Why saying that raw salad is as dangerous as raw milk misses key context

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

Social media thrives on analogies, and raw milk is often compared with other foods like salads or ice cream to argue that it is unfairly demonised. Ann Bennett recently questioned why raw milk is singled out in media coverage or by health professionals, when all foods carry risks, while Paul Saladino has claimed that eating salad with raw spinach or lettuce is “274 times more dangerous” than drinking raw milk.

These comparisons suggest that public‑health guidance that emphasises the risks associated with raw milk is biased or exaggerated. This fact‑check analyses how food‑safety risks and guidance are actually derived, and whether these popular comparisons are supported by the available evidence.

Public‑health agencies compare foods using structured risk assessment, looking at severity, likelihood per serving, who is exposed, and whether safer alternatives exist, rather than just total case counts. By these criteria, unpasteurised milk causes far more illness and severe outcomes per serving than pasteurised dairy and many other everyday foods, especially in children and pregnant women. The claim that salads are 274 times more dangerous cherry picks available data by focusing on one single metric (total number of illnesses reported), and ignoring factors such as how many people actually consume salads, which are key to determining risk, and thus downplaying well‑documented dangers.

Raw‑milk infections are relatively rare in absolute numbers but disproportionately affect children and pregnant women and can lead to severe outcomes such as kidney failure, miscarriage or stillbirth. At the same time, surveys show that many adults do not fully understand these risks, while raw‑milk promotion on social media is growing. When people make decisions based on content that inflates raw‑milk benefits and minimises its risks, they may unknowingly accept a much higher chance of serious, preventable harm; clear, evidence‑based information can help avoid these consequences.

Transparency matters. Data is data, but the way it’s interpreted can vary and lead to flawed pictures. When you see bold numbers, always check the source.

Transparency and informed choice

Ann Bennett makes an important point when reacting to the recent tragedy in which a pregnant mother lost her unborn baby after her toddler became ill from raw milk: transparency must be prioritised alongside safe handling so that people can make informed choices. This is very much aligned with our mission at Foodfacts.org. Transparency here refers to honesty about how foods are produced, which pathogens they can carry, how often they cause illness, how severe those illnesses are, and which groups are at greater risk (for example pregnant women, infants, older adults and people with weakened immune systems).

Public‑health guidance emphasises that no food is risk free, but it highlights particular risks where they are higher or consequences more severe (such as Listeria in pregnancy or E. coli in undercooked meat or raw leafy vegetables). In her post, Ann raises the question: if many foods carry risks, why is raw milk singled out as dangerous? The answer lies in how risk is actually calculated in public health, which the “all foods have risk” narrative on social media can detract from.

How risk is assessed in practice

Public‑health agencies use a structured risk analysis process to inform how to talk about food safety issues. This process explains why raw milk is treated as a “high‑risk food” in guidance, even though other foods can also cause illness.

According to the UK Food Standards Agency (FSA), food‑safety decisions follow a formal risk analysis framework with three distinct parts: risk assessment, risk management and risk communication. Risk assessment is carried out by scientific experts who identify hazards (for example Campylobacter, E. coli, Listeria) and estimate the potential risk to health by combining two key elements:

- The severity of harm, for example mild gastroenteritis vs miscarriage or kidney failure;

- The likelihood that the food will make people ill, for example how much contamination is present, how often the food is eaten, and who is eating it.

Public‑health agencies do not stop at counting how many people get sick in total from a food. They assess “risk per serving” to identify the foods that are most likely to cause severe illness, and examine the causes of infections to promote safer practices. The situation would be similar if we were trying to assess transport safety: looking only at the number of road deaths versus plane crashes would not be enough data. To understand which mode of transport is safer, we need to consider exposure (how many journeys), severity of outcomes and the benefits each offers; the same applies when comparing foods.

Why this differs from “all foods carry risk”

On social media, the conversation looks very different. Posts generating engagement often emphasise “no food is risk free” and point out that salads, ice cream and many other foods have caused outbreaks, placing them rhetorically on an equal footing with raw milk. In theory, this sounds balanced. In practice, the comparison typically drops the key public‑health questions above.

Several patterns shape risk perception here:

- Repetition and algorithms: repeated reels of people drinking raw milk safely, or saying “my family has drunk it for years and we’ve never had an issue,” normalise the behaviour and make severe outcomes appear rare or exaggerated.

- Emotional framing: adversarial messages like “government/public health agencies don’t really care about your health” pull attention away from measured risk assessments.

This narrative ignores risk per serving and who is most at risk: key elements used in formal risk assessment to inform risk management measures (such as pasteurisation requirements, cooking advice or pregnancy‑specific guidance) and risk communication.

