Cancer cells do not “grow on plants”: what science really says about diet, meat and cancer

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

Host of podcast Pints with Aquinas Matt Fradd recently interviewed Tammy Peterson, wife of Jordan Peterson, and shared an extract of their conversation on social media. In the clip, Tammy shares a personal story about surviving a rare cancer diagnosis. During the conversation, she suggests that cancer cells “do not grow on fat; they grow on plants,” and therefore claims that “if anybody has had cancer, it’s best to stay away from plants.” Let’s take a closer look at the evidence behind this claim and what it might mean for people affected by cancer.

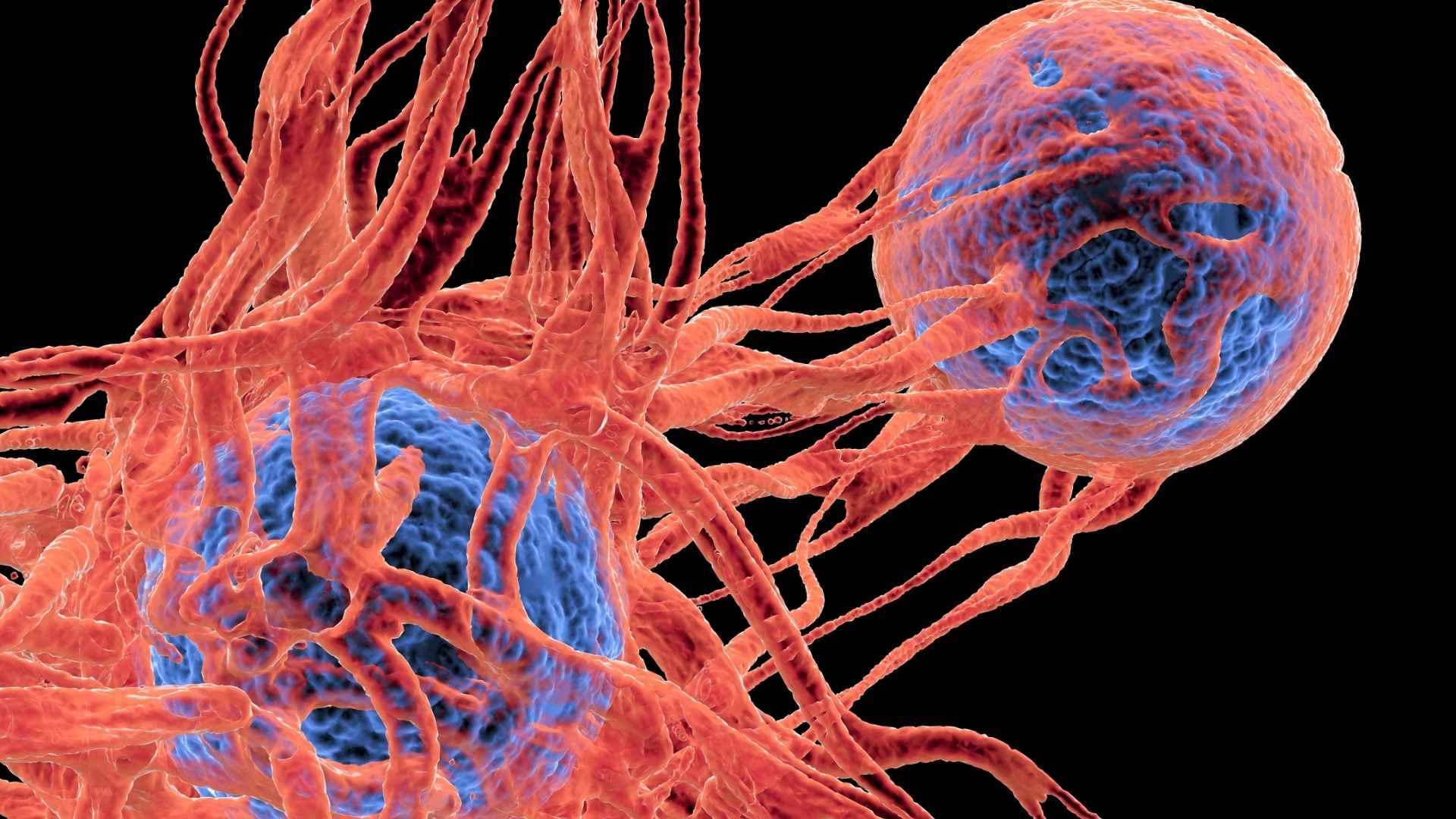

Cancer starts when mutations allow a cell to grow and divide uncontrollably, and tumors expand by recruiting blood vessels (angiogenesis) to supply glucose, amino acids and fatty acids from the bloodstream—regardless of whether those nutrients came from plant or animal foods. Current evidence on ketogenic and carnivore‑style diets in cancer patients is limited and mixed, while large reviews support limiting red and processed meat and emphasise fibre‑rich plant foods for cancer prevention.

Nutrition advice around cancer is emotionally charged and vulnerable people may radically change diets based on an anecdote that sounds “science‑y” but lacks any supporting data. Oversimplified messages like “plants feed cancer” or “meat doesn’t” can lead patients to abandon evidence‑based dietary patterns, ignore professional guidance, become skeptical of large, carefully conducted studies, and over‑trust single stories or influencers.

Personal stories of recovery can be powerful, but anecdotal experiences don’t prove cause and effect. Always check viral nutrition claims against evidence from multiple peer‑reviewed studies and guidance from major cancer organisations before making dietary changes.

Claim 1: “Cancer cells grow on plants, not fat.”

Fact-check: This claim implies that plant foods are the main or exclusive fuel for cancer cells, and that fats (and by extension meat) do not support tumor growth. In reality, cancer cells are metabolically flexible: they primarily use glucose but can also use amino acids (from protein) and fatty acids (from fat) regardless of whether those nutrients came from plants or animal products (source).

