Are plastic greenhouses in Spain caused by plant-based diets?

Fact-Check Part 3: Is a Plant-Based Diet to Blame?

The post’s framing suggests plant-based diets are environmentally harmful because of plastic pollution from greenhouses. However, a comprehensive review by Poore and Nemecek (2018) in Science found that plant-based diets still have a far smaller environmental footprint—including lower greenhouse gas emissions, water use, and land use—compared to diets high in meat and dairy.

A 2023 meta-analysis in Nature Food reinforced these findings, showing that vegan diets contribute 75% less greenhouse gas emissions than diets high in animal products. The net ecological benefit of plant-based diets remains positive, even when accounting for intensive crop systems.

Conclusion & Score

Final Verdict: 🟠 Misleading

While the image is real and plastic agriculture in Almería is a serious environmental concern, attributing this problem primarily to plant-based diets is oversimplified and misleading. The greenhouse agriculture sector supports global food demand across all diets, not just veganism.

Fact-Check Part 2: Who Is Driving the Demand?

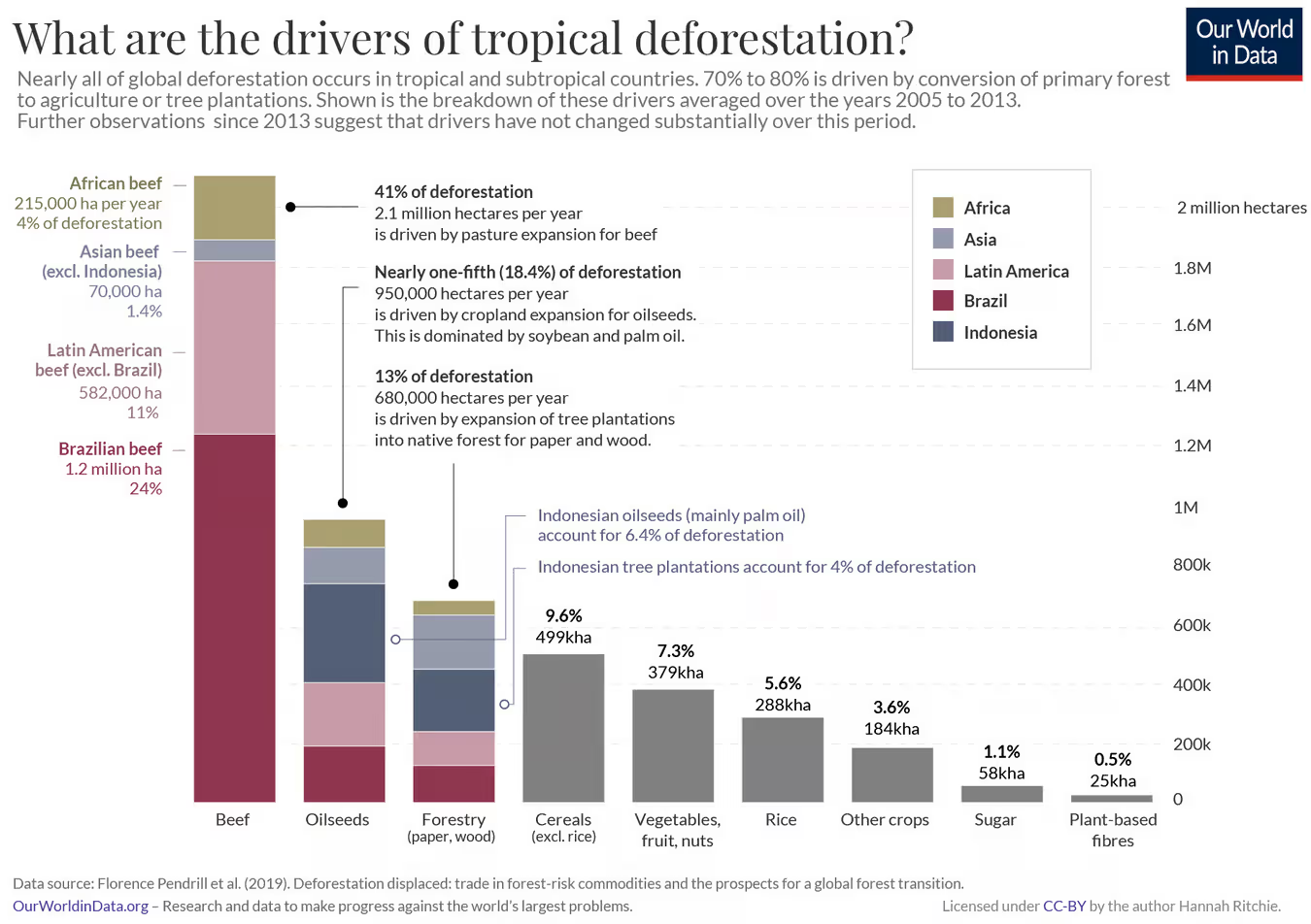

The crops grown in Almería—tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, courgettes—are staples in omnivorous, vegetarian, and vegan diets alike. While demand for plant-based products has increased, these vegetables have always been widely consumed, regardless of dietary preference. Research shows that the largest driver of land conversion and deforestation globally is livestock, or more specifically, growing food for farmed animals to eat.

