Why has meat become so expensive? Unpacking why plant-based protein could become the much cheaper option

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

By early 2025, many British shoppers had the same unsettling experience: the familiar pack of mince or chicken pieces suddenly felt like a luxury. At the same time, tins of beans and bags of lentils still cost roughly what people remembered from a few years ago.

According to a new Madre Brava briefing, that gut feeling is right – and it is not a one‑off “cost‑of‑living spike”. Their analysis, Meat’s affordability crisis, shows that meat in UK supermarkets has become dramatically more expensive than staple plant proteins, and that the gap has widened every year since 2020.

The ‘meat‑to‑beans’ gap, in numbers

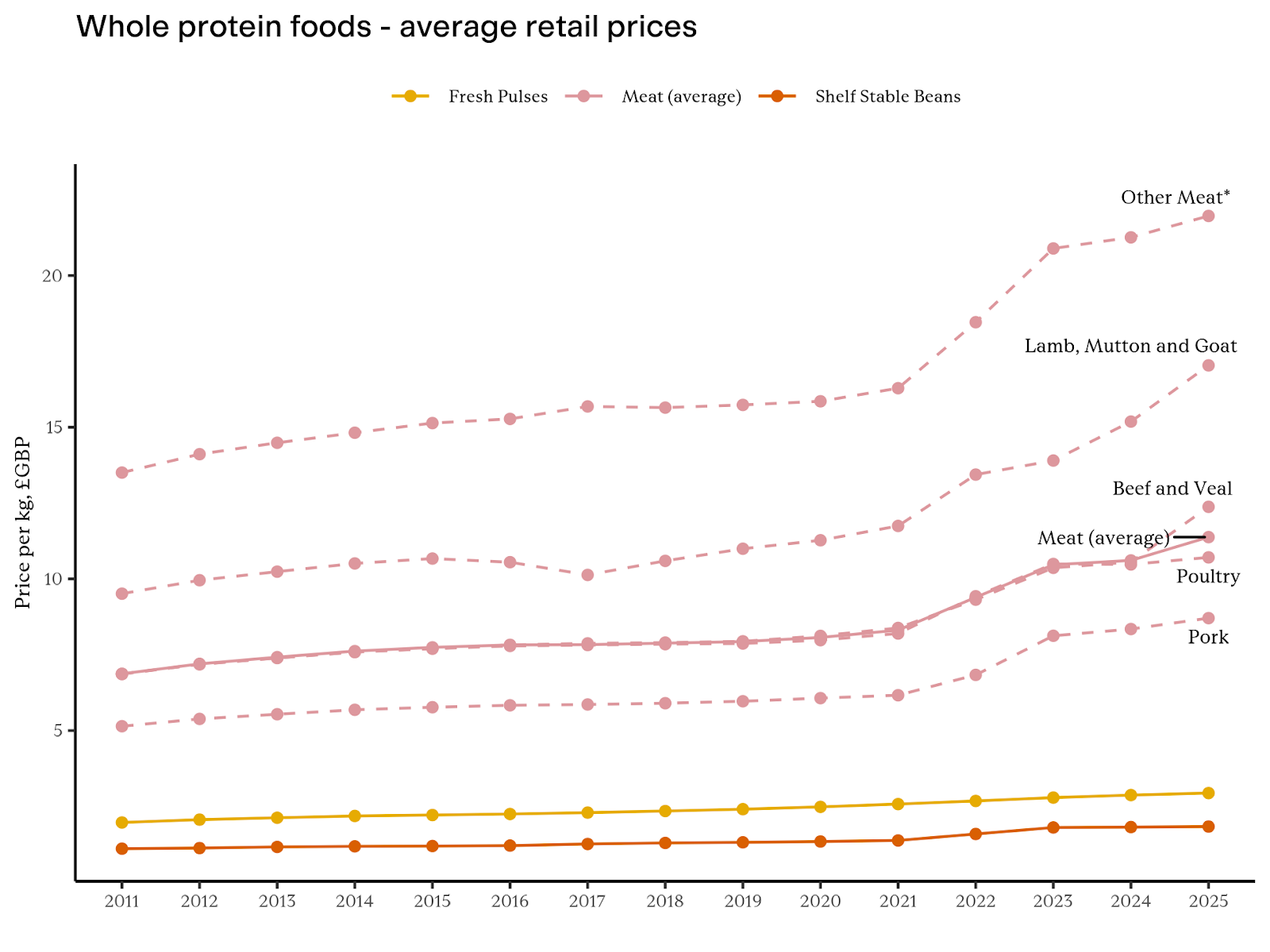

Using retail price data from Euromonitor, Madre Brava tracks a 15‑year time series of UK prices for meat and plant proteins. The results are stark:

- Between 2020 and 2025, the average price of meat on British supermarket shelves rose by £3.31 per kilogram, a jump of about 41%, reaching £11.38/kg.

