Umami under attack: the weird history of MSG racist panic (and why it was wrong)

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

MSG Mania: Unpacking the Racist Myth Behind a Flavorful Scapegoat

Monosodium glutamate – better known as MSG – is one of the most beloved and maligned ingredients in modern cooking. It’s a simple seasoning salt that delivers the savory umami flavor found in tomatoes, cheese, and seaweed. Yet for decades, many Western diners have feared MSG as a hidden menace in takeout, blaming it for everything from headaches to heart palpitations. “No MSG” signs became a common sight at Chinese restaurants trying to appease wary customers. How did a commonplace flavor enhancer turn into a culinary villain? The answer involves bad science, media hype, and a hefty dose of xenophobia. This article explores how the myth of MSG’s “dangers” arose – and why it’s finally crumbling under the weight of facts.

A Brief History of Umami: MSG’s Origins and Early Use

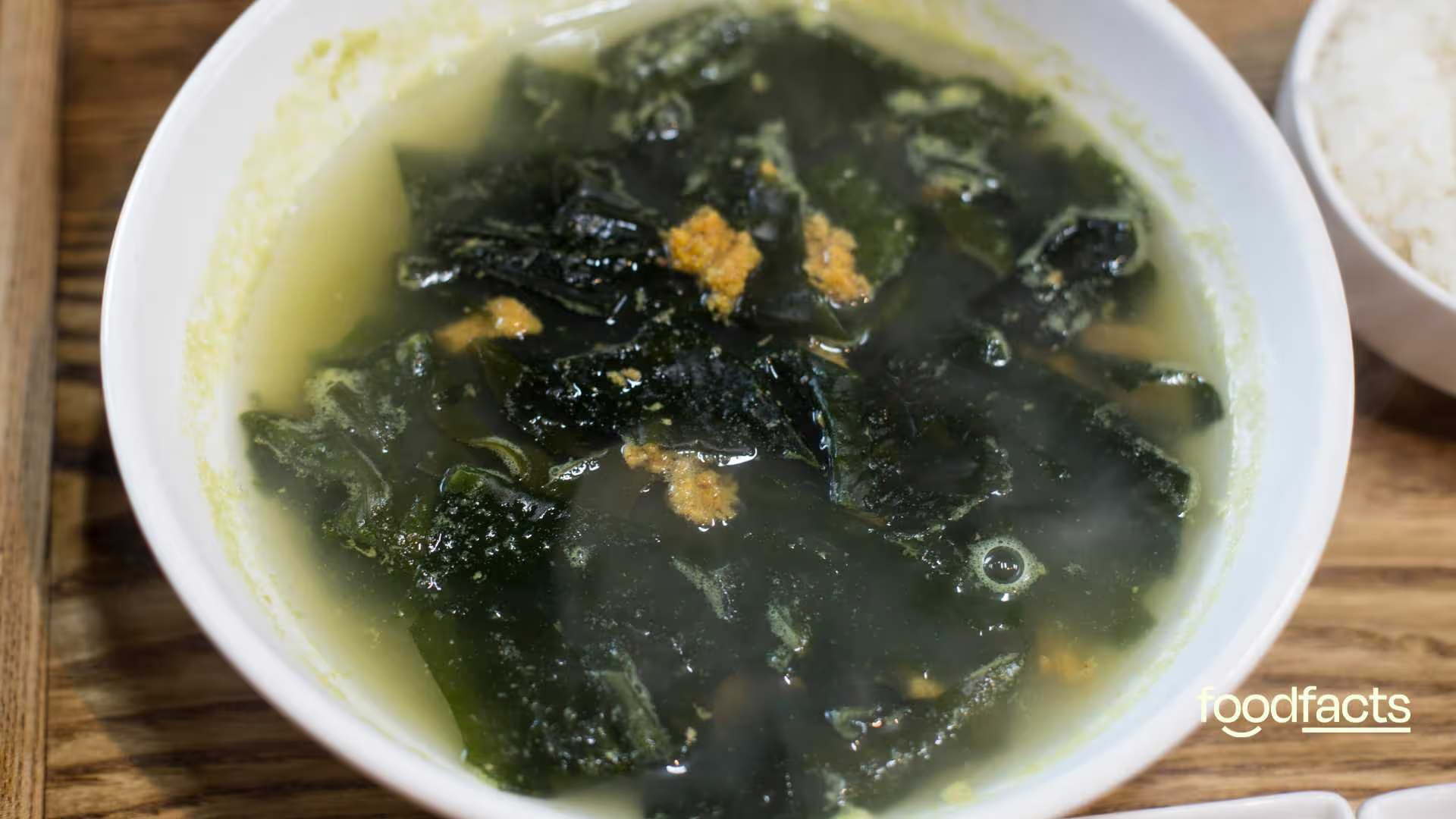

MSG wasn’t invented in a lab to plague late-night takeout lovers – it was discovered in a kitchen. In 1908, Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda isolated a compound from kombu seaweed broth that made food taste especially savory. He named this distinct taste umami (meaning “pleasant savory taste”) and patented the crystalline seasoning derived from it as monosodium glutamate. Ikeda’s invention was quickly commercialized in Japan under the brand Ajinomoto, meaning “essence of taste”.

