How GLP-1 drugs are reshaping what we eat and why it matters for the planet

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

You've probably heard of Ozempic or Wegovy by now. These weight loss medications have been everywhere, from celebrity gossip columns to serious medical journals. But there's a story developing that most people aren't talking about yet: these drugs aren't just helping people lose weight. They're changing what people want to eat. And when millions of people start choosing different foods, that has consequences for the entire food system.

Over the next decade, an estimated 40 million people worldwide could be using these medications. Early evidence shows that people taking these drugs are eating less beef, choosing more vegetables, and turning away from processed snacks. If that pattern holds, it could meaningfully reduce the environmental damage caused by industrial food production.

What are GLP-1 drugs, and where did they come from?

The story of GLP-1 starts with a simple question: Why do we feel full when we eat?

For decades, scientists knew the answer involved hormones released by the gut. In the 1980s, researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital discovered a hormone called GLP-1, a natural signalling molecule that tells your brain you're satisfied and should stop eating.

This was interesting science, but nobody knew what to do with it. Then researchers had an idea: what if you could amplify this natural signal? What if you could make someone's body feel genuinely full on less food?

The problem was technical. Your body naturally breaks down GLP-1 within minutes, which makes it useless as a medication. It took chemists decades to crack this puzzle. Finally, in 2017, a drug called Ozempic arrived, approved by the FDA to treat type 2 diabetes. A few years later, the same medication was approved for weight loss under the brand name Wegovy. Then in 2022, Mounjaro hit the market, a next-generation version that worked even better.

Here's how these drugs work: when you eat, your gut releases natural chemicals that tell your brain "we've had enough." These chemicals slow down digestion, signal satisfaction, and reduce cravings. In people with obesity or type 2 diabetes, this system gets broken. The signals get ignored, and the brain never gets the "stop eating" message.

These medications flood your body with amplified versions of these natural signals. The result? People feel genuinely satisfied with less food, and their cravings, especially for junk food, simply disappear.

How are GLP-1 drugs changing what people eat?

Researchers surveyed nearly 2,000 people taking these medications, and patterns are starting to emerge.

