No, fibre isn’t useless – why Dr Ede's comments on DOAC are wrong

In the podcast, Ede creates a false and potentially harmful narrative that humans don’t need fibre in their diet. Fibre is essential for healthy bowel movements, reducing colorectal cancer risk, and supporting overall health.

We have contacted Dr Ede and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

Quotes from the podcast have been phrased to remove filler words, making it easier to read, without changing the content.

The information provided here is for general information purposes only, and should not be considered medical advice. If you have Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes or any condition requiring careful blood sugar monitoring, please consult your healthcare provider for personalised guidance tailored to your specific needs.

Fibre is essential for butyrate and a ketogenic diet isn’t a substitute.

The fourth claim Ede makes is that we don’t need fibre to provide butryate.

“There are quite a few papers on this claiming that we need fibre because we need to feed our cells butyrate, which is a breakdown product of fibre. But if you think about what a ketone is, it’s beta-hydroxybutyrate, which feeds the intestinal cells just as well, so you don't need to eat fibre to feed your cells butyrate. If you think that the cells need butyrate then you can get it from a ketogenic diet.”

Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) produced when gut bacteria ferment dietary fibre. It serves as a primary energy source for the cells lining the gut, playing a crucial role in gut barrier integrity, inflammation regulation, and overall digestive health. While beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB)—a ketone body produced during ketosis—shares some structural similarities with butyrate, they are not interchangeable in function.

BHB can serve as an alternative energy source during low carbohydrate intake, but research suggests it does not replicate butyrate’s role in maintaining colon health. Butyrate has specific anti-inflammatory and gut-protective effects that BHB does not fully replace. Fibre is essential for supporting the gut microbiota, which in turn produces butyrate and other SCFAs essential for digestive health.

Fibre helps blood sugar, and no, you don’t need to cut carbs.

Ede begins by discussing the role of fibre in blood sugar regulation. She said:

“So if you're eating a high carbohydrate diet, fibre can soften your glucose spikes and that's a plus. But there's a more effective way to lower your glucose spikes, it is to not get a glucose spike in the first place and that may not require taking all the carbohydrate out of your diet, it might just mean lowering it to your personal tolerance.”

It’s true that certain types of dietary fibre influence your blood sugar levels after a meal. When ingested, viscous soluble fibre forms a gel-like substance in your stomach that slows digestion, leading to a more gradual absorption of carbohydrates and preventing rapid blood sugar spikes.

And while Georgia’s statement that “a more effective way to lower your glucose spikes is not to get a glucose spike” is technically accurate, it lacks important context and is ultimately misleading.

Many nutrient-rich foods in a balanced diet naturally cause some level of glucose to increase, which is a normal and healthy response to food. The goal shouldn’t be to eliminate all glucose spikes but to manage them effectively. Rather than cutting out foods that cause any rise in blood sugar, the focus should be on reducing frequent and extreme spikes from high-sugar, low-fibre foods.

.avif)

Fibre Supports Digestive Health – Even If It’s Not a “Broom” for Your Colon.

Ede goes on to claim, “Another thing people often say about fibre is that it sweeps your colon clean of toxins that might otherwise build up and cause problems. But there's no evidence that fibre is sweeping anything clean or there's never been a study that demonstrates this.”

This claim oversimplifies and distorts the role of fibre, using a straw man fallacy to dismiss its well-documented benefits. While fibre doesn’t literally “sweep” the colon like a broom, it plays a crucial role in digestive health by adding bulk to stool and promoting regular bowel movements. This helps move waste efficiently through the intestines, reducing the risk of constipation, bloating, and digestive disorders like diverticulitis.

In fact, the scientific evidence is so overwhelming that a recent review published in Nutrients states:

“Of all the beneficial effects of dietary fibre, perhaps the most widely known and appreciated is the effect on gut motility and prevention of constipation. Many studies support such an effect, which appears incontrovertible based on the available evidence.”

Although the body has its own detoxification systems—including the liver and kidneys, which remove toxins—fibre still plays a key role in digestion and elimination. Despite some mixed research, it’s highly likely that a high-fibre diet reduces the risk of colorectal cancer. Research suggests that fibre reduces cancer risk through mechanisms such as:

- Increasing stool bulk and diluting carcinogens in the colon;

- Reducing transit time, meaning harmful substances spend less time in the digestive tract;

- Fermenting into short-chain fatty acids, which support gut health and may have protective effects.

While fibre doesn’t physically “sweep” toxins away, it undeniably supports digestive health and waste elimination.

Fibre couldn’t be more important for your digestion.

Ede continues with: “the biggest myth about fibre is that it's good for digestion because fibre by definition is indigestible by humans.”It's true that dietary fibre is indigestible by human enzymes; however, this indigestibility is precisely what makes fibre beneficial for digestion. Dr Alan Desmond, Consultant Gastroenterologist and gut health specialist said:

In this interview, Georgia Ede dismisses fibre’s role in gut health and motility - an assertion so wildly off the mark that it barely warrants a response.

The overwhelming body of scientific evidence contradicts her claim: fibre plays a crucial role in maintaining gut function, promoting bowel regularity, and reducing the risk of conditions like diverticular disease and colorectal cancer.

She then states that because fibre is “indigestible,” it’s therefore of no use to humans. This reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of how dietary fibre interacts with the gut microbiome. While human enzymes cannot break down fibre, our gut microbes certainly can. These “microbiome-accessible carbohydrates” (MACs) serve as fuel for a healthy gut.

Fiber isn't just about regularity - it's the preferred fuel for our gut microbiome, which influences everything from immune function to mental health. To dismiss fiber is to ignore decades of research showing its role in reducing chronic disease risk and supporting overall vitality.

Georgia acknowledges one of the key reasons fibre is so valuable: its role in the production of butyrate. But then immediately pivots to the false claim that a high-fat ketogenic diet provides the same benefit. Suggesting that a high-fat, fibre-deprived diet could adequately support gut health is not just misleading, it’s a misrepresentation of the science.

Ultimately, this is a mix of outdated concepts, scientific cherry-picking, and false equivalencies that may sound provocative but don’t hold up to basic scrutiny. Fibre isn’t just beneficial - it’s essential.

When assessing health claims, always look for peer-reviewed research and guidance from reputable organisations. Claims that contradict long-standing nutritional evidence should be scrutinised carefully.

