Are plant-based meat alternatives good for cholesterol? Cardiologists weigh in

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

A new look at plant-based meat and heart health

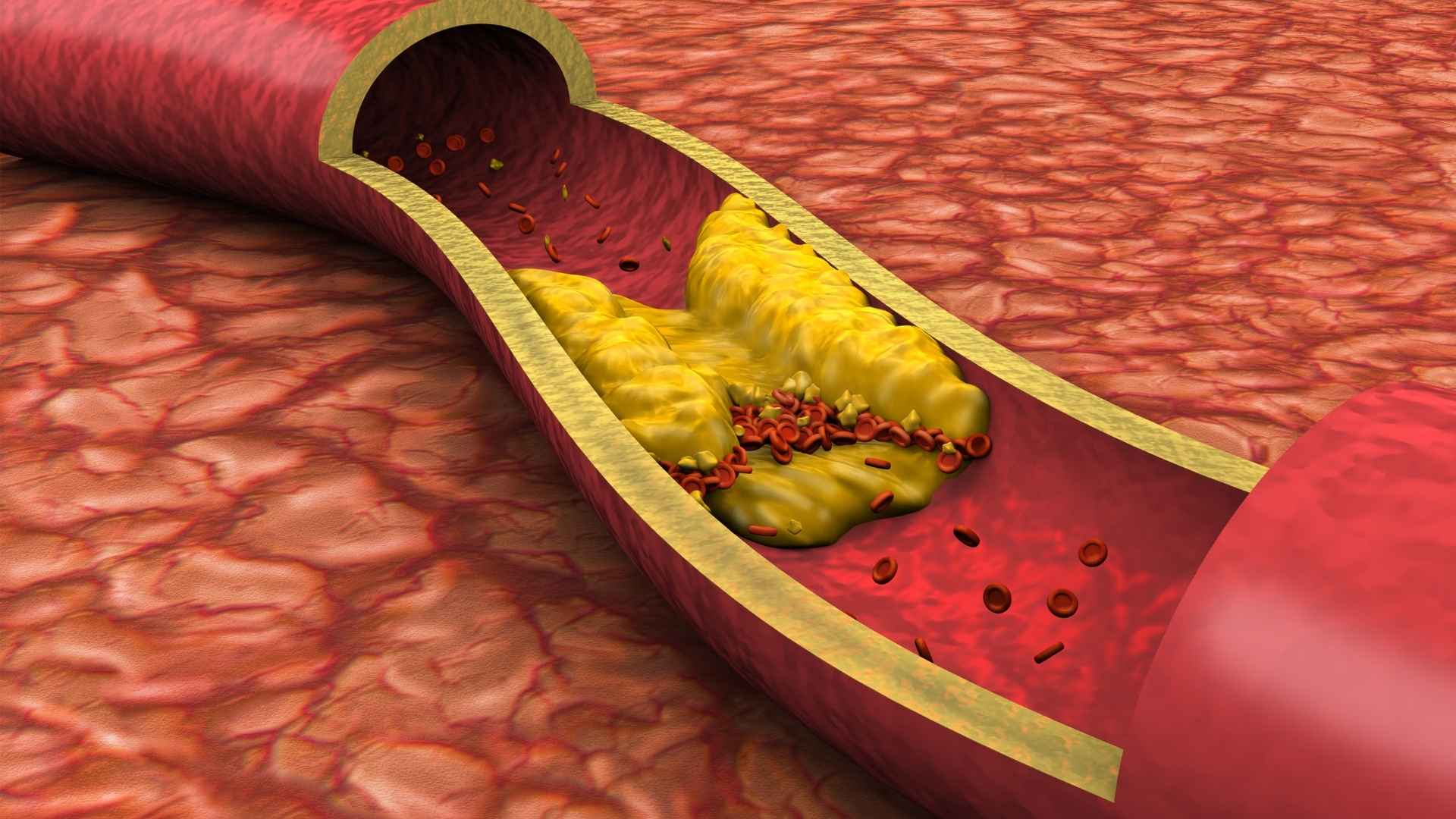

A major new systematic review and meta-analysis in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition suggests that replacing meat with plant-based meat alternatives (PBMAs) for a few weeks can modestly improve some markers of heart and metabolic health in adults without existing cardiovascular disease. Across seven randomized controlled trials including 369 adults, switching from meat to products like plant-based burgers, sausages, and mycoprotein-based foods lowered total cholesterol by about 6%, LDL "bad" cholesterol by about 12%, and body weight by around 1% over one to eight weeks. The research did not find meaningful changes in blood pressure, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, or fasting blood glucose in this short timeframe.