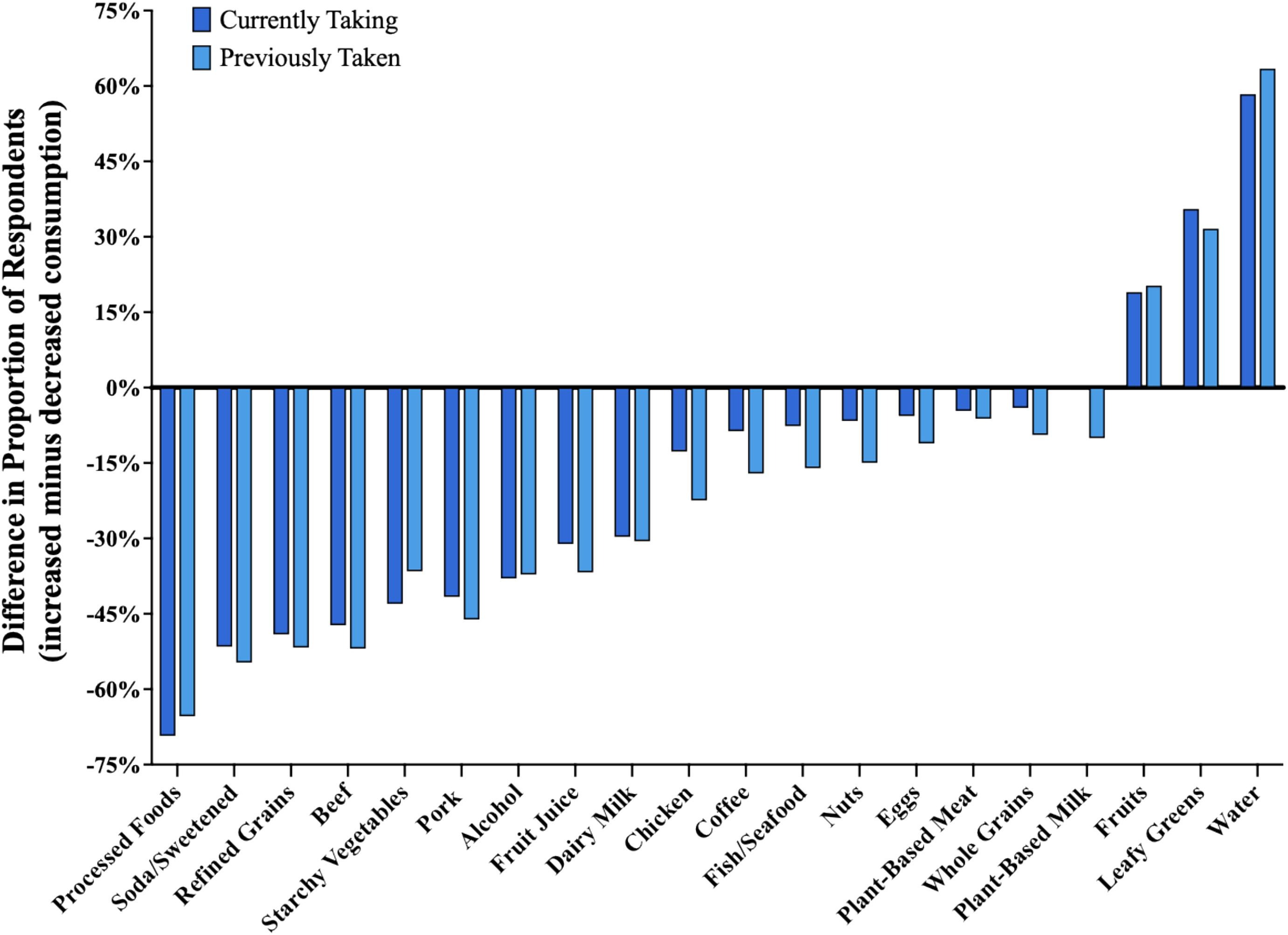

Over 70% of users reported eating less junk food, including packaged snacks, sugary drinks, frozen meals, and fast food. This matters because these foods are engineered to be irresistible. They contain combinations of salt, sugar, and fat designed to make you eat more than you need. GLP-1 medications essentially turn off the brain's reward response to these foods. Consumers stop eating these foods, not because they're forcing themselves, but because the food becomes unappealing.

About half of users are eating less beef and pork. This matters because producing a hamburger requires vastly more resources and generates far more emissions than growing vegetables. Beef farming accounts for roughly 3.3% of all US greenhouse gas emissions. As one researcher studying this trend put it: "I don't see any way consumption of beef isn't decreased" as these drugs become more common.

Interestingly, the only foods showing increased consumption are fresh produce: fruits, leafy greens, and vegetables. Rather than eating a bit of everything less, users are actively shifting toward healthier choices.

Households with someone taking these medications spend about 6% less on groceries overall, and up to 9% less for higher-income families. Scale that up: by 2031, this could mean 60 to 90 billion dollars less spent annually on food in the US alone.

For the processed food industry, this is a nightmare. These companies have built their entire business model on foods that hijack your appetite, making you eat more than your body needs. Now, GLP-1 drugs are neutralizing that approach.

What does this mean for the environment?

When someone taking GLP-1 eats fewer calories, they're generating fewer emissions from food production. A 2025 study found that GLP-1 users produce about 695 kilograms less of CO2 equivalents per year just from consuming fewer calories. That's equivalent to the emissions from about 1,700 miles of car driving.

But the dietary shift, especially the reduction in beef, is where the real environmental win happens. Beef production is remarkably resource-intensive. Raising cattle for meat generates enormous amounts of methane, a potent greenhouse gas. It also requires massive amounts of water and typically involves clearing forests for grazing land or growing feed crops.

.png)

The comparison is striking: plant-based proteins create 40 to 100 times fewer emissions than beef or lamb. Even more impressive, newer protein alternatives like proteins grown from microbes or fungi produce 62 times less emissions than animal proteins while using 2,000 times less land.

Even grass-fed beef, often marketed as the "sustainable" option, emits 10% more greenhouse gases per kilogram of protein than industrial beef when you account for methane's potency.

If just 10% of overweight adults and 20% of obese adults in the US start using these medications, total calorie consumption would drop by about 3%. That's 20 billion fewer calories consumed every single day in a single country. That reduction creates breathing room in the agricultural system. Land could transition to growing nutrient-dense vegetables and plant-based proteins, or even be restored to natural ecosystems.

The challenges and questions ahead

Food companies are responding to these changes, but not always in the right way. Nestlé is developing "GLP-1 friendly" packaged foods, convenient frozen meals and snacks designed for people eating less.