- Over the same period, fresh pulses (like chilled lentils) rose by just £0.45/kg (18%) to £2.94/kg, and shelf‑stable beans by £0.60/kg to £1.84/kg.

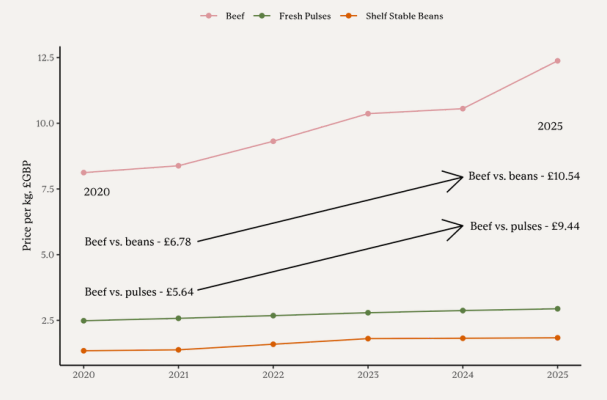

The crucial story is the gap:

- The price gap between shelf‑stable beans and beef widened from £6.78/kg in 2020 to £10.54/kg in 2025.

- For fresh pulses vs beef, the gap grew from £5.64/kg to £9.44/kg over the same period.

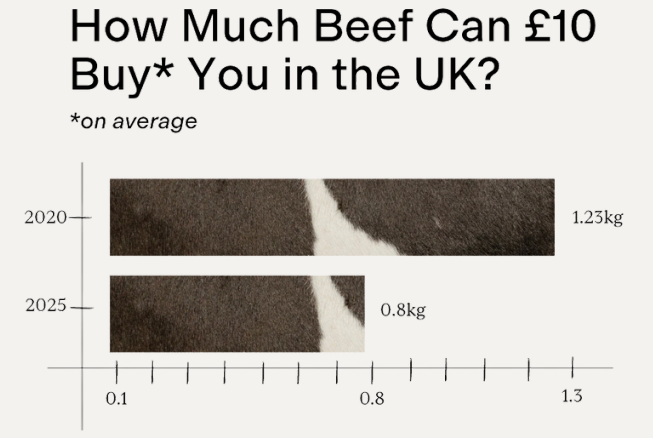

In practical terms, £10 that once bought around 1.23kg of beef in 2020 now only stretches to about 800g. The amount of beans or lentils you can buy with £10, meanwhile, has changed far less. That “meat‑to‑beans gap” is the core of what Madre Brava calls a meat affordability crisis.

Not just a blip: meat’s new “normal”?

A key finding from the briefing – echoed by Madre Brava’s director Nico Muzi in a widely shared LinkedIn explainer – is that this is not a short‑term spike. Their long‑term data suggest the UK is living through:

“A long‑term structural change in supply chains due to climate change, conflict and global trade disruptions.”

This matches the global picture. The FAO meat price index has reached record or near‑record levels in recent years, with beef and lamb among the biggest drivers. Analysts point to a similar mix of factors – weather extremes, feed and energy costs, trade shocks – pushing up global meat prices across major producing regions.

So while energy bills and some food items may ease as inflation falls, there is growing evidence that meat could stay relatively expensive, especially compared with pulses and other plant proteins.

Why is the price of meat rising so much faster than legumes

Madre Brava and other researchers highlight several overlapping reasons why meat is becoming less affordable than plant proteins.

Climate shocks hit livestock systems hard

Droughts, floods and heatwaves reduce pasture quality, damage feed crops and increase animal losses. In the UK and across Europe, drier summers mean cattle must be fed bought‑in feed earlier in the season, which raises costs. Globally, climate‑linked diseases such as bluetongue in livestock add further pressure.

Feed, energy and input prices bite more for meat

Raising animals is resource‑intensive. Farmers depend on feed crops like maize and soy, whose prices are themselves linked to drought and food prices. When fertiliser, fuel, and labour costs rise, the cumulative impact is far larger for beef or pork than for beans, which can be stored dried or canned and grown with fewer inputs.

