Snickers vs. Apple and Peanut Butter: Why Comparing Sugar Content Alone Is Dangerously Misleading

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

A series of recent videos by Candi Frazier from “The Primal Bod” show the influencer claiming that “insulin blocks fat burning”, that humans are “supposed to eat meat because that's what our species is supposed to eat”, and that an apple and peanut butter are equal to eating a Snickers bar (for our blood sugar).

These statements might resonate with many people who are trying to lose weight or manage blood sugar, but they also risk oversimplifying how human metabolism works. Does insulin block fat burning? Are humans supposed to eat ‘lots’ of meat? Is an apple with peanut butter the same as a Snickers bar? Let’s check what the scientific evidence is, where the nuance is lost and why it matters.

Insulin is not an enemy: it is an essential hormone that helps the body use and store energy, and its natural effect of temporarily reducing fat burning after meals is part of normal physiology, not a reason to fear carbohydrates or fruit. Because humans evolved as adaptable omnivores, health can be supported both with and without meat, as long as diets are well-planned and nutritionally balanced. This means that the real focus should be on the overall quality of what we eat, not on rigidly eliminating certain foods. Moreover, comparing a Snickers bar and an apple with peanut butter is highly misleading; even though they may have similar calories, they differ in their glycemic load, fibre content, and overall nutrient density, so they are not equivalent in terms of health impact.

This type of message can lead people to unnecessarily restrict entire food groups, develop fear around healthy foods, or follow diets that are difficult to sustain long term. Nutrition advice should help people build healthier relationships with food, not create confusion or fear.

Check credentials: Look into the author’s credentials and expertise on the subject. Unfortunately, social media can amplify the voice of influencers who oversimplify or misrepresent scientific evidence and sometimes promote unnecessarily restrictive eating patterns.

Claim 1: Insulin blocks fat burning

Fact-check: Even though the claim that insulin blocks fat burning is technically correct (for a bit), the explanation in the video is incomplete and misleading.