A recent episode of the Diary of a CEO podcast featured Georgia Ede, a psychiatrist specialising in nutritional and metabolic psychiatry. During the episode, Ede makes several claims about dietary fibre, suggesting that it’s unnecessary for digestion, does not "clean" the colon, and is not required for other functions that it’s typically associated with. These statements contradict decades of nutrition science and public health advice. So, is fibre essential, or is it an overrated dietary component? We fact-check these claims to provide a much-needed reality check.

Fibre is indigestible by humans, but it plays an essential role in maintaining gut health, promoting regular bowel movements, and supporting beneficial bacteria that produce vital compounds like butyrate. It also helps control blood sugar levels, particularly for individuals consuming carbohydrates. The idea that fibre is unnecessary or harmful contradicts extensive research showing its numerous health benefits.

Misinformation about fibre can lead people to unnecessarily cut it from their diets, which may negatively impact digestion, gut microbiota, and overall health.

Can agroforestry save coffee from climate catastrophe?

Ah, coffee. Few of life’s simple pleasures compare to the revitalizing splendor of this umber nectar. Most would agree. With global coffee production increasing by millions of kilos every year, coffee is the second-most consumed beverage and the second-most traded commodity in the world after water and crude oil.

Now imagine a world where coffee no longer exists. Unthinkable as it may be, that may be our reality by 2050 unless we change the way coffee is produced.

What’s Bad for People is Bad for the Planet

Why the talk of coffee armageddon? Well, there’s a popular saying among the plant-based movement that ‘what’s good for people is good for the planet’ and vice versa. But the inverse of that is also true.

Like the rest of the broken food system, coffee production claims a devastating toll on the environment. And ICYMI: the coffee trade is built on centuries of slave labour. One look at history will tell you all you need to know. Beyond that, modern-day investigations continue to reveal the systemic predatory practices the industry employs to trap millions of domestic workers and smallholder farmers in perpetual cycles of poverty and violence.

Starbucks is a prime example. Early 2024, a consumer advocacy group sued the corporate giant for committing “documented, severe human rights and labor abuses, including the use of child labor and forced labor as well as rampant and egregious sexual harassment and assault” in the countries where it sources its tea and coffee. Later the same year, workers in over 300 of the company’s U.S. stores went on strike to protest unfair labour practices, including low pay and retaliatory firings.

The coffee industry, against all its wishy-washy claims of ethics, is ruthless to the people it employs. But you have to give it props for one thing: its lack of discrimination. Anything is fair game in its destructive path to profit–including the land upon which they cultivate their precious commodity.

The Environmental Toll of Traditional Coffee Farming

The industrial food system is designed to specifically conceal how our food is made and where it comes from. This includes coffee. If you look closely and do a bit of research, it’s all in the language and images they use to market their products.

– David Pritchard, Birds and Beans Co-founder & Co-owner

My biggest issue with coffee is that it’s terrible for the environment. Around the world we collectively drink 2 billion cups a day, yet nobody understands the consequences of that level of consumption.

According to the WWF, entire soccer fields worth of forest have been cut down to grow that coffee, just in the past hour we’re having this conversation. If people knew that, I think they would start thinking about [coffee] differently. If they knew that there were 10-11g of pesticides in every kilogram of beans they bought at the supermarket–some so toxic that they’re illegal in the EU–they’d probably make different choices.

But they don’t know. And it doesn’t help that the industry practices greenwashing.

– Kasper Hülsen, Slow Chief Commercial Officer

Corporate marketing and PR may paint a flattering image of big-name coffee brands, but you don’t grow any company to the gargantuan size of, say, Starbucks, without some sort of cost. Below, we’ll look at four key ways in which that cost is being sorely paid by the planet: through deforestation, biodiversity loss, agrochemical pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions.

Deforestation

Contrary to the more “marketable” image of a sunny little family farm, most coffee available on the market comes from industrial coffee plantations. These are massive monoculture operations that are optimized for one thing and one thing only: maximizing yield in the fastest time to fuel profits. They’re essentially factory farms for coffee.

A key issue here is that similar to animal agriculture, building these coffee plantations requires mass deforestation of land–half of which is illegal where the coffee supply chain is concerned.

Naturally as both consumption and production increase, so does loss of forest. Some may argue that this is a necessary consequence of expanding the market, but the last thing our too-warm atmosphere needs is more CO₂. Worse, cutting down trees also initiates a devastating domino effect on Earth’s biodiversity.

"When you remove the forest, you lose the foundation on which all wildlife thrives,” remarks Kasper Hülsen, Slow’s CCO.

He goes on, “Without birds and wildlife to control insects, farmers turn to pesticides. These chemicals erode the soil, which makes growing healthy crops much harder. So to fix this, they apply synthetic fertilizers. But then these fertilizers end up polluting the groundwater and surrounding land. So you see how [monoculture] creates a vicious cycle, a negative spiral in which everything dies over time.”

Biodiversity Loss

Hülsen isn’t just exaggerating for dramatic effect. Science makes it very clear that loss of wildlife and biodiversity–especially at a grand scale–spells disaster for Earth’s ecosystems. And by extension, for us humans.

Many of the forests in coffee-growing countries are considered biodiversity “hotspots”. They’re home to a rich assortment of tropical plant and animal species, from the tiniest, soil-dwelling microorganisms to important pollinators like bees and migratory songbirds. Though we rarely appreciate their live-giving functions, we rely on every single one of these organisms to provide food, clean air, and water. To kill them off, even inadvertently, is to risk our very survival.

Think of it this way: biodiversity is like a woven net. You cut holes in some areas, and over time, the holes get bigger until the whole net weakens and inevitably falls apart.

And after all the holes that humans have poked in the Coffee Belt’s biodiversity to favour monoculture farming, decades of declining coffee yields and record-high market prices should come as no surprise. How can anyone expect the land to provide when we starve it of its essential elements and nutrients?

Agrochemicals in Traditional Coffee Farming

Speaking of nutrients, let’s talk about synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. Industrial farmers apply these cheap chemicals in droves. And it goes without saying that these compounds make water, soil, animals, and people alike very, very sick.

Coffee is grown in over 70 countries around the world, but the lion’s share comes out of sunny Brazil. Here, pesticide use in coffee production has skyrocketed 190% in a single decade, culminating in the application of roughly 38 million kilograms every year. To make matters worse, the country approved 475 new pesticides in 2019. Over a third of these are so toxic they’re banned in the EU.

