UK junk food advertising ban finally launches, but the fight is far from over

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

After years of delays and industry lobbying, new restrictions on junk food advertising targeting children will take effect on 5 January 2026. The regulations, which ban high-fat, salt and sugar (HFSS) products from television before 9pm and from paid online advertising entirely, mark a significant milestone for public health campaigners. But for youth activists at Bite Back 2030, who have fought for this moment since 2020, celebration comes with a stark warning: pushing junk food ads off screens just pulls them onto streets.

The journey to this watershed moment reveals both the power of youth activism and the persistent influence of industry lobbying on government policy. The Health and Care Act 2022 received Royal Assent on 28 April 2022, initially scheduling restrictions for 1 January 2023. Yet implementation was delayed multiple times, first to January 2024, then October 2025, and finally January 2026, each postponement attributed to industry pressure and technical clarifications demanded by food and advertising companies.

How industry lobbying watered down protections

While Bite Back celebrates this legislative victory as evidence that youth-led movements can influence policy outcomes, the final regulations represent a significantly diluted version of what was initially envisioned. In testimony to the Health and Social Care Committee in November 2025, Bite Back's Head of Policy and Research Nika Pajda explained how "industry's successful lobbying has led to its delay and watering down, which means young people will continue to be exposed to unhealthy ads".

The most significant compromise came through The Advertising (Less Healthy Food and Drink) (Brand Advertising Exemption) Regulations 2025, which explicitly exempted brand advertising from restrictions. This exemption, inserted after coordinated pressure from food manufacturers and advertising firms, allows companies to continue promoting their brands, provided no specific HFSS product is depicted. Public health bodies, including the Obesity Health Alliance, expressed disappointment that the government "appears to be caving to industry pressure," with Obesity Health Alliance Director Katharine Jenner noting the delays represented "a coordinated attack by companies selling the unhealthiest food and drinks".

Beyond the brand advertising loophole, the regulations contain another glaring omission: they don't cover out-of-home advertising at all. This gap leaves billboards, bus stops, and other street advertising entirely unregulated, precisely where Bite Back's research shows the problem is most acute.

The street advertising inequality crisis

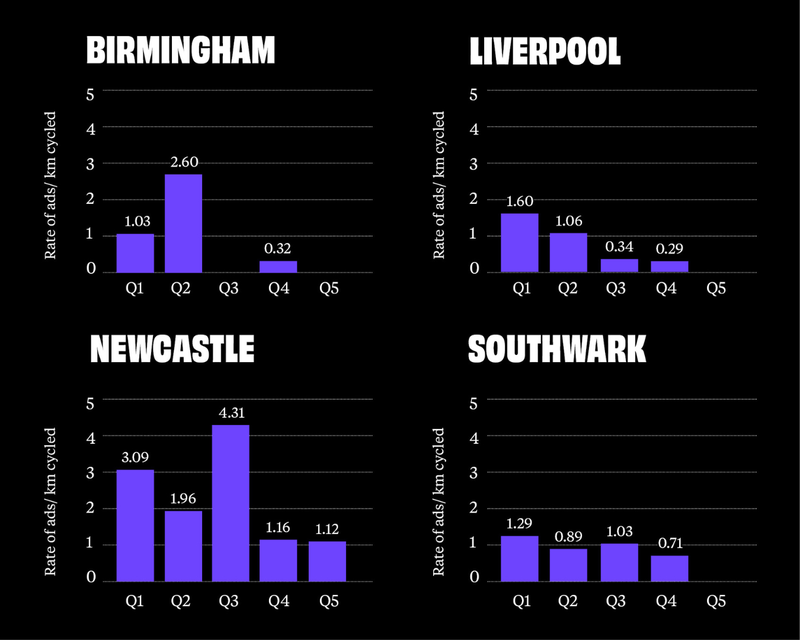

Working with researchers at the University of Liverpool, Bite Back documented how food and drink companies spent over £400 million on street advertising in 2024 alone. Major fast food chains and snack manufacturers, including McDonald's, PepsiCo, KFC, Coca-Cola, Mars, Mondelez and Red Bull, dominated this spending. Surveying Newcastle, Liverpool, Birmingham and Southwark, researchers found that 57% of all food and drink advertisements were for unhealthy products.

