No, Pork Isn’t a Superfood: How One Tiny Study Spawned Misleading ‘Live Longer’ Headlines

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

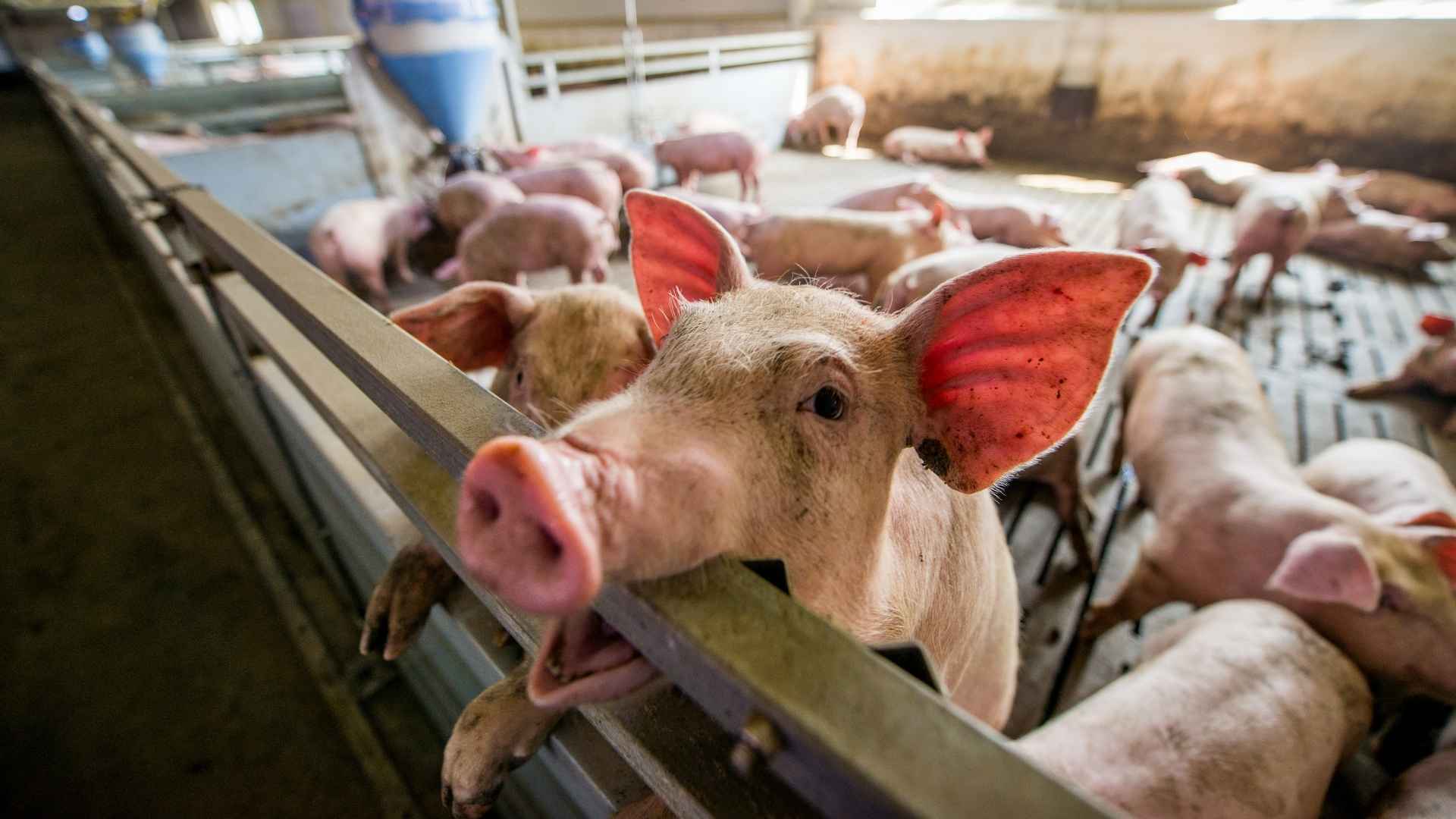

A Daily Mail article reports that adding lean pork to your diet could help you live longer, suggesting that minimally processed pork has the same health benefits as chickpeas, lentils and beans. It presents these statements as being backed by new research in older adults, using a plant‑forward eating pattern as the context for the findings. Let’s look at what the study actually showed, and whether it supports this conclusion.