In 2022, researchers at the University of Copenhagen showed that exposure to pesticide use is linked to health risks ranging “from skin disorders, respiratory problems, to high blood pressure, organ damage, cancer and cardiovascular disease.” These were studied in coffee farmers with prolonged, direct exposure; but even as consumers at the tail end of the supply chain, we’re not in the clear. Commercial producers use 10-11g of agrochemicals to produce every one kilogram of coffee, and bioaccumulation, which occurs when harmful chemicals build up in living organisms over time, is a real concern.

Synthetic fertilizers follow a similar storyline: sick water, plants, animals, and people. On top of that they also emit nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions

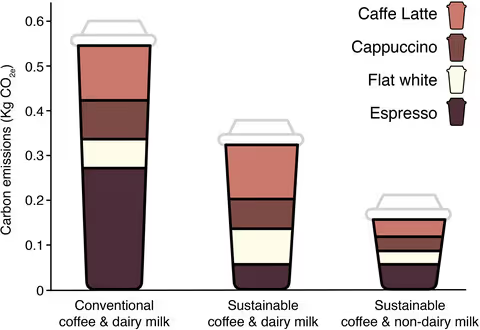

Lastly, we can’t talk about coffee production without mentioning emissions. We’ll stick to just CO2 for the sake of brevity.

Research shows that 15.33 kg is the average carbon footprint for every one kilogram of conventionally produced coffee exported from Brazil and Vietnam to the U.K. Multiply it by the 178 million 60-kilogram bags of coffee produced in a year, it quickly becomes painfully clear just how harmful humanity’s caffeine addiction is on Earth’s climate. Obviously, this number will fluctuate depending on export location, but it’s pretty safe to use it as a baseline since most coffee consumption occurs in the Global North.

(It’s worth noting that 15.33 kg doesn’t account for milk, which also has a massive environmental footprint. So if you prefer your café au lait, I have some bad news for you.)

Where do these emissions come from? In a nutshell: don’t be fooled by the quick-and-easy illusion of convenience culture. The coffee life cycle is long, globe-spanning, and powered by fossil fuels. This TED-Ed video does a great job breaking it down.

Good news is on the horizon, however. The same research reveals that sustainable production methods–such as transporting coffee via cargo ships instead of freight planes and reducing agrochemical inputs–can lower the industry’s emissions by as much as 77%. Which brings us to the star features of this article!

Forest-Grown Coffee is Climate-Smart Coffee

If you’ve been holding your breath as you read; don’t worry, we’re about to turn a positive corner. The transition to more sustainable and regenerative methods of production is well underway in pockets of the coffee world. And with climate change putting pressure on the rest of the industry, it’s only a matter of time until this becomes the new normal.

Without further ado, meet the mould-breaking companies pioneering your new favourite coffee: Slow and Birds and Beans.

How Agroforestry Outshines Monoculture Farming in Coffee Production

Remember those industrial coffee plantations? Danish-based Slow is transforming these degraded lands into lush agroforests where wildlife, smallholder farmers, and coffee crops flourish.

“Monocropping degrades soil health to the point where it becomes very difficult to grow new coffee. That’s why some farmers are selling or abandoning these monoculture farms,” explains Hülsen. “We adopt these farms and essentially rebuild the natural ecosystem from scratch.”

But restoring life on eroded farmland is no simple task. To ensure “this isn’t just some corporate plan that came out of an office in Copenhagen”, to borrow Hülsen’s words, Slow enlisted the help of organizations like the University of Helsinki to develop a meticulous, research-backed ‘forest manual’ to guide their on-the-ground work. (Which they actually do themselves, by the way. 90% of their diverse, 200-person team are based in Vietnam, Indonesia, and Laos where their farms operate.)

Here’s how it works.

Hülsen shares, “At Slow, we plant between 150 to 400 trees per hectare on each of our coffee farms. The number depends on each location, because in some places like Vietnam, the soil can’t support more than 150 trees to begin with. So we plant all these trees, and they help sequester carbon, restore soil health, and provide important canopy cover. Coffea is actually a shade plant, so all of that helps us grow better coffee while lowering our environmental impact.

But we specifically wanted to restore and conserve biodiversity. So again, we start with trees; our team incorporates 20 different types of trees on each of our farms, including endangered tree species. We make sure to cultivate them in a way that creates these four canopy layers–between 2 to 5 meters, 5 to 10 meters, 15 and up to 20 meters–because that’s what’s needed to mimic the natural habitat for birds.

Then to encourage their return, we plant a lot of fruit trees. Fruit trees are insect magnets. And with insects come birds, so they’re a good ‘cheat code’ for bringing back pollinators quickly. As the forest grows, the foundation for natural habitat expands, and you start to see bigger wildlife return too. A year ago, one of our farm’s wildlife cams showed a leopard cat. We saw it both day and night, so we knew it didn’t take a wrong turn during a hunt or anything like that. It lived there, in our forest. That was really gratifying to see.”

As you can see, whereas monoculture disrupts the natural interconnectedness of Earth’s ecosystems, agroforestry nurtures it. Restoring these broken links in biodiversity reaps crucial benefits such as:

- Carbon sequestration

- Lower air and soil temperatures

- Adverse weather protection for crops

- Reduced water runoff and soil evaporation

- Less reliance on agrochemicals (creatures like birds, bats, and spiders are nature’s pest control)

- Improved soil fertility

Let’s make one thing clear, however. Agroforestry may now be garnering more attention as the solution to humanity’s agricultural woes, but it’s far from being a radical new trend or even an invention of modern science. (Though in Slow’s case, it certainly benefited.) This farming method has been practiced by Indigenous communities around the world for centuries.

Even coffee, as a native shade plant, was traditionally grown under the protection of trees before mass industrialization took over. It still is, in some places. You just have to know where to look.

Bird-Friendly Coffee: The Environmental Gold Standard?

Shade-grown coffee certainly isn’t new to Toronto-based David Pritchard and Madeleine Pengelley, who’ve been sourcing and roasting beans from certified bird-friendly farms for more than two decades.

“Back when we first started Birds and Beans, people were mostly just curious about our ‘alternative’ coffee. There wasn’t a deep understanding of the importance of habitat conservation in coffee-making,” shares Pritchard. “We didn’t understand either, initially. It wasn’t until we got into native plant gardening and saw how much wildlife these plants supported that we started to realize: the way we are living is just not conducive to life. Including how we grow our food.”

