How fish farming created global seafood demand – instead of reducing pressure on wild fish

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

How aquaculture creates, not meets, demand

Industrial aquaculture presents itself as a response to rising global seafood demand, marketed as a responsible way to relieve pressure on wild fisheries while feeding a growing population. The pattern documented in recent research shows the opposite: producers helped create that demand by reshaping science, policy, and culture in ways that favored more sea animal consumption, especially in high-income countries.

Total seafood consumption has risen sharply with the expansion of aquaculture. While direct human consumption of wild-caught fish has remained broadly stable, wild capture has not declined, indicating that aquaculture added new supply instead of replacing fishing pressure. Companies achieved this by promoting fish farming as essential for food security and sustainability while using political influence and public relations to normalize everyday consumption of fish like salmon, where it had previously been occasional.

The displacement myth and supply-driven demand

Fish farming companies often claim they are meeting humanity’s growing hunger for seafood by replacing wild-caught fish with farmed alternatives. This narrative hides two key facts: first, aquaculture still relies on wild fish for feed, and second, cheap farmed fish from factory farming operations has helped trigger a surge in overall fish consumption rather than a shift away from wild fish.

A 2019 study in Conservation Biology by Stefano Longo et al found no evidence that aquaculture growth reduces wild capture volumes in most cases. In cross-national time series models that controlled for factors like population, GDP, and geography, eight out of nine robust models showed no relationship between the expansion of aquaculture and declines in wild catch. (Only one model reports displacement of wild-capture fish by farmed fish, but the authors caution that it fits the data poorly because it is driven by a small number of highly influential countries whose extreme production patterns disproportionately shape the results.) In a subsequent 2024 study in Science Advances, Longo and Yorke argue that in a profit-driven global market, a new production system rarely replaces the old; instead, both grow together, similar to how the rise of petroleum intensified rather than reduced whaling activity. Whaling only collapsed in the late 20th century because whale populations were so depleted that hunting was no longer economically viable, not because substitutes made it unnecessary.

According to Longo and York, economic theory helps explain this outcome: making a product cheaper and more available tends to increase total consumption, not reduce it. Confining large numbers of fish in net pens to produce low-cost sea animal products has created supply-driven demand, where the industry-manufactured abundance of farmed salmon and other species stimulates appetite for fish that would not otherwise exist. Rather than serving food-insecure regions, most growth has been concentrated in wealthy markets that already consume more protein than nutritionally necessary.

Fisheries data support this theory: According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), in 1980, roughly 34% of assessed fish stocks were classified as “underfished,” about 56% as “fully exploited,” and around 10 % as “overfished.” Today, after more than 40 years of aquacultural growth, those proportions have worsened, rather than improved: only about 7% of global stocks remain “underfished,” approximately 35% are “overfished,” and the majority are classified as “fully exploited,” meaning there is little or no margin for additional fishing pressure without destabilizing the population. If aquaculture were relieving pressure on wild fisheries, even this permissive management framework—designed to maximize harvest rather than ecological health—would show improvement. Instead, FAO utilization data indicate that while the volume of wild-caught fish eaten directly by humans has remained relatively stable, total wild capture has not declined and aquaculture increasingly depends on wild fisheries for feed. As Longo and York note, the resulting plateau in global fishing reflects biological limits, not displacement by fish farming.

Overconsumption and protein inefficiency

The rapid expansion of industrial aquaculture did not simply meet pre-existing dietary needs—it helped drive a sharp increase in sea animal consumption, particularly in high-income countries. Since industrial aquaculture took off, per capita sea animal intake has more than doubled, rising from about 9.1 kilograms per person per year in the 1980s to 20.7 kilograms in 2022. Because the global population also roughly doubled in that period, total sea animal consumption increased nearly fourfold, showing that overall use of aquatic animals grew far faster than population growth alone can explain.

