Dr. Paul Saladino suggests "Olive oil is not for cooking and should not be heated."

Final Take Away

Absolute claims stating that a food is either good or bad tend to overlook the bigger picture, made up of all of the evidence available, as well as other important factors such as the context in which that food is being used, or an individual’s health profile and dietary sensitivities. While olive oil is not a necessary component of a healthy diet, the decision to incorporate olive oil, whether as a dressing or to cook with, should be evidence-based.

We have contacted Paul Saladino for comments and are awaiting a response.

Olive oil, particularly Extra Virgin Olive Oil, has numerous health benefits, which are not fully explored in Saladino’s video. These benefits are largely attributed to its high content of monounsaturated fats (especially oleic acid) and various bioactive compounds, including polyphenols and antioxidants. When olive oil is heated, it loses some (but not all) of these benefits—for instance, its polyphenol content decreases. Yet, cooking with olive oil can also enhance the nutritional value of the food it's used to prepare.

One of the most significant studies on olive oil is the PREDIMED (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea) trial, which was conducted in Spain. Participants were at high cardiovascular risk, but had no cardiovascular disease at enrollment. It found that individuals on a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra virgin olive oil had a 30% lower risk of cardiovascular events compared to those on a low-fat diet. This large-scale, randomized trial provided further good evidence for the heart health benefits of olive oil. Meta-analyses have also “found that regular consumption of olive oil –as the main added fat in the context of a healthy diet– was inversely associated with all-cause mortality, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.” (Martinez-Gonzalez et al., 2022)

Evidence quoted: A report published in the Journal of Foodservice is cited to support the claim that olive oil should not be heated, highlighting the following quote: “heat degrades polyunsaturated fatty acids into toxic compounds.”

Verification: The next sentence in the same paper notes that on the other hand, “saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids are resistant to heat-induced degradation.”

Let’s take a closer look at the composition of olive oil:

Saturated fat: 14%

Monounsaturated fat (MUFA): 73%

Polyunsaturated fat (PUFA): 11%

In other words, olive oil is mainly made up of fats that are relatively heat-resistant, as noted in the same paper cited by Saladino. In fact, when asked which oil would be best to cook with, the lead author of that same paper, Professor Martin Grootveld, recommended olive oil.

Olive Oil (particularly Extra Virgin Olive Oil) is generally considered safe to cook with, for two main reasons:

- Oxidative stability: Oxidation refers to a chemical reaction that occurs when oils are exposed to heat, light, or air, potentially leading to the formation of harmful compounds. However, olive oil is relatively stable when heated because it contains high levels of monounsaturated fats, which are more resistant to oxidation than polyunsaturated fats, and due to the presence of antioxidants (source)

According to recent research, “EVOO [Extra Virgin Olive Oil] has a good PUFA:MUFA balance, which confers it stability properties against oxidative thermal degradation, particularly regarding the formation of volatile aldehydes, so EVOO is a proper and recommendable oil to use in food frying.”

- Smoke Point: The smoke point is the temperature at which an oil begins to smoke and break down. For extra virgin olive oil, this is typically around 190–210°C (375–410°F), which is higher than many common cooking temperatures, such as sautéing or baking. Regular olive oil has a slightly higher smoke point.

Just a few weeks after making the claim that you should not cook with Olive Oil, Paul Saladino released a new video reinforcing his position. In this new post, he argues that going by an oil’s smoke point is misleading, and that you should go by the peroxidation index to choose an oil that is safe to cook with. Kathleen Benson, Registered Dietician at Top Nutrition Coaching, clarified this matter for us:

What does this mean for the consumer?

Extra virgin olive oil holds up well for cooking and keeps many of its helpful compounds, even when heated, as long as it stays under its smoke point. There isn't strong evidence comparing peroxidation to smoke point as a better safety indicator, but olive oil is still considered a healthy option. Peroxidation occurs when oil is exposed to excess air, light, or heat over time, leading to rancidity. You can tell if oil has undergone peroxidation (one way of going rancid) by noticing an off-smell and unpleasant taste.