Indeed, habitat loss has dealt a devastating blow to North American bird populations, which have declined by 30% in just the last few decades. This carries grave consequences, as migratory birds play an important role as pest controllers and pollinators in healthy ecosystems–especially in the tropics, where coffee is cultivated.

Enter ‘bird-friendly’ coffee. This certification tends to–ahem–fly under the radar compared to its “Fairtrade” counterpart. However its ecological significance cannot be overstated. For starters, it was created by Smithsonian scientists in the 90s with the explicit intention to “conserve habitat and protect migratory songbirds.” As such, all coffee producers that want to obtain this certification must:

- Grow coffee in combination with foliage cover and tree diversity, to create suitable habitat for birds and other wildlife.

- Be 100% organic, to ensure no harmful pesticides reach wildlife (or people).

Despite these clear environmental and human health benefits, you’ll scarcely see any brands boast the bird-friendly stamp of approval. Birds and Beans remains the sole provider of this sustainable (and Fairtrade) coffee in Canada more than 30 years after the certification was created. Hopefully with conscious consumerism on the rise, that will soon change.

What’s Good for People is Good for the Planet

At the top of the article, I touched on the link between human suffering and ecological destruction. It’s evident that what hurts one, tends to hurt the other.

But the flip is also true. You probably already see it.

In the context of coffee, the ecological benefits of shade-grown systems like agroforestry are twofold. Not only do they help farmers sustain their work against the unpredictability of climate change (and allow us aficionados to continue enjoying our espressos), they can also help fight climate change itself.

For example, Slow is a carbon-negative business. The power of their coffee farms is such that they absorb more carbon than their entire production value chain releases. And with their SBTi-backed plan to become net zero by 2030, Slow is on the trajectory to fully decarbonize (and humanize) the coffee industry’s destructive business model.

“Our mission from the get-go was to demonstrate that it’s possible to change the broken food system into something better for both people and the environment,” concludes Hülsen. “It’s easy to point fingers at the consumer and say, ‘This is only their responsibility, they need to change their behavior.’ Consumers do have a responsibility; their spending power influences the market. But the coffee industry also needs to wake up, take a hard look in the mirror, and acknowledge their responsibility by saying, ‘We need to stop producing coffee that harms the planet.’

So that’s why we are here. It’s absolutely possible to be part of the solution rather than part of the problem, and we show people every day.”

The science is clear. Climate change is pushing Earth and all who live on her–coffee, birds, and humans alike–onto a precarious edge. It’s essential that as consumers we put our spending power where it counts. So forget Starbucks. By opting to support coffee companies like Slow and Birds and Beans, who are actively investing in agroforestry-grown, sustainable coffee, we can prevent the impending plummet over that edge.

And perhaps in the process, we can save what really matters.

The spark of awe that coloured David Pritchard’s voice captures it all:

“The migrations. They’re absolutely amazing, you know. These tiny birds–some of them weigh almost nothing–fly thousands of miles every year to return to the same place. They know where home is, because they practice site fidelity at both ends of their trip. It’s kind of miraculous when you think about it. Preserving that beauty is absolutely worthwhile. And it’s as easy as changing the coffee you drink.”

No, honey isn’t unhealthy because it spikes your blood sugar, but why does this influencer say the opposite?

Addressing Nutrition Misinformation on Social Media

To fully understand the impact of misleading social media posts on nutrition topics, what we need to ask ourselves is: what questions do these posts get us to focus on? And perhaps more importantly, what do they leave out? For a detailed analysis of the long-term impact of similar posts on our overall reasoning about nutrition and on our relationship with food, you can read our other fact-check of a claim comparing smoothies with 19 doughnuts here. Indeed the example presented in this article is not isolated; it is part of a broader trend on social media. Repeated exposure to similar content is what can end up affecting the way we approach food and nutrition.

_______

We have contacted Jessie Inchauspé and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

The information provided here is for general information purposes only, and should not be considered medical advice. If you have Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes or any condition requiring careful blood sugar monitoring, please consult your healthcare provider for personalised guidance tailored to your specific needs.

This perspective highlights the need to ask the right questions when we navigate online nutrition information. When we focus on biological processes like blood sugar spikes, without the wider context in which they affect human health, we end up with sensationalised statements like Dr Gundry’s, who once claimed that if you feed your child grapes, you might as well give them a chocolate Hershey’s bar instead, because they both contain sugar. Comments like these do little to improve our understanding of nutrition; they create scaremongering and can contribute to negative and harmful relationships with food.

Blueberries might contain more antioxidants, but it’s not the only measure that matters.

It’s true that the antioxidant content of blueberries is generally much higher than that of honey, as reported in the Antioxidant Food Database. However, even this can vary a lot, depending on the variety of blueberry and the variety of honey. While Jessie is likely making a general comparison to show that the amount of antioxidants in honey can be found elsewhere for less sugar, her subsequent claims about health impacts are misleading. Sugar and antioxidants are just two factors of a complex food matrix that exists within honey, and your overall dietary pattern.

Yes, sugar spikes your blood glucose, but this doesn’t mean honey is bad for you.

“Honey contains glucose and fructose - these both have impacts on your health.” Jessie writes in her caption.

A diet rich in simple sugars can increase calorie intake beyond needs and is associated with negative health outcomes such as poor cardiovascular health. As with most of Jessie’s posts, she claims that because a food is high in sugar, it spikes blood sugar and is, therefore, not healthy. However, will a teaspoon of honey, poured over a bowl of porridge, spread on your toast, or paired with Greek yoghurt, cause these ill-healths? No, and this is where Jessie’s claim is flawed.

Pure honey may have health benefits that cannot be understood by examining the blood sugar spike alone. For example, honey contains trace amounts of bioactive compounds with potential antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects, depending on the source. Jessie also cites no research to show that honey is associated with poor health outcomes and doesn’t acknowledge the studies that show it may have health benefits.

Honey may confer some small but beneficial effects on your health. A meta-analysis of 18 controlled trials with 1105 participants suggests that honey might improve glycemic control and lipid levels. However it’s important to note that the certainty of the evidence is low, and the effects on fasting glucose and total cholesterol varied by floral source and honey processing. Meta-analyses like these are more reliable data sources than measurements of glucose spikes from an individual, whose health background is completely unknown.