This surge does not reflect unmet nutritional needs. In high-income countries, average protein intake already exceeds dietary requirements, so additional animal protein does not address food security issues but instead reinforces overconsumption. For lower-income countries, much industrial expansion in these regions is export-oriented for wealthier markets and does not primarily serve food-insecure populations. As the FAO notes, hunger is driven by access and inequality rather than insufficient protein supply, and increased production alone does not guarantee improved nutrition outcomes.

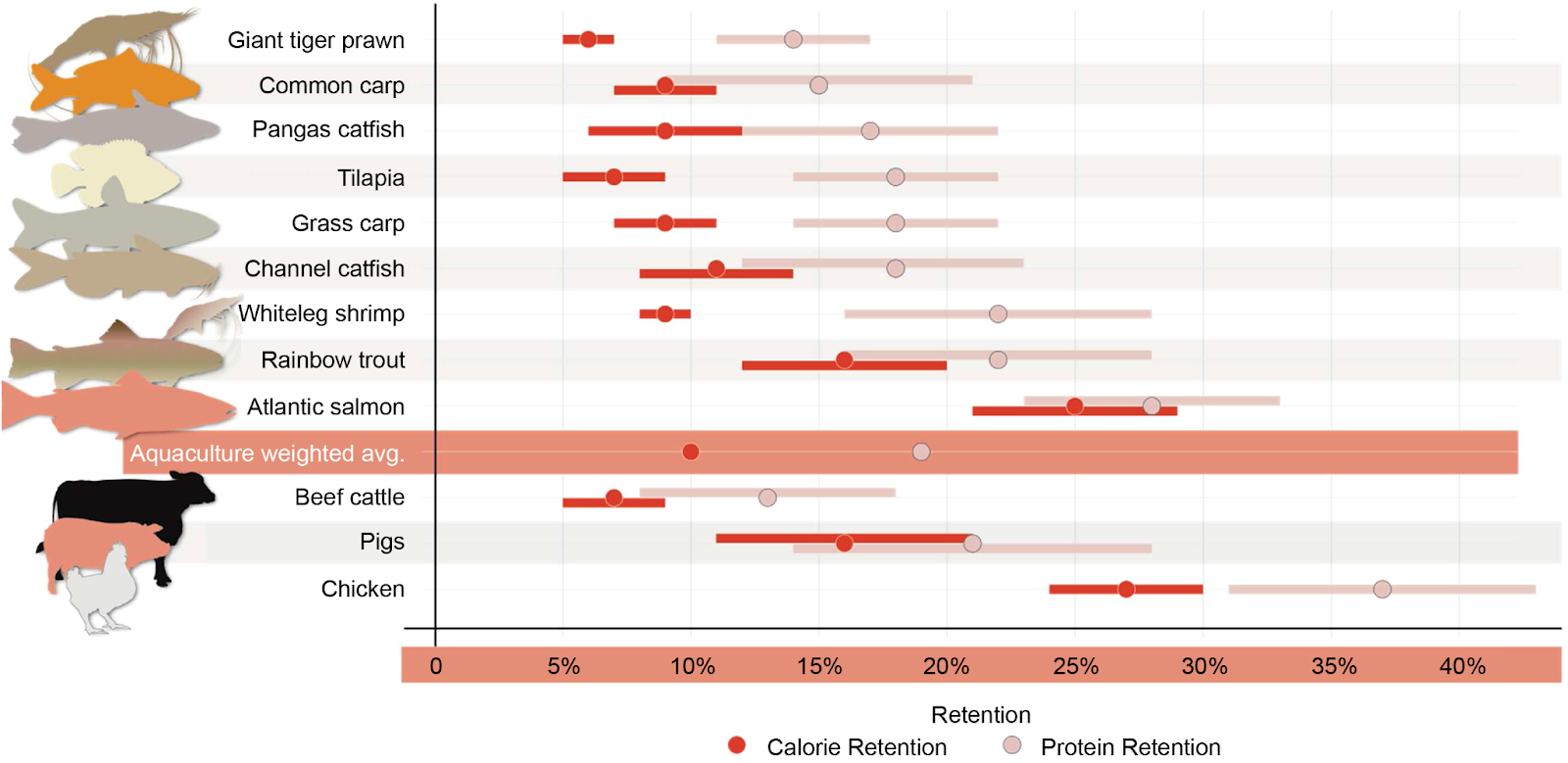

At the same time, aquaculture is an inefficient way to convert feed into human nutrition. Research from the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future finds that across nine major farmed aquatic species, only about 19% of protein and 10% of feed calories are retained for human diets, losses comparable to or worse than other industrial animal systems. This means the vast majority of nutrients fed into aquaculture are lost to metabolism, waste, or discarded biomass rather than nourishing people. Together, these findings show that fish farming expands total animal protein supply without delivering efficient nutrition, making it a net drain on global food resources rather than a credible solution to hunger.

Building political cover for expansion

To scale up globally, aquaculture companies first needed political legitimacy and regulatory space to grow with minimal constraints. Instead of earning this through consistent environmental performance, the industry worked to shape research agendas and policy frameworks that cast fish farming as indispensable to solving overfishing and feeding the world.

Norway’s salmon sector illustrates this strategy clearly. From early on, the industry invested heavily in research and promotion that framed salmon farming as a sustainability success story, channeling money into universities and research institutes through mechanisms such as the Norwegian Seafood Research Fund (FHF). Industry-linked funding prioritized questions of growth, efficiency, and technical optimization, while sidelining cumulative ecological impacts, feed dependence, and systemic risks. These findings were then promoted by Norwegian officials and industry representatives in international bodies, including the FAO, helping anchor aquaculture in influential policy texts like the 1995 FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries and the 2000 Kyoto Declaration on Aquaculture.

Today, major development lenders such as the World Bank rely on this framing when projecting tens of millions of additional tonnes of aquaculture production in the name of food security. This policy endorsement provides powerful cover for continued expansion, even as evidence accumulates that the system intensifies rather than alleviates ecological pressure.