Disease and trade disruptions shrink supply

Outbreaks of animal diseases lead to herd culls, export bans and tighter biosecurity – all of which disrupt supply and add costs that filter through to supermarket prices. Conflict and shipping disruptions, such as Red Sea route instability, further complicate global meat trade flows.

Market concentration keeps retail prices stubborn

In many countries, a handful of large meatpackers and retailers dominate slaughter, processing and shelf space. When there are bottlenecks or high demand, this can keep retail prices high even if farm‑gate prices for animals start to soften.

By contrast, beans, lentils and other pulses are less exposed: they tend to need less fertiliser and water, can be stored for long periods, and are less vulnerable to disease outbreaks. That makes them naturally more stable and affordable over time.

Beans, tofu and plant‑based meat: unexpected “winners”

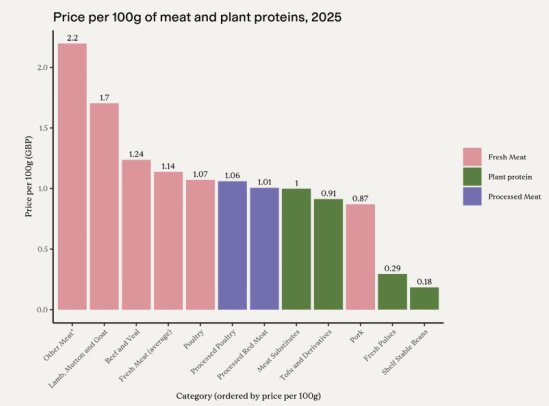

The Madre Brava briefing is not only about the rising cost of meat. It also documents how different types of plant protein are faring in UK supermarkets.

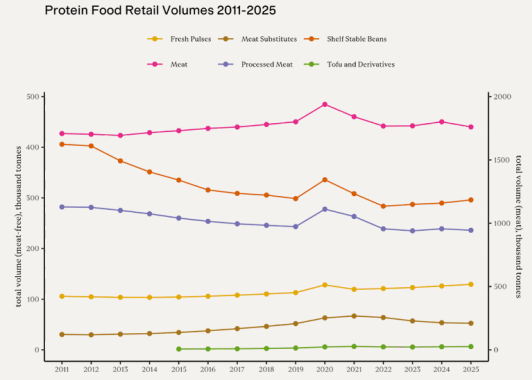

The Euromonitor data, summarised by Green Queen, show that:

- Whole‑food plant proteins, such as beans and pulses, have remained relatively cheap, with only modest price rises since 2020.

- The average price of tofu has actually fallen, and is now lower than most fresh and processed meats.

- Vegan meat alternatives have gone up in price, but much more slowly than animal proteins – making them, on average, cheaper than many conventional processed meats.

Madre Brava’s team found striking like‑for‑like examples. In the case of ready‑to‑cook convenience products such as chicken Kyiv:

Two‑pack plant‑based chicken Kyivs were cheaper than the chicken versions in almost all major supermarkets, including Tesco and Aldi.

For shoppers, that means it is no longer safe to assume that plant‑based versions are automatically more expensive. In several key categories, they undercut the meat equivalent.

How shoppers are already changing what’s in the trolley

When prices change this sharply, behaviour follows. Madre Brava’s analysis shows that as the meat‑to‑beans gap has widened:

- UK retail volumes of fresh meat have fallen well below pre‑pandemic levels.

- Sales of processed meat have continued their gradual decline.

- Meanwhile, consumption of beans and pulses has risen since 2022, with more Brits adding them to weekly shops.

This is supported by broader retail data and by consumer research covered by foodfacts.org, which has found that while some shoppers are cooling on expensive, highly processed plant‑based burgers, interest in affordable plant-based options remains robust.

There are health implications, too. Nearly 95% of UK adults fall short of recommended fibre intake, a shortfall linked to higher risks of heart disease, type 2 diabetes and some cancers. Pulses and many plant‑based proteins are naturally high in fibre and low in saturated fat, so a shift from large portions of red meat to more beans, lentils and tofu could support public health diets as well as household budgets.

Supermarkets in the spotlight

Madre Brava’s affordability work builds on its wider focus on the “protein transition” – the gradual shift from animal‑heavy diets towards more plant‑rich patterns. One of their central arguments is that supermarkets sit at the heart of that transition.

As a Madre Brava briefing on Europe's meat habit notes, just four supermarket giants – Ahold Delhaize, Carrefour, Lidl and Tesco – could, by replacing 50% of their beef, pork and chicken sales with pulses, tofu and plant‑based alternatives by 2030, save:

- 27.7 million tonnes of CO₂e per year – the equivalent of taking about 22 million cars off the road, and

- 91,000 km² of land – an area roughly the size of Portugal.