Honey probably has varying impacts on your blood glucose levels.

The graph in Jessie’s post is based on one person’s blood sugar response to honey, most likely recorded using a continuous glucose monitor (CGM). It shows that a teaspoon of honey causes a spike in blood sugar, which then falls back within the normal range. It is important to note that no citations are given for this illustrated graph and in reality there is variation between the type of honey consumed with some varieties considered to be low GI in comparison to glucose.

Even so, this graph may have little meaning for your own health. Research shows that blood sugar spikes, measured with CGMs, can vary greatly in the same person in response to consuming the same meal at different times. So, the one data point Jessie shares has limited meaning for your own health. Another paper showed that CGMs are highly unlikely to be able to tell you what foods are “right” or “wrong” for you based on the glucose response to that food.

Additionally, there is limited evidence for the negative impact of glucose spikes that fall back within the normal range on long-term health.

An important distinction here is for people with pre-diabetes or diabetes, where blood sugar control is important and should be monitored with the support of a healthcare team.

We need context, Jessie!

Context, context, context.

Jessie compares a teaspoon of honey to half a blueberry, focusing on the sugar and antioxidant content, and the impact on blood sugar spikes. However, honey is rarely consumed by itself, and is often added to meals. Therefore, the impact on blood glucose spikes (which may have little impact for individuals without diabetes anyway) is likely different to what she shares in her post. There are several ways in which context needs to be reintroduced here:

- Focusing on realistic eating patterns

Posts like this entirely remove single ingredients or foods from the context of how they’re actually consumed, and more generally of a person’s diet.

Jessie does point out, “So to me, honey is in the category of eating it for pleasure if you love it, but its health benefits don’t outweigh all of the sugar that it contains and the impact of that sugar on your health.”

Half a blueberry is also an unlikely serving size for anyone. Blueberries are consumed as a snack or in larger quantities (e.g., a handful), where their antioxidant benefits are cumulative, and they contain more sugar – which, we can’t stress enough, is not inherently bad for you!

This post is yet another example of a false equivalence, where two foods are presented together in a way that makes them seem equivalent, when in fact they cannot be compared in a meaningful way. Comparing the nutritional impact of a teaspoon of honey to half a blueberry doesn't align with real-world usage patterns and creates an unrealistic framing of their roles in a diet. This type of information might make compelling social media content, but it does little to empower the consumer to gain a better understanding of nutrition.

- A teaspoon of honey is not just a teaspoon of sugar

“Sugar is sugar”, Jessie writes in her post, which is frequently said by those claiming all sugar is unhealthy, no matter the dietary source. And while too much sugar, in the context of an unhealthy diet, can negatively impact health, the argument can be misleading without added context.

For example, one review reports that different sources of dietary sugars can impact glycaemic control, blood pressure, inflammation, and acute appetite differently. Specifically, they found that compared with sugar-sweetened beverages, honey reduced fasting glucose levels.

Dr Idz commented on this exact issue, in an interview given to BBC Radio London, in which he explains that what we need to focus on is what the sugar is added to. What else does it come with?

Sugar is the same molecule, but the question is what ‘package’ is the sugar involved with? [...] Whilst it's important to educate people about the long-term effects of excessive sugar consumption, sugar’s not ‘the devil’; the problem is excessive sugar, not sugar that exists naturally within foods.

As a medical expert, I see firsthand the confusion caused by oversimplified comparisons like ‘grapes versus candy bars.’ While it’s true that sugar content matters, nutrition is about more than just isolated macronutrients. Grapes, for instance, provide antioxidants, fiber, and hydration—benefits absent in processed candy.

Alarmist statements can distort public understanding, emphasizing fear over facts and contributing to unhealthy relationships with food.When engaging with nutrition information online, I recommend a three-step approach: verify the credibility of the source, evaluate the broader nutritional profile of foods, and consult professionals for nuanced advice. Misleading claims, when amplified, undermine trust in science and make it harder for individuals to make informed choices about their health.

Beware of oversimplified claims online, especially those that focus exclusively on your glucose response to a food to determine its impact on health. These claims often miss the wider context of how that food can contribute to a healthy diet.

On 22nd January, Jessie Inchauspé, aka the ‘Glucose Goddess’ published an Instagram reel comparing half a blueberry to a teaspoon of honey, and the way they affect your health. She said “Honey is sugar, it contains a lot, a lot of sugar, it will spike your glucose levels,” followed by “Health benefits don’t outweigh all of the sugar that it contains and the impact of that sugar on your health." We bring a much-needed reality check to these claims, because frankly, who eats half a blueberry or a teaspoon of honey alone?

Comparisons between honey and blueberries are overly simplistic. They present a false equivalence and have little meaning for your health.

This claim is an example of fear-mongering at its best. Posts like this often strip away context to fit with a narrative, positioning the influencer’s programme or product as the ultimate solution.

Reimagining the food system through circular thinking

The world is at a critical juncture: the way we produce, consume, and discard food is unsustainable. Currently, a staggering one-third of all food produced globally is wasted, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity loss, and resource depletion. Amid this crisis, the concept of the circular economy is emerging as a transformative solution to reimagine how we manage food systems.

Unlike the traditional linear approach of "take, make, dispose," a circular economy focuses on minimizing waste, maximizing the use of resources, and regenerating ecosystems. When applied to the food system, it envisions a closed loop where food is produced sustainably, consumed efficiently, and any waste is reused or returned to nature without harm.

Here’s how forward-thinking innovators are embracing this model to shape the future of food.

Innovations Driving the Circular Food System

1. Notpla: Seaweed-Based Food Packaging

Plastic pollution is a global environmental crisis, and food packaging plays a significant role in the problem. Enter Notpla, a company founded by Pierre-Yves Paslier and Rodrigo García González, that uses seaweed and plant-based materials to create alternatives to single-use plastics.

Notpla's products include biodegradable sachets for condiments and water, as well as compostable food containers. These innovations not only reduce reliance on fossil fuel-derived plastics but also decompose naturally without leaving microplastic residue. In a circular food economy, solutions like Notpla ensure that packaging is not an environmental burden, aligning production with the regenerative principles of nature.

2. Trashy: Turning Food Waste into Resources

In a world where millions go hungry, the fact that up to 40% of food in the United States is wasted is both a moral and environmental challenge. Trashy, founded by Kaitlin Mogentale, tackles this issue by transforming food waste into high-value goods.

