Does Tap Water Really 'Dehydrate' You? The Viral Claim Checked Against the Evidence

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

In a widely shared Instagram reel, with nearly 600 000 views, popular US-based wellness influencer Gubba Homestead claimed that the public has been “lied to about water.”

In the video, they state that “most bottled and tap water is dead water,” arguing that because it is “chlorinated, sterilised and often packaged in plastic,” drinking it “dilutes your electrolytes” and can leave you “more dehydrated.” The post also suggests that electrolyte powders and sports drinks are promoted to keep consumers “hooked and paying,” while claiming that previous generations hydrated better through foods and drinks such as raw milk, bone broth, fermented beverages and herbal teas. The reel contrasts these ideas with modern advice to drink “eight glasses a day” of plain water.

In this fact-check, we look at the science behind this popular recommendation, checking whether the evidence supports that ‘modern water’ can leave you more dehydrated.

While hydration needs do vary and fluids from food contribute to overall intake, there is no evidence that treated drinking water depletes electrolytes or causes dehydration in healthy people. The claim mixes partial truths about hydration with unsupported assertions, creating a misleading narrative that undermines trust in safe, modern drinking water.

Claims about hydration can influence everyday health choices. When misleading ideas spread, people may avoid safe drinking water or spend money on unnecessary supplements. Clear, evidence-based guidance matters because access to clean water is one of the most important public health advances of the modern era.

Question viral content: If something seems too outrageous or extreme, it may be misleading or false.

Where do we get water from and what is the recommended intake?

Water is essential for human life and occurs naturally across the planet. Around 71% of the Earth’s surface is covered by water, with oceans holding about 96.5% of all surface water. However, only around 2.5% is freshwater, which is the type needed to sustain human, animal and plant life. Most freshwater is locked away in ice caps, glaciers, or underground. Only a small proportion exists as surface fresh water, and just 0.49% is found in rivers, which are one of the main sources used for human consumption (source).

The human body is composed of approximately 60% of water by body weight in adult males and around 50% to 55% in adult females, due to differences in body fat proportion. Water is a main component of blood, digestive juices, urine and faeces. Adults lose water continuously through respiration, sweating and excretion. Respiratory water loss alone averages about 250 to 350 mL per day in sedentary individuals and increases substantially with physical activity, altitude and environmental conditions.

These losses need to be replaced to keep the body functioning normally (source).

Hydration needs differ between individuals and depend on factors such as:

- Body size

- Age

- Gender

- Activity level

- Climate

- Diet

- Fluid intake from food

- Pregnancy or breastfeeding status

- General lifestyle

These factors explain why there is no single, universal water requirement (source, source).

How much water is recommended to drink every day?

Public guidance such as the NHS Eatwell Guide recommends that people aim to drink 6–8 glasses of fluid per day. However, this is intended as a general guideline, not a strict rule. Actual requirements vary based on many factors previously mentioned.#

Claim 1: Most tap and bottled water is “dead” because it’s chlorinated, sterilised, or in plastic.

Fact-check: The term “dead water” has no scientific meaning. It implies that treated water lacks health value, but there is no evidence to support this.

In the UK, tap water is disinfected using chlorine to kill harmful pathogens and prevent waterborne disease. This public health measure has saved millions of lives worldwide. Chlorine levels in drinking water are carefully regulated and considered safe, and there is no evidence that chlorinated or filtered water harms hydration or health (source).

Claim 2: Drinking plain water dilutes electrolytes and causes dehydration

Fact-check: This claim overlooks the body’s natural regulatory systems that maintain electrolyte balance, leading to oversimplified conclusions that don't apply to most healthy people.

