Gut health vs. life-threatening peanut allergies: Why one viral story doesn’t equal a safe cure

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

Candi Frazier, known online as theprimalbod, recently shared a reel in which she discusses her experience with food allergies. The reel is built around an implied claim: that a person with a severe peanut allergy could potentially cure that allergy simply by “healing the gut” with diet changes.

As research into allergy treatments keeps advancing, let’s check those claims against the latest available evidence on the links between gut health and the course of food allergies.

Severe peanut allergy is usually persistent, and when tolerance does increase, it is either spontaneous in a minority of people or the result of carefully supervised immunotherapy using controlled doses of peanut, not generic gut‑health protocols.

This reel carries big implications for people living with life-threatening allergies. On the surface, Candi’s account reads like a simple cause‑and‑effect story: repair the gut and microbiome, and the immune system stops reacting. The concern is not whether this is a perfectly accurate account of her own journey, but how it lands with viewers. Candi describes herself as a board‑certified nutritionist, and by sharing this story without anchoring it in evidence or explaining where it does and doesn’t apply, she risks prompting someone with a genuine high‑risk allergy to think “maybe this will work for me” and to experiment on themselves, with potentially serious consequences.

Look for evidence: Health claims should be backed by scientific studies or data. Reliable public guidance is built from research that gives predictable, reproducible results in many people, not from one‑off stories.

“I was extremely allergic to peanuts [...] and I suffered with that for several years, not knowing that all I needed to do was fix my gut.”

The implied claim in the reel is that healing the gut can potentially cure allergies. Candi describes years of suffering from leaky gut, many food intolerances and allergies, including a severe peanut allergy that required an epinephrine auto‑injector. She then says that after removing grains and coffee from her diet and eating fermented foods, she can now eat all foods (including peanuts) without a problem.