By collecting food scraps from restaurants, farmers, and grocery stores, Trashy creates nutrient-rich compost and products like organic fertilizers. This practice not only diverts waste from landfills but also enhances soil health, enabling farmers to grow food sustainably. Trashy exemplifies how the circular economy can transform waste into opportunity, closing the loop between food production and consumption.

3. SweGreen: Vertical Farming for Urban Areas

As urbanization accelerates and arable land becomes scarce, innovative farming techniques are essential. SweGreen, led by Sepehr Mousavi, integrates circular principles into urban agriculture through vertical and hydroponic farming systems. These farms use significantly less water, eliminate the need for soil, and rely on renewable energy sources.

SweGreen grows fresh produce directly in urban areas, reducing transportation emissions and ensuring fresher food for consumers. Any organic waste generated is either composted or repurposed as feedstock for further production, showcasing how cities can support local, sustainable food ecosystems.

4. Toast Ale: Brewing Beer with Surplus Bread

Bread is one of the most wasted food items globally. Toast Ale, co-founded by Louisa Ziane and Tristram Stuart, transforms surplus bread into craft beer, creating a delightful product while addressing food waste.

The brewing process substitutes bread for some of the malted barley typically used, reducing the resources needed for production. Toast Ale partners with bakeries, grocery stores, and food distributors to rescue bread that would otherwise be discarded. By highlighting food’s potential even at the "end" of its lifecycle, Toast Ale is a shining example of the circular economy in action.

Why the Circular Economy Is Essential for Food

The food system is a major contributor to climate change, responsible for roughly one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions. A circular food economy can address these environmental pressures by:

- Reducing Waste: Reclaiming surplus food and repurposing organic materials can drastically cut emissions from landfills.

- Improving Efficiency: Optimizing resource use across the supply chain minimizes environmental impact.

- Regenerating Ecosystems: Practices like composting return nutrients to the soil, supporting biodiversity and enhancing resilience.

Challenges and Opportunities Ahead

While the circular economy offers a compelling vision for the future of food, challenges remain. Scaling solutions like those developed by Notpla and SweGreen requires significant investment, policy support, and consumer buy-in. Also, transitioning to a circular system involves rethinking entrenched practices in agriculture, packaging, and waste management.

Despite these hurdles, the potential benefits are transformative. A circular economy could create new jobs, reduce environmental harm, and build a food system that can sustain future generations.

How Consumers Can Drive Change

Consumers play a crucial role in advancing the circular food economy. Here are a few ways to contribute:

- Support Circular Businesses: Choose products from companies like Toast Ale and Notpla that prioritize sustainability.

- Reduce Food Waste: Plan meals, store food properly, and compost scraps when possible.

- Advocate for Change: Push for policies that support waste reduction and sustainable agriculture.

A Future Worth Building

The circular economy offers a pathway to a more sustainable and resilient food system. By rethinking waste, embracing innovative solutions, and prioritizing regeneration over exploitation, we can ensure that food serves not just as sustenance but as a cornerstone of a thriving planet.

Organizations like Notpla, Trashy, SweGreen, and Toast Ale are already proving that this vision is achievable. Their work is a reminder that while the challenges we face are immense, so too are the opportunities to create lasting, positive change. The future of food—and the planet—depends on how quickly we embrace these transformative ideas.

Farmers say lab-grown meat 'not the enemy'. Here's why

According to new research from the Royal Agricultural University (RAU), British farmers are open to collaborating with “lab-grown” meat producers in the coming years. Here’s why.

UK farmers curious about the potential of lab-grown meat

Lab-grown meat - also known as cultured, cultivated, or synthetic meat - is a form of cellular agriculture where real muscle tissue is produced by growing animal cells in a laboratory. As the climate crisis threatens humanity’s increasingly unstable food system, some people believe that protein alternatives such as lab-grown meat could be part of the solution.

The topic remains contentious, and Italy has banned the development of lab-grown meat products, saying that they represent a “social and economic risk.” The US state of Florida banned production in May 2024, and Romania and Hungary have also proposed bans.

However, according to RAU researchers, British farmers are more receptive to the new technology than some of their global counterparts. Over 80 farmers spoke to RAU for the new study and mostly said that they did not view alternative proteins as a major threat.

The study’s lead author, RAU professor Tom MacMillan, told the BBC that while there was “concern” over how the technology could impact farmers, there was also a “lot of curiosity” about whether lab-grown meat and traditional farming could unite for the common good.

“Farmers were really engaged in the practical possibilities, supplying ingredients to the technology, maybe even hosting production units on their farms,” he added.

Farming by-products could make cultured proteins more sustainable

One of the main obstacles to cultivated meat is cost, both to produce and to purchase. Streamlining production will enable large-scale manufacturing and more consumer-friendly prices. One way to achieve this could be by using by-products from farming.

Rapeseed oil leftovers are rich in amino acids, which are some of the most expensive and least sustainable ingredients required for cultivated meat production. According to the new RAU report, using these by-products in place of synthetic amino acids could significantly streamline the manufacturing process, reducing energy, water, and land use.

The report also found that linking cultured meat production with farming could benefit farmers themselves, mediating some of the issues they face in the current system and addressing concerns over the potential threat alternative proteins represent.

“Building bridges with farmers is certainly in the cultured meat companies’ interests, as some are starting to see,” said MacMillan. “More surprisingly, we found that keeping the door open may serve farmers better too.”

In addition to cultured animal-derived products, plant-based meat also represents a potential route to link modern alternative proteins with the traditional farming sector. Many UK farmers are already supplying plant-based brands with the vegetables and grains they require, which provides agricultural workers with a steady revenue stream and producers with a regular source of locally-produced ingredients for alternative proteins.

Breaking down the ‘beef’

In November 2024, researchers from the University of Bristol (UoB) also carried out a study on British animal farmers’ attitudes towards plant-based diets and vegans, in particular. The research found that farmers’ attitudes are complex, including both positives and negatives.

While some criticized vegans for failing to take into account the problematic nature of other forms of farming, globalization, and growing import culture, others praised the culture for prompting conversations about animal welfare and the need to reduce meat consumption.