According to research from Ritchie & Roser (Our World in Data, 2020), only a small proportion of greenhouse-grown produce can be tied specifically to vegan diets. The largest share is linked to general food consumption patterns, especially in high-income countries seeking out-of-season fresh produce.

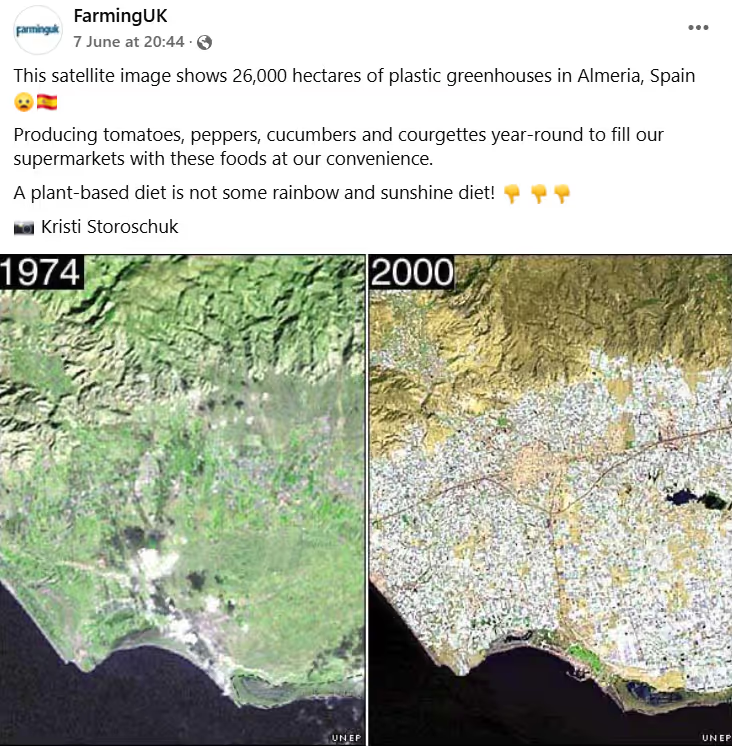

Fact-Check Part 1: Is the Image Accurate?

Yes, the satellite imagery is authentic. The NASA Earth Observatory has published similar comparative visuals documenting the transformation of the Campo de Dalías in Almería into one of Europe’s largest greenhouse hubs. By 2022, over 40,000 hectares were covered in plastic greenhouses.

Satellite images confirm the rapid expansion of intensive horticulture in southern Spain, especially since the 1960s. The vegetables grown here are exported across Europe, contributing to the year-round availability of fresh produce in supermarkets.

🥔 Dig Deeper: Images can be powerful, but they don’t always tell the full story—especially when used without context.

Posted by FarmingUK on Facebook (7 June), an image shows two satellite images (from 1974 and 2000) illustrating rapid expansion of plastic-covered greenhouses in Almería, Spain. It suggests that this expansion is directly linked to the growing demand for plant-based diets and implies negative environmental impacts of such diets.

Claim:

“This satellite image shows 26,000 hectares of plastic greenhouses in Almería, Spain... Producing tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers and courgettes year-round… A plant-based diet is not some rainbow and sunshine diet!”

Greenhouse agriculture in Almería serves a global market that includes both plant-based and omnivorous eaters. While the region raises valid concerns about plastic waste, labor conditions, and water usage, attributing it primarily to veganism distorts the broader agricultural reality.

With rising awareness around sustainability, these kinds of claims can unfairly undermine plant-based diets using out-of-context visuals. This can create confusion and backlash, especially when backed by agricultural lobbies with vested interests.

Can slaughter ever be humane? A closer look at the industry standard

What Does “Humane Slaughter” Actually Mean?

The term “humane slaughter” refers to practices intended to minimize animal suffering during the killing process. In many countries, including those in the E.U., the U.S., and the U.K., slaughter laws require that most animals be rendered unconscious before being killed—a process known as stunning.

This includes:

- Captive bolt stunning for cows

- Electrical stunning for pigs and poultry

- Gas stunning using carbon dioxide (commonly used for pigs and poultry)

But while these methods are considered best practices, there is no global consensus on what constitutes “humane.” And more importantly, these practices are often imperfectly implemented—especially at the scale required to meet global meat demand.

Does Stunning Always Prevent Suffering?

Unfortunately, no. Stunning is not always effective, particularly in high-speed slaughterhouses where time pressures reduce the chance of proper technique.

- Research has shown that electrical stunning of pigs fails up to 31% of the time, and bolt stunning for cows worked on the first attempt only 28% of the time.

- The U.S. Government Accountability Office has documented significant violations of the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act in American meat facilities, particularly under high production pressures.

- In undercover investigations, animals are sometimes improperly stunned and regain consciousness before or during slaughter—a clear failure of the process.

Even when done correctly, stunning does not erase the stress, fear, and suffering animals often experience during transport, handling, and pre-slaughter confinement.

How Does Industrial Slaughter Impact Animal Welfare?