The research shows that lean, minimally processed pork did not worsen certain blood markers when eaten as part of a carefully designed, plant‑forward diet in older adults over a few weeks. That is very different from showing that pork helps people live longer or that it offers the same long‑term health benefits as beans and pulses in everyday diets.

Most people will only ever see – or remember – the headline, not the fine print of the study. When a narrow ‘none of the markers studied got worse over a few weeks’ finding is turned into ‘this food is healthy, similar to beans,’ nutrition literacy gets eroded. It also strips away the context that actually matters for consumers: how pork is typically eaten (often as processed products), how much of it is recommended, how much pulses are recommended, and what the rest of the diet needs to look like to support long‑term health and longevity. Without those details, readers are left with a simple but misleading takeaway that doesn’t help them make informed choices about their everyday meals.

When you see a headline calling a food 'the healthiest,' look for context. Is that claim resting on a single study in a specific group, or on a larger body of evidence that’s built up over time, backed by consistent findings and plausible mechanisms? Headlines often skip this step – but asking it is one of the quickest ways to tell whether you’re looking at a genuine shift in understanding or just another attention‑grabbing spin.

Claim 1: “Adding lean pork to your diet could help you live longer, with minimally processed cuts boasting the same health benefits as chickpeas, lentils and beans, scientists say.”

Fact-check: It’s a catchy headline – but it isn’t what the science shows. The claim rests on a small, short-term nutrition study in older adults that simply cannot tell us whether pork helps people live longer or matches the health benefits of pulses. Stretching these findings into promises of longevity and “health benefits equivalent to beans” is pure spin.

What the study actually did

The trial followed 36 older adults who completed two eight‑week diet phases: one included lean pork, the other included pulses (lentils and chickpeas), both in so-called ‘plant‑forward’ meals containing fruit, veg and grains. Researchers measured blood markers, body composition and some functional outcomes. They did not track heart attacks, strokes, dementia, cancer or how long people lived.

After eight weeks on the lean pork diet, the study did not detect evidence of harm in the markers measured. That’s all. Not finding short‑term damage over two months is very different from saying that pork benefits long‑term health; ‘no harm’ is not the same as ‘health benefit’.

The pork was also unusually handled: lean cuts were trimmed of fat and cooked in a rotisserie oven using olive oil. That’s a world away from how pork is typically eaten in real life – think bacon, sausages, pies – high in salt and saturated fat.

Improvements were about the overall diet

.jpg)

Both the pork‑based and pulse‑based diets improved several markers compared with the participants’ usual eating patterns. The most plausible explanation – everyone was eating more fruit, vegetables and grains and fewer unhealthy foods than they normally did.

Crucially, the lack of a difference between the pork and pulse diets does not mean they are equally healthy. ‘No significant difference’ in science often just means a study was too small or too short to detect one. It does not magically prove that lean pork delivers the same long‑term health benefits as pulses.

Claim 2: “Moderate consumption of lean red meats such as pork may help support muscle-maintenance with ageing.”

The Daily Mail also adds that “total cholesterol levels also dropped after following the diet plans, reducing the risk of heart attack and stroke.” The implication here is therefore that eating pork (as part of a plant-forward) diet can convey multiple health benefits, from supporting muscle strength to lowering cholesterol.

Fact-check: The claims about muscle strength and cholesterol are oversold. Participants lost some weight on both diets while maintaining simple measures of strength such as grip strength and chair‑rise performance – they did not become stronger; they just didn’t get weaker.

On cholesterol, the pork diet was reported to raise HDL ‘good’ cholesterol. But experts increasingly caution that HDL changes are not a reliable guide to heart disease risk; large studies show that simply having higher HDL is not consistently protective (source). Meanwhile, total cholesterol fell in both diets, again suggesting the overall dietary pattern – not pork itself – was doing the heavy lifting.

