The real war that the new American dietary guidelines have created

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

New Dietary Guidelines have just been published in the United States, and they’ve sparked exactly what you would expect after months of polarising language: headlines, hot takes, and strong reactions from experts in nutrition and public health. We have compiled eleven reactions by nutrition experts to the guidelines. Here we ask a different question: what is the effect of these guidelines on the people they are supposed to help? At foodfacts.org, the main concern and focus is the consumer, and providing evidence that supports informed choices. For many consumers, the main impact so far has been confusion – which is precisely what guidelines are meant to avoid.

That confusion is also hard to address without accidentally feeding it. When politics and ideology are tightly woven into the rollout of public-health advice, even careful attempts to correct the record can reinforce the sense that nutrition is just another battleground between camps, rather than a field with a shared evidence base. The question that ends up lodged in people’s minds – “Who is right?” – is not where good public health communication should leave them.

Guidelines are meant to offer clarity, not stir confusion

The basic purpose of dietary guidelines is straightforward: translate the latest nutrition science into clear, practical advice that answers everyday questions such as “What should my plate look like?” and “What should we eat more or less of to support overall health?”. Every five years, an independent Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) reviews the available evidence - a process that takes about two years - and produces a report; HHS and USDA then use that report to create guidance for the whole population, which is used to shape school meals, food programmes and public campaigns. This year, political leaders announced a ‘historic reset,’ moving away from the traditional DGAC process and commissioning a separate review that was then used to justify guidelines diverging in some places from the committee’s conclusions.

While the DGAC’s report remains available, official guidelines are crucial to shape understanding. Tools like “5‑a‑day” and MyPlate exist precisely to reduce confusion: MyPlate shows, in one image, that a balanced meal means about half the plate should contain fruits and vegetables, plus some grains (preferably whole), some protein foods, and some dairy or fortified alternatives, all adaptable to culture, budget and preferences. “5‑a‑day” condenses fruit‑and‑vegetable advice into a slogan that is easy to recall. When the rollout of new guidelines instead leaves people asking “Was everything I was told before wrong?” and “Who am I supposed to believe now?”, the guidelines are not really helping consumers make informed decisions – they risk adding to the noise and diverting attention from the changes that really need to happen.

Where is the real “war”?