Slaughterhouses that process thousands of animals per day operate on tight schedules. Speed and efficiency are prioritized, leaving little room for individualized care. This creates conditions where:

- Workers are rushed, increasing the chance of error

- Animals may be improperly restrained, leading to injury

- Stress levels are high, due to noise, unfamiliar environments, and handling

Multiple undercover investigations from The Animal Justice Project documented how industrial meat plants regularly fail to uphold even minimal welfare standards. In some facilities, animals are routinely subjected to painful procedures and handled roughly by undertrained or overburdened workers.

The industrial context directly undermines the possibility of truly humane treatment.

Is the Idea of “Humane Slaughter” an Oxymoron?

Many animal welfare scientists and ethicists argue that the phrase “humane slaughter” is fundamentally contradictory. Taking a life—especially of an animal not in pain or distress—is inherently a moral dilemma.

While pain can be reduced, death is never painless in the existential sense. The animal loses everything. And even in best-case scenarios, the fear and stress leading up to slaughter are difficult, if not impossible, to eliminate.

This tension has led critics to question whether “humane slaughter” is primarily a marketing term—designed to ease consumer guilt rather than reform the system.

Why Do People Believe Humane Slaughter Is the Ethical Option?

Because the industry—and many certification bodies—promote the idea. Labels like “Certified Humane,” “RSPCA Assured,” and “Animal Welfare Approved” offer consumers reassurance, even though their standards vary widely and are not always well-enforced.

Consumers understandably want to reduce harm. Choosing “humanely raised” products feels like a middle ground between concern for animals and dietary habits. But that middle ground may be more symbolic than substantial, especially when the reality of slaughter doesn’t match the rhetoric.

What Does 'Harm Reduction' or Welfarism Mean?

Not everyone agrees on whether humans should eat animals, but for now, many still do. That’s the reality: more than 70 billion land animals are killed every year for food. If we include fish, the number reaches into the trillions.

This raises an important question: If we can’t stop all animal slaughter overnight, what can be done to reduce suffering in the meantime? This is where harm reduction and welfarism come in.

Harm Reduction

Harm reduction means trying to make things less bad. It doesn’t solve the root problem, in this case, the killing of animals, but it aims to reduce the pain and suffering involved. Think of it like a first step, not a final goal.

Some examples:

- Eating fewer animal products can reduce overall demand and thus the number of animals killed.

- Looking for welfare labels might encourage better conditions (though labels can be misleading).

- Demanding transparency in slaughterhouses helps hold companies accountable.

What Is Welfarism?

Welfarism is the idea that while animals are still being used and killed by humans, we should at least try to treat them better. This could mean:

- Better living conditions before slaughter.

- Faster, more “humane” killing methods.

- Laws to reduce extreme cruelty.

Welfarism is often seen as a compromise, a middle ground between doing nothing and going fully vegan. But it’s controversial. Some argue it creates a false sense of progress and makes consumers feel more comfortable with animal use, instead of challenging it.

What About Abolitionism?

On the other hand, abolitionism is the belief that using and killing animals is fundamentally wrong—no matter how “nicely” it’s done. This is the core of the modern vegan movement: a push not just for less harm, but to end animal exploitation altogether.However, abolitionism isn’t always easy for the general public to embrace. That’s why welfarist measures often gain more support—they feel more practical or less extreme to people who aren’t ready for major lifestyle changes.

Is There a Better Way Forward?

The question of humane slaughter leads naturally into a larger conversation about our food system, and whether truly compassionate alternatives exist.

Animal-free foods, cultivated meats, and plant-based options are evolving rapidly. While not without challenges, these emerging technologies offer a pathway toward reducing the need for animal slaughter altogether.

Just as the concept of “humane slaughter” aims to reduce harm, a transition toward alternatives can eliminate it.

Reimagining Ethics in Our Food System

“Humane slaughter” may be seen as less harmful by some sections of society, rather than overt cruelty, but it is not a solution. It’s a compromise within a system that prioritizes speed, scale, and profit over sentience. By questioning these terms, and looking more closely at what they obscure—we can move toward a food system based on transparency, empathy, and evolution.

Red 3 in the spotlight: should you stop eating cocktail cherries?

We have contacted Sunna Van Kampen and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Claim 1: Red Dye 3, a “banned food ingredient that’s been linked to cancer.”

Fact-Check: It is true that as of January 15, 2025, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) banned Red 3 (Erythrosine, FD&C Red No. 3) for use in food and ingested drugs (source). The way the claim is phrased, however, is misleading in the sense that it does not accurately represent the reasons behind this ban and exaggerates the risks associated with the occasional consumption of foods containing Red 3, such as cocktail cherries.

The FDA ban is based on the Delaney Clause of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which prohibits the use of any chemical that causes cancer in humans or animals in food, at any dose. This is important because a ban under this clause does not necessarily mean that there is definite evidence of harm in humans.

The FDA's decision was prompted by a public petition. Concerns mainly stem from a study conducted in the 1980s, showing that high doses of Red 3 caused thyroid tumors in male rats, but this effect is due to a rat-specific hormonal mechanism not present in humans.

While the ban was a response to public concern, it is important to remember that there is no evidence Red 3 causes cancer in humans at typical exposure levels; the animal studies involved doses far higher than those encountered in the human diet.

For a deeper dive into the reasons behind this recent ban, the Delaney Clause, or health concerns related to Red 3, you can read this other related fact-check.