For anyone confused by headlines about "ultra-processed" vegan products being either miracle foods or metabolic disasters, these findings add nuance rather than a simple yes-or-no verdict. PBMAs appear capable of improving some cardiovascular risk factors when they displace meat, but the benefits are modest, short-term, and depend heavily on what these products are made from and how the rest of the diet looks. foodfacts.org has already covered this nuance by arguing that ultra-processed foods are not simple villains and that plant-based meat and health need to be judged on overall dietary patterns, not processing alone.

What did the study actually test?

The new review pooled data from seven randomized controlled trials in the UK, US, and Singapore, mostly involving healthy adults, with a few trials in people with overweight, hypercholesterolaemia, or higher diabetes risk. Participants were asked to replace some or all of their usual meat intake with PBMAs such as branded plant-based burgers, sausages, mince, and mycoprotein products like Quorn, generally for between four and eight weeks.

In most trials, the control group continued eating meat—often red and processed meat, sometimes including poultry and fish—while keeping the rest of their diet broadly the same. Because these are "swap" studies, the key question is not "are PBMAs perfect foods?" but "what happens when you replace meat with them, everything else being similar?" That distinction matters in a world where many people are unwilling or unable to jump straight from a meat-heavy diet to mostly whole plant foods.

The main cardiometabolic findings

When the seven trials were analysed together, three main effects emerged:

- LDL cholesterol fell by around 0.25 mmol/L, equivalent to roughly a 12% reduction from baseline.

- Total cholesterol dropped by about 0.29 mmol/L, around a 6% decrease.

- Body weight decreased by about 0.72 kg on average, roughly 1% of body weight, which the authors note is not clinically significant weight loss on its own.

No statistically significant differences were seen for HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, blood pressure, or fasting blood glucose. In additional “what‑if” checks called sensitivity analyses, where the data were re‑examined in slightly different ways to see if the results still held, a focus on mycoprotein-based products showed slightly larger cholesterol reductions, suggesting that fungi-based alternatives with more fibre and less saturated fat may be especially helpful for lipid profiles.

From a cardiovascular risk perspective, the cholesterol changes are small but real. A reduction in LDL is associated, in other contexts, with a meaningful reduction in long-term heart disease risk, especially when combined with other healthy behaviours.

Important limitations and conflicts of interest

The authors of the AJCN study are clear about the limits of the evidence. There were only seven randomized trials, most with small sample sizes and short durations of one to eight weeks. Several outcomes such as inflammatory markers, insulin, and detailed microbiome changes were either not measured often enough or not consistent enough to combine in meta-analyses.

Crucially, seven of the eight included publications were funded by PBMA manufacturers, including well-known brands. While industry funding does not automatically invalidate findings, it raises legitimate questions about study design, comparators, and reporting that independent replication will need to address. Risk-of-bias assessments judged only one trial as low risk in all domains, with others showing concerns or high risk, particularly around blinding and deviations from intended diets.

Why might plant-based meat alternatives help?

Nutritionally, many plant-based meat alternatives differ from meat in three important ways: they typically contain less saturated fat and no dietary cholesterol; more fibre and often more unsaturated fats; and a different matrix of plant proteins, starches, and additives. Replacing saturated fat and cholesterol with unsaturated fats and carbohydrates is known to lower LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol, and higher fibre intakes are also linked to better lipid profiles.

However, PBMAs are far from uniform. Some products are relatively nutrient-dense, with modest saturated fat and sodium, decent fibre, and added micronutrients. Others are closer to classic ultra-processed convenience foods: higher in salt, saturated fat, and energy density, with long ingredient lists and limited fibre. As foodfacts.org has explored in its deep dive on ultra-processed foods and plant-based meat, processing level alone does not determine health impact; what matters is the combination of ingredients, the foods they replace, and the broader diet.