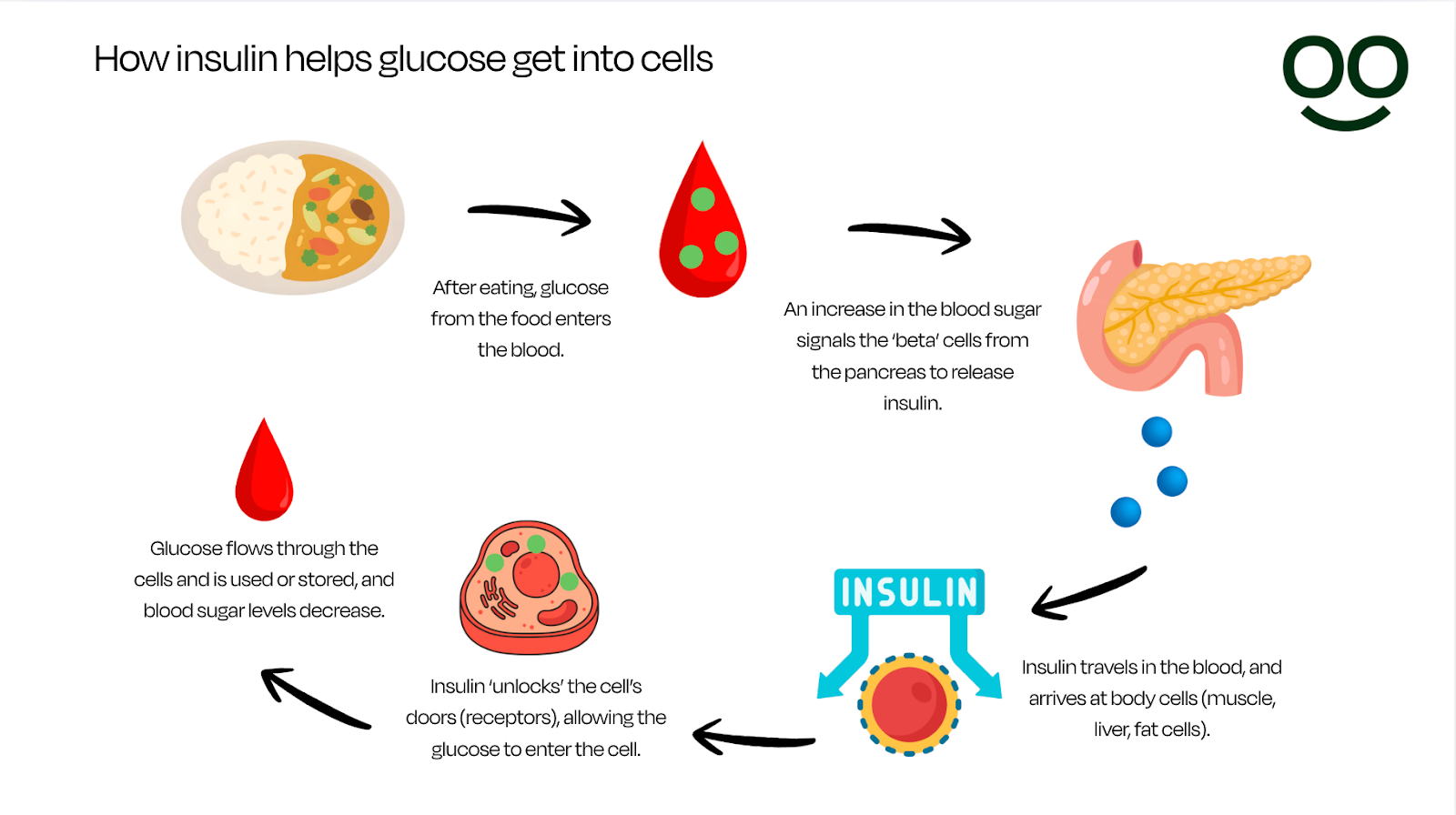

Let’s see it this way: Insulin is like a key that helps the body use glucose from food for energy. When we eat a meal that contains carbohydrates, and the food is digested, glucose enters the blood. An increase in glucose in the bloodstream triggers the ‘beta’ cells in the pancreas to release insulin, "unlocking" the cells so glucose can enter them.

Insulin then helps move glucose from blood into cells and signals the body to store energy. When insulin levels are elevated, fat burning temporarily decreases. However, this is normal physiology and happens multiple times per day in a healthy metabolism (source, source).

Should we worry about blood sugar spikes?

In her videos, Frazier argues that because insulin blocks fat burning, people who want to lose weight should avoid foods that raise blood sugar and insulin as much as possible, regardless of the food source. However, this argument misses important physiological context.