Claim 2: “[Red 3]’s been banned by the FDA for use in food, but weirdly, in Europe and the UK, it’s only allowed in cocktail cherries.”

Fact-Check: The implication behind this claim seems to be that European and UK legislation do not go as far as the FDA, which recently implemented a full ban of Red 3 for use in food. Yet the UK and the EU still allow its use in cocktail cherries. A few things need to be untangled here.

The FDA ban has not been enforced yet, with deadlines in 2027 and 2028 for food and drugs, respectively. So you may still be able to find Red 3 in American supermarkets until then. Up until this ban occurred, EU (and UK) legislation was actually a lot stricter. Indeed, Erythrosine (Red 3, E127) has been heavily restricted in the European Union since 1994. Its use is primarily limited to cocktail cherries, candied cherries, and a few other niche products (such as some decorative items and certain pharmaceuticals).

The EU sets a maximum level of erythrosine allowed in these products: up to 200 mg/kg in cocktail/candied cherries (source).

More importantly, comparisons between American and European legislations regarding food safety might make compelling social media content, but they are of little relevance to the consumer. This is because depending on what ingredient you are looking at, you might find stricter European legislation, or stricter American legislation. Crucially, just because one country enforces stricter legislations does not mean that the consumption of an ingredient is a serious health hazard and must be avoided in all situations. The reason behind discrepancies is grounded in different approaches and regulatory philosophy:

Risk-Based Approach vs. Precautionary Principle

- US: Historically, the US has used a more risk-based approach, allowing substances unless clear and significant risk is demonstrated at typical exposure levels.

- EU: The European Union often applies the precautionary principle, meaning substances are heavily restricted or banned if there is any credible evidence of risk, even if that risk is not conclusively proven in humans. This has led to erythrosine being restricted since 1994 to only a few uses.

EU regulations set acceptable daily intake (ADI) levels and restrict uses based on cumulative risk assessment.

Permitted Quantities

While Tonic Health’s video could come across as implying that EU and UK regulations are not as strict as in the US, it is important to remember that permitted quantities are strictly enforced, and are set to keep consumer exposure well below the established Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI), which is 0.1 mg per kg of body weight per day.

The EU’s precautionary approach means that erythrosine is only allowed where alternatives may not provide the desired intense, stable red color (as in cherries) and where overall population exposure is expected to remain very low (source; source).

The maximum levels allowed are as follows:

- Cocktail and candied cherries: Up to 200 mg/kg.

- Bigarreaux cherries in syrup and cocktails: Up to 150 mg/kg.

The following paragraph, extracted from the European Food Safety Authority’s review of the use of Erythrosine as a food additive, is very useful to get a glimpse of how these permitted quantities are assessed, and how ADIs are determined:

“The Panel considered Erythrosine has a minimal effect in humans at a clinical oral dose of 200 mg daily over 14 days, while a dose of 60 mg daily was without effect (Gardner et al., 1987). The current ADI adopted by the JECFA and the SCF is based on this study. The Panel concurred with their identification of this as the critical study. The 60 mg dose was taken to be the equivalent of 1 mg/kg bw/day. By applying a safety factor of 10 to allow for the small number of subjects used in the study and its relatively short duration, an ADI of 0-0.1 mg/kg bw per day was derived. The Panel concludes that the present database does not provide a basis to revise the ADI of 0.1 mg/kg bw/day.”

When no consideration is given to the dose in which these ingredients are present in our food, or the context in which they are consumed - cocktail cherries, for example, don’t tend to be eaten in excess - we end up with absolutes along the lines of ‘never eat those cherries.’ This can be problematic in the long-term as people get more and more exposed to this type of narrative on social media platforms, potentially fostering toxic relationships with food.

Final Take Away

Erythrosine is allowed in cocktail cherries in Europe and the UK, with strict limits (200 mg/kg) to ensure exposure remains very low. Consuming cocktail cherries occasionally, even at these maximum levels, is not considered to meaningfully increase cancer risk for humans according to current scientific evidence and regulatory reviews.

At the end of the day, cocktail cherries offer little to no significant nutritional value. However, this type of messaging fits into a broader pattern in which discussions about food are decontextualised, often generating fear. The phrase “linked to cancer” is particularly alarming, and when used without context - especially on social media - it can undermine nutritional literacy and understanding. The following post by Dr. Andrea Love is a great reminder of the impact of this type of messaging:

Always consider both the dose and context of food additives: they are both often overlooked within social media narratives.

On May 18th, Sunna Van Kampen (Tonic Health) shared on social media that there is a food ingredient (Red 3) banned in the US because of cancer links, but still found in all UK supermarkets, specifically in cocktail cherries, suggesting that we should stop eating those products. In this fact-check, we look at the reasons behind these differing regulations to place the claim in context.

Full Claim: “Banned food ingredient that’s been linked to cancer that is still in every supermarket in the UK. It’s been banned by the FDA for use in food, but weirdly, in Europe and the UK, it’s only allowed in cocktail cherries. Probably because [...] someone did a good job at lobbying the government saying they have to be in these cherries to get that colour that everybody knows and loves. So it’s time for change, gotta stop eating those cherries ‘cause it’s been linked to cancer and that ingredient is banned. You won’t see Red 3 on the back, by the way, it’s called its colour, Erythrosine.”