In the Netherlands, where all seven biggest chains have committed to shifting their protein sales towards more plants, retail meat sales have already fallen 16.4% since 2020, while plant proteins have risen.

By contrast, Madre Brava argues that UK supermarkets are lagging behind. Their recommendations for retailers, in light of the new affordability data, include:

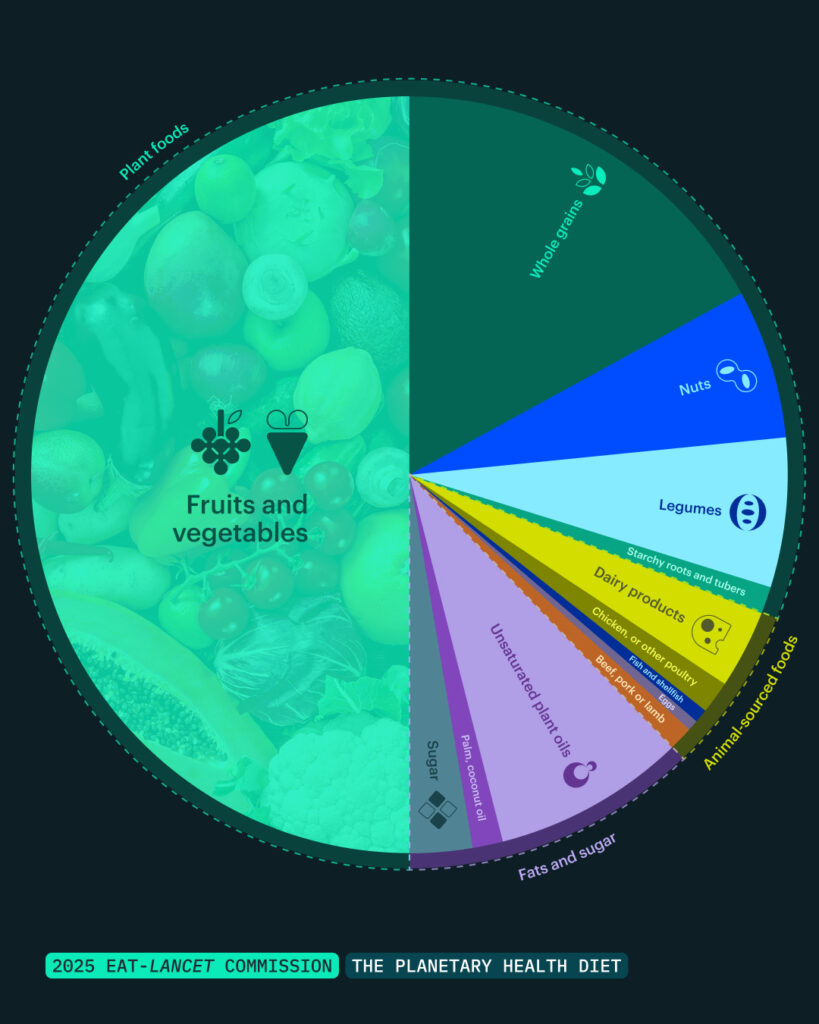

- Set clear plant/animal protein sales targets, at least aligning with the UK’s Eatwell Guide (and ideally a 60% plant / 40% animal split by 2030).

- Lower prices of plant‑based products to match or undercut meat (so‑called price parity) and place them side‑by‑side with meat in store.

- Promote recipes and ranges that use smaller amounts of meat combined with beans, grains and vegetables, rather than centring every meal on a large portion of meat.

- Support farmers in a just transition, including paying fair prices for both food and ecosystem services, and pushing for subsidy reform that doesn’t lock producers into high‑emission livestock systems.

In short, supermarkets can either amplify the affordability crisis by clinging to a meat‑heavy status quo, or soften it by making plant‑rich shopping the easiest, cheapest default.

What this means for fairness – and for policy

Rising meat prices hit some households much harder than others. Lower‑income families spend a larger share of their income on food, so increases in the price of staple items such as mince, chicken thighs, or sausages bite deeply into already tight budgets.

Researchers working on a just transition for the meat sector warn that without support, poorer households will be disproportionately affected by higher meat prices, particularly where access to fresh fruit, vegetables and plant proteins is limited. They argue that governments need to:

- Reform agricultural subsidies away from industrial meat overproduction and towards diverse, sustainable farming that includes pulses and horticulture.