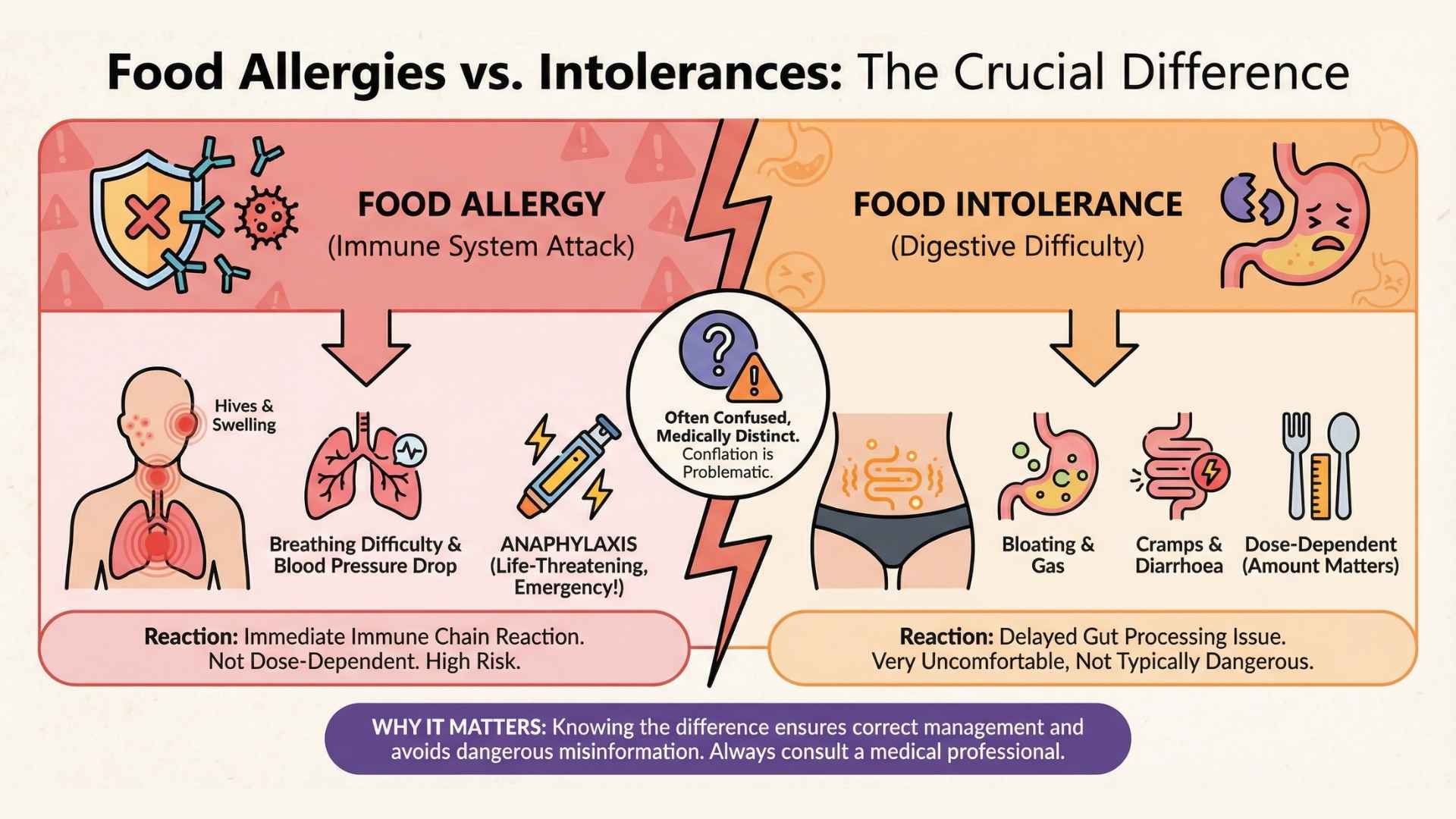

To understand how this stacks up against the evidence, it helps to start with detangling what severe peanut allergy actually is. As Candi mentions suffering from allergies and intolerances, let’s start with the difference between the two.

Food allergies and intolerances: what’s the difference and why does it matter?

A food allergy involves the immune system: the body produces antibodies against a food protein that is identified as a threat. When those proteins are encountered again, they can trigger a chain reaction leading to hives, swelling, breathing difficulty, drops in blood pressure, and, in some cases, anaphylaxis, which can be life‑threatening and requires emergency treatment.

In contrast, a food intolerance does not involve this kind of immune attack but rather will manifest itself in the gut; it usually reflects difficulty digesting or processing a food (for example, lactose intolerance due to low lactase enzyme), and while symptoms like bloating, diarrhoea or cramps can be very uncomfortable, they are not typically dangerous in the same way and are often dose‑dependent.

Unlike an intolerance to food, a food allergy can cause a serious or even life-threatening reaction by eating a microscopic amount, touching or inhaling the food” (American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology).

In her reel, Candi mentions her peanut allergy required her to carry an EpiPen, indicating that this was a severe allergy. Epinephrine auto-injectors are life-saving devices that are prescribed to “people who are at risk for or have a history of serious allergic emergencies” (source).

This is an important starting point, because what this suggests to the readers is that dietary changes could solve even severe allergies like IgE-mediated ones, meaning allergies triggered by the immune system. Among food allergies, peanut allergies are among the most serious, both in terms of persistence and severity of symptoms (source).

Studies on the natural history of peanut allergy agree that it seems to behave differently from other allergies such as cow’s‑milk or egg allergy, which are more often outgrown in early childhood (source, source). In most cohorts, only a minority of children outgrow peanut allergy by school age, and many remain allergic into adulthood. That background rate of acquired tolerance is real (source), but relatively low, and is not tied in the literature to any particular “gut healing” diet.

So what actually increases tolerance in a predictable way?

Treatments focus on building tolerance, rather than ‘curing’ allergies

Controlled clinical trials of peanut oral immunotherapy (OIT) in children and adults use tiny, gradually increasing doses of peanut protein, given under strict medical supervision, to train the immune system to cope with accidental exposures (source). This is absolutely not something to do without supervision.