The phrasing also blurs the difference between “plant foods” and “carbohydrates.” Whole plant foods (like vegetables, fruits, and pulses) are rich in carbohydrate, but so are refined sugars and starches, which are a very different category nutritionally; animal foods, which supply amino acids and fatty acids can also be used by cancer cells as fuel (source). By framing the issue as “plants versus fat” rather than total energy balance, body weight, metabolic health and food quality, the claim oversimplifies complex cancer biology and misleads people into thinking that vegetables, fruit and whole grains are inherently dangerous if they have cancer.

How do cancer cells actually grow?

Cancer starts when mutations and other changes allow a cell to ignore normal growth controls, divide uncontrollably and eventually form a mass of abnormal cells. As tumors grow, they recruit new blood vessels (angiogenesis) that deliver glucose, amino acids and fatty acids from the bloodstream; these fuels come from all macronutrients in the diet, not from “plants” in particular, which is why scientists do not describe cancer as “growing on plants” but as using energy and building blocks from the whole diet (source, source, source, source, source).

Does eating plants “feed” cancer or put patients at risk?

No clinical guideline recommends (source, source) that people with cancer avoid plant foods as a group; oncology nutrition guidance generally encourages a plant‑forward eating pattern unless there are specific medical reasons to restrict fibre temporarily (for example, certain bowel complications). Observational studies (source, source) in cancer survivors show that dietary patterns rich in fruit, vegetables, whole grains and legumes are often associated with better overall survival and lower recurrence risk.

Cancer cells do need glucose, but the body can make glucose from many sources—carbohydrates, some amino acids and even glycerol from fats—so cutting out vegetables does not “starve” tumours of glucose while sparing the rest of the body. At the same time, plant foods provide vitamins, minerals, fibre and phytochemicals that support immune function and gut health which can be compromised on a very restrictive, meat‑only diet.