More troubling still is where these advertisements appear. Junk food ads are six times more likely to appear in the most deprived areas compared to the wealthiest neighbourhoods. In Newcastle, three-quarters (77%) of all food and drink advertisements were for unhealthy products. Nika Pajda's parliamentary testimony highlighted this "stark inequality," noting that 44% of HFSS adverts were located in the UK's most deprived areas compared to just 4% in the most affluent.

This pattern isn't accidental. Research on outdoor advertising and inequality shows that advertising companies deliberately target high-traffic areas in underserved communities, where residents are disproportionately exposed to marketing for products contributing to obesity. A BMJ investigation revealed how advertising firms lobby cash-strapped councils by warning they would lose up to 30% of advertising income if they restrict junk food ads.

Why this matters now

The stakes couldn't be higher. Latest government data shows that 10.5% of reception-age children and 22.2% of year 6 children in England are living with obesity. Over a third of children leave primary school at risk of food-related illness. These weight issues cost the NHS an estimated £340 million annually.

Evidence demonstrates that advertising restrictions work. When Transport for London banned junk food advertising across its entire network from February 2019, research showed it was linked to lower purchases of unhealthy food and drink. The policy, which covered the Underground, buses, Overground and other TfL services, received overwhelming support from Londoners, with 82% backing the proposals.

Bite Back is now calling on Health Secretary Wes Streeting to extend advertising restrictions to out-of-home media, following the TfL model nationwide. Until then, youth activists will continue their #CommercialBreak campaign, which saw them purchase billboard space to give children a break from junk food marketing.

As seventeen-year-old Bite Back activist Farid from Manchester explains: "Since the day I was born, I've been targeted. The truth is, this isn't normal. It isn't normal to feel trapped and surrounded by junk food ads".

The upcoming ban represents progress, evidence that sustained youth activism can shift policy. But with outdoor advertising still flooding Britain's streets, particularly in its poorest communities, the campaign for comprehensive protection is only just beginning.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources

- Adfree Cities (March 2024). “UNAVOIDABLE IMPACT” How outdoor advertising placement relates tohealth and wealth inequalities.

- BBC (24 February 2022). How outdoor advertising can deepen inequality.

- Bite Back 2030 (2025). Give Us A Commercial Break.

- Bite Back 2030 (12 November 2025). Bite Back returns to Parliament to keep up the pressure.

- BMJ Group (8 April 2025). Bans on outdoor junk food ads derailed by industry lobbying.

- Food Active (15 December 2025). Blog: Protecting children or protecting profits? The journey to restrict less healthy adverts.

- Gov.uk (2 December 2024). Junk food ad ban legislation progresses to curb childhood obesity

- Gov.uk (4 June 2025). Restricting advertising of less healthy food or drink on TV and online: products in scope

- Gov.uk (3 November 2025). Government acts to tackle rising childhood obesity epidemic.

- Health Media Blog (5 December 2024). Here are the facts about our junk food advertising ban.

- Marketing Week (21 May 2025). Government delays less healthy ad ban to formally exempt brand advertising.

- Nesta (22 December 2025). Six things we learnt from the latest childhood obesity data for England.

- NIHR Evidence (28 June 2024). TfL advertising ban lowered purchases of unhealthy food.

- Obesity Health Alliance (22 May 2025). OHA Comment: Advertising Restrictions - Delayed and Watered Down.

- Obesity Health Alliance (8 September 2024). Blog: "Why is my local area a giant ad space for junk food?".

- Oxford Health BRC (30 September 2025). Underweight children cost the NHS as much per child as children with obesity.

- Taylor Wessing (23 September 2025). HFSS promotion, placement and advertising: where are we now?.

- Transport for London (November 2018). Mayor Confirms Ban on Junk Food Ads on Transport Network.

Wiggin (12 November 2025). What are the new "less healthy" HFSS advertising restrictions?

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)