Why the Dave Asprey "Meat Pyramid” presents a misleading picture

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

A recent social media post by Dave Asprey, founder of “Bulletproof” (an American brand that sells, amongst others, coffee, high protein bars and supplements) showcases his version of a food pyramid, in light of the recent guidelines published by the United States government.

The pyramid shared by Asprey only showcases meat, with some smaller references to coffee and butter. In the post, Asprey mentions: “I have plenty of variety in my diet. These are all different cuts of meat (and to be super clear, I am not carnivore. I eat low toxin vegetables, white rice, and low toxin fruit. And tons of herbs which have way more polyphenols than vegetables.)”

Despite these clarifications, the visual framing of the pyramid suggests that a dietary pattern high in red meat can form the foundation of a healthy diet.

This raises several questions:

- What do food pyramids represent, and why do they exist?

- Is there scientific support for food pyramids that promote diets high in red meat?

- Is the claim that herbs contain more polyphenols than vegetables accurate?

Let’s check what the existing scientific evidence says.

Food pyramids and similar dietary guides are public-health tools designed to translate nutrition science into clear, population-level guidance. Across countries, these visuals consistently emphasise water, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and plant foods as dietary foundations, while recommending moderation in red meat consumption. Scientific evidence links high and long-term red meat intake to increased health risks and environmental impacts, making meat-heavy food pyramids an inaccurate representation of evidence-based healthy eating.

When popular influencers post what they consider to be a healthy eating pattern, they are not only sharing an opinion; they are ‘educating’ and shaping followers’ views. Unfortunately, many people do not check whether claims are backed by evidence, and often interpret visibility as credibility.

Food pyramids and similar visuals are public-health tools, designed to communicate evidence-based dietary guidance at a population level. When these formats are used to promote highly selective or extreme eating patterns, they can mislead consumers into believing that such approaches are broadly safe, effective, or supported by scientific consensus.

Visibility is not the same as credibility.: High visibility on social media does not equal scientific credibility. Nutrition advice should be weighed by evidence and qualifications, not follower count. Reliable claims should be backed by scientific studies or data.

Why do we have food pyramids and what do they represent?

Official food pyramids around the world

Across countries, official food pyramids and dietary-guideline visuals are remarkably consistent in their core message. In much of Europe, traditional food pyramids place water and unsweetened beverages at the base, followed by plentiful fruits and vegetables, then grains, potatoes and pulses, with dairy and animal/plant protein sources above, oils and nuts in smaller amounts, and sweets, snacks and sugary drinks at the top, signalling that plant-based foods should be eaten most and energy-dense, low-nutrient foods least (source).

The Swiss food pyramid is an example: it starts with drinks, then fruit and vegetables, cereals and potatoes, protein sources and dairy, small amounts of oils and nuts, and finally sweets, emphasising variety and moderation.