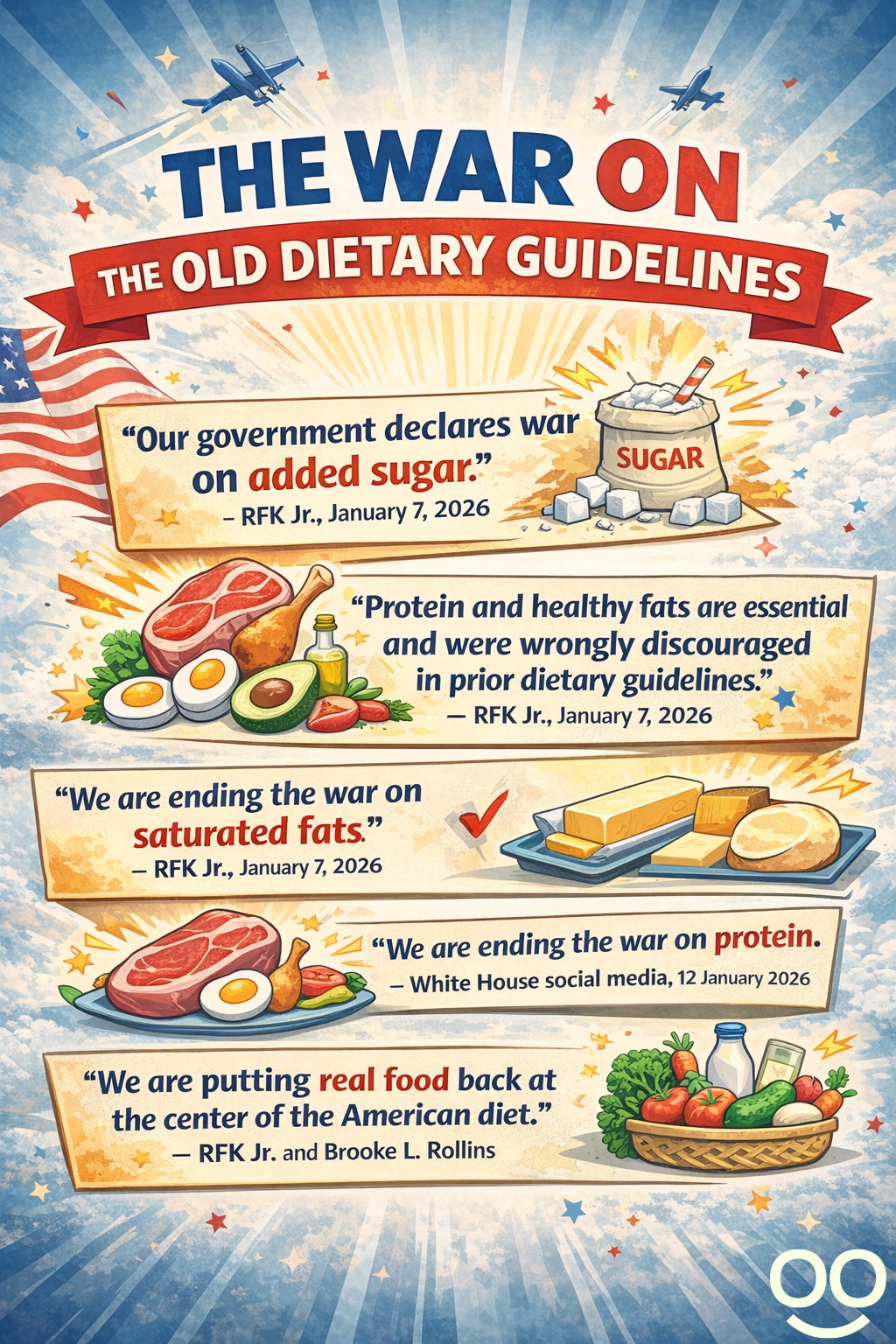

The language surrounding the new MAHA guidelines has been striking. Months before their release, MAHA supporters repeatedly attacked the “old food pyramid,” casting it as a carbohydrate‑heavy, industry‑skewed relic that needed to be overturned. They got the tone right: something needed to change. But the food pyramid in question already did: it was first updated in 2005 and then replaced in 2011 by MyPlate, in an effort to reflect the latest evidence from nutrition science and adapt to individuals’ varying needs and contexts. As a result, recent guidance has been built around MyPlate, not that old pyramid, for over a decade. So this choice of language was not only puzzling, it created noise and started to subtly undermine trust in the scientific process and experts that have updated those tools over time.

From the start, the MAHA communication strategy has been to present the new guidelines as a revolution. Their release was even described as “the most significant reset of federal nutrition policy in our nation’s history” (source).

Let’s start with positives: “eat real food” is an important and powerful message. But it’s presented as if it were a radical correction, implying that prior guidelines were to blame. Yet the previous Dietary Guidelines never promoted ultra‑processed foods as health-promoting; they have consistently recommended nutrient‑dense foods – vegetables, fruits, beans, whole grains, nuts, seeds, seafood, dairy and lean meats – and repeatedly told people to limit added sugar, saturated fat, sodium and refined grains. So the question is, how do we actually “put real food” back on Americans’ plates? Is it by changing guidelines that already emphasised “real food”, or by improving access to whole foods?

The rhetoric about “ending the war on saturated fats” is particularly loaded. One genuine shift from previous advice is that the new guidelines no longer recommend fat‑free options across the board and instead talk about the importance of “healthy fats.” So what are “healthy fats”? Researchers looking into clarifying that debate to update public health recommendations have put it like this:

“Based on the scientific evidence, consumers should focus on overall dietary patterns and consume healthful foods rich in healthy fats including nuts, vegetable oils, other plant sources of fats, and substitute these for unhealthful foods such as processed meats and foods high in sodium, added sugars, or refined carbohydrates. This may result in a total fat intake that exceeds 35% of calories, but the majority of the fats in such a dietary pattern would be healthy fats.”

In other words, healthy fats here seem to refer mostly to unsaturated fat. So it’s not just about reducing saturated fat, it’s about what we replace it with. But in public messaging, that nuance is overshadowed by the framing of saturated fat as a wrongful villain - “we are ending the war on saturated fats” – a framing that invites people to see earlier limits on saturated fat as ideological, even though the numerical recommendation (keeping saturated fat under 10% of calories) has not changed.