The two groups are often depicted by the media as polarised, but research indicates many shared goals and other connections between the UK’s farming communities and vegans. As with other hot topics in the so-called “culture wars,” many apparent divisions are exaggerated or possibly fabricated entirely, with misinformation obstructing constructive dialogue.

Meanwhile, new organizations like Vegans Support the Farmers (VSF) have launched in solidarity with the agricultural community and to advocate for fair prices and local, sustainable food production. VSF is also actively fundraising to support the mental health of farmers, where mental health problems are common and suicide rates are notably high.

“We realized that farmers and vegans have many more things in common than divide us – a need for a sustainable future for the next generation,” VSF co-founder Kerri Waters told Plant Based News in 2023. “As vegans, we oppose injustice against all living beings, including farmers, because it is the right thing to do … It is time the movement matured to a level where we can have honest and humble conversations with farmers.”

Crossing the divide

A 2023 report by UK-based think tank Green Alliance titled Crossing the Divide also highlighted the need for so-called “incompatible” worldviews and demographics - such as vegans and animal farmers - to find further alignment and “break the deadlock.”

The report breaks differing opinions on the land down into four distinct “worldviews,” including Traditionalists, who see food producers as “guardians of the countryside;” Technovegans, who promote technology as an efficient and effective alternative to traditional farming; Agroecologists, who believe in a system-wide transition to sustainable and accessible food production; and Sustainable Intensifiers, who assume an unavoidable increase in demand for animal products and promote technological farming innovation.

In particular, Green Alliance suggests an alliance between Technovegans and Agroecologists as the best path forward for European countries, as it could lead to “positive environmental outcomes” while retaining strong support for established rural livelihoods.

As noted in the research by UoB and RAU, many people are already open to and seeking this kind of collaboration, which will be essential in fortifying the food system and fighting the climate crisis without alienating the UK’s rural population of over 10 million people.

Separate groups representing a unified, pro-sustainability front could then encourage more effective interventions by the state and corporate bodies. As noted by the Green Alliance, “Policy makers, confused over the best course of action for agriculture, intervene haphazardly, or not at all. As a result, progress is slow or non-existent, and the climate and biodiversity impacts of the current food system remain unaddressed.”

Food reform that centers growers

The RAU report, UoB study, and Green Alliance’s report all highlight the rapidly evolving landscape of agriculture. The Green Alliance depicts how the current food system is unsustainable, but that connection and collaboration will be required if it is to be salvaged.

Meanwhile, both the RAU and UoB studies indicate that British farmers could be receptive to transformative changes in the food system, provided there is still a place for them within it. Overall, fostering further dialogue between these groups and countering divisive misinformation could help pave the way for a sustainable and equitable food system.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, a growing body of research - including the two-part independent review The National Food Strategy - indicates that farmers will need to be at the very heart of any meaningful food system transformation.

Urgent and far-reaching change is essential, but agricultural workers themselves are indispensable. The food system will continue to require farmers, and as a result, they should be at the forefront of all new developments. The government should also empower farmers to make positive environmental efforts, via legislation and subsidy reform.

FDA bans the use of Red No.3 in food because of links to cancer. What’s the actual risk?

The evidence linking food dye to ADHD is weak

While the FDA ban on Red Dye No. 3 is solely linked to the study on cancer, claims have also been made about potential links between red dye and increased symptoms of behavioural conditions, such as ADHD, in children.

For example, the EWG claims “memory problems in children” and a Fox News article states “It has also been linked to behavioral issues in children, including ADHD,” but neither provides any further context or nuance about these findings.

Danielle Shine, registered dietician and PhD candidate researching nutrition misinformation on social media, says that “unfortunately, there’s a lot of misinformation about artificial food dyes causing hyperactivity or ADHD in children.” She adds that “currently, there’s no strong scientific evidence to support these claims. While some studies suggest a potential link between synthetic food dyes and hyperactivity in a small subset of more susceptible children, findings have been inconsistent, and the overall evidence remains inconclusive. Overall, while a small group of children may be more sensitive to synthetic dyes, the broader evidence does not support a causal link between food dyes and ADHD or hyperactivity.”

Over the last few decades, several studies have examined the associations between food dye consumption and increased symptoms of behavioural conditions, such as ADHD, in children.

In 2012, results from a meta-analysis suggested a small association between food colour additives and exacerbated ADHD symptoms. However, the result “was not reliable in studies confined to Food and Drug Administration-approved food colors.” Additionally, the authors noted that the results were derived from small sample sizes, and not generalisable to a wider population.

A later meta-analysis, released in 2021 by the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA), combined all relevant studies and conducted its own research to examine the association between food dyes and adverse neurobehavioral outcomes. They found an association between food dye consumption and adverse neurobehavioral outcomes in children, including ADHD.

However, the studies included in these meta-analyses, which are the basis for many of the claims made online, have major limitations. Many of the studies were conducted 30-40 years ago, with very small sample sizes, and cannot isolate one dye such as Red Dye No. 3 from other dyes and preservatives. However, on the basis of these and other meta-analyses, researchers are calling for more work to be done in this area.

Despite the suggested associations, there is still no evidence showing that food dyes such as Red Dye No. 3 are directly causing exacerbated symptoms of behavioural conditions such as ADHD.

Broader Implications

While advice to avoid synthetic dyes might seem harmless or prudent, the FDA’s recent ban on Red No. 3 has broader implications that extend beyond the dye's use.

Because of the quantities humans would have to consume for adverse health outcomes, the ban is unlikely to protect human health. However, it could negatively impact the perception and dissemination of evidence-based health information online.

Balanced nutrition and health advice doesn’t always suit social media algorithms, which tend to amplify the loudest voices. Unsubstantiated claims about the dangers of consuming products containing synthetic dyes have been circulating on social media for years. Health influencers like Mark Hyman are applauding the recent ban, which could give more validity to other widely shared and alarming claims about varying food products. The timing of the ban is being credited to Robert F. Kennedy Jr. 's influence, which could also fuel support in some other inaccurate health claims he’s made, which include topics such as vaccine safety, Covid, or fluoride in drinking water.

While most people would agree that the food industry needs to be reformed in order to prioritise people’s health, the sharing of alarming, unsubstantiated claims about synthetic dyes does not achieve this goal.

Repeated exposure to alarming claims, regardless of their scientific validity, can distort public understanding of actual health risks. What is at stake here is risk perceptions, which are influenced by how often a threat gets repeated through media exposure.