In Chile, where Norwegian capital helped build one of the world’s largest salmon industries, companies secured long-term coastal concessions that function much like private property rights over sections of the ocean. During the 2016 Chiloé red tide crisis, which devastated local fisheries, authorities under industry pressure authorized the offshore dumping of thousands of tonnes of dead farmed salmon; later analysis suggested that this decision likely worsened the harmful algal bloom by adding nutrients and organic matter to already stressed waters.

Undermining critical science

When independent scientists published research that challenged the industry’s narrative, fish farming interests often responded by attacking credibility rather than addressing the underlying issues. After a 2004 paper in Science found that farmed salmon, particularly from Scotland and the Faroe Islands, contained higher levels of contaminants such as PCBs, dioxins, toxaphene, and dieldrin than wild salmon, the industry mobilized to discredit the findings.

Front groups, including Salmon of the Americas and the Society for the Positive Awareness of Aquaculture, launched public relations campaigns and pressured regulators to downplay the risks, even though follow-up risk assessments suggested that eating farmed salmon at the then-recommended levels could increase cancer risk. Regulatory agencies in the United Kingdom and the European Union maintained existing consumption advice, illustrating how political and economic pressure can blunt the impact of public health warnings in this sector.

Designing demand through marketing and culture

Once political backing and loose regulatory conditions were in place, salmon producers turned to consumer marketing to ensure that rapidly expanding supply would be matched by demand. These campaigns did more than advertise; they worked to redefine norms around when, how, and why people eat fish, shifting salmon from a rare treat to an everyday staple.

In Norway, the Norwegian Seafood Council (NSC) ran a nationwide campaign in the 1980s that presented salmon as suitable “for workdays and for feasts,” recasting it as an all-purpose, year-round meal rather than an occasional luxury. This cultural repositioning opened the door for intensive salmon farming to flood domestic markets while maintaining an image of modernity and healthfulness.

One particularly influential initiative, often described as Project Japan, targeted sushi culture. Japanese diners had historically avoided raw salmon, associating it with parasites, but Norwegian promoters organized tasting events, chef outreach, and media messaging to rebrand salmon as safe and desirable in sushi. According to a recent NSC Japan study, as sushi later globalized, this manufactured preference for salmon traveled with it, creating high-margin markets where none had previously existed.