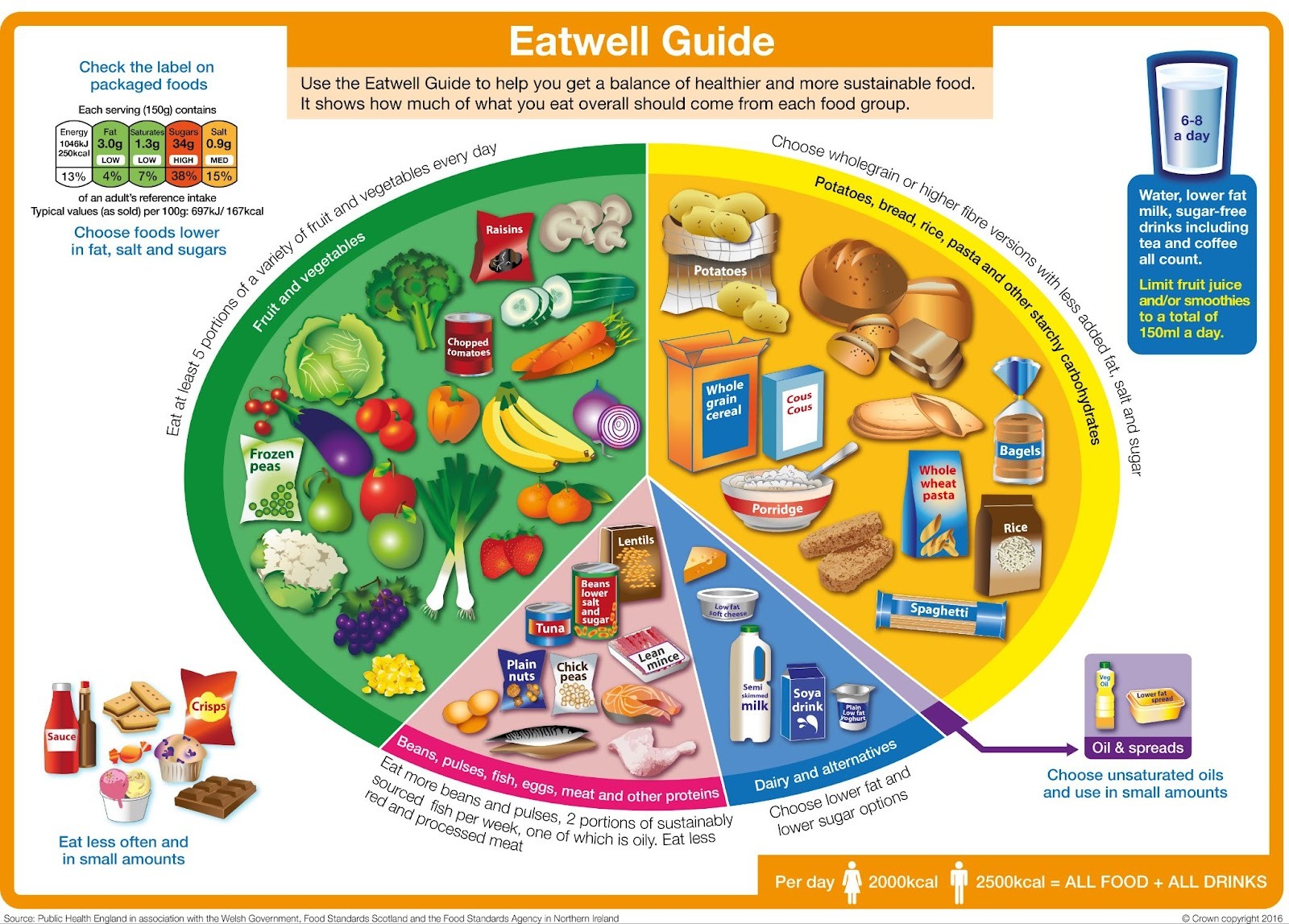

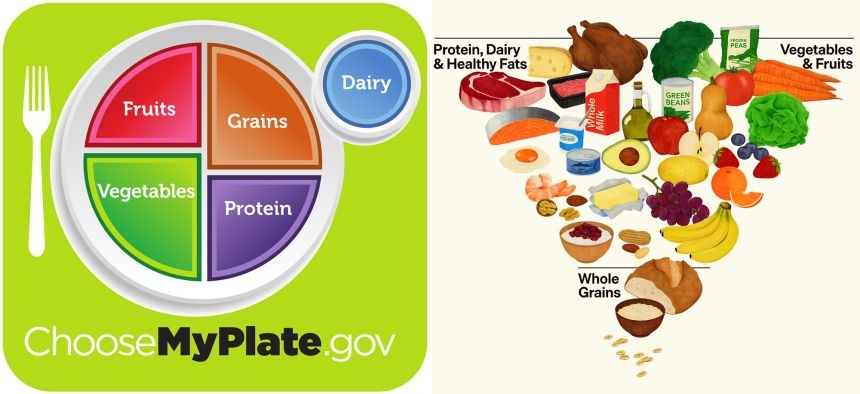

Other European guides differ in format but not in principle: The UK’s Eatwell Guide uses a plate rather than a pyramid, but conveys similar proportions: around half the plate is fruit and vegetables, with whole grains as a major component, smaller sections for protein foods and dairy (or alternatives), and oils and spreads limited, alongside advice to reduce red and processed meat, salt and sugar.

In the United States, the long-standing MyPlate model also highlights proportion — half the plate fruits and vegetables, the rest grains and protein, with dairy on the side — but the new 2025–2030 U.S. Dietary Guidelines have reintroduced a food-pyramid-style graphic that stands out visually, as animal protein foods and fats appear more prominently than in plant‑centric designs used elsewhere.