Incorporating olive oil into your cooking enhances flavour and supports heart health and overall well-being. It is safe to use as a cooking oil, providing the right balance of flavour and nutrition.

Olive Oil, Extra Virgin Olive Oil, Light Olive Oil… which should I choose and when?

“Monounsaturated oils such as olive oil, avocado oil, and peanut oil are a good choice from a health point of view because they contain healthy fats. Olive oil can be used in an air fryer because it remains stable at high temperatures, with a fairly high smoking point. There are many types of olive oils available on the market, labelled as “light olive oil”, “pure olive oil”, “extra light olive oil”, and just “olive oil”, which have high smoke points, but are heavily refined, meaning they lose the nutritional compounds that extra virgin olive oil has. If you are cooking at less than 200C (392F) in the oven or air fryer, then extra virgin olive oil is the best option as it contains the healthy polyphenol compounds lost through processing. For temperatures over 200C (392F), avocado oil is a good option because it has a higher smoke point than extra virgin olive oil.” (The Science of Plant-Based Nutrition p. 155)

Be skeptical of absolute statements, especially when they're not supported by evidence of impact on humans.

In a video published on Instagram on August 18th, 2024, Dr. Paul Saladino discusses potential issues related to the consumption of olive oil. While he suggests that (good quality) olive oil is a better choice than seed oils for uses in salads or dressings, he also states that it should not be heated, and advises against cooking with olive oil due to oxidation. Let’s take a closer look at the basis of this recommendation and fact-check the claim that olive oil should not be heated or cooked with.

Heating olive oil can reduce some of its beneficial properties; however, it remains a healthy cooking option as long as it's not heated beyond its smoke point.

Olive oil is a staple in many kitchens worldwide, and a primary source of fat in the Mediterranean diet, which is broadly acknowledged as a healthy eating pattern to protect against cardiovascular disease. Claims that olive oil is not as healthy as you might think can easily leave readers confused and overwhelmed. Let’s dig deeper into the science behind this popular cooking oil, and move beyond statements isolating single ingredients.

Can your body really replace carbs with protein? Examining the claim that 70% of protein turns to glucose

Claim 2: “You do have cells in your body that need glucose. Your red blood cells, your inner medulla, your kidney, your brain, and your ovaries will require glucose. So you do need some glucose, but 70% of the meat you eat breaks down to glucose.”

Fact-check

It’s true that certain cells in the body, such as the red blood cells, require glucose for energy. However, the claim that 70% of dietary protein from meat converts to glucose is not accurate, and significantly exaggerated. The process of gluconeogenesis, where protein is converted to glucose, does occur, but at much lower rates than suggested.

For example, in one study where participants consumed 50 grams of protein from cottage cheese, only 9.7 grams of glucose were produced, equating to a 19% conversion rate. Much lower than the 70% being claimed.

Another study used whole eggs as the protein source in a similar experiment. The researchers found that out of 23 grams of protein consumed, only 4 grams of glucose produced were from the protein consumed. This is an even lower conversation rate of 8%, far from the 70% conversion rate claimed.

Conclusion

While Candi Frazier's claims about carbohydrates and protein conversion to glucose contain elements of truth, they are often exaggerated or misleading. Carbohydrates, while not essential for life, offer significant health benefits and play a crucial role in our diet. It is important to approach nutrition with a balanced perspective, recognising the value of all macronutrients in maintaining optimal health.

Candi Frazier, also known as The Primal Bod on Instagram, recently made several claims in a reel about how our bodies use carbohydrates, glucose, and fat for energy. She claimed that carbohydrates are not essential, that a significant portion of protein (70%) is converted to glucose, and that fats should be the primary fuel source.