The use of MSG soon spread around the globe. By the 1920s, Chinese cooks were making their own version from wheat and marketing it as “Ve-Tsin,” which similarly translates to “flavor essence”. Throughout the mid-20th century, MSG quietly became a staple ingredient not just in Asian kitchens but in Western processed foods. American manufacturers added MSG to everything from canned soups to TV dinners to boost flavor, and even the U.S. Army mixed it into soldiers’ rations for tastier meals. For many years, people on both sides of the Pacific enjoyed this “secret sauce” of savory cuisine without much fanfare or fear.

The Birth of ‘Chinese Restaurant Syndrome’

The backlash against MSG can be traced to a single spark: a brief letter published in 1968 in the New England Journal of Medicine. In it, a doctor described experiencing strange symptoms – numbness, weakness, rapid heartbeat – after eating at a Chinese restaurant. He speculated that anything from the soy sauce to the cooking wine or perhaps MSG might be to blame. That speculation was all it took. The letter – ostensibly a tongue-in-cheek musing that editors later revealed was essentially a hoax – unleashed decades of misunderstanding and stigma. Soon, this supposed collection of symptoms had a name: “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.”

Medical journals and newspapers alike latched onto the concept. The NEJM printed a slew of responses from other doctors claiming they or their patients felt sick after eating Chinese food, listing ailments from dizziness to flushing – though tellingly, their accounts were wildly inconsistent. No two people reported exactly the same symptoms, and some even admitted the power of suggestion or anxiety could be at work. The journal’s editors themselves hinted the syndrome might be fictitious, but the media didn’t convey the skepticism. Catchy headlines about “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” spread the idea that something in Asian cuisine – implicitly, MSG – was making people ill. A myth was born, and it stuck. By 1993 the term even landed in the dictionary (Merriam-Webster), defined as a condition allegedly caused by MSG-laden Chinese food.

Bad Science Feeds the Panic

In the wake of the frenzy, scientists attempted to investigate MSG – but some early studies only fanned the fears. Researchers in the late 1960s fed laboratory mice sky-high doses of MSG, even injecting it directly into their brains in amounts equivalent to a human eating multiple ounces of pure MSG at once. Not surprisingly, the mice showed ill effects, and alarming reports emerged that MSG could cause brain lesions, stunted growth, or nerve damage. These sensational findings grabbed headlines, and consumer advocates reacted swiftly.

By 1969, prominent activists like Ralph Nader were pushing to ban MSG in baby food, and major baby food manufacturers voluntarily pulled MSG from their products amid public outcry. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which had long classified MSG as “Generally Recognized As Safe,” launched a review under pressure. “No MSG” labels began appearing on restaurant windows and food packaging as a marketing badge of purity. The idea that MSG was a hidden harmful “chemical” had officially entered the public consciousness.

The trouble was, much of the anti-MSG science was deeply flawed. In one oft-cited experiment, subjects were given MSG on an empty stomach in large quantities – an approach almost guaranteed to cause transient discomfort in anyone, much like wolfing down too much salt or vinegar alone. Other trials failed to use proper blinding, so participants knew when they were ingesting MSG and might have imagined symptoms due to expectation or anxiety. Over the next few decades, as more rigorous research was conducted, the consensus in the scientific community coalesced: at normal dietary levels, MSG isn’t the bogeyman it was made out to be.

What Science and Regulators Say About MSG

So, is MSG actually safe to eat? According to toxicologists and health authorities around the world, the answer is yes. Monosodium glutamate has become one of the most exhaustively studied food additives in history. Hundreds of scientific studies – including controlled human trials – have failed to find evidence that MSG causes any widespread or consistent adverse effects. While a small subset of people might have a mild sensitivity and experience short-term symptoms if they consume a huge amount on an empty stomach, researchers have found no toxic or long-term health impact from normal MSG use. In fact, our bodies metabolize the glutamate from MSG in exactly the same way as the glutamate present naturally in foods like tomatoes or Parmesan cheese.

Regulators have taken note. The U.S. FDA maintains MSG on its list of approved food ingredients and states that MSG is safe when consumed at customary levels. International experts agree: the Joint expert committee of the World Health Organization has never found a reason to set an upper limit on MSG’s use, and the European Food Safety Authority affirms its safety within typical dietary intakes. In short, MSG is harmless – except, of course, for making your food taste delicious. “There is not one scientific paper to prove that it’s bad for you,” notes celebrated chef Heston Blumenthal, who calls the MSG scare “complete and utter nonsense”. The enduring belief that MSG is uniquely dangerous simply isn’t supported by science or medicine.