"Carefully planned plant-based diets can support healthy living at every age. As with any eating pattern, plant-based diets should be thoughtfully planned to meet nutritional needs. If you’re interested in incorporating more plant-based options, try including a wide variety of plant foods, adding some meatless days to your meal plans, and using occasional plant-based meat alternatives to support a balanced diet. Whole foods such as tofu, tempeh, lentils, and beans are excellent nutrient-dense choices, while more processed plant-based meat alternatives can be useful meat replacements but labels matter, be mindful of plant based meat alternatives which are high in sodium and saturated fat." - Aenya Greene - foodfacts Dietician

The ultra-processed elephant in the room

By NOVA criteria, most of the PBMAs in the included trials are classed as ultra-processed foods, because they are formulated largely from protein isolates, refined fats, and industrial ingredients, with multiple additives used to mimic the sensory qualities of meat. The same AJCN paper notes that around 73% of PBMAs in one analysis were ultra-processed, compared with 92% of the meat products they replaced.

foodfacts.org has repeatedly warned against assuming all ultra-processed foods are equally harmful or equally benign. Ultra-processed plant-based burgers that displace high intakes of processed red meat may still be a net win for heart health and planetary health, even if they are not as beneficial as swapping meat for lentils, beans, nuts, or minimally processed tofu. The new meta-analysis supports that middle-ground view: PBMAs may be a useful stepping stone away from meat, not a magic bullet and not automatically a nutritional trap.

Practical takeaways for everyday eaters

For people who currently eat meat most days and are considering more plant-based options for health or environmental reasons, this research offers three grounded messages:

- Plant-based meat offers a simple swap that is low in saturated fat (while processed meat is generally high) and offers a source of fibre (while conventional meat has none), while offering similar levels of protein.

- PBMAs should be a bridge, not the final destination. Diets built around whole or minimally processed plant foods (beans, lentils, whole grains, nuts, seeds, vegetables, fruits) still show stronger links with lower cardiovascular risk than those centred on ultra-processed alternatives.

- Labels matter. Choosing plant-based products with reasonable sodium, modest saturated fat, some fibre, and clear protein sources is more important than simply choosing the item with the greenest branding or loudest health claims.

foodfacts.org's coverage of why some consumers are moving away from plant-based meat and how ultra-processed foods are framed in the media can help readers weigh health, taste, price, and values without falling into all-or-nothing thinking.

What to watch next

Looking ahead, the real test for plant-based meat alternatives will be longer, independently funded trials that track not only cholesterol and weight, but also blood pressure, glycaemic control, inflammatory markers, and eventually cardiovascular events. Studies comparing PBMAs directly with whole-food plant proteins (like pulses or nuts) rather than just with meat will also be crucial for understanding where these products sit in a truly heart-healthy diet.

For now, the evidence suggests that carefully chosen plant-based meat alternatives can play a constructive role in transitioning away from high meat intakes, particularly red and processed meat, as long as they are part of a broader shift towards plant-rich, fibre-rich, minimally processed eating. That aligns with foodfacts.org's wider mission to help people move beyond binary "good vs bad" labels and towards realistic, evidence-based food choices in a system that often pushes the opposite.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources + Further Reading

- American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (17 February 2025). Plant-based meat alternatives and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

- British Heart Foundation (23 March 2025). Ultra-processed foods: how bad are they for your health?

- Food Foundation (August 2024). Rethinking plant-based meat alternatives.

- foodfacts.org (5 December 2025). Why more meat-eaters are quietly choosing the vegan sausage roll at Greggs.

- foodfacts.org (22 October 2025). Ultra-processed foods: unpacking the myths and the real threats to health.

- foodfacts.org (23 October 2024). Fact-checking the firefighter analogy for cholesterol and heart disease

- foodfacts.org (18 November 2025). Ultra-processed foods, plant-based meat and your health.

- foodfacts.org (6 April 2025). Why consumers are moving away from plant-based meat.

- NIH / Public Health Nutrition (11 February 2019). Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them.

- PubMed (18 February 2025). Plant-based meat alternatives and cardiometabolic health.

- Silverman MG, Ference BA, Im K, et al. Association Between Lowering LDL-C and Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Among Different Therapeutic Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1289–1297. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.13985

- Universidad de Granada (20 March 2025). Replacing meat consumption with plant-based alternatives reduces total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol and body weight.

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)