Claim 1: "Carbohydrates are not essential"

Fact-check

While it's true that carbohydrates are not strictly essential for sustaining life, that doesn’t mean they don’t have significant benefits for our health. For example, carbohydrates are a primary energy source, especially for high-intensity activities. Research has shown that consuming carbohydrates before or during physical activity can enhance both resistance training and endurance performance. Conversely, very low carbohydrate or ketogenic diets may impair performance.

Beyond the benefits to athletic performance, high carbohydrate foods that are rich in fibre, such as whole grains and fruits, are consistently associated with better long-term health outcomes. These include lower risks of mortality, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes.

In contrast, some low or no carb foods like red meat, may increase health risks.

It’s also important to consider what foods you are replacing. Replacing 5% of calories from saturated fats (found in foods like meat and butter) with carbohydrates can lower the risk of total mortality by about 8%. This means an 8% lower risk of dying during the course of the included studies that produced this result. Similarly, replacing 5% of calories from saturated fats with slow-digesting carbohydrates (predominantly from fiber-rich foods) can reduce the risk of coronary heart disease by 6%.

Replacing animal protein with carbohydrates has shown similar health benefits, which contradicts the claims made in Candi’s video. High-carb foods, particularly those high in fibre, are generally healthier than many low or no-carb foods like red meat.

Carbs get consistently demonised by the media, despite having many health benefits. In this article, we fact-check some of these claims with the help of Dr. Matthew Nagra, providing a clearer understanding of the science, so you have more confidence in what you eat.

On June 6th, 2024, Candi Frazier aka theprimalbod published an instagram reel claiming "70% of the meat you eat breaks down to glucose" to explain why carbohydrates are not essential and how we can get all our energy from fats and protein.

We evaluate the claim that 70% of protein breaks down to glucose, and whether carbohydrates are necessary in the diet.

Claims that 70% of protein converts to glucose are highly exaggerated; actual conversion rates are much lower, around 8-19%. Replacing saturated fats with carbohydrates can reduce health risks, highlighting the importance of a balanced diet.

With keto and carnivore diets becoming more popular, are you wondering if you can ditch carbs altogether? Read on for why a balanced diet still matters for your health and energy.