In the United States, the Norwegian Seafood Council’s Joint Marketing Program co-funds supermarket labeling such as “Seafood from Norway” and “Responsible Seafood,” signage that can be interpreted as independent sustainability endorsements rather than industry-sponsored marketing. With this support, farmed salmon climbed to become one of the most consumed sea animals in the country, rising from negligible levels a few decades ago to 3.22 pounds per person in 2022.

These strategies show that the fish farming industry did not simply respond to neutral consumer demand; it actively engineered that demand through policy influence, selective science, and sophisticated marketing campaigns. Instead of replacing wild fisheries, aquaculture expanded the entire seafood category, driving higher overall consumption while leaving fishing pressure largely unchanged. The narrative that fish farming would relieve overfishing and improve food security has been used to justify rapid expansion, even as wild fish populations remain under strain and hunger persists. The result is rising overconsumption of a feed-intensive, inefficient animal protein that accelerates ecological damage across oceans, land, and climate—without delivering the benefits it promises.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

Sources:

- Aquaculture Accountability Project (January 2026). The Myth of "Sustainable" Aquaculture

- Andreoli, V., Bagliani, M., Corsi, A., Frontuto, V., Andreoli, V., Bagliani, M., Corsi, A., & Frontuto, V. (2021). Drivers of Protein Consumption: A Cross-Country Analysis. Sustainability, 13(13). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137399

- Armijo, J., Oerder, V., Auger, P., Bravo, A., & Molina, E. (2019). The 2016 red tide crisis in southern Chile: Possible influence of the mass oceanic dumping of dead salmons. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 150, 110603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110603

- Changing Markets Foundation (April 2019). “Until the Seas Run Dry: How industrial aquaculture is plundering the oceans”

- Foodfacts.org (28 January 2026). Fish farming's hidden truth: How aquaculture actually intensifies overfishing of wild species

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (1995). Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. Rome: FAO.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2000). “Kyoto Declaration on Aquaculture.” In Aquaculture Development Beyond 2000: The Bangkok Declaration and Strategy. Rome: FAO/NACA.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2024). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024: Blue Transformation in Action. Rome: FAO.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (n.d.). The Norwegian Fishery and Aquaculture Industry Research Fund (FHF). In Industry organizations and research institutions in the Norwegian fish trade. Retrieved January 14, 2026, from https://www.fao.org/4/a0012e/a0012e09.htm

- Hites, R. A., Foran, J. A., Carpenter, D. O., Hamilton, M. C., Knuth, B. A., & Schwager, S. J. (2004). Global Assessment of Organic Contaminants in Farmed Salmon. Science. https://doi.org/3030226

- Jillian P. Fry, Nicholas A. Mailloux, David C. Love, Michael C. Milli, and Ling Cao (6 February 2018). “Feed Conversion Efficiency in Aquaculture: Do We Measure It Correctly?” Environmental Research Letters 13, no. 2: 024017.

- Longo, S. B., Clark, B., York, R., & Jorgenson, A. K. (2019). Aquaculture and the displacement of fisheries captures. Conservation Biology, 33(4), 832–841. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13295

- Longo, S. B., & York, R. (2024). Why aquaculture may not conserve wild fish. Science Advances. https://doi.org/ado3269

- Miller, David. “Spinning Farmed Salmon.” Thinker, Faker, Spinner, Spy: Corporate PR and the Assault on Democracy, edited by WILLIAM DINAN and DAVID MILLER, 1st ed., Pluto Press, 2007, pp. 67–93. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt18fs9bh.9. Accessed 14 Jan. 2026.

- National Fisheries Institute (n.d.). Top 10 Lists for Seafood Consumption

- Norwegian Seafood Council (16 June 2025). Norwegian salmon continues to lead global sushi category 40 years on from its introduction to Japan

- World Bank (24 June 2025). Harnessing the Waters: Sustainable Aquaculture

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)