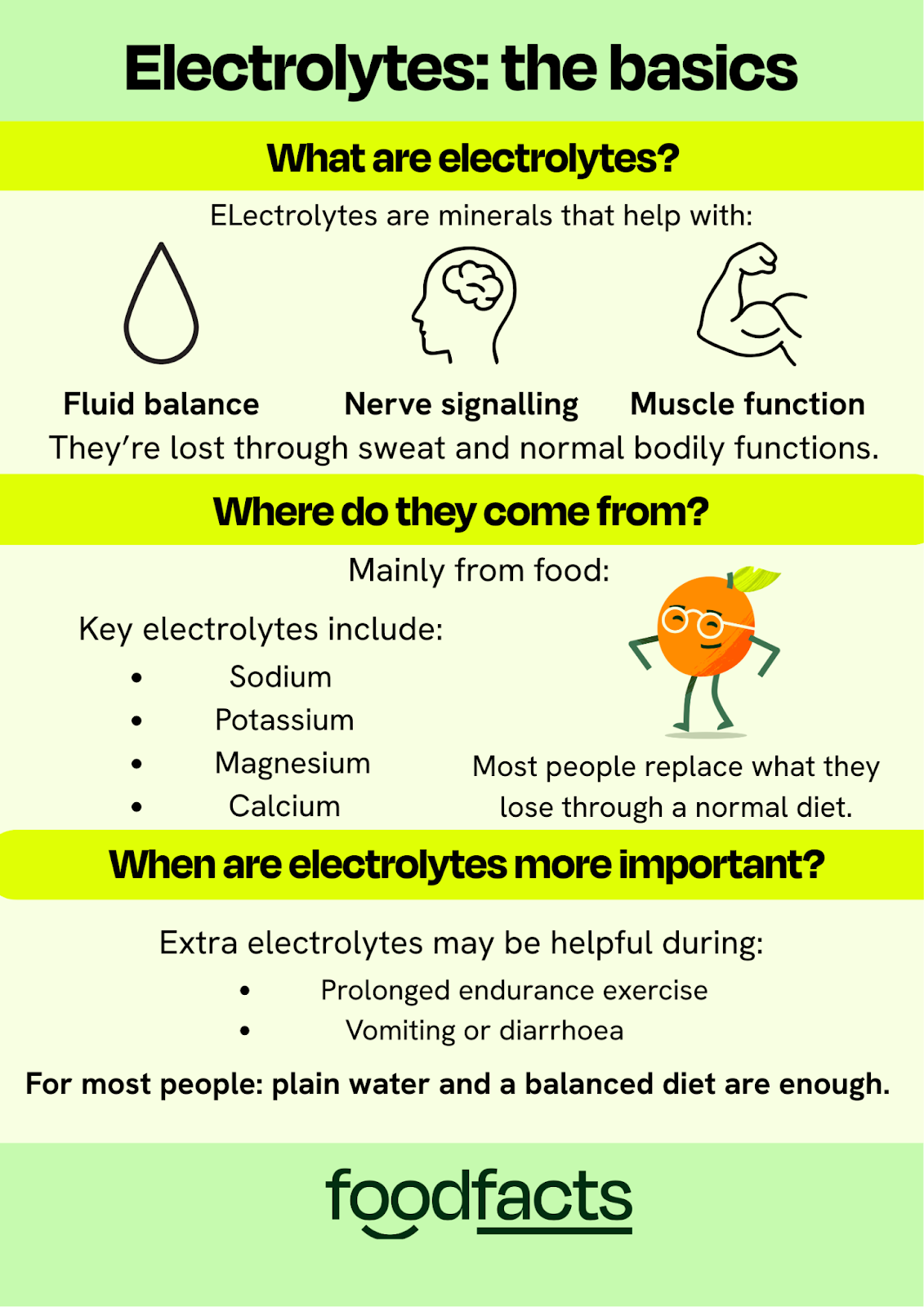

Electrolytes play an important role in fluid balance, nerve signalling and muscle function, and they are lost through sweat and everyday bodily processes. For most people, these minerals are replaced naturally through food and drink.