These studies show that many participants can reach a point where they tolerate much larger amounts of peanut without reacting, but they also report possible side‑effects and the need for ongoing maintenance dosing. On the strength of this evidence, professional societies such as BSACI now endorse standardised OIT products (like Palforzia) as an option in specialist settings, while still recommending strict avoidance and emergency medication as the foundation of everyday management. These treatment options are still being researched, but seem to show promising results. On the other hand, none of these guidelines list “gut healing” diets as a recognised treatment for peanut allergy.

Food allergies and the gut microbiome

In recent years, researchers have found growing evidence on the role played by the gut microbiome and its impact on various aspects of health and well-being. When it comes to food allergies, the gut and microbiome are not irrelevant; they are also an active research frontier.

Studies comparing people with peanut allergy to non‑allergic controls often find distinct microbial “signatures” and differences in microbial diversity (source, source). Some work even suggests that certain microbiome patterns may predict who does better on peanut immunotherapy (source). This review also discusses how a disrupted gut barrier and dysregulated microbiota might make it easier for food proteins to drive sensitisation and inflammation, and proposes that modifying these factors could one day be part of prevention or treatment strategies.

But there is a crucial gap between these mechanistic insights and the reel’s suggested promise: to date, no robust clinical trials show that removing foods like grains and coffee, and adding fermented foods can switch off established, IgE‑mediated peanut allergy such that people can safely eat peanuts without supervised desensitisation.

Final take away

This kind of story can be compelling and might well be true for the person telling it, but a fact‑check is not about verifying one individual’s experience; it is about whether that experience (shared with a large number of followers) can safely inform advice for everyone else.

Anecdotes, especially on social media where many people now seek health and nutrition guidance, cannot be the basis for public recommendations about food allergies. Individual allergy profiles differ in immune markers, co‑existing conditions and how they evolve over time, and it remains very hard to predict how severe a future reaction will be (source). Because of this variability and the potential seriousness of accidental exposures, expert guidance is built on controlled oral food challenges, long‑term follow‑up and clinical trials, not on single cases; one person’s “healing” does not show that others with severe, IgE‑mediated peanut allergy can safely copy the same diet and reintroduce peanuts. The gut and microbiome matter, but there is no validated, diet‑only protocol that turns a severe allergy into full tolerance.

Candi does not directly instruct viewers with a documented allergy to follow her approach, so the video can be framed as “just sharing a story,” yet in a landscape where nutrition misinformation already undermines trust in clinicians, that framing still carries risk. If someone who is wary of medical advice hears this from someone who is presented as a board‑certified nutritionist, they may feel more confidence in this anecdote. For someone with a history of anaphylaxis, the gap between “my gut feels better” and “my immune system no longer reacts dangerously to peanuts” can be the difference between safety and a life‑threatening reaction.

We have contacted Candi Frazier and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources:

- American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology (2025). “Food Intolerance Versus Food Allergy.”

- Burks W. (2003). “Peanut allergy: a growing phenomenon.” Jeong, K. & Lee, S. (2023). “Natural course of IgE-mediated food allergy in children.”

- Turcanu, V., et al. (2003). “Characterization of lymphocyte responses to peanuts in normal children, peanut-allergic children, and allergic children who acquired tolerance to peanuts.”

- Hunter, H., et al. (2025). “Oral Immunotherapy in Peanut-Allergic Adults Using Real-World Materials.”

- BSACI (2017). “Peanut and Tree Nut Allergy.”

- Li, S. et al. (2025). “Investigation of gut microbiota in pediatric patients with peanut allergy in outpatient settings.”

- Chun, Y., et al. (2023). “Longitudinal dynamics of the gut microbiome and metabolome in peanut allergy development.”

- Wright, K. (2025). “Gut Microbiome Predicts Success of Peanut Immunotherapy.”

- Poto, R., et al. (2023). “The Role of Gut Microbiota and Leaky Gut in the Pathogenesis of Food Allergy.”

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)