- Protect vulnerable consumers, for example by expanding healthy food vouchers, school meal schemes and targeted social protection so that nutritious foods remain within reach.

- Align dietary guidelines, public procurement and retailer regulation so that the “default” meals in schools, hospitals and canteens are closer to plant‑rich, planetary‑health diets.

For policymakers, the Madre Brava affordability data is a warning signal: if structural pressures on meat prices continue, failing to invest in accessible plant‑based options could deepen both health inequalities and climate risks.

Practical ways households can respond now

None of this means families must abandon meat overnight. But in a world where beef and other meats look set to stay relatively pricey, there are pragmatic ways to keep favourite flavours while shrinking the meat bill:

- Make meat a flavouring, not the whole meal: Stretch mince in chilli, Bolognese or shepherd’s pie with lentils or beans. Combine small amounts of chorizo or bacon with chickpeas or white beans in stews and soups.

- Try one or two “bean‑centric” meals a week: Dishes built around dals, bean chillies, lentil soups or tofu stir‑fries are often substantially cheaper per portion than meat‑heavy equivalents, especially when made from dried pulses bought in bulk.

- Use plant‑based products strategically: Some plant‑based sausages, burgers and nuggets are now cheaper than processed meat options. They can be convenient “bridge” foods for households exploring lower‑meat meals, even if they’re not whole foods.

- Look for price‑savvy swaps: In categories like chicken Kyivs, breaded fillets or sausages, it’s increasingly worth checking labels and doing quick per‑kg comparisons – you may find the plant‑based version is the budget choice.

- Double‑up on fibre and protein: Pair smaller amounts of meat with fibre‑rich sides – lentil salads, bean mash, wholegrain breads – to keep meals filling and support long-term health.

foodfacts.org has previously examined why consumers are moving away from plant-based meat towards simpler proteins, and how to balance budget, health and sustainability when choosing between meat, ultra‑processed alternatives and whole‑food plants.

Looking ahead: reading the signal in the bill

For years, the idea that “meat is getting more expensive” was easy to dismiss as anecdote or seasonal fluctuation. Madre Brava’s meat affordability crisis briefing gives that story hard edges: numbered price tags, widening gaps, and a clear message that the causes of meat price rises – climate change, conflict, fragile supply chains – are not going away.

The weekly shop is often where abstract issues like climate policy or global trade feel most tangible. The latest data suggest that, without deliberate action, the default British diet – centred on generous portions of cheap meat – will become harder and harder to sustain.

The good news is that solutions already exist. Beans, lentils, tofu and some plant‑based products are quietly becoming the best value proteins in the aisle. Supermarkets and governments have powerful levers to pull, from plant‑forward sales targets and price parity to subsidy reform and safety nets for low‑income households.

Whether meat remains an everyday staple or becomes more of an occasional extra will depend on how quickly those levers are used – and whether the affordability crisis is treated as a passing inconvenience, or as a sign that our food system needs a decisive, plant‑rich reset.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources

- AgroReview (20 October 2025). Global meat prices reach record levels: Reasons for the increase.

- BestFoodFacts.org (13 September 2015). Drought: What does it mean for food?

- FarmAction (10 September 2025). Meatpacking: Four Corporations, Total Control

- foodfacts.org (7 April 2025). Unpacking the shift: Why consumers are moving away from plant-based meat.

- foodfacts.org (18 November 2025). Ultra-processed foods, plant-based meat and your health.

- Green Queen (7 December 2025). Soaring meat prices drive Brits towards more affordable plant proteins.

- Just Food (8 August 2025). Global meat prices rise to all-time high amid US, China demand – FAO

- Madre Brava (3 December 2025). Meat’s affordability crisis – the price gap with plant proteins is widening by the year.

- Madre Brava (n.d.). Europe’s top supermarkets race towards plant-rich diets – but the finish line is far

- Spiro A, Bardon L, Fanzo J, Hill Z, Stanner S, Traka MH. Every Person Counts in a Fair Transition to Net Zero: A UK Food Lens Towards Safeguarding Against Nutritional Vulnerability. Nutr Bull. 2025 Dec;50(4):683-702. doi: 10.1111/nbu.70032. Epub 2025 Oct 16. PMID: 41099170; PMCID: PMC12621166.

- SEI (November 2022). A just transition in the meat sector: why, who and how?

- The Food Foundation (November 2024). The state of the nation’s food industry 2024.

- The Food Foundation (14 July 2025). UK still failing to meet basic dietary guidelines

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)