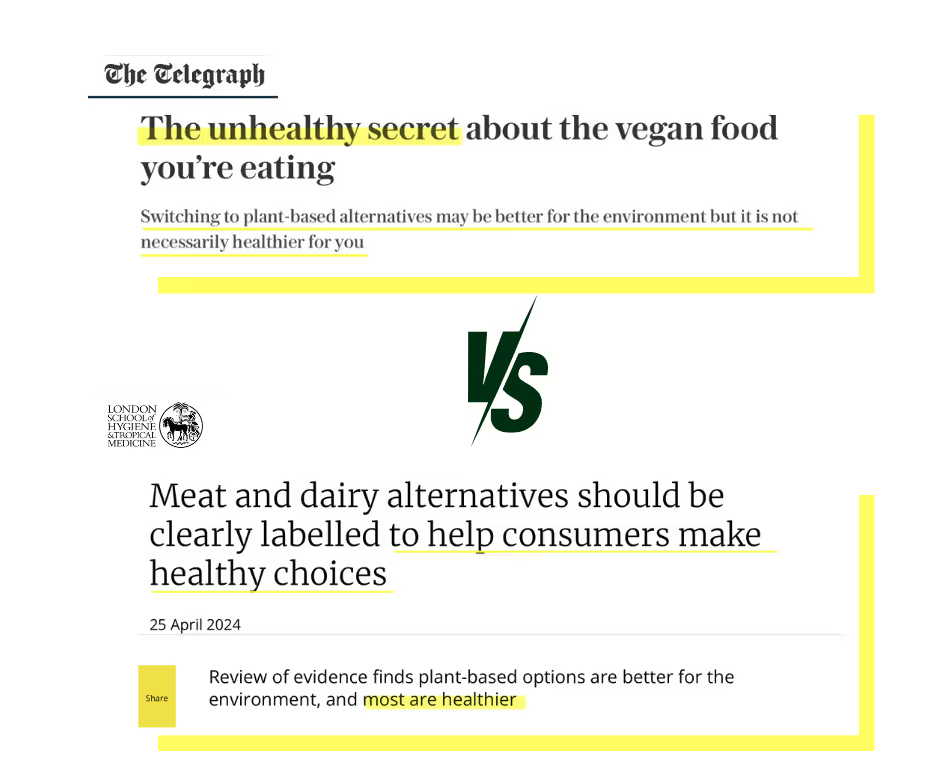

Beyond Headlines: Fact-checking The Telegraph’s claims on the health effects of plant-based alternatives

What is the Ultra-Processed Debate surrounding Plant-Based alternatives about?

The main reason why NPBFs tend to be portrayed as “not necessarily healthier for you” is because they fall within the broad category of Ultra-Processed Foods (UPFs). However, this latest systematic review points to the need for nuance, as all plant-based alternatives are not created equal.

- What is the problem with Ultra-Processed Foods?

“Ultra-processed foods have been associated with many diet-related diseases because these foods are generally energy dense and hyper-palatable.” The study’s authors note that although all NPBFs technically fall within the category of UPFs, not all of them are energy-dense or hyper-palatable. In fact,

“The nutritional composition of some NPBFs aligns well with healthy dietary recommendations, such as having a high fibre content, low energy density, and low saturated fat content.”

Another recurring concern when comparing NPBFs and their Animal-Based (AB) counterparts is their high sodium content. However, similar sodium levels were generally observed between NPBFs and their AB counterparts in the aforementioned study.

Concerns can arise in the case of over-consumption of plant-based substitutes. This cautious approach reinforces the authors’ conclusion that these substitutes should be viewed as stepping stones to a more sustainable, healthier diet, focusing on plant-based whole foods as the bulk of one’s diet.

- What should we look out for when buying plant-based alternatives?

The study highlights the need to look out for options which offer a high fibre content, low energy density and low saturated fat content. When those criteria are met, they conclude:

“From the limited evidence on health, the inclusion of NPBFs into diets appears to typically have beneficial health effects, particularly the consumption of PB meat alternatives. The positive health effects mostly relate to better weight management and associated reduced risk of noncommunicable diseases in high-income (and often obesogenic) countries.”

Final Take Away

Let’s revisit the initial claim that a switch from animal-based products to plant-based alternatives was not necessarily healthier. The study’s authors note that a complete switch is rarely observed, as new evidence suggests that “people who consume NPBFs also tend to purchase ABFs.” They therefore warn against the tendency to push a narrative which defends the superiority of one product against the other:

“Instead of continuing the debate between the superiority of ABFs vs NPBFs, or vice versa, acknowledging and embracing their complementary differences can contribute to a less polarised dietary transition.”

Clearer labelling of plant-based alternatives could therefore favour not only better informed choices, but also encourage a more realistic transition towards plant-centred diets, which a stark opposition between NPBFs and ABFs might make harder.

We have reached out to The Telegraph and the study's lead author for comments and are waiting for their responses. This fact-check will be updated with any comments or clarifications we receive.

CLAIM 2: But they (PB alternatives) are “not necessarily healthier for you.”

FACT-CHECK: The Telegraph’s coverage differs from the study’s conclusions. While whole plant foods remain “the gold standard,” according to first author Sarah Najera Espinosa, the study focuses on the positive role of NPBFs as stepping stones towards achieving not only more sustainable but also possibly healthier diets.

The nutritional value of the NPBF products available varies greatly, hence the suggestion for clearer labelling to help consumers make informed choices. Plant-based alternatives currently all fall within the broad ‘ultra-processed’ category, which tends to be considered by consumers as unhealthy. A subdivision of these products would help distinguish between less health-promoting products and those which offer greater nutritional value. This clarification is mentioned in The Telegraph’s article. However, the article’s introduction directly attributes the suggestion for clear labelling to the public’s lack of awareness regarding the ultra-processed nature of plant-based alternatives, echoing The Independent’s choice of headline: “Calls for plant-based alternatives to be labelled with warning signs.” Such headlines do not reflect the findings of the study which both outlets are reporting on.