What is the relevance of having a food pyramid?

The relevance of a food pyramid (or plate, wheel, etc.) is not to tell people exactly what to eat, but to serve a public-health and educational function, such as informing school meal programmes, public food procurement, and public-health policies, and supporting clinicians and health professionals by providing a shared reference for what a healthy eating pattern looks like.

Because they are visual and easy to understand, food pyramids can also help the general public orient themselves toward healthy eating, offering guidance on proportions, balance, and variety rather than rigid rules.

Is the food pyramid or “plate” a “one-size-fits-all”?

No, and it is not meant to be. They are used to guide the population on what evidence points to be a healthy eating pattern, showing proportions of food groups, encouraging variety, moderation and supporting long-term health for most people. Specific eating patterns, however, should be adapted to age, sex, health status, culture and preference.

Claim 1 (suggested by the red meat pyramid visual): High consumption of red meat can be a good foundation for healthy diets

Fact-check: The message conveyed by this visual is inconsistent with evidence on the health impacts of high red meat consumption.

In his post, Asprey clarifies that he is “not carnivore” and that he also eats “low-toxin vegetables, white rice, and low-toxin fruit.” This suggests that he does not exclusively follow an animal-based eating pattern, but rather includes plant foods and grains. However, regardless of these clarifications, the visual message of his “food pyramid” signals that there is space for a healthy eating pattern characterised by a high intake of red meat.

This is where scientific evidence becomes relevant. A substantial body of research has consistently shown that high consumption of red meat, particularly when frequently and long-term, is associated with an increased risk of several chronic diseases, including certain cancers and type 2 diabetes (source, source). In addition, when viewed through the lens of sustainable diets, red meat production is one of the largest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, making it a significant driver of climate change (source).

Claim 2: Herbs have more polyphenols than vegetables

Fact-check: Though it is true that herbs can be very dense in polyphenols per gram, the actual quantity of herbs typically consumed is much smaller than that of other polyphenol-rich foods.

Polyphenols are a large family of plant compounds found in several foods, such as grains, cereals, pulses, vegetables, spices, herbs, fruits, coffee and tea. When consumed regularly as part of a varied diet, polypheneols can have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, which are associated with lower risk of cancer, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disease, amongst others (source).

Eating “tons of herbs” can contribute to increasing polyphenols in the diet, but without a consistent, generous intake of fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds, overall exposure to polyphenols will likely be low.

Note on “low toxin” vegetables and fruit

In his post, Asprey mentions that he eats “low toxin” vegetables and fruits. Advice to avoid certain fruits and vegetables because they are high in toxins is not supported by evidence. Vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and legumes are consistently associated with better health outcomes, not with harm, when eaten as part of balanced diets. Read more in our Fact Check Plants are good for you, so why do wellness influencers call them toxic?.

Bottom Line

Food pyramids are not personal diet preferences — they are public-health tools meant to reflect the best available scientific evidence for the population at large. While individual eating patterns can vary, presenting a pyramid that visually centres red meat as the foundation of a healthy diet is misleading. Current evidence consistently supports dietary patterns rich in plant foods, with red meat consumed in moderation, both for long-term health and environmental sustainability.

We have contacted Dave Asprey and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources

European Commission (2025). “Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Knowledge Gateway”

Farvid, M.S., et. al. (2021). “Consumption of red meat and processed meat and cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies”

Chunxiao, L, et. al. (2024). “Meat consumption and incident type 2 diabetes: an individual-participant federated meta-analysis of 1·97 million adults with 100 000 incident cases from 31 cohorts in 20 countries”

González, N, et.al. (2020). “Meat consumption: Which are the current global risks? A review of recent (2010–2020) evidences”

Rudrapal, M, et.al. (2022). “Dietary Polyphenols and Their Role in Oxidative Stress-Induced Human Diseases: Insights Into Protective Effects, Antioxidant Potentials and Mechanism(s) of Action”

Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office FSVO (last modification in 2025). “Swiss Dietary Recommendations”

Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (last modification in 2024). “The Eatwell Guide”

United States Government (2026). “Eat Real Food”

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)