This environment makes it much harder, especially for parents, to weigh claims that “raw milk is nourishing and healing” against official guidance telling them not to give it to young children or to avoid it in pregnancy. Risk becomes a matter of which story feels more trustworthy, rather than which food actually causes more serious illness per consumer.

What the data actually show about raw milk

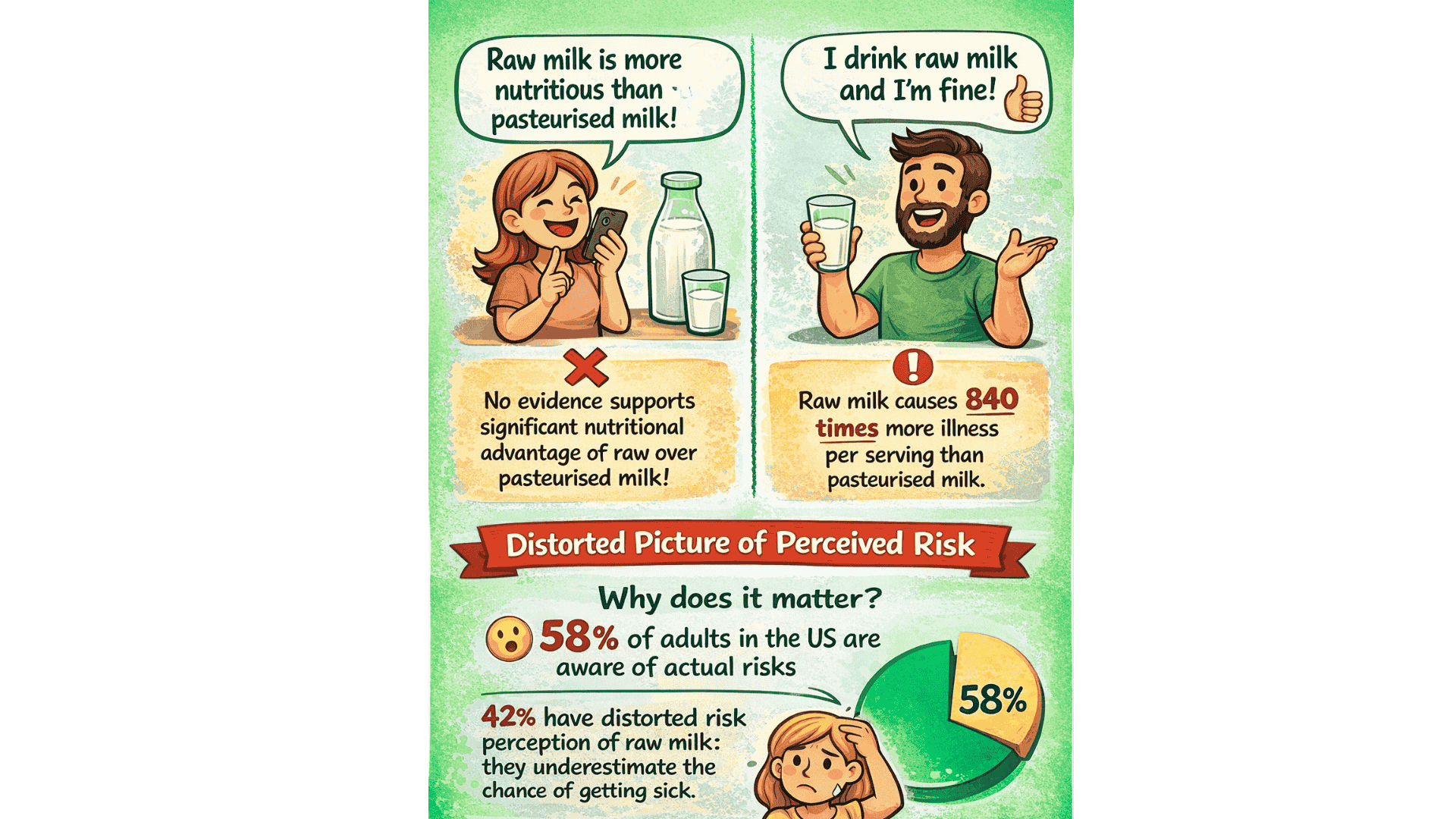

Social media can distort risk in two directions at once: by downplaying dangers and by exaggerating benefits that are not supported by solid evidence.