History suggests we should be cautious. During the gluten-free craze a decade ago, companies flooded shelves with "gluten-free" products that were often less healthy and more expensive than regular options. The same thing happened during the fat-free craze of the 1990s, when companies replaced natural fats with added sugars and refined carbs.

The smarter path would be innovation in whole foods: high-protein beans and lentils, whole grains, and nutritious plant-based options that require minimal processing. But that requires long-term thinking and investment.

Currently, GLP-1 drugs are expensive and not universally accessible. Wealthy people in developed countries have them. Most of the world doesn't. The environmental benefits only materialize if adoption extends broadly. Recently, GLP-1 pills have been approved for the US and Canadian markets. This is sure to accelerate the adoption of this medication. Folks who don’t like injections, or places where price and cold-storage were a barrier, will now be able to access this medication.

The food system won't automatically shift toward sustainability just because demand changes. Farmers need transition support to shift from commodity crops to regenerative practices. Policymakers need to set standards ensuring that "GLP-1 friendly" foods are actually nutritious. Without policy guardrails, the environmental opportunity could be missed.

The rise of GLP-1 medications represents something rare: a health intervention that could improve environmental sustainability. The evidence is mounting: people taking these drugs eat fewer calories, choose less beef, avoid processed foods, and eat more vegetables. At scale, these changes could meaningfully reduce greenhouse gas emissions and food waste. But this isn't automatic. One thing is certain: the food system is changing. Whether that change points toward sustainability or simply toward a different set of problems depends on the choices we make in the next few years.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources

- BBC (16 May 2019). Ultra-processed foods 'make you eat more'

- CNBC (10 January 2026). 2026 is the year of obesity pills. Here's how they could reshape the GLP-1 market

- David A. D’Alessio, Steven E. Kahn (1 January 2025); The Development of Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 as a Therapeutic: The Triumph of the Lasker Award for Obesity Is a Victory for Diabetes Research. Diabetes; 74 (1): 1–3. https://doi.org/10.2337/dbi24-0046

- Dilley, A., Adhikari, S., Silwal, P., L. Lusk, J., & McFadden, B. R. (2025). Characteristics and food consumption for current, previous, and potential consumers of GLP-1 s. Food Quality and Preference, 129, 105507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2025.105507

- Foodfacts.org (29 October 2025). Cows won’t cool the planet – and saying they can misses the point

- Foodfacts.org (28 May 2025). “Net zero beef?” Why sustainability claims need more than headlines

- Foodfacts.org (19 June 2025). What does “grass-fed” really mean? The meaning behind the label

- Green Queen (27 May 2025). GLP-1: Does Ozempic Make You Dislike Beef?

- Kalaitzandonakes, M., B. Ellison, T. Malone and J. Coppess (14 March 2025). "Consumers’ Expectations about GLP-1 Drugs Economic Impact on Food System Players." farmdoc daily (15):49, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- Malila, Y., Owolabi, I. O., Chotanaphuti, T., Sakdibhornssup, N., Elliott, C. T., Visessanguan, W., Karoonuthaisiri, N., & Petchkongkaew, A. (2024). Current challenges of alternative proteins as future foods. Npj Science of Food, 8(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-024-00291-w

- Nestle (21 May 2024). Nestlé introduces Vital Pursuit brand to support GLP-1 users in the US

- Pelton, R. E., Kazanski, C. E., Keerthi, S., Racette, K. A., Gennet, S., Springer, N., Yacobson, E., Wironen, M., Ray, D., Johnson, K., & Schmitt, J. (2024). Greenhouse gas emissions in US beef production can be reduced by up to 30% with the adoption of selected mitigation measures. Nature Food, 5(9), 787-797. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-01031-9

- Roland Berger (8 May 2025). GLP-1: Fad or future?

- Sentient Media (8 January 2026). GLP-1 Users Lose Weight, and Their Taste for Meat

- The Food Institute (5 June 2025). Steaks Are High: GLP-1 Drugs Reshape Beef Demand

- The New York Time (12 January 2026). Is Grass-Fed Beef Really Better for the Climate?

- UBS (n.d.) GLP-1: A medication worth $126 billion in sales by 2029?

- US News (28 August 2025). GLP-1 Drugs Are Good For Climate Change, Heart Study Says

- Wikipedia (n.d.) Semaglutide

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)