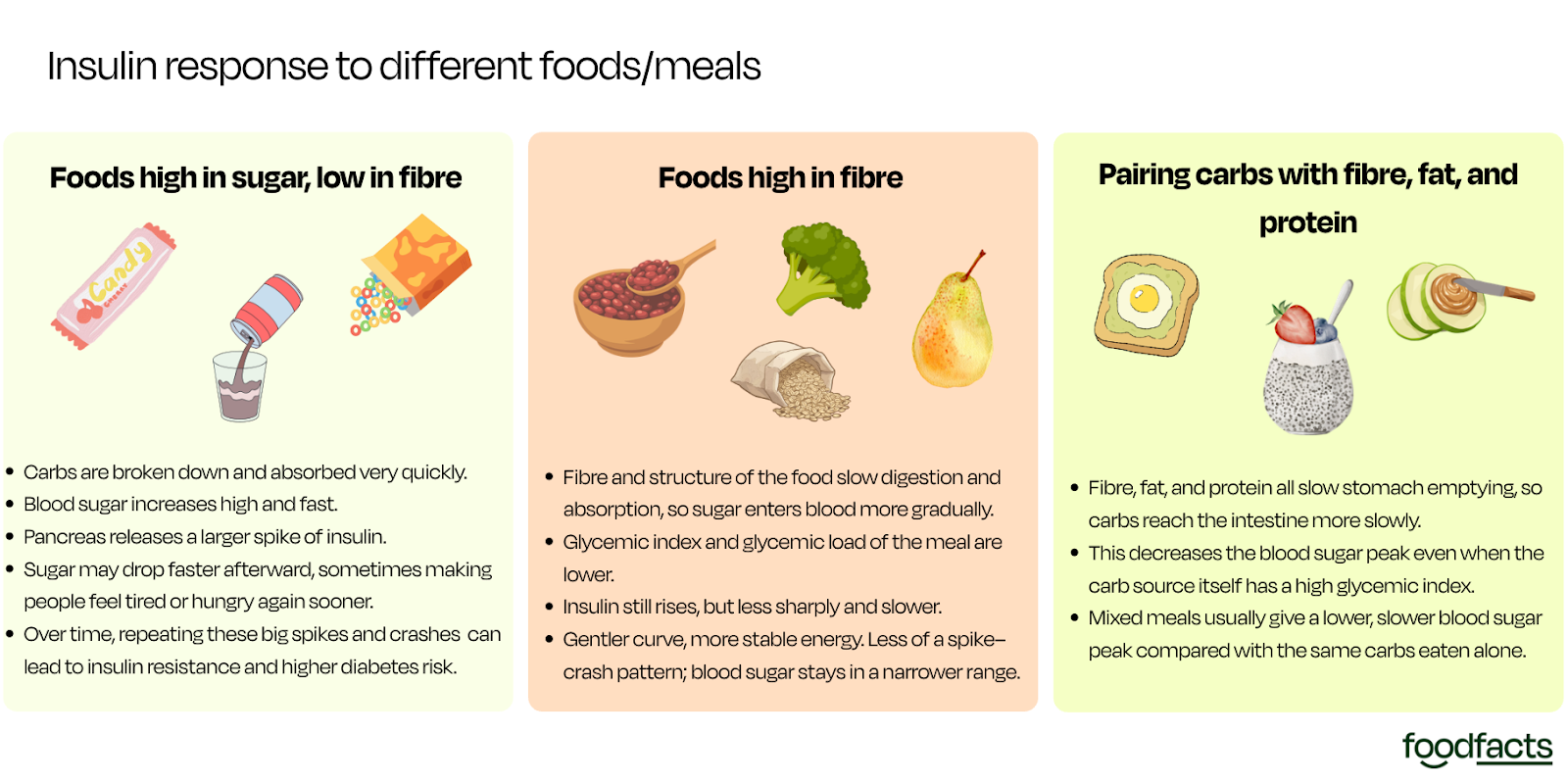

Not all rises in blood sugar are harmful. After eating, blood glucose normally increases and then returns to baseline as insulin helps move glucose into cells. This is a healthy response. However, large or prolonged blood sugar spikes that occur frequently over time can be harmful, particularly in people with insulin resistance or diabetes. Chronically elevated glucose levels are also linked to increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, nerve and kidney damage, and chronic inflammation (source).

This is why maintaining glucose levels within healthy ranges matters. The goal, however, is not to eliminate glucose rises entirely, which is highly unsustainable and unnecessary, but to reduce excessive spikes by eating fibre-rich foods, including protein and healthy fats in meals, staying physically active, being mindful of food portions, getting adequate sleep, managing stress, and limiting frequent intake of highly processed sugary foods.

What happens if someone eats only protein and fats?

Glucose is the primary energy source for the brain, red blood cells and working muscles, and blood glucose needs to be within a range to sustain normal metabolism and survival (source). In the absence of sufficient carbohydrate intake, such as in very low-carbohydrate or ketogenic diets, the body adapts in two main ways:

- The liver produces glucose through a process called gluconeogenesis, using other sources to get the glucose from, such as amino acids (from protein), glycerol (from fats) and lactate.

- Fat breakdown increases, producing ketone bodies that can partially fuel the brain and other tissues. This specifically is what gives the “keto diet” its name.

So even if someone eats only protein and fats, the body still maintains blood glucose levels, it simply produces glucose internally instead of getting it from carbohydrates. Importantly, insulin does not disappear on a protein and fat diet. Protein also stimulates insulin release, because insulin is needed not only for glucose control but also for amino acid uptake and tissue repair (source).

Who may benefit from lower-carbohydrate diets?

Lower-carbohydrate diets can be helpful for some people, particularly individuals with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes, people with insulin resistance and some people aiming for weight loss who find lower-carb diets easier to maintain.

However, low-carb diets are not appropriate or sustainable for everyone, and long-term success depends more on diet quality and long-term adherence than on carbohydrate amount alone (source, source). It is always recommended to consult a healthcare professional, such as a registered nutritionist/dietitian, for better advice on the type of eating pattern that aligns better with individual circumstances.

Claim 2: Humans are “supposed to eat meat, because that's what our species is supposed to eat”

Fact-check: Frazier argues that humans are meant to eat meat because this is what our species evolved to eat. However, scientific evidence supports humans as adaptable omnivores, and not necessarily meat‑eaters, and shows that health is compatible with both meat‑containing and meat‑free diets when they are well planned.

Even though meat has played an important role in human evolution, humans evolved as omnivores who consumed both plant and animal foods depending on availability. Archaeological and anthropological evidence shows early humans ate meat, but also roots, tubers, fruits, nuts, seeds, and later grains and legumes (source).