For anyone who follows MAHA supporters on social media, this will sound very familiar: it echoes narratives that describe evidence linking high LDL cholesterol and saturated fat to cardiovascular risk as “junk science” or corrupt, and therefore safe to ignore.

In visual rollouts of the new pyramid, a whole chicken and a large slab of red meat feature prominently, while the accompanying materials group butter and beef tallow alongside olive oil as “healthy fats.” Influencers such as Dave Asprey have amplified that emphasis with their own content, for example sharing a “Dave Asprey Pyramid” composed almost entirely of different cuts of red meat and joking that this is what “variety” looks like in his diet, with only a brief mention of selected “low‑toxin” vegetables, fruit and herbs.

In this context, for a listener or viewer, it is hard not to infer:

- If there was a “war” on saturated fat and we are now “ending” it, were earlier recommendations to limit (not demonise, but limit) red meat and animal fats simply wrong?

Yet in the text of the new guidelines, the numerical recommendation on saturated fat is unchanged: they still advise keeping saturated fat under 10% of daily calories, exactly as in past editions. Nothing fundamental about saturated fat has been overturned; what has changed is the political story being told about it. The risk is that people come away not with more context and understanding, but with the impression that “the science has flipped again” and maybe that experts can’t really be trusted.

To understand how this language lands with the public – the very people guidelines are meant to support – it helps to look closely at one concrete example.

A closer look: how one Fox News segment captures the confusion

The language around the guidelines started shifting long before the official release. This Fox News clip previewing the latest changes offers a brief interview that clearly illustrates how this framing can sow confusion. The segment ran under a headline about “new MAHA dietary guidelines prioritiz[ing] meat over plant-based proteins,” telling viewers the guidelines would “encourage people to eat more meat, full‑fat dairy [and] saturated fats” and “reject the emphasis on plant-based proteins.” The clear takeaway is:

More meat, less emphasis on plants.

But what is really striking is that while the on‑screen text and host framing stress less emphasis on plant-based proteins and more meat, the invited guest’s advice sounds a lot more familiar, not revolutionary. Celebrity fitness trainer Jillian Michaels talks about a diet “predominantly [of] whole foods,” emphasises fruits and vegetables, includes some whole grains, advocates a “protein‑centric” pattern, and advises using olive and avocado oil and nuts and seeds, with “some” saturated fat, reminding the public that this should be in moderation.

So on one side, the surface message appears to be: Meat over plants, war on saturated fat ended, plant emphasis scaled back - a polarising picture. On the other, the underlying advice highlights a much more balanced pattern where fruits and vegetables remain central, protein might come from both animal and plant sources, and unsaturated fats are encouraged over unlimited butter or beef tallow.

Interestingly, the host’s closing line is that his takeaway will be to tell his kids that they will be throwing some ribeyes on the grill, to which the guest adds that a side of vegetables would be good. For viewers, the contradictions are obvious: is the lesson that meat has been vindicated, or that the advice is essentially what they heard before? Is saturated fat “good” or “bad”?

In reality guidelines do not label foods as good or bad; they ask, in context, what proportions and patterns best support health given how people actually eat, including issues of access, food security and cultural differences.

Final thoughts

Evidence‑based dietary guidance and nutrition science are meant to rest on a clear process: start with questions, design studies to answer them, and then adjust recommendations as the weight of evidence accumulates – a system explicitly built to test its own assumptions and evolve when new data appears to change the picture. What might get eroded here is public understanding of that process, and with it trust, as political narratives about ending non-existing wars and revolutionising a system that had already been updated question the validity of well-established evidence, rather than explaining how it is being used.

In a “war,” one side wins and one side loses. In this narrative, animal protein appears to be cast on the winner’s side, trust in the scientific process might well decline, and amidst high confusion, consumers are left in the crossfire. Meanwhile, what gets lost is the real battle that would actually make America healthier: reshaping the food environment so that it becomes possible for most people to follow the recommended patterns. Until the focus shifts from symbolic fights to structural changes that align price, access and marketing with what the evidence already recommends, the dissonance between guidelines and everyday reality will persist – and so will the confusion around them. Because while an old pyramid has been flipped, the food environment remains unchanged.

While the language of revolution is loud, its practical effect is quiet: as attention is fixed on a flipped pyramid and a historical reset, the food industry itself is largely spared from having to change anything at all. Read more about how the modern food system is structured to prioritise corporate profit and make ultra‑processed and “junk” foods dominant — and why that matters for public health — in this article.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)