The Telegraph’s eye-catching headlines were based on their report of a recently published study conducted by researchers from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the University of Leeds. The study systematically reviewed fifty-seven peer-reviewed journal articles and thirty-six grey literature sources, published in 2016–2022, and which “contained data on the nutrient composition, health impacts, and environmental impacts of Novel Plant-Based Foods (NPBFs).”

The University’s press release summarised the findings as follows, “Review of evidence finds plant-based options are better for the environment, and most are healthier,” concluding that clearer labelling would be beneficial. The University’s conclusions contrast with The Telegraph’s reporting on the study, which appears to emphasise an unhealthy stigma around plant-based alternatives. To get the full picture, let’s fact-check the above claim step by step:

CLAIM 1: Plant-Based (PB) alternatives may be “better for the environment.”

FACT-CHECK: The study did observe that typically, most plant-based alternatives have much lower environmental impacts compared with their animal counterparts. This is especially clear for Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHGE), but also for Land Use (LU) and Water Footprint (WF). The study’s authors also noted that caution should be exerted not to over-interpret “exact numerical results”:

“Environmental impact calculations are notoriously context dependent and sensitive to methodological and data choices. This makes it impossible to come up with a summary figure that is representative for all products, produced in all countries.”

What they found, however, was that the general direction of the evidence was consistent, highlighting a “broad body of evidence demonstrating a reduction in GHGE, LU, and WF for a wide range of PB products in a wide variety of contexts compared with their ABF [Animal-Based Food] equivalents.”

Be skeptical of absolute statements. When a sensational headline is reporting on recent study findings, look for the University's press release, which will most likely be more balanced.

On April 25th, 2024, The Telegraph published an article entitled “The unhealthy secret about the vegan food you’re eating.” The subheadline adds: “Switching to Plant-Based Alternatives may be better for the environment, but it is not necessarily healthier for you.”

Our analysis aims to evaluate the claim made in the subheadline against the evidence provided in the article and broader scientific evidence.

The study concluded that clearer labeling was recommended to help consumers make healthy choices. However, the study’s conclusions did not support warning signs to raise awareness of the ultra-processed nature of Novel Plant-Based Foods (NPBFs). Rather, it suggested a subdivision of NPBFs, as some offer better nutritional value than others. This could support a shift towards more sustainable AND healthy diets.

Interpreting nutrition research is a complex matter. Sensational headlines might not only distort the interpretation of study findings, they can also impact our understanding of the scientific process and how nutrition works. While we might be left with the impression that a single study has finally uncovered THE secret about a food type or nutrient, it is the totality and the balance of the evidence which informs nutritional guidelines. Read on to get the full picture.