Evidence on plant-based diets and cancer prevention

Large cohort studies (source, source) and international reviews consistently (source, source) find that plant‑rich dietary patterns—high in vegetables, fruit, whole grains, legumes and nuts—are linked to lower risk of several cancers, particularly colorectal cancer. The 5th edition of the European Code Against Cancer advises people to “eat a healthy diet” by prioritising whole grains and other fibre‑rich foods and by limiting red meat and avoiding processed meat to reduce cancer risk.

Fibre, the colon, and the immune system

Dietary fibre is almost absent from meat, eggs and dairy but abundant in whole plant foods such as whole grains, legumes, vegetables, fruit, nuts and seeds. In the colon, fibre is fermented by gut microbes into short‑chain fatty acids like butyrate, acetate and propionate, which help maintain the intestinal barrier, dampen inflammation and may inhibit tumour development (source). Epidemiological analyses report that higher intakes of dietary fibre and whole grains are associated with lower colorectal cancer incidence, while low fibre intake and heavy reliance on refined grains and animal products without plant foods are linked to higher risk.

Fibre deficiency can disturb the microbiome, promote degradation of the protective mucus layer in the colon and increase susceptibility to inflammation, which may raise colorectal cancer risk over time (source). Several prospective studies and meta‑analyses (source, source), including EPIC (source) and pooled cohorts, find that higher fibre intake is associated with reduced colorectal cancer risk, and the European Code Against Cancer explicitly cites foods containing dietary fibre as protective. A carnivore diet, by eliminating virtually all fibre, runs counter to this evidence and may adversely affect long‑term colon and immune health unless it is very carefully managed and medically supervised.

Claim 2 (implied by the anecdote): Following a carnivore diet can cure/prevent cancer

In the video posted by Matt Fradd Tammy Peterson suggests that following a carnivore diet helped her survive cancer.

Is there evidence that a carnivore diet helps during cancer treatment?

Current research focuses primarily on ketogenic diets (very low carbohydrate, high fat, moderate protein), not on strict carnivore diets that eliminate nearly all plant foods. A recent meta‑analysis of ketogenic diets in cancer patients found improvements in fat mass, visceral fat, insulin, blood glucose, inflammation markers and some quality‑of‑life scores, but it did not demonstrate clear survival benefits or prove that avoiding all plant foods is necessary.

Expert reviews describe ketogenic diets in cancer care as still experimental and debated, because human studies so far are small, mixed in their results and limited to specific tumor types, so they do not yet show a clear, consistent anti‑cancer benefit. These reviews also stress that such diets are very restrictive and must be carefully supervised to avoid malnutrition, since cutting out many carbohydrate‑rich foods can reduce intake of fibre, several B‑vitamins (such as thiamine and folate), vitamin A, vitamin E, calcium, magnesium, iron and potassium, all of which are important for maintaining weight, muscle mass, immune function and tolerance of treatment. Many ketogenic protocols used in trials still include non‑starchy vegetables, nuts and other plant foods, which directly contradicts the idea that people with cancer should completely “stay away from plants”, and there are currently no robust randomised controlled trials showing that an all‑meat, plant‑free carnivore diet improves cancer control or survival compared with balanced, guideline‑based diets.

Saturated fat, cholesterol and cancer risk

High intakes of saturated fat are strongly linked to cardiovascular disease and can contribute to obesity and insulin resistance, which themselves increase risk for several cancers, including post‑menopausal breast, colorectal and endometrial cancers (source). Diets centered on fatty meats and high‑fat dairy tend to be high in saturated fat and cholesterol and low in fibre, which can worsen lipid profiles and inflammation, particularly over years (source, source).

Meta‑analyses of ketogenic diets in cancer patients note changes in LDL and total cholesterol and emphasise careful monitoring, especially in populations already at high cardiovascular risk. In prevention guidelines, organisations stress maintaining a healthy body weight, limiting saturated fat and favoring unsaturated fats from plant oils, nuts, seeds and fish rather than relying heavily on animal fat.