While Red 3 has been banned by the FDA for use in food in the US (pending enforcement), it is only permitted in the UK and EU in very limited products like cocktail cherries, and at strictly regulated levels. Cocktail cherries don’t really provide nutritional value, but there is no evidence that their occasional consumption poses a meaningful cancer risk to humans. Therefore the suggestion that they must be avoided is unsupported by scientific evidence.

Comparisons between countries’ food safety regulations can easily spark fear and confusion. Understanding the real risks (and the reasons behind different rules) helps you make informed choices.

Umami under attack: the weird history of MSG racist panic (and why it was wrong)

MSG Mania: Unpacking the Racist Myth Behind a Flavorful Scapegoat

Monosodium glutamate – better known as MSG – is one of the most beloved and maligned ingredients in modern cooking. It’s a simple seasoning salt that delivers the savory umami flavor found in tomatoes, cheese, and seaweed. Yet for decades, many Western diners have feared MSG as a hidden menace in takeout, blaming it for everything from headaches to heart palpitations. “No MSG” signs became a common sight at Chinese restaurants trying to appease wary customers. How did a commonplace flavor enhancer turn into a culinary villain? The answer involves bad science, media hype, and a hefty dose of xenophobia. This article explores how the myth of MSG’s “dangers” arose – and why it’s finally crumbling under the weight of facts.

A Brief History of Umami: MSG’s Origins and Early Use

MSG wasn’t invented in a lab to plague late-night takeout lovers – it was discovered in a kitchen. In 1908, Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda isolated a compound from kombu seaweed broth that made food taste especially savory. He named this distinct taste umami (meaning “pleasant savory taste”) and patented the crystalline seasoning derived from it as monosodium glutamate. Ikeda’s invention was quickly commercialized in Japan under the brand Ajinomoto, meaning “essence of taste”.

The use of MSG soon spread around the globe. By the 1920s, Chinese cooks were making their own version from wheat and marketing it as “Ve-Tsin,” which similarly translates to “flavor essence”. Throughout the mid-20th century, MSG quietly became a staple ingredient not just in Asian kitchens but in Western processed foods. American manufacturers added MSG to everything from canned soups to TV dinners to boost flavor, and even the U.S. Army mixed it into soldiers’ rations for tastier meals. For many years, people on both sides of the Pacific enjoyed this “secret sauce” of savory cuisine without much fanfare or fear.

The Birth of ‘Chinese Restaurant Syndrome’

The backlash against MSG can be traced to a single spark: a brief letter published in 1968 in the New England Journal of Medicine. In it, a doctor described experiencing strange symptoms – numbness, weakness, rapid heartbeat – after eating at a Chinese restaurant. He speculated that anything from the soy sauce to the cooking wine or perhaps MSG might be to blame. That speculation was all it took. The letter – ostensibly a tongue-in-cheek musing that editors later revealed was essentially a hoax – unleashed decades of misunderstanding and stigma. Soon, this supposed collection of symptoms had a name: “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.”

Medical journals and newspapers alike latched onto the concept. The NEJM printed a slew of responses from other doctors claiming they or their patients felt sick after eating Chinese food, listing ailments from dizziness to flushing – though tellingly, their accounts were wildly inconsistent. No two people reported exactly the same symptoms, and some even admitted the power of suggestion or anxiety could be at work. The journal’s editors themselves hinted the syndrome might be fictitious, but the media didn’t convey the skepticism. Catchy headlines about “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” spread the idea that something in Asian cuisine – implicitly, MSG – was making people ill. A myth was born, and it stuck. By 1993 the term even landed in the dictionary (Merriam-Webster), defined as a condition allegedly caused by MSG-laden Chinese food.

Bad Science Feeds the Panic

In the wake of the frenzy, scientists attempted to investigate MSG – but some early studies only fanned the fears. Researchers in the late 1960s fed laboratory mice sky-high doses of MSG, even injecting it directly into their brains in amounts equivalent to a human eating multiple ounces of pure MSG at once. Not surprisingly, the mice showed ill effects, and alarming reports emerged that MSG could cause brain lesions, stunted growth, or nerve damage. These sensational findings grabbed headlines, and consumer advocates reacted swiftly.

By 1969, prominent activists like Ralph Nader were pushing to ban MSG in baby food, and major baby food manufacturers voluntarily pulled MSG from their products amid public outcry. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which had long classified MSG as “Generally Recognized As Safe,” launched a review under pressure. “No MSG” labels began appearing on restaurant windows and food packaging as a marketing badge of purity. The idea that MSG was a hidden harmful “chemical” had officially entered the public consciousness.

The trouble was, much of the anti-MSG science was deeply flawed. In one oft-cited experiment, subjects were given MSG on an empty stomach in large quantities – an approach almost guaranteed to cause transient discomfort in anyone, much like wolfing down too much salt or vinegar alone. Other trials failed to use proper blinding, so participants knew when they were ingesting MSG and might have imagined symptoms due to expectation or anxiety. Over the next few decades, as more rigorous research was conducted, the consensus in the scientific community coalesced: at normal dietary levels, MSG isn’t the bogeyman it was made out to be.