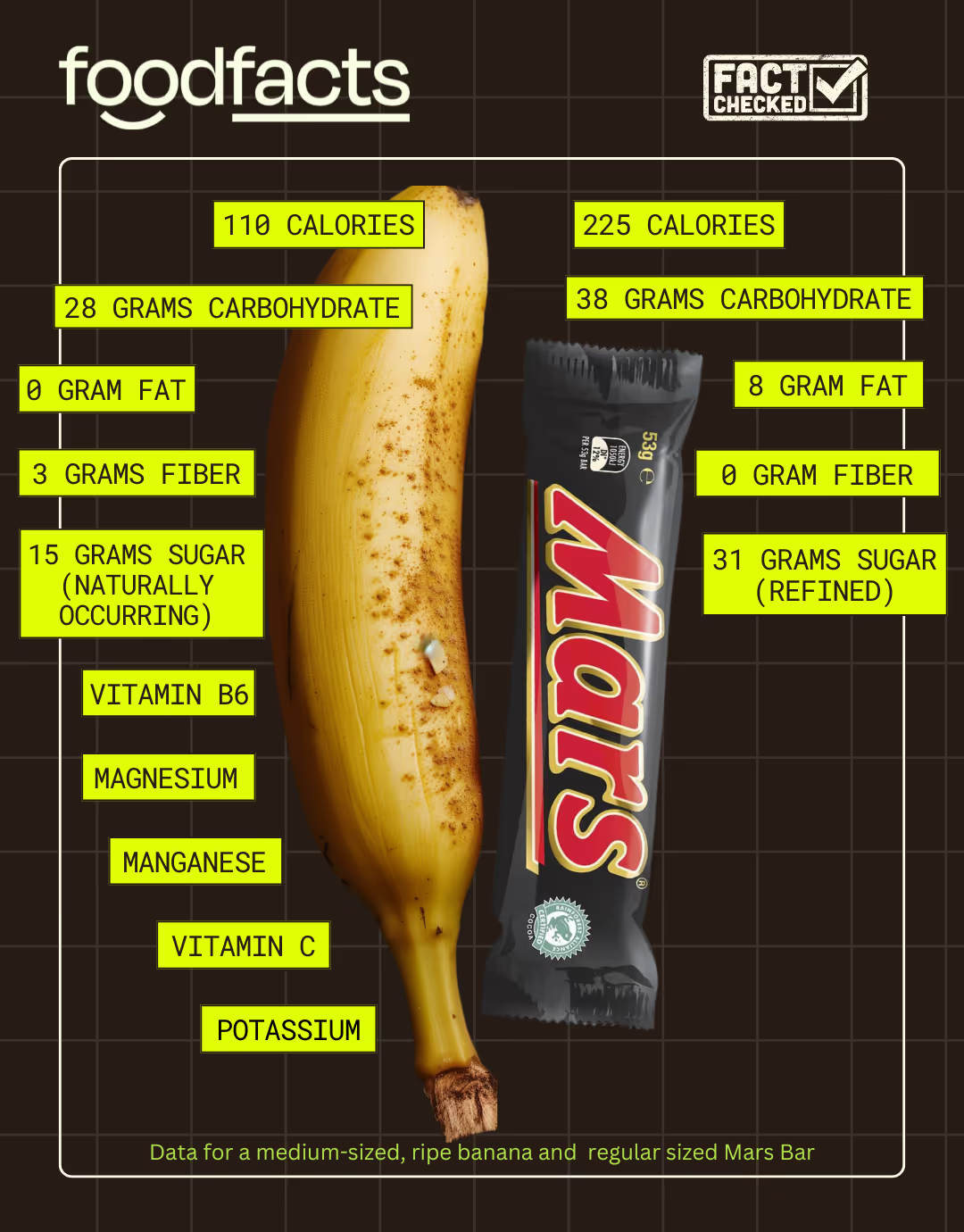

Bananas vs. Mars bars: an unnecessary comparison

Our Final Analysis and Review

Fear-inducing headlines which compare natural fruits with sugary treats have the potential to create confusion, particularly for readers who might not go on to reach the article’s more balanced conclusions. The persuasive power of this metaphor lies in its potential to reinforce growing feelings of distrust when it comes to nutritional and health recommendations. The idea that even “the humble banana” might be disguised as a contributing factor to obesity directly appeals to general fears around food, and feelings of overwhelm which are exacerbated by some social influencers.

The comparison between bananas and Mars bars highlights a broader issue in nutritional information dissemination. While it's essential to be aware of what we consume, context matters. One tip that is often shared by nutrition experts when evaluating whether a food is ‘healthy’ or not is to ask the question: compared with what? Compared with other fruits, this conversation around bananas might have been slightly different. Compared with Mars bars, the picture is rather simple: bananas are the healthier choice.

Misleading ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Factual ⭐️⭐️⭐️

Balance ⭐️

Clarity ⭐️⭐

For more information on how this star-rating system works, you can check out our fact-checking policies here. It can be difficult to discern misleading information, especially when the content of an article appears to be mostly factual. The above star review highlights that balance is an important factor to take into account, besides the source of the information presented. In this case, the lack of balance leads the misleading rating.

