, best-before dates simply relate to quality.

However, many people continue to find the differences between sell-by, use-by, and best-before dates confusing. This results in wasted food. To avoid wasting food or consuming spoiled ingredients, some people say they simply use common sense, confirming with a visual and olfactory inspection whether something is good to eat or not.

Until relatively recently, this common sense approach was the only way to avoid spoiled food. Best before dates were launched to supermarket shelves by British retailer Marks & Spencer in the 1970s, after several years of use behind-the-scenes in stock rooms. While much of the industry maintains that best before dates are still helpful, anti-waste campaigners argue that they encourage people to throw out still-fresh foods and shop more.

Speaking to the BBC, Caitlin Shepherd of the campaign group This Is Rubbish, said that the main reason for best before dates is to protect retailers from potential litigation. "It's a symptom of our over-sanitized relationship with food," she added. “The best way to tell whether something is still fresh is by having a sniff, having a little taste.”

Food Waste And Best Before Dates

Confusion over food labeling and best before dates undeniably contributes to the growing global food waste problem. A 2021 survey found that less than half of US adults could describe what a “use by” label meant, even though the majority of people rely on them.

These results are borne out in other research, too. A 2023 report by the US’s Congressional Research Service found that labeling confusion causes at least seven percent of food waste. Since the US wastes 60 million tons of food annually (up to 40 percent of the total supply), labeling confusion causes approximately 4.2 million tons of food waste every year.

Globally, around 1.3 billion tons - one-third of all produced food - is lost or wasted per year, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The FAO estimates that this wasted food could feed around 1.26 billion food-insecure people.

This food waste also means that the water, land, labor, and billions of animal lives used in its production were wasted. And since most food waste ends up decomposing in landfills, where it produces the greenhouse gas (GHG) methane, the entire production-to-decomposition lifecycle of wasted food is extremely, unnecessarily high impact.

In fact, up to 10 percent of the planet’s total greenhouse gas equivalent (GHGe) emissions come from food waste. According to the environmental action NGO WRAP, if wasted food were a country, it would be the world’s largest GHG emitter after China and the US.

Solutions To Labeling-Related Food Waste

Since consumer confusion over best before dates is a key factor in food waste, there are several ways to promote a better understanding of these systems, including improving food education and standardizing labels industry-wide to make them more coherent.

In October, a new California law made it compulsory for producers to standardize the language on all food packaging sold within the state, per Retail Wire. If the law demonstrably reduces food waste, it’s possible that other states will introduce similar legislation, and companies forced to comply will simply update packaging across their entire ranges.

Speaking to the Washington Post, the Natural Resources Defense Council’s senior specialist Andrea Collins noted that some people are still “prematurely tossing food that could be really nourishing,” such as cereal and other long-lived staples. She described many best before dates as simply manufacturers’ “best guess at quality.”

Several companies are taking the initiative by updating labeling to reflect this. The yogurt brand Danone, which is a member of Too Good To Go’s “Look, Smell, Taste, Don’t Waste” campaign, has swapped ‘use by’ for ‘best before’ on its various dairy and nondairy products.

Meanwhile, in the UK, Asda, Morrisons, Marks & Spencer, and Waitrose have all scrapped best before dates on certain fresh fruit, veg, and milk products. Sainsbury’s has implemented similar measures, and swapped in text that reads “no date helps reduce waste.” Once again, the message is for consumers to decide for themselves if food is safe to eat or not.

Key Takeaways

While many people have become reliant on best before dates on food packaging, a lack of standardization, clarity, and consumer education around labeling is contributing to the problem of global food waste. Addressing these issues altogether will be critical in mitigating waste and all of the intersecting environmental and social issues.

As shown in California, legislative intervention may be the simplest way to ensure standardization and updated language when it comes to best before and use by dates.

While re-evaluating the necessity and impact of dates in food packaging can almost certainly help create a more sustainable food system, it’s important to note that around 13 percent of all food waste happens between harvest and retail, i.e. at a production level.

Encouraging the donation of surplus food to charities and local food banks can help to mitigate this. However, that model isn’t sustainable either, not without seriously reducing production, likely by incentivizing efficiency at both production and retail levels.

Greater Lincolnshire Food Partnership coordinator Laura Stratford told Circular Online that while everyone does have a responsibility to mitigate food waste, “lecturing individuals on wasting food” isn’t going to fix a model predicated on overproduction and overconsumption.

Instead, the global food industry must be overhauled at every level, simultaneously, if food waste is to be effectively mitigated, with labeling making up just one small part of the whole.

Latest fact-checks, guides & opinion pieces

.svg)