Fish farming's hidden truth: How aquaculture actually intensifies overfishing of wild species

Coral Red: Mostly False

Orange: Misleading

Yellow: Mostly True

Green: True

Learn more about our fact-checking policies

Fish farming's broken promise: The industry that intensifies overfishing

The aquaculture industry has long marketed itself as the solution to overfishing, promising to relieve pressure on wild fish populations while feeding a growing world. This narrative helped propel fish farming into a $300 billion global industry that now produces more fish than wild-capture fisheries. Behind the eco-friendly marketing, however, lies a troubling reality: industrial fish farming actually exacerbates overfishing by consuming massive quantities of wild fish to produce feed for farmed species.

The feed paradox

At the heart of aquaculture's sustainability crisis is an uncomfortable truth about fish feed production. The most popular farmed species in wealthy nations, particularly salmon and trout, are carnivorous fish that require diets made from wild-caught species. These small coastal fish, including sardines, anchoveta, herring, and menhaden, are caught from so-called reduction fisheries and processed into fishmeal and fish oil (FMFO).

Reduction fisheries now account for roughly 25% of the global ocean catch, with the vast majority of resulting FMFO used to feed farmed fish. Rather than decoupling fish production from wild capture, the industry has created a protein drain, consuming more wild fish than it produces in edible farmed product.

"The aquaculture industry has sold people the narrative that it is a silver-bullet solution for overfishing. Instead, it's the opposite: fish farming depends on massive amounts of wild-caught fish for feed and is devastating the oceans. Alongside the industry's rise, UN data show that global fisheries have become even more depleted." - Laura Lee Cascada, Director of the Aquaculture Accountability Project

Global south communities bear the cost

The extraction of forage fish disproportionately impacts vulnerable communities in the Global South, where these coastal species have historically provided sustenance. A 2019 Greenpeace investigation mapped dozens of fishmeal factories across West Africa, primarily in Mauritania, Senegal, and The Gambia, that process wild fish into FMFO for export to the European Union, China, and Vietnam. Scientists now consider these fisheries overexploited, yet exports continue to grow amid inadequate reporting and enforcement.

In South America, Peru's anchoveta fishery, the world's largest source of FMFO, has faced repeated early closures or season cancellations over the past four years due to low biomass and high juvenile catch rates. These emergency measures reflect the intense fishing pressure driving stock depletion. A 2024 report by Feedback Global (now Foodrise) revealed that Norway's salmon industry alone extracts almost 2 million tonnes of fish for feed annually, much of it from Northwest Africa, putting nearly 4 million people at risk of undernourishment.

The efficiency myth

Norway-based Mowi, the world's largest salmon producer, exemplifies the industry's net protein loss. In 2019, Mowi sourced nearly twice as much wild fish as the amount of salmon it harvested. Specifically, the company used approximately 880,000 tonnes of wild fish to produce 436,000 tonnes of salmon. This capture volume exceeds the entire volume of wild fish caught by Canada in 2018.

According to Mowi CEO Ivan Vindheim, "Food security and climate change are two of the most pressing challenges facing humanity. As a seafood producer, Mowi is unlocking the potential of the ocean to produce healthy and climate-friendly food for a growing world population." The company's own production figures tell a different story, one of resource extraction rather than ocean conservation.

Misleading metrics obscure the truth

The aquaculture industry has promoted two key metrics to reassure policymakers and consumers:

Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) and the Fish In/Fish Out (FIFO) ratio. Both measures, however, are deeply flawed tools that conceal the industry's continued depletion of wild fish populations.

MSY emerged in the 1940s not from ecological science but from political and commercial ambitions to maximize harvests. The model defines sustainability as maintaining fish populations at roughly half their natural abundance, intentionally keeping stocks in a depleted state. Several fisheries management agencies have pushed this threshold even lower, allowing some fisheries to be considered sustainable with populations reduced by as much as 70% from their original size.