Let's dig deeper and take a close look at the different elements surrounding the Mars bar metaphor:

1) The headline

While we might think of metaphors as fanciful or fun uses of language, research shows that they can significantly impact reasoning. Talking about bananas as “Mars Bars in yellow skins” is a sure way to get a reader’s attention. But could it lead to further, noteworthy consequences? The metaphor highlights bananas’ sugar content, while overlooking their numerous health benefits and positive contribution to a balanced diet. Mars Bars, on the other hand, are predominantly made of sugar and fat, provide little nutritional value and are considered a treat rather than a diet staple. Although the article does detail bananas’ many benefits, drawing the comparison with Mars Bars is in itself misleading.

This study of bananas’ ‘pros and cons’ did not stem from observations or concerns from medical or nutrition experts: it was raised by an anonymous reader. While this does not mean that it has no validity, it could lead to unnecessary and unsubstantiated fears regarding the consumption of bananas, which tend to be an accessible, practical and popular fruit option, particularly among children.

2) The analysis: Banana’s pros and cons

Establishing a list of pros and cons can provide balance and nuance to a conversation. In this instance, the list provided by The Telegraph gives rise to an uneven comparison.

The ‘pros’ describe many of bananas’ properties and positive effects on overall health, and are aimed at the general population. On the other hand, the ‘cons’ mainly concern those with specific conditions, and for who the consumption of potassium should be regulated (bananas are widely recognized for their potassium content, which can help control blood pressure).

Besides sharing nutritional facts about bananas and advice about when to eat them (as their nutritional content changes as they ripen, affecting sugar and fibre levels), the article also makes some generalisations which allude to associations between the excessive consumption of bananas and weight gain, for example: “Too many will make you fat.” But this statement lacks context: unless you eat a copious amount, then consuming bananas will not lead to weight gain or obesity. In fact it could be the opposite, as several studies have found an association between fruit intake and weight loss due to their high fibre and water content (source).

3) The conclusions

The conclusions of the article closely align with common sense and general nutritional recommendations, in a stark contrast with the headline’s sensational tone. The bottom line is that it really is an “individual matter”. According to Penny Weston,“Like any other food, you have to listen to your body and how it responds. If you personally find that eating them seems to disagree with you, or your digestive system, look at other ways to get the nutritional benefits they do clearly have.”

This is an important reminder to go beyond headlines: zoom out and look at the full picture.

🚩“THE TRUTH ABOUT” this one food or product which you thought you could trust: does this sound familiar? The ‘truth’ is complex, nuanced, and crucially when it comes to health and nutrition, it tends to be context-dependent. This type of language can be a clue that a claim or post lacks nuance. Phrases like “health saviour” can be another clue. There is no single food or diet which can act as a guarantee of good health. Promoters of such products should be carefully scrutinized.

On February 26th, The Telegraph published an article asking the following question: what are the pros and cons of making bananas one of your five-a-day? The discussion was prompted by an intriguing comparison between bananas, a natural fruit, and Mars Bars, a processed chocolate bar. This review aims to examine the validity of this comparison and the nutritional claims made in the article, emphasising the importance of context in nutritional debates.

In this article, the misleading rating is driven by the impact of the headline. This is particularly important for publications such as The Telegraph which require a subscription to access the full article. In this case, the conclusions of the article do not reflect the headline’s sensational tone, or its implication that bananas are not as healthy as they seem. While the article itself is mostly factual, it does contain a number of misleading, sensational statements.

Sensational comparisons are a popular way to get readers' attention, but they do not yield comprehensive information. For example, by listing bananas' pros and cons, the article highlights their high potassium content. But you would need to eat eight bananas to reach the recommended amount of daily potassium. Excessive potassium intake should not be a concern when making bananas one of your 5-a-day. Challenging fear-mongering practices is an important step to counteract the effects of misinformation.