What Science and Regulators Say About MSG

So, is MSG actually safe to eat? According to toxicologists and health authorities around the world, the answer is yes. Monosodium glutamate has become one of the most exhaustively studied food additives in history. Hundreds of scientific studies – including controlled human trials – have failed to find evidence that MSG causes any widespread or consistent adverse effects. While a small subset of people might have a mild sensitivity and experience short-term symptoms if they consume a huge amount on an empty stomach, researchers have found no toxic or long-term health impact from normal MSG use. In fact, our bodies metabolize the glutamate from MSG in exactly the same way as the glutamate present naturally in foods like tomatoes or Parmesan cheese.

Regulators have taken note. The U.S. FDA maintains MSG on its list of approved food ingredients and states that MSG is safe when consumed at customary levels. International experts agree: the Joint expert committee of the World Health Organization has never found a reason to set an upper limit on MSG’s use, and the European Food Safety Authority affirms its safety within typical dietary intakes. In short, MSG is harmless – except, of course, for making your food taste delicious. “There is not one scientific paper to prove that it’s bad for you,” notes celebrated chef Heston Blumenthal, who calls the MSG scare “complete and utter nonsense”. The enduring belief that MSG is uniquely dangerous simply isn’t supported by science or medicine.

Fear, Flavor, and Fictions Fueled by Racism

If the science doesn’t support MSG as a dietary villain, why did so many people come to loathe and fear it? The answer lies not in biology, but in bias. The very name “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” points to the misconception’s insidious core: it singled out Chinese cuisine (and by extension, Chinese people) as suspect. This framing tapped into old Western prejudices portraying Asian food as unhygienic, exotic, or untrustworthy. As Korean-American chef David Chang observes, avoidance of MSG became “a cultural construct” – essentially a socially accepted excuse to distrust foreign cooking under the guise of health concerns. In plainer terms, it was ignorance and xenophobia masquerading as wellness.

Consider that Americans happily ate MSG for years in things like Campbell’s soup and KFC chicken without raising an eyebrow. Only when MSG was associated with Chinese restaurant cooking did it suddenly become a supposed health hazard. No one warned about an “Italian Pizzeria Syndrome” from the glutamate-rich parmesan on your pasta, or a “Mom’s Home Cooking Syndrome” from the umami in a pot roast. Yet Chinese restaurants were unfairly cast as vectors of a fake syndrome. “You know what causes Chinese Restaurant Syndrome? Racism,” the late Anthony Bourdain once quipped, cutting to the chase. His point: diners were quick to blame a “mysterious Oriential additive” for their post-meal discomfort rather than, say, overeating or simply the bias planted in their heads.

The targeting of MSG also dovetailed with a broader history of anti-Asian sentiment. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Chinese immigrant communities in the U.S. endured racist laws and slanders (from the Chinese Exclusion Act to lurid rumors about Chinese restaurant sanitation). The MSG myth arrived in that cultural context, making it easier for people to believe and propagate. Chinese-American restaurateurs bore the brunt of this stigma: they had to alter recipes, hang “No MSG” signs, and watch customers scrutinize their cuisine with undue suspicion. Meanwhile, predominantly white-owned food companies continued using MSG in snacks and frozen dinners with little fanfare or outrage, a telling double standard.

The myth wasn’t just bad science – it was racial scapegoating, and it caused real economic and reputational harm.

The Comeback: MSG’s Reputation Gets a Reboot

Today, MSG is undergoing a rehabilitation of sorts, as chefs and consumers alike wake up from the long-running moral panic. In recent years, prominent culinary figures and scientists have pushed back against the anti-MSG narrative. Chef David Chang has been vocal in defending the seasoning, noting that MSG is simply sodium and glutamate – “something your body produces naturally and needs to function” – and that multiple studies have failed to show it makes anyone sick. “It only makes food taste delicious,” he points out. Other food world luminaries, from cookbook author Fuchsia Dunlop to molecular gastronomy guru Heston Blumenthal, have called for MSG’s stigma to end, pointing out that demonizing this additive is both unscientific and unfair. Some trendy restaurants now openly sprinkle MSG like a gourmet ingredient, celebrating its umami-boosting powers.

Even the institutional record is being corrected. In 2020, Ajinomoto (the original MSG manufacturer) launched a public campaign to “reclaim MSG’s honor.” The company enlisted Asian-American celebrities in a cheeky video declaring that “MSG is delicious” and petitioned Merriam-Webster to change its entry for “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome”. The dictionary editors agreed to revisit the term, ultimately updating it to note that it’s dated and offensive – essentially an antiquated myth, not a real medical condition. Public opinion is slowly following suit: a 2022 survey found that younger consumers are far less likely to believe MSG is harmful compared to previous generations, and food products that proudly tout MSG or “umami” are gaining popularity.

It’s a remarkable turnaround for a seasoning once cast as a public enemy. While a kernel of the old fear still pops up now and then (often echoing outdated information), the broader trend is moving toward acceptance. Many people have come to realize what the science showed all along: that MSG is, at its core, just a useful flavor enhancer with an unjust bad rap. The real lesson is less about chemistry and more about cultural humility. As one food writer famously asked, “If MSG is so bad for you, why doesn’t everyone in China have a headache?” The obvious answer is that they don’t – and neither do the rest of us. It turns out, the only thing we truly had to fear about MSG was fear itself (and maybe missing out on some really tasty food).