This dynamic not only erodes trust in the scientific process but also empowers health influencers who thrive on misinformation, drowning out the voice of experts and shifting focus from real dietary concerns to sensationalised ones.

As a result, people might overly fixate on avoiding ingredients which do not pose a proven risk, losing sight of the big picture of addressing broader dietary patterns. In other words, the popularity of toxic food thinking on social media platforms gets people to focus on the wrong issues. In reaction to the FDA’s announcement of its recent ban, Dr. Andrea Love states that “anti-science rhetoric based on chemophobia is a distraction from REAL food-related issues that impact health,” among which we find “food deserts, low fiber consumption by 90% of Americans, lack of affordable healthcare, overall dietary composition, reducing cost of fresh and frozen produce, encouraging conventional and modern farming methods-that ARE safe and nutritious, overall lifestyle & exercise habits.”

In extreme cases, this misinformation can escalate, as seen with individuals forgoing proven medical treatments illustrating the potential for real harm when misplaced health narratives dominate the conversation.

We have contacted Dr Mark Hyman and are awaiting a response.

There is no evidence that red food dye causes cancer in humans

The FDA ban is based on evidence linking Red Dye No. 3 to cancer in male lab rats. However, online claims are now linking Red Dye No. 3 to cancer in animals and humans, which goes beyond the available evidence.

For example, the Environment Working Group (EWG), one of the groups lobbying for the ban, described Red Dye No. 3 as a “Chemical linked to cancer, memory problems in children,” while the Center for Science in the Public Interest (SCPI) said, “Red 3 has been banned from use in topical drugs and cosmetics since 1990, when the FDA itself determined that the dye causes cancer when eaten by animals.” These articles, and other online claims, fail to mention any evidence or context for human health. By not mentioning the dose or the fact that the link is based on one study, claims appear exaggerated.

The study, conducted in the 1980s, found that male rats who consumed high levels of Red Dye No. 3 developed thyroid tumours. Two key points mean we can’t use the data to know that it causes cancer in humans: the dose and the fact that humans are not rats.

As Dr Andrea Love explains in her post addressing this issue, cancer occurred when rats ate 4% of their body weight in Red Dye No.3. “That is equal to a person weighing 150 lbs eating 102 grams of red 3 every day for months,” said Dr Andrea Love. “The average person MIGHT eat 0.2 milligrams per day. That’s 7,500 TIMES LESS than what those rats were fed.”

The FDA “noted that studies had not found a link to cancer in other types of animals.” They also stated that the claims that humans are at risk because red dye is used in foods “are not supported by the available scientific information.” Jim Jones, the FDA’s deputy commissioner for human foods, also said in a statement, “Importantly, the way that FD&C Red No. 3 causes cancer in male rats does not occur in humans."

Context

Why did the FDA decide to ban the use of Red No. 3 dye in food and drugs?

The ban is in response to a 2022 petition from several groups, including the Centre for Science in the Public Interest, calling for the enforcement of the Delaney Clause.

The Delaney Clause is a law that prohibits the use of any chemical that causes cancer in humans or animals in food, at any dose. This is important because a ban under this clause does not necessarily mean that there is definite evidence of harm in humans.

The Delaney Clause was enacted in 1958, but some researchers contest its utility in today’s context, calling it a ‘regulatory relic’ in its current form. According to cancer research scientist John H. Weisburger, the Delaney Clause was entirely justified in the context of the 1950s, as we knew a lot less about what causes cancer in humans and the mechanisms of carcinogenesis. In his paper, published over thirty years ago, he argued for an update of the Delaney Clause in light of the then-current scientific knowledge; for example, advances in analytical chemistry have allowed scientists to accurately determine trace amounts of chemicals, which wasn’t possible in the 1950s.

Although the Delaney Clause, introduced in 1958, was intended to protect public health, it no longer reflects modern scientific understanding. Banning additives like Red No. 3 under this law misrepresents current science, fuels unnecessary fear, and diverts attention and resources away from more pressing public health issues, such as ensuring food equity. While consumer safety is crucial, relying on an outdated law that treats animal and human risks as equal is fundamentally flawed. It also undermines scientific consensus and contributes to the erosion of public trust in evidence-based nutrition guidance.

For children with hyperactivity or ADHD, reducing foods containing artificial dyes may be worth exploring. However, it’s important to understand that hyperactivity stems from multiple factors, including genetics and environmental influences. Artificial food dyes are likely just one small piece of the puzzle and eliminating them may not always lead to noticeable changes in behavior. The most important focus should be on improving overall diet quality.

Parents are encouraged to follow evidence-based guidelines for a balanced, nutrient-dense diet that includes a variety of whole foods from all major food groups. This approach naturally reduces the intake of artificial dyes and also limits other ingredients like added sugars, saturated fats, and excess salt, all of which support overall health and wellbeing.

There’s no strong evidence that Red No. 3 increases cancer risk in humans. The decision to remove it from foods and drugs in the U.S. was primarily based on studies involving male rats that developed thyroid tumors after being exposed to extremely high doses of Red No. 3. These tumors were linked to a rat-specific hormonal mechanism that doesn’t occur in humans.

Look at the quality of the evidence available and whether studies were done on humans or only on certain animals. If they were only on animals, it’s unlikely we can say anything certain about the health impacts on humans.

On Wednesday, January 15th, the FDA banned the use of a synthetic red dye, Red Dye No. 3, typically added to food and drinks in the US. Prior to and following the ban, many claims online about the health risks of this synthetic dye, linking it to cancer and ADHD in children, have been made. Dr. Mark Hyman is among those who claim that Red No.3 and other synthetic dyes “wreak havoc on our bodies.” However, the evidence for the impacts on human health is not strong. Here, we break down what you need to know.

There is no scientific consensus suggesting that Red Dye No. 3 causes cancer in humans, and the FDA acknowledges that the mechanisms causing cancer in rats do not apply to humans. The ban enforces a law that some experts argue is outdated. However, discussions around the ban on social media have amplified its significance, in a way that lacks scientific nuance or context.

The ban on Red Dye No. 3 raises questions about the application of outdated regulations in light of modern scientific evidence. It also highlights the potential for public misunderstanding of health risks, as alarmist narratives on social media can amplify unsupported claims, shifting attention away from pressing dietary and public health concerns.

Latest fact-checks, guides & opinion pieces

.svg)