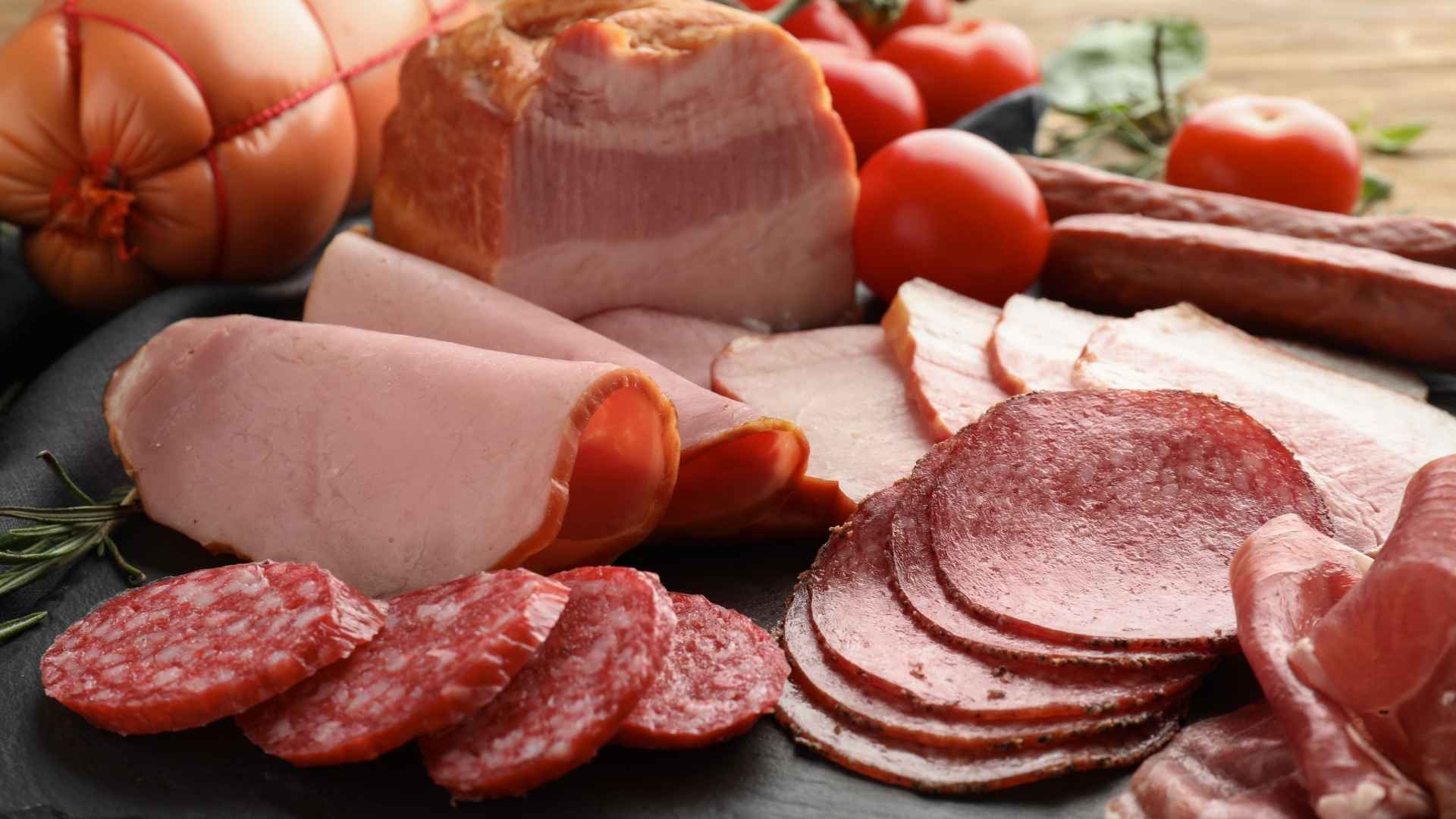

How strong is the evidence that red and processed meat increase cancer risk?