Are non-organic strawberries unsafe? Examining the evidence

We have contacted Dr. Watts and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

While organic strawberries are less likely to contain synthetic pesticide residues and may be preferred by those seeking to minimise exposure, they are not always residue-free and are generally more expensive. This is an important consideration for many families. Besides, there is currently no evidence that eating organic foods is associated with better health outcomes (source).

Final take away

The framing of the messaging conflates the detection of any residue with exceeding safety thresholds and risks unnecessarily alarming the public. Fear-inducing messages around the consumption of popular fruits among children can do more harm than good. For example, one mum’s comment on the post expressed significant concern over having fed her daughter strawberries the day before seeing this video, emphasising “the guilt you think you are feeding them well.” This type of comment clearly shows the impact of this type of public messaging, which overlooks the many benefits of fruit consumption.

Claim 1: A government study “showed 95% of all of the strawberries that were sampled in the UK had a level of pesticide toxicity that had [...] exceeded the threshold of safety.”

Fact-Check: The government study referred to did find that 95% of the samples analysed (111 out of 120) had pesticide residues, but these were at or below the Maximum Residue Level (MRL) set by law. However, 0% of samples contained residue that exceeded the MRL.

MRLs are set by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE). The following extract from the report mentioned by Dr Watts is useful to place those findings in context, without which consumers might make decisions based on fear rather than understanding:

“MRLs are set in law at the highest level of pesticide that the relevant regulatory body would expect to find in that crop when it has been treated in line with Good Agricultural Practice. When MRLs are set, effects of the residue on human health are also considered. The MRLs are set at a level where consumption of food containing that residue should not cause any ill health to consumers.” (source)

The report also clearly emphasises that MRLs should not be understood as health safety limits. They are designed to assess that the pesticides are being used correctly, and even if foods are over this limit, this does not mean that they are unsafe to eat. If a food has been found to contain residues above the MRL, a risk assessment is conducted to determine if there may be health concerns. If that is the case, the FSA will determine if further action is required (for example, if the foods in question need to be recalled). In most cases, there isn’t (source).

The implication that the report’s results mean that non-organic strawberries in the UK are not safe to eat is misleading.

Claim 2: Non-organic strawberries contain unsafe levels of PFAS, which are “linked to cancers, immune disorders, reproductive disorders, neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s.”

Fact-Check: This type of claim is prevalent on social media, and can seem particularly alarming. It follows this structure: “Avoid this food; it contains [name of chemical/substance], which is linked to [list of serious health conditions]”. While some link might exist, without context those claims tend to exaggerate risks for consumers, and can lead to unnecessary fear.

Let’s start by defining PFAS before placing the claim in context.

What are PFAS?

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are synthetic chemicals that have been used for decades in industrial and consumer products for their resistance to water, oil, heat, and stains (e.g., in non-stick cookware, water-repellent fabrics, firefighting foams, and some food packaging). Due to their chemical stability, they do not break down easily in the environment or human body, hence the nickname "forever chemicals." PFAS have also been found in certain pesticide formulations, either as active ingredients or as unintentional by-products of manufacturing. Importantly, this is not common to all pesticides, and regulatory bodies are currently investigating the extent of their presence and potential dietary relevance (source).

PFAS have been linked to a range of health concerns, including certain cancers, immune system effects, and metabolic disorders (source). However, much of the evidence comes from populations with higher-than-average exposures (such as contaminated water supplies), and research is ongoing to clarify the risks at the lower exposure levels typical for the general population (source).

The British government report did not find that non-organic strawberries contained unsafe levels of PFAS. It found that most of the samples tested contained residues, and it is true that non-organic strawberries are among the foods containing the highest level of pesticides. This does not mean that strawberries are ‘unsafe’, however; rather the main concern with PFAS is their overwhelming presence, and continued exposure over time, particularly for those with jobs that regularly expose them to pesticides.

The evidence tells us that the nutritional benefits of consuming fruits and vegetables, including strawberries, far outweigh the potential risks from low-level exposures (source), and this is the type of nuance that is often lost within social media narratives.

Is buying organic a ‘must’?

Lastly, Dr Watts says that if you consume strawberries, and particularly if your children do, you “must” buy organic. Is organic always better? Registered Nutritionist Rhiannon Lambert explains:

While it is true pesticides can build up if consumed in excess over time, the benefits of consuming the food outweighs this and most pesticides can be removed by simply washing your fruit and vegetables. (Lambert, 2024: 144)

No food is perfect. If you go looking for something to criticise, you’ll always find it. But fear-driven messages like this only serve to distract from what decades of evidence makes clear: eating more fruit and vegetables, whether organic or not, is one of the best things we can do for our health.

Be cautious of absolute terms like "must" or "always" in health-related claims. Such language often oversimplifies complex issues and may not account for individual circumstances or the broader context.

In a video posted on April 24th, Dr. Sam Watts claimed that a UK government study found 95% of strawberries sampled had pesticide levels exceeding safety thresholds, making them “arguably the most toxic food in your home.” We bring you a reality check, considering both the issues linked to pesticide residues on fresh food products, and the benefits of consuming strawberries.