Modern evidence shows people can stay healthy on diets with or without meat, provided nutritional needs are met. A recent systematic review comparing adults consuming plant-based diets with meat-eaters, mainly from studies conducted in Europe, North America and parts of South/East Asia, found that plant-based diets generally provided higher intakes of fibre, polyunsaturated fats, folate, magnesium, and vitamins C and E, nutrients associated with improved cardiovascular and metabolic health.

However, the review also found that plant-based eaters may have lower intakes or status of nutrients such as vitamin B12, vitamin D, iron, zinc, iodine and calcium, meaning planning is needed to avoid deficiencies.

At the same time, the review highlights a common issue in meat-eating populations: low fibre intake. Insufficient fibre intake is linked to increased risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, colorectal cancer, and poorer gut health.

In other words, both meat‑containing and meat‑free dietary patterns have potential strengths and weaknesses. Health outcomes depend less on whether meat is included and more on overall diet quality and nutrient balance (source, source).

Claim 3: An apple and peanut butter are equal to eating a Snickers bar

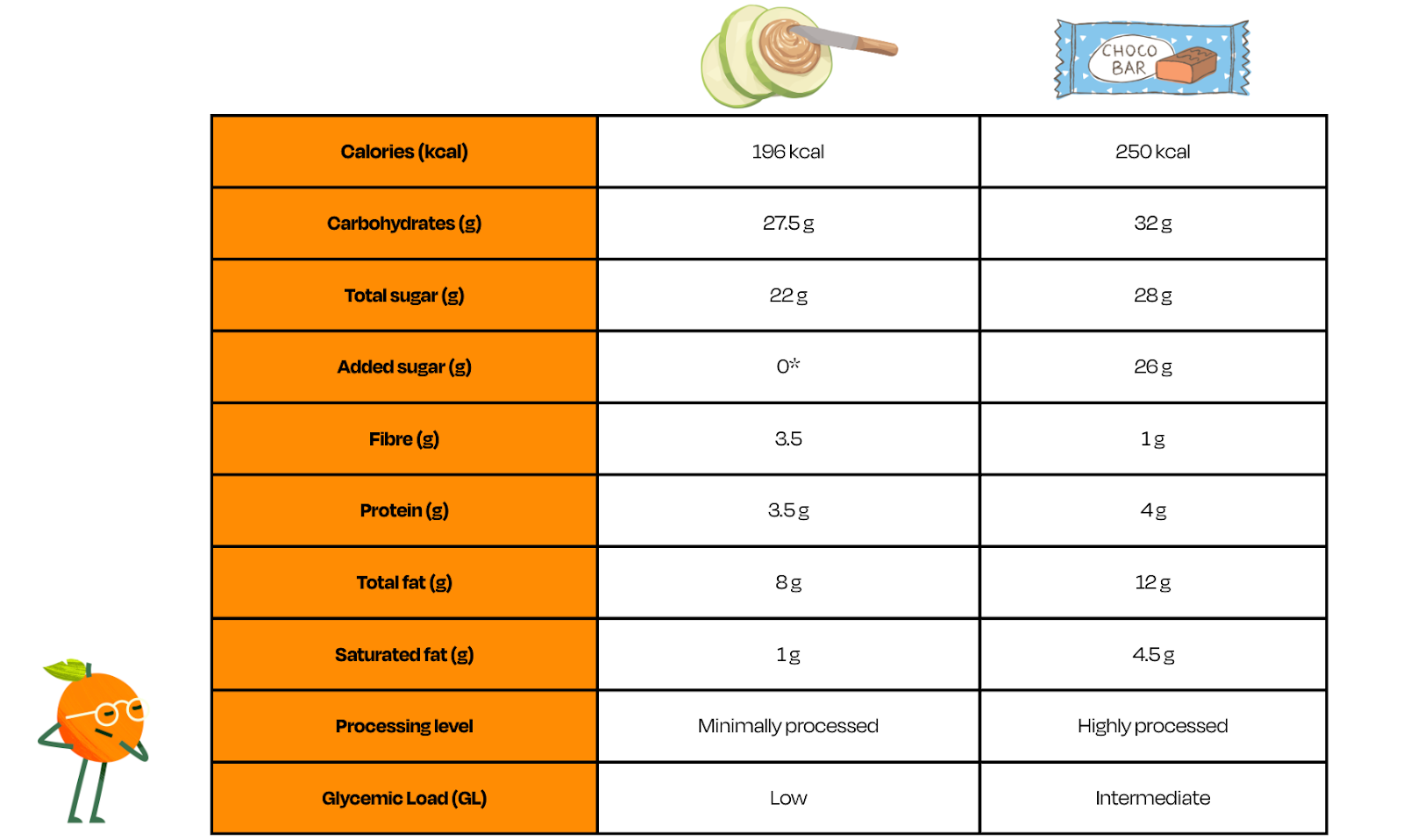

Fact-check: In one comparison, Frazier suggests that eating an apple with peanut butter is essentially the same for blood sugar as eating a Snickers bar. This claim is misleading when taking into account glycemic impact, satiety, and long‑term health associations.

This comparison is also an example of a false equivalence, which is when two items which aren’t comparable in a meaningful way are presented together. In this case, the comparison evaluates both foods almost exclusively through their sugar content while ignoring broader nutritional profiles. An apple with peanut butter is a nutrient-dense snack that provides fibre, vitamins, minerals, and healthy fats, while a Snickers bar is a highly processed product, high in added sugars and saturated fats, with little fibre or micronutrient contribution. Comparing them based on their sugar content only overlooks the difference in how foods affect appetite, diet quality, and long-term health.

To measure how foods containing carbohydrates affect blood sugar, the Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load are used. Glycemic index measures how quickly a food raises blood sugar, but glycemic load considers both speed and portion size.

Whole fruits have a relatively low glycemic load because fibre slows digestion and absorption, and the sugars present in whole fruit are bound within this fibre-rich structure. Peanut butter adds fat and protein, which further slows glucose absorption and can increase satiety, especially if it does not contain added sugars (source). A Snickers bar, by contrast, combines added sugar (‘free sugar’) and fat in a highly processed, energy-dense form with little fibre, and will likely cause a higher blood sugar spike.