In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified processed meat (such as bacon, sausages, ham and some deli meats) as “Group 1 carcinogenic to humans” based on sufficient evidence that it causes colorectal cancer. Red meat (beef, pork, lamb, veal, mutton, horse, goat) was classified as “Group 2A probably carcinogenic to humans” based on limited evidence in humans and strong mechanistic evidence.

A 2011 meta‑analysis, updated by a more recent 2025 meta‑analysis, found that higher consumption of red and processed meat was associated with roughly 15–22% increased risk of colorectal cancer, reinforcing earlier findings that risk rises with greater intake. Other analyses (source, source) report that red meat is a risk factor for colon, colorectal and rectal cancer in Asian populations, and that replacing red and processed meat with fish can modestly reduce colorectal cancer risk. Public health bodies like the WHO and the American Institute for Cancer Research emphasise that “Group 1” classification reflects certainty that a cause–effect relationship exists, not that processed meat is as dangerous as tobacco on an absolute scale; risk rises with amount and frequency.

Are there flaws or limitations in meat–cancer studies?

Most meat and cancer data come from observational cohorts, which can be affected by residual confounding (for example, people who eat more processed meat may smoke more or exercise less) and measurement error in self‑reported diet. However, many studies adjust for smoking, alcohol, BMI and other lifestyle factors, and still detect a dose‑response relationship between processed meat and colorectal cancer, which strengthens the likelihood of a true association (source).

There is also mechanistic support: processing can introduce nitrites, N‑nitroso compounds, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heterocyclic amines, which can damage DNA in the gut, while high heme iron in red meat can promote oxidative stress and formation of carcinogenic compounds in the colon. Even with limitations, the convergence of epidemiology, mechanistic data and consistent findings across populations is strong enough that major bodies worldwide recommend limiting processed meat and moderating red meat.

The carnivore diet is extreme and highly restrictive with little scientific support for its health claims. It removes plant foods known to lower cancer risk while emphasising red and processed meats linked to increased risk. The diet is lacking in fibre, antioxidants, and phytonutrients, and can create nutritional deficiencies over time. Promoting these claims can be dangerous and add unnecessary stress for people going through cancer treatment.

What evidence exists for diet “starving” cancer, including fat-focused approaches?

Many viral posts claim to have found the diet that “starves cancer,” but research shows cancer is biologically complex and adapts to different fuels, so no single macronutrient (like fat or carbs) can simply be removed to switch cancer off. Current evidence suggests some targeted dietary strategies may modestly influence metabolism or the immune response in specific settings, but they are not proven cures and need more rigorous human trials.

How claims like this fuel confusion and distrust

The Instagram clip uses absolute language (“cancer cells grow on plants… they don’t grow on fat”; “best to stay away from plants”) that clashes with the cautious, probability‑based way science communicates risk. It also presents a one‑sided, anecdote‑driven narrative without acknowledging the large body of evidence linking processed meat to cancer, supporting fibre‑rich plant foods, or the uncertainties and trade‑offs in ketogenic or carnivore approaches.

Such messaging can make rigorous research and expert guidelines appear confusing or “contradictory,” because they rarely offer simple yes/no answers and instead talk in terms of relative risk and patterns over time. When people see bold, confident statements on social media that directly contradict major cancer agencies but are not backed by trials or mechanistic explanations, it can deepen skepticism toward experts and encourage a “choose‑your‑own‑science” culture.

For people living with cancer, this can translate into real harm: abandoning plant‑rich diets they tolerate well, risking nutrient deficiencies, ignoring individualised advice from oncology dietitians and feeling guilty or fearful about eating foods—like vegetables and whole grains—that are generally associated with better long‑term health.

For more information, check out this article detailing popular cancer myths and questions circulating online.

We have contacted Matt Fradd and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources

- DeBerardinis, R.J. & Chandel, N.S. (2016). “Fundamentals of cancer metabolism.”

- Cooper, G.M. (2000). “The development and causes of cancer.”