Let’s start with what the data shows about real-life complications that arise from raw milk consumption. Raw milk can carry pathogens like Campylobacter. Campylobacter infections are the most common cause of bacterial gut illness worldwide and make up a large share of all stomach and intestinal infections. Researchers note that raw milk is inherently risky, “because no treatment has been used to inactivate pathogens.” On the other hand, pasteurisation removes this inherent risk by heating milk enough to kill disease‑causing bacteria while preserving its nutritional quality. This doesn’t mean pasteurised milk is risk free, as contamination can occur after pasteurisation during processing, packaging or handling. However, since mass pasteurisation was introduced, the number of foodborne illnesses attributed to dairy has decreased significantly (source, source). A few points are worth highlighting:

- When outbreaks are broken down by pasteurisation status, unpasteurised dairy products account for the vast majority of dairy‑associated illnesses and severe outcomes, despite much lower consumption than pasteurised dairy (source, source).

- Per serving, unpasteurised dairy (milk and cheese) are estimated to cause 840 times more illnesses and 45 times more hospitalisations than pasteurised products in the United States (source).

Because raw milk is associated with serious, sometimes life‑threatening infections, is consumed by a smaller group of people, and because a safer alternative exists, its profile is vastly different from other food products that have been linked to foodborne illnesses outbreaks.

Despite these issues, some people choose raw milk over pasteurised milk because of its supposedly added nutritional benefits. Claims range from reduced risk of allergies, asthma, or curing lactose intolerance. You can read more about how these hold up against evidence in our related fact-check here. This article breaks down the most common assumptions about raw milk’s benefits, checking them against the balance of evidence available on each topic.

In terms of basic nutrition:

- Pasteurisation is designed to kill pathogens while preserving nutritional quality. Protein, fat, lactose, minerals and most vitamins remain essentially intact; pasteurised milk is still a nutrient‑dense food rich in high‑quality protein and calcium (source).

- Some heat‑sensitive components (certain enzymes and small amounts of some vitamins) can be reduced, but this has not translated into clear differences in growth, general health or disease risk in well‑nourished populations. For example, Vitamin C is the only vitamin in milk that is noticeably reduced by heat, but milk is not a meaningful source of vitamin C to begin with, which is why it doesn’t reduce the nutritional value of pasteurised milk (source).

Bottom line: transparency needs to extend to social media content too

Transparency therefore has to extend not only to farm and kitchen practices but also to healthcare communication and social media content. When social media posts emphasise that “all foods carry risks” while omitting the differences in risk magnitude and severity between foods, and between population groups, they undermine rather than enhance informed choice.

If public‑health messaging treated every possible risk equally, eating would become unmanageably stressful and anxiety‑provoking. One way to think about it is that guidance operates from the top down, that is looking at the entirety of issues to guide recommendations to specific groups (from groups of people to those working in the food industry): it asks, “where do infections and serious complications actually occur?” and then focuses communication and restrictions on those foods, while aiming to enhance safer practices. By contrast, social media narratives often go bottom up: “I haven’t personally had a problem, my friends are fine, therefore the risk must be overblown,” which cannot capture population‑level patterns.

One good illustration is the Stanford trial led by Christopher Gardner, which tested one popular anecdote directly: that raw milk can “cure” lactose intolerance. In a randomised, double‑blind crossover study, adults with objectively confirmed lactose malabsorption drank raw milk, pasteurised milk and soy milk in separate periods. The trial found no improvement in lactose digestion or symptoms with raw milk compared with pasteurised milk; in some measurements, lactose malabsorption was actually higher at first with raw milk.

Gardner has been clear that this does not mean raw milk is not nourishing; it means that this specific claimed benefit is not supported by controlled evidence. The study is small, but it is a good illustration of how those ‘bottom up narratives’ (“it worked for me, so it shows raw milk can cure lactose intolerance”) might conflict with scientific evidence, because the idea behind this study was that this should be a straightforward hypothesis to test (source). Ultimately, this is why transparency about the limits of claims matters.

Here again, driving offers a useful analogy. All forms of transport carry some risk, but we reduce that risk with seat belts, speed limits and safe‑driving rules. Wearing a seat belt does not make driving risk‑free, just as pasteurisation does not make milk risk‑free. You can drive without ever having an accident; you can drink raw milk without ever getting sick. But when you look at crash statistics, people not wearing seat belts are much more likely to be badly hurt. Likewise, outbreak data show that people who drink raw milk are far more likely to be involved in serious dairy‑related infections than those who drink pasteurised milk (source).

So is raw milk unfairly singled out?

The idea that raw milk is unfairly singled out is a common concern on social media and among raw‑milk proponents. It is one of the main themes in Ann Bennett’s reel and is often echoed by prominent creators like Paul Saladino, who compare raw milk with other foods such as salads. Recently, Paul Saladino stated that eating salads containing raw spinach or lettuce was 274 times more dangerous than raw milk. So why do we hear the media talk more about raw milk?