Cognitive benefits and reassurance about cancer risk were also implied, despite the study not directly measuring cognitive performance or tracking cancer outcomes. That kind of leap in health claims is speculative at best.

A note on funding and framing

The study was funded by meat industry and farming groups and that influence shows. Instead of asking whether red meat benefits health or could be replaced, it tested whether eating pork causes short‑term harm – not causing harm does not equal healthy.

The research also overlooked environmental and animal welfare issues, which are now increasingly central to public health discussions.

What the evidence for beans and pulses looks like

By contrast, the case for beans and pulses being 'healthy'” rests on a wide base of evidence:

- Cardiovascular disease and diabetes

Systematic reviews and meta‑analyses indicate that the regular consumption of pulses is linked with modestly lower cardiovascular disease and coronary heart disease risk in observational data (source, source). Randomised trials and pooling of RCTs suggest that pulses, when they replace more refined or meat‑heavy options, can improve established risk factors such as LDL cholesterol and some markers of glycaemic control (source). - Mechanistic fit with plant‑based patterns

Pulses are high in fibre, contain low‑glycaemic carbohydrates, and provide plant protein along with minerals and bioactive compounds, while being low in saturated fat. They are also central to traditional dietary patterns (for example, Mediterranean‑style diets) that consistently associate with lower cardiometabolic and mortality risk (source).

Final takeaway: why this kind of coverage confuses more than it clarifies

Taken together, the way this article presents the study risks leaving readers with an entirely different message from what the science suggests: that “pork is healthy now,” on roughly the same footing as lentils, peas and beans. The headline, subheads and opening paragraphs all lean into a simple causal story – add lean pork, live longer, get the same benefits as pulses – even though the study only shows that, over eight weeks, lean pork did not look worse than pulses when slotted into a tightly controlled, plant‑forward diet with lots of support.

Pulses have been repeatedly promoted in recent years as foods most people should eat more of, for health, affordability and sustainability. When an article suggests pork now belongs in that same 'actively encouraged' category, it blurs the line between “may fit into a healthy pattern in moderation” and “this is something we should all be eating more of.”

In fact, a poll halfway down the article asks the question: Do YOU think pork is healthy? To which 79 per cent of respondents answered ‘yes.’ Reporting on the above study is then followed by references to Eric Berg, D.C., who the Daily Mail inaccurately refers to as a keto diet expert, praising the benefits of pork fat. Yet what the article ends with is a section on bowel cancer risks, WHO’s carcinogen classification of processed meat, and UK calls to limit bacon, sausages and ham – which are some of the most popular forms in which pork is typically consumed in the UK. Given the lack of context provided by the article to cover the findings of this recent study, this might well leave readers juggling two incompatible stories: one where pork sounds like a rising 'super food,' and another where some common pork products are tied to increased risks of bowel cancer.

This is a good example of how nutrition reporting can be used to distort the findings from one flawed study to producing misleading headlines that are not supported by the science: a specific, short‑term finding in a very controlled, plant‑forward setting is stretched into a general verdict on pork in a sensational headline, while ending with reminders of evidence on processed meat consumption and cancer risk.

We have contacted Zoe Hardy from the Daily Mail and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer

This fact-check is intended to provide information based on available scientific evidence. It should not be considered as medical advice. For personalised health guidance, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources

- Vaezi, S. et al. (2026). “Effects of Minimally Processed Red Meat within a Plant-Forward Diet on Biomarkers of Physical and Cognitive Aging: A Randomized Controlled Crossover Feeding Trial.”

- Gulec, S. & Erol, C. (2022). “The role of HDL cholesterol as a measure of 10-year cardiovascular risk should be re-evaluated.”

Mendes, V. et al. (2023). “ Intake of legumes and cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis.” - Marventano, S., et al. (2017). “Legume consumption and CVD risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis.”

- Thorisdottir, B., et al. (2023). “Legume consumption in adults and risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis.”

- Mo, Q. et al. (2025). “Plant-based diets and total and cause-specific mortality: a meta-analysis of prospective studies.”

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)