The UK government's 2022 pesticide residue monitoring program found that 95% of strawberry samples contained residues; however 0% exceeded the legally established Maximum Residue Levels (MRLs). While concerns about the generally overwhelming presence of PFAS, otherwise known as ‘forever chemicals,’ are legitimate, concluding from this report that non-organic strawberries are unsafe to eat is misleading.

Understanding the nuances of official reports on pesticide residues is important for making informed dietary choices. Misinterpretations can lead to unnecessary fear, potentially discouraging the consumption of nutritious fruits like strawberries. This fact-check aims to clarify potential misconceptions, promoting balanced and evidence-based decisions.

“Net zero beef?” Why sustainability claims need more than headlines

On May 6th, Agricarbon, a company specialising in soil carbon measurement, published a case study titled “Net Zero Beef Is Now a Reality.” As a linguist, I was immediately struck by the contrast between the certainty that resonates behind this headline, and the more provisional tone of the introduction: “Regeneratively farmed beef cattle could sequester more carbon than they emit, according to modelling results from a McDonald's-sponsored project at FAI Farms.”

Whether this represents a true breakthrough or is still a work in progress, the premise is undeniably intriguing. For the general public, who have long been told that reducing beef consumption is essential for a sustainable food system, the promise of net zero beef might suggest that no dietary changes are needed after all. However, after consulting several experts to examine the facts behind these claims, it quickly becomes clear that the situation is far more complex.

Regardless of the accuracy of these claims, the search for ways to make beef production more sustainable is both positive and necessary. The real issue arises when we leap to the conclusion that such innovations mean dietary changes are no longer required. We need to embrace an AND rather than an OR approach: reduce beef consumption AND make its production more sustainable.

Let’s explore this further, drawing on insights from experts. Matthew Shribman, CEO and Chief Scientist at AimHi Earth, suggests to reframe the issue to better understand its implications:

“Imagine a rich valley overflowing with thriving nature: forests, wetlands, natural meadows. There’s a lot of carbon stored here. And, as well as all of that carbon, this thriving nature is producing fresh air, clean water and more.

Now let’s imagine we have to clear some of this wild nature to grow food to eat.

To keep it simple, let’s focus on our protein supply.

Do we focus on

(a) raising cows, or

(b) growing beans?

If we choose cows, we will have to clear 20x more land to get the same amount of protein (source).

Of course, when we clear this wild nature and turn it into farmland, we’re going to lose some of those “ecosystem services”, like fresh air and clean water. And we’re going to lose a lot of stored carbon too.

Intuitively, it therefore makes sense that beans are almost always going to be more sustainable than beef, since they take up so much less space. And that intuition is spot on.

This new method for farming beef claims to be “carbon-negative” – it claims to store carbon. But there’s an important question to ask here: “carbon-negative relative to what?”.

The answer is that it’s carbon negative relative to cleared farmland.

In other words, it stores carbon compared to a depleted bit of land used for industrial farming.

This isn’t a bad thing - it’s a good thing. Every little helps, and so this piece of research isn’t pointless.

What if we had to choose?

But crucially, if we had to choose between:

- keep 95% of the land wild, and grow beans;

- clear all the land and farm beef with this new method;

- clear all of the land and farm beef on it intensively

…then the first option is by far the most valuable among them.

An even better option would be to integrate cows into the bean farm, as part of a healthy ecosystem, where there are just a few cows, acting as a service to the land… rather than as a product for McDonald’s…”

Environmental science is inherently complex, because it has to consider numerous interrelated factors to fully grasp the impact of various practices and policies. Matthew Shribman offers valuable perspective by placing innovations aimed at reducing the carbon footprint of beef production within the broader context of food systems and sustainability. To further unpack the specific findings of this study, we also spoke with environmental scientist Nicholas Carter, who examined its details more closely:

“FAI [Food Animal Initiative] Farms’ “net zero beef” claim, funded by McDonald’s, is based on selective modeling from just 3 of 105 fields, with major flaws like shifting sample sites, missing bulk density data, and uncounted carbon from imported hay.

The initiative builds on earlier Adaptive Multi-Paddock (AMP) grazing studies in the U.S. backed by McDonald’s, Shell, Exxon, and Cargill, tying regenerative ranching to Big Oil’s climate PR. Tools like GWP* are used to downplay methane’s emissions from cattle, basically allowing a baseline of emissions that aren't counted. Meanwhile, the farm’s biodiversity and soil carbon levels remain far below those of rewilded ecosystems. This is corporate-funded messaging designed to protect beef supply chains and fossil fuel interests, not deliver real climate solutions.”

Innovation in livestock systems is valuable, but it must be evaluated alongside broader land use priorities, biodiversity goals, and genuine climate impact—not just carbon accounting.

Rather than viewing regenerative beef as a replacement for dietary shifts, it should be seen as one piece of a much larger puzzle. If we are serious about addressing the climate and ecological crises, we must resist the temptation of convenient narratives and remain committed to both reducing meat consumption and improving how meat is produced.

Latest fact-checks, guides & opinion pieces

.svg)