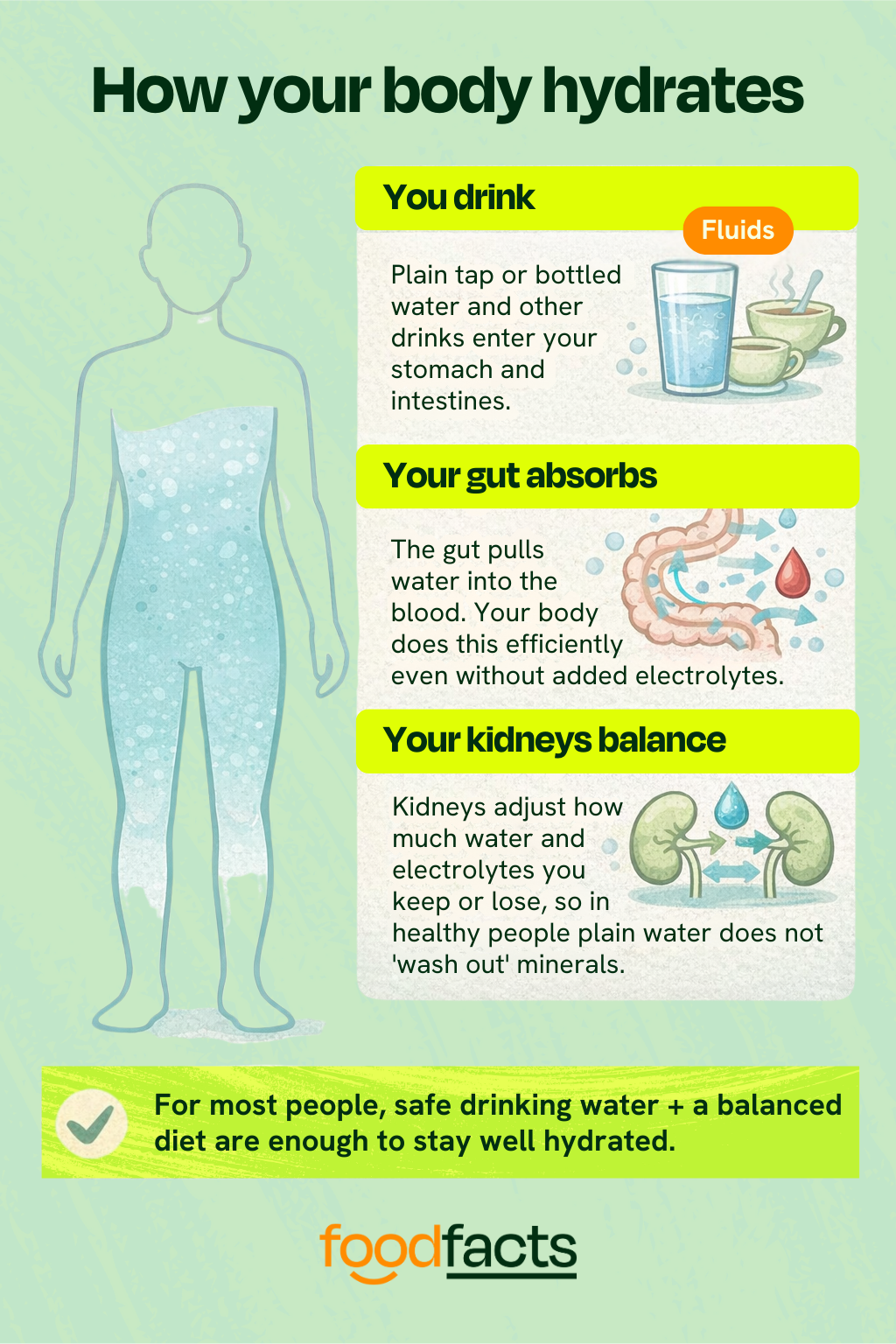

While mineral content varies between water supplies, key electrolytes such as sodium, potassium, magnesium and calcium are mainly obtained from food, rather than plain drinking water. The body carefully regulates fluid and electrolyte balance through the kidneys, the thirst response and hormones such as vasopressin. In healthy people, these systems keep electrolyte levels within a normal range across different levels of fluid intake. Drinking plain water does not dilute electrolytes to harmful levels. The body efficiently regulates hydration by excreting excess water and maintaining stable electrolyte concentrations. Claims that water alone causes dehydration are therefore exaggerated and commonly misrepresented online (source, source).

Electrolyte imbalances are more likely in specific situations, such as prolonged endurance exercise or illness involving vomiting or diarrhoea. In these cases, electrolyte drinks or medical rehydration solutions can be helpful. For most people, however, plain water and a balanced diet are enough (source, source).