Reality is more nuanced. This perceived emphasis on raw milk likely stems from two facts. First, official guidance for pregnant women and other vulnerable groups typically includes multiple food categories, such as certain soft cheeses, deli meats and pre‑prepared salads, as well as unpasteurised milk and products, so raw milk is not actually singled out instead of other risky foods in official recommendations.

Second, a recent survey showed that, despite clear public‑health guidance, many adults are not fully aware of the risks associated with raw‑milk consumption. This means public health messaging reinforcing the clear data on those risks, especially among children and pregnant women, is needed.

This emphasis is a risk‑management decision, not a moral judgment. Public‑health agencies highlight foods where modifying or avoiding consumption can prevent serious, preventable harm, particularly in vulnerable groups.

The ‘274 times more dangerous’ comparison is misleading

Paul Saladino’s claim that salads cause “274 times” more illness than raw milk is a good example of how data can be used in a way that sounds precise but actually lacks transparency.

Several points are crucial here. First, where did he get those numbers from? This matters because that is the first step towards transparency:

- He states that about 2.3 million people get sick every year from leafy greens and attributes this to CDC data, which broadly matches CDC‑based estimates that around 2.2 million US foodborne illnesses per year are attributable to leafy vegetables (source).

- He does not seem to explain, however, how he arrived at the “274” ratio or what annual raw‑milk illness figure he used.

- The comparison does not acknowledge that many more people eat leafy greens than drink raw milk.

Most importantly, if we just focus on the same CDC dataset, we see that some significant findings are left out. Indeed the study he draws the leafy‑greens number from also found that:

- Dairy as a commodity class accounts for the largest share of foodborne‑illness hospitalisations and a high share of deaths (source).

- Later breakdowns by pasteurisation status show that considering exposure, unpasteurised dairy products are responsible for a very high proportion of outbreak illnesses.

In other words, if one uses this dataset to argue that salads are more dangerous, one also has to acknowledge that dairy illnesses are more likely to be severe. That nuance is completely absent from the “salads are more dangerous than raw milk” narrative. It is a clear example of cherry‑picking: relying on one single figure (total leafy‑greens illnesses) while omitting exposure and severity to lead to a distorted picture of actual risk.

Final take away: what informed choice requires

People are, and should remain, free to choose what foods to eat. But for choices to be truly informed, they need a realistic picture of:

- Benefits: for example, ‘What are the benefits from eating leafy greens?’, ‘What are the real, evidence‑based differences (if any) between raw and pasteurised milk for most people?’;

- Risks: how many illnesses, hospitalisations and deaths occur per serving for each food, how do these risks differ for children, pregnant women and other vulnerable groups, and how can they be mitigated?

This is why health agencies continue to classify raw milk as a high‑risk food and strongly recommend that children, pregnant women, older adults and immunocompromised people do not drink it, even while acknowledging that all foods carry some level of risk.

We have contacted Ann Bennett and Paul Saladino and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources

- Geisel, H. (August 2025). “Mother sues Florida dairy farm, claiming she lost unborn baby after toddler got sick from drinking raw milk.”

- NHS (2023). “Foods to avoid in pregnancy.”

- NHS Inform (2025). “Escherichia coli (E. coli) O157.”

- U.S.F.D.A. “The Dangers of Raw Milk: Unpasteurized Milk Can Pose a Serious Health Risk.”

- Food Standards Agency (2025). “The Risk Analysis Process.”

- Christidis, T. et al. (2016). “Campylobacter spp. Prevalence and Levels in Raw Milk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.”

- Sebastianski, M.,et al.(2022). “Disease outbreaks linked to pasteurized and unpasteurized dairy products in Canada and the United States: a systematic review.”

- Koski, L., et al. (2022). “Foodborne illness outbreaks linked to unpasteurised milk and relationship to changes in state laws - United States, 1998-2018.”

- Costard, S., et al. (2017). “Outbreak-Related Disease Burden Associated with Consumption of Unpasteurized Cow’s Milk and Cheese, United States, 2009–2014. “

- Macdonald, L. E., et al. (2011). “A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of pasteurization on milk vitamins, and evidence for raw milk consumption and other health-related outcomes.”

- Renner, E. (1989). “Micronutrients in milk and milk-based food products.”

- Mummah, S. et al. (2014). “Effect of Raw Milk on Lactose Intolerance: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study.”

- Ipaktchian, S. (2014). “Claim that raw milk reduces lactose intolerance doesn't pass smell test, study finds.”

- CDC (2025). “Safer Food Choices for Pregnant Women.”

- Soucheray, S. (2025). “U Penn survey shows only 56% of Americans understand drinking raw milk is risky.”

- Painter, J. A., et al. (2013). “Attribution of Foodborne Illnesses, Hospitalizations, and Deaths to Food Commodities by using Outbreak Data, United States, 1998–2008.”

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)