Fear, Flavor, and Fictions Fueled by Racism

If the science doesn’t support MSG as a dietary villain, why did so many people come to loathe and fear it? The answer lies not in biology, but in bias. The very name “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” points to the misconception’s insidious core: it singled out Chinese cuisine (and by extension, Chinese people) as suspect. This framing tapped into old Western prejudices portraying Asian food as unhygienic, exotic, or untrustworthy. As Korean-American chef David Chang observes, avoidance of MSG became “a cultural construct” – essentially a socially accepted excuse to distrust foreign cooking under the guise of health concerns. In plainer terms, it was ignorance and xenophobia masquerading as wellness.

Consider that Americans happily ate MSG for years in things like Campbell’s soup and KFC chicken without raising an eyebrow. Only when MSG was associated with Chinese restaurant cooking did it suddenly become a supposed health hazard. No one warned about an “Italian Pizzeria Syndrome” from the glutamate-rich parmesan on your pasta, or a “Mom’s Home Cooking Syndrome” from the umami in a pot roast. Yet Chinese restaurants were unfairly cast as vectors of a fake syndrome. “You know what causes Chinese Restaurant Syndrome? Racism,” the late Anthony Bourdain once quipped, cutting to the chase. His point: diners were quick to blame a “mysterious Oriential additive” for their post-meal discomfort rather than, say, overeating or simply the bias planted in their heads.

The targeting of MSG also dovetailed with a broader history of anti-Asian sentiment. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Chinese immigrant communities in the U.S. endured racist laws and slanders (from the Chinese Exclusion Act to lurid rumors about Chinese restaurant sanitation). The MSG myth arrived in that cultural context, making it easier for people to believe and propagate. Chinese-American restaurateurs bore the brunt of this stigma: they had to alter recipes, hang “No MSG” signs, and watch customers scrutinize their cuisine with undue suspicion. Meanwhile, predominantly white-owned food companies continued using MSG in snacks and frozen dinners with little fanfare or outrage, a telling double standard.

The myth wasn’t just bad science – it was racial scapegoating, and it caused real economic and reputational harm.

The Comeback: MSG’s Reputation Gets a Reboot

Today, MSG is undergoing a rehabilitation of sorts, as chefs and consumers alike wake up from the long-running moral panic. In recent years, prominent culinary figures and scientists have pushed back against the anti-MSG narrative. Chef David Chang has been vocal in defending the seasoning, noting that MSG is simply sodium and glutamate – “something your body produces naturally and needs to function” – and that multiple studies have failed to show it makes anyone sick. “It only makes food taste delicious,” he points out. Other food world luminaries, from cookbook author Fuchsia Dunlop to molecular gastronomy guru Heston Blumenthal, have called for MSG’s stigma to end, pointing out that demonizing this additive is both unscientific and unfair. Some trendy restaurants now openly sprinkle MSG like a gourmet ingredient, celebrating its umami-boosting powers.

Even the institutional record is being corrected. In 2020, Ajinomoto (the original MSG manufacturer) launched a public campaign to “reclaim MSG’s honor.” The company enlisted Asian-American celebrities in a cheeky video declaring that “MSG is delicious” and petitioned Merriam-Webster to change its entry for “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome”. The dictionary editors agreed to revisit the term, ultimately updating it to note that it’s dated and offensive – essentially an antiquated myth, not a real medical condition. Public opinion is slowly following suit: a 2022 survey found that younger consumers are far less likely to believe MSG is harmful compared to previous generations, and food products that proudly tout MSG or “umami” are gaining popularity.

It’s a remarkable turnaround for a seasoning once cast as a public enemy. While a kernel of the old fear still pops up now and then (often echoing outdated information), the broader trend is moving toward acceptance. Many people have come to realize what the science showed all along: that MSG is, at its core, just a useful flavor enhancer with an unjust bad rap. The real lesson is less about chemistry and more about cultural humility. As one food writer famously asked, “If MSG is so bad for you, why doesn’t everyone in China have a headache?” The obvious answer is that they don’t – and neither do the rest of us. It turns out, the only thing we truly had to fear about MSG was fear itself (and maybe missing out on some really tasty food).

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

📚 Sources + Further Reading

- BBC News – ’Chinese Restaurant Syndrome’ – what is it and is it racist? (Jan 16, 2020)

- The Guardian – Chinese restaurant syndrome: has MSG been unfairly demonised? (May 21, 2018)

- Science History Institute – The Rotten Science Behind the MSG Scare (Sam Kean, Distillations Magazine, 2020)

- Feather River Food Co-op – MSG: The Xenophobic Myth of “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” (2021)

- UW Medicine – Is MSG Unhealthy? Debunking the Myth (Right as Rain, 2022)

- The Harvard Crimson – Baby Food Manufacturers Will Suspend Use of MSG (Oct 27, 1969)

- The Guardian – If MSG is so bad for you, why doesn’t everyone in Asia have a headache? (Feb 19, 2015) (Jeffrey Steingarten quote)

- New England Journal of Medicine – Kwok, R.H.M. “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.” (Letter, 1968) [Origin of the term]

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)