Claims about water leading to dehydration or being “bad for you” are popular on social media platforms. As Dr Idz mentioned in a video debunking similar claims back in 2024, they often rely upon a lack of understanding of physics and chemistry concepts, as well as nutrition. He explains:

“Your body is efficient at absorbing water on its own: the intestines are designed to draw water in through osmosis, even without added electrolytes. Now electrolytes do help in maintaining fluid balance. So in situations like intense running or bad diarrhoea, topping up on electrolytes will be needed. But remember, we consume plenty of electrolytes through our normal diet, so the majority of us can drink plain water and be perfectly hydrated.”

Claim 3: Electrolyte powders and sports drinks aren’t necessary and are pushed to keep people dependent

Fact-check: Electrolyte powders and sports drinks can be useful during intense or prolonged physical activity, or when illness causes significant fluid and salt loss.

Outside of these situations, most people do not need them. Many nutrition experts agree that plain water is sufficient for everyday hydration, with electrolytes coming from a balanced diet. Often sports drinks are marketed far beyond their limited practical use and frequently contain added sugars. For the general population, routine use offers no clear health benefit (source).

Claim 4: The “8 glasses of water a day” rule is wrongly presented as necessary

Fact-check: The claim uses “8 glasses a day” as a general benchmark, but this is an oversimplification of health advice and not evidence based.

Experts describe it as a simple guideline rather than a strict scientific requirement. Drinking adequate fluids is essential for hydration, but the exact amount varies between individuals. Public health guidance recognises that hydration needs vary. In the UK, fluids such as water, milk, tea and coffee all count toward daily intake, with higher needs during heat, illness or physical activity (source).

It’s also important to note that fruits, vegetables and soups contribute significantly to hydration. For most people, thirst and urine colour (pale yellow) are reliable indicators. There is no single amount that applies to everyone (source).

Claim 5: Our ancestors hydrated better through mineral-rich foods and drinks

Fact-check: Historically, people consumed broths, herbal infusions, fermented drinks and raw milk, which provided fluids and nutrients. However, these practices were largely driven by the lack of consistently safe drinking water, not superior hydration knowledge.

Promoting raw milk as a hydration source is especially concerning, as it is associated with several health risks, including bacterial infections. This fact-check examines the evidence behind public health guidance on raw milk consumption, especially among vulnerable populations like children or pregnant women.

Boiling and fermenting liquids helped reduce the risk of waterborne disease. In contrast, modern water treatment and sanitation have dramatically improved access to safe drinking water and reduced infectious disease. While food-based hydration played a role historically, it was not healthier or more effective than today’s access to treated drinking water (source, source).

Final takeaway

The idea that we’ve been “lied to” about water is misleading. While the “eight glasses a day” rule is not a strict guideline, drinking tap or bottled water does not cause dehydration in healthy people. Hydration depends on individual needs, diet, and lifestyle, with fluids from food and other drinks playing an important role. Electrolyte drinks have specific uses but are unnecessary for most people and often over-marketed. The evidence is clear: safe drinking water, a balanced diet, and listening to your body are the most reliable ways to stay hydrated.

We have contacted Gubba Homestead and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources:

- U.S. Geological Survey, Water Science School. (2019). “Distribution of water on, in, and above the Earth.”

- European Food Safety Authority. (2010). “Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Water.”

- Ribel, S. & Davy, B. (2013). “The Hydration Equation: Update On Water Balance and Cognitive Performance.”

- Armstrong, L. (2021). “Rehydration during Endurance Exercise: Challenges, Research, Options, Methods.”

- NHS. (2023). “Diarrhoea and vomiting.”

- NHS. (2025). “The Eatwell Guide.”

- Drinking Water Inspectorate. (n.d.). “Chlorine.”

- NHS. (2023). “Water, drinks and hydration.”

- Hartemann, P. & Montiel, A. (2025). “History and Development of Water Treatment for Human Consumption.”/

- Munoz-Urtubia, N. et al. (2023). “Healthy Behaviour and Sports Drinks: A Systematic Review.”

- World Health Organization. (2023). “Drinking‑water.”

- Perrier, T. et al. (2020). “Hydration for health hypothesis: a narrative review of supporting evidence.”

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)