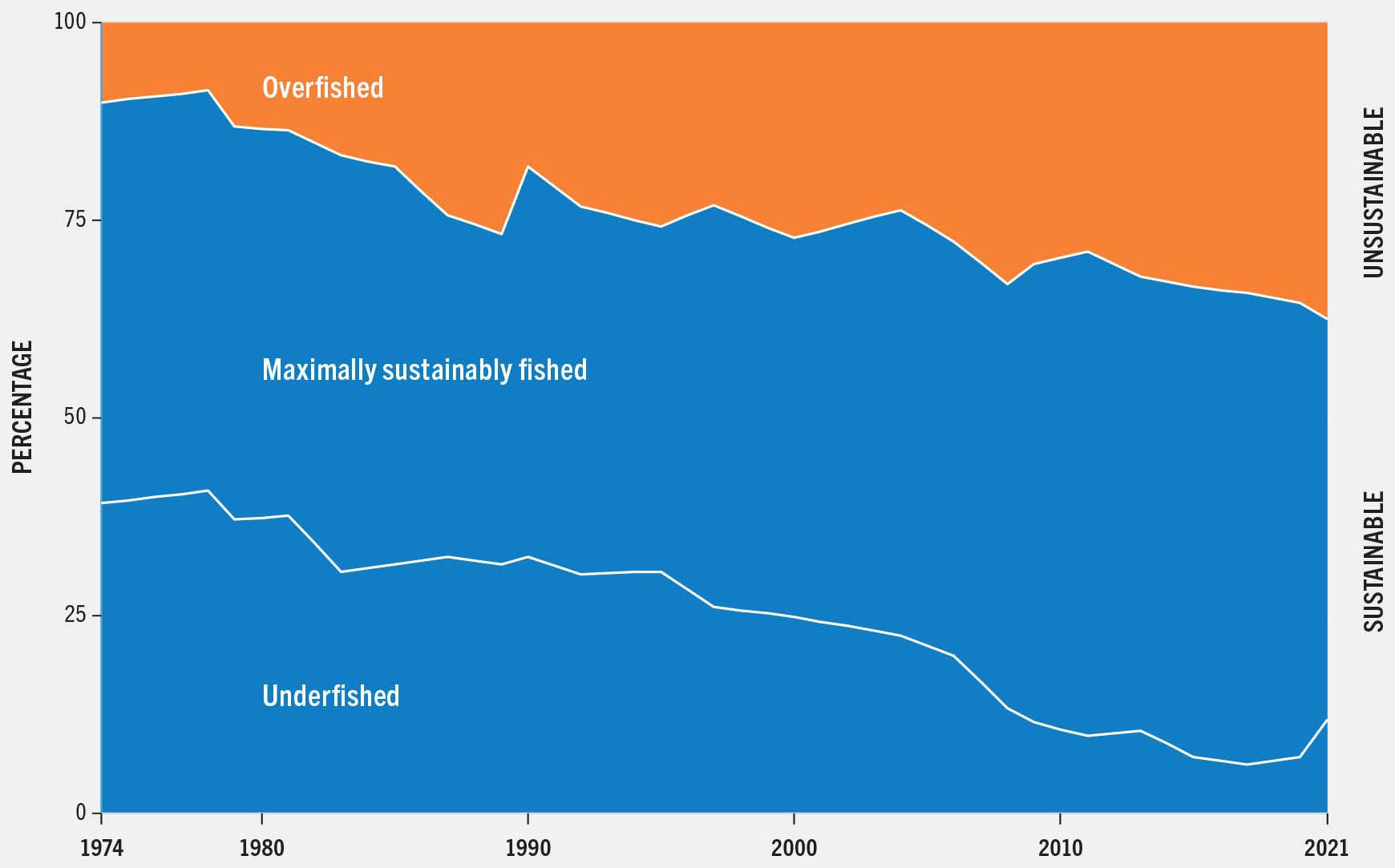

If aquaculture were truly relieving pressure on wild fisheries, MSY indicators would show broad recovery. Instead, the opposite has occurred. In 1980, roughly 34% of assessed stocks were underfished, about 56% were fully exploited, and around 10% were overfished. Today, those proportions have inverted; only about 7% of global stocks remain underfished, roughly 35% are overfished, and the majority fall into the fully exploited category.

The FIFO ratio presents an equally misleading picture. Developed by the International Fishmeal and Fish Oil Organisation (IFFO), a global trade group for the FMFO industry, FIFO measures the kilograms of wild fish required to produce one kilogram of farmed fish. The industry has reported steadily shrinking FIFO ratios, reaching a low of 0.27 in 2020, often cited as proof that aquaculture is becoming more efficient.

A groundbreaking 2024 study published in Science Advances challenges this narrative. Researchers recalculated FIFO ratios for the top 11 fed aquaculture species using comprehensive accounting methods and found that true ratios were 27 to 307% higher than industry estimates. For carnivorous species like salmon, the findings were particularly stark; wild-fish inputs exceeded twice the farmed biomass produced, with aggregate ratios ranging from 2.27 to 4.97. For salmon specifically, the number reached up to 5.57, revealing that farmed salmon may consume nearly six times their weight in wild fish before harvest.

Ecosystem consequences

The ecological impacts extend far beyond depleted fish populations. Small coastal species sit near the bottom of the marine food chain, playing a critical role in transferring energy from plankton to higher-level predators like sharks. Intensive harvesting of anchovies, sardines, and similar species for FMFO has been linked to declines in seabird populations that rely on these fish for feeding chicks.

Exploitation of the Benguela sardine for FMFO in southern Africa has contributed to the endangered status of African penguins and Cape cormorants. These cascading effects demonstrate how industrial aquaculture's appetite for forage fish disrupts entire marine ecosystems while marketing itself as ocean-friendly.

The promise that fish farming would save wild fisheries has proven to be exactly what critics warned: a carefully constructed myth that allows an extractive industry to expand unchecked. Fish, both carnivorous and herbivorous, have a large and negative impact on our planet due to their huge resource footprint. Just as with land animal production, inefficiency is baked into fish farming. As carnivorous species dominate aquaculture production, and reduction fisheries supply their feed, the industry remains a net consumer of ocean protein rather than a solution to overfishing.

Stand Against Nutrition Misinformation

Misinformation is a growing threat to our health and planet. At foodfacts.org, we're dedicated to exposing the truth behind misleading food narratives. But we can't do it without your support.

foodfacts.org is an independent non-profit fact-checking platform dedicated to exposing misinformation in the food industry. We provide transparent, science-based insights on nutrition, health, and environmental impacts, empowering consumers to make informed choices for a healthier society and planet.

Was this article helpful?

.svg)