In fact, data compiled for the glycemic load of different foods show that the average glycemic load of a Snickers bar is about 18 (intermediate impact), whereas a medium apple has a glycemic load of around 6 (low impact) (source, source). Accompanying the apple with peanut butter would, as mentioned, likely decrease further the glycemic load of the apple.

Bottom Line

Insulin is not the enemy; it is an essential hormone that allows us to use and store energy safely. The real question is not how to avoid insulin entirely, but how to build dietary patterns that support stable energy levels, metabolic health, and sustainable eating habits. Blood glucose naturally rises after meals, and in healthy metabolism it returns to normal levels shortly after. These temporary increases are expected and part of normal physiology. Problems arise when blood sugar remains chronically elevated, as in insulin resistance or diabetes.

Glucose responses also vary widely between individuals and are influenced by many factors, including meal composition, fibre and protein intake, physical activity, sleep, stress, and overall metabolic health. In practice, focusing on balanced meals and reducing frequent intake of calorie dense, highly processed foods matters far more for long-term health than fearing fruit, carbohydrates, or normal insulin responses.

We have contacted Candi Frazier and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources

- foodfacts.org (14 November 2024). The Glucose Goddess on coffee, milk, and blood sugar levels

- foodfacts.org (16 September 2025). The surprising reality about blood sugar spikes (it’s not what you think)

- Wilcox G. (2005). “Insulin and insulin resistance.”

- Norton, L., et.al. (2022). “Insulin: The master regulator of glucose metabolism.”

- Blaak, E., et.al. (2012). “Impact of postprandial glycaemia on health and prevention of disease.”

- Mergenthaler, P., et.al. (2013). “Sugar for the brain: the role of glucose in physiological and pathological brain function.”

- James, H., et.al. (2017). “Insulin Regulation of Proteostasis and Clinical Implications.”

- Snorgaard, O., et.al. (2017). “Systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary carbohydrate restriction in patients with type 2 diabetes.”

- Bragazzi, L., et.al. (2024). “We Are What, When, And How We Eat: The Evolutionary Impact of Dietary Shifts on Physical and Cognitive Development, Health, and Disease.”

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (2025). “Position Paper on Vegetarian and Vegan Diets.”

- Neufingerl, N., et.al. (2021). “Nutrient Intake and Status in Adults Consuming Plant-Based Diets Compared to Meat-Eaters: A Systematic Review.”

- Atkinson, F., et.al. (2021). “International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values 2021: a systematic review.”

- Harvard Medical School (2015). “Glycemic index and glycemic load for 100+ foods.”

- Linus Pauling Institute (nd). “Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load.”

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)