- Canadian Cancer Society. (2025). “How cancer starts, grows and spreads.”

- Cancer Research UK. (2023). “Benign and malignant tumours and how cancers grow.”

- MSD Manuals Professional Edition (2024). “Cellular and molecular basis of cancer.”

- World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research (2018). “Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: A Global Perspective (Third Expert Report).”

- Cancer Research UK (2024). “What should I eat to prepare for cancer treatment?”

- Ratjen, I. (2024). “Post-diagnostic reliance on plant-compared with animal-based foods and all-cause mortality in omnivorous long-term colorectal cancer survivors.”

- Ying, Q. (2025). “Pre- and post-diagnosis dietary patterns and overall survival in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer: a prospective cohort study.”

- Leitzmann, M. F., et al. (2026). “European Code Against Cancer, 5th edition - diet, excess body weight, physical activity, sedentary behavior, breastfeeding, and cancer.”

- Kim, J. (2023). “Plant-based dietary patterns and the risk of digestive system cancers in 3 large prospective cohort studies.”

- Kim, J. (2022). “Plant-based dietary patterns defined by a priori indices and colorectal cancer risk by sex and race/ethnicity: the Multiethnic Cohort Study.”

- Xie, L. (2025). “Plant-based dietary patterns defined by a priori indices and colorectal cancer risk by sex and race/ethnicity: the Multiethnic Cohort Study.”

- Wang, Y. (2023). “Associations between plant-based dietary patterns and risks of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mortality – a systematic review and meta-analysis.”

- Ungvari, Z. (2025). “Association between red and processed meat consumption and colorectal cancer risk: a comprehensive meta-analysis of prospective studies.”

- Liu, G. (2024). “Short-chain fatty acids play a positive role in colorectal cancer.”

- Celiberto, F. (2023). “Fibres and Colorectal Cancer: Clinical and Molecular Evidence.”

- Chan, D.S.M. (2011). “Red and Processed Meat and Colorectal Cancer Incidence: Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies.”

- Bingham, S.A. (2003). “Dietary fibre in food and protection against colorectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): an observational study.”

- Aune, D. (2011). “Dietary fibre, whole grains, and risk of colorectal cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies.”

- Riboli, E., et al. (2002). “European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): study populations and data collection.”

- Zhang, M. (2025). “Impact of ketogenic diets on cancer patient outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis.”

- Da Prat, V. (2024). “Anticancer restrictive diets and the risk of psychological distress: Review and perspectives.”

- Crosby, L. (2021). “Ketogenic Diets and Chronic Disease: Weighing the Benefits Against the Risks.”

- Gallagher, E.J. (2015). ”Obesity and Diabetes: The Increased Risk of Cancer and Cancer-Related Mortality.”

- Vogtschmidt, Y.D. (2024). “Replacement of Saturated Fatty Acids from Meat by Dairy Sources in Relation to Incident Cardiovascular Disease: The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Norfolk Study.”

- Hull, S.C. (2025). “Diet and Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer: JACC: CardioOncology State-of-the-Art Review.”

- International Agency on Cancer Research, Press Release (2015). “IARC Monographs evaluate consumption of red meat and processed meat.”

- Liao, Z. (2025). “Associations between the consumption of red meat and processed meat and the incidence of colorectal cancer in Asia: a meta-analysis.”

- Salman, A. (2015). “Diet and Colorectal Cancer Risk in Asia - a Systematic Review.”

- Fan, H. (2023). “Trans-vaccenic acid reprograms CD8+ T cells and anti-tumour immunity.”

- Cancer Research UK. (2025). “Food and cancer myths: questions and answers.”

- Foodfacts.org (11 September 2025). Does unprocessed red meat cause cancer?

- Foodfacts.org (19 December 2024). Are seed oils fuelling colon cancer?

- Foodfacts.org (13 June 2025).The carnivore diet: what does the data say about its impact on female health?

- Foodfacts.org (2 October 2025). Can we reverse Type 2 Diabetes with an animal-based diet?

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)