Are oats still a healthy breakfast choice? Debunking the latest social media myth

Similarly, Dr. Shireen Kassam, a Lifestyle Medicine Physician, supports the inclusion of oats in the diet for their numerous health benefits.

In summary, the evidence overwhelmingly supports oats as a healthy breakfast choice, even for those with sedentary lifestyles. The health benefits they provide—from regulating blood sugar to supporting heart health—remain intact regardless of activity level.

We reached out to Tonic Health for further comment on these claims but have not yet received a response. Any future statements will be considered in our ongoing coverage of this topic.

The Claim: “If you're gonna have a bottle of porridge in the morning and then sit at your desk for eight hours, you're gonna massively spike your blood glucose and then you're not gonna use all that energy from the carbs. Not a good breakfast if you're sitting in an office all day.”

The Facts:

Oats are widely recognised as a health-promoting food, rich in protein, fibre, and bioactive compounds. While it's true that consuming oats can cause a rise in blood sugar levels, this is a normal physiological response. For healthy adults without conditions such as diabetes, this is not something to avoid.

Moreover, oats have numerous health benefits. They contain beta-glucan, a type of soluble fiber that is responsible for much of the health benefits of oats:

- Regulate Blood Sugar: By slowing the emptying of the stomach and absorption of glucose into the blood, beta-glucan helps stabilise blood sugar levels.

- Promote Satiety: Oats can help you feel fuller for longer, which can be particularly beneficial if you're spending long hours at a desk.

- Support Cholesterol Levels: Regular consumption of oats is linked to lower levels of bad cholesterol (LDL).

- Boost Heart Health: The anti-cholesterol effects of oats contribute to overall cardiovascular health.

- Enhance Immune Function: Beta-glucan may also support a healthy immune system.

Scientific studies back these benefits, indicating that oats can play a beneficial role in a balanced diet regardless of physical activity levels. The claims made by Sunna van Kampen lack this robust scientific backing.

I wish more people would discover the health benefits of having a delicious bowl of oats for breakfast. Medical studies have shown that regular oat consumption is linked to healthy weight loss, lower blood pressure, a healthier gut microbiome, and a reduced risk of heart disease.

Look for evidence: Reliable claims should be backed by scientific studies or data.

On 21st April 2024 via Instagram, Sunna van Kampen made claims that oats are not a healthy breakfast if you sit at a desk all day, saying "you're gonna massively spike your blood glucose and then you're not gonna use all that energy from the carbs. Not a good breakfast if you're sitting in an office all day." We examine this claim below.

Contrary to recent social media claims, oats remain a highly nutritious breakfast option. They help regulate blood sugar, support heart health, and keep you feeling full longer. Scientific evidence supports the health benefits of oats, including lower cholesterol and a healthier gut microbiome, regardless of activity level.

Paul Saladino M.D says "Champions need meat!"

Let’s take a closer look at how Saladino presents his argument and fact-check his claims:

CLAIM: “I challenge you to find a single athlete in this year’s Olympics who will win a medal who is vegan.”

A quick internet search reveals several examples, among which: vegan cyclist Anna Henderson won a silver medal; fencing athlete Vivian Kong Man-wai won gold; and tennis player Novak Djokovic, who doesn’t like to use the term vegan due to the associated misconceptions, also won gold.

These examples show that it is indeed possible to perform at the highest level on a plant-based diet. In addition, nutritional science is needed to answer questions such as:

How can diet support athletic performance? What adjustments might athletes need to make when transitioning to a plant-based diet?

A recent study reviewed the available evidence related to such questions, to assess whether adopting a plant-based diet could improve, or at least not impair athletic performance. Given that plant-based diets are higher in fibre, leading to better satiety, we might expect energy intake to be of particular concern in the context of athletic performance. However, the researchers (West et al., 2023) found that energy intake did not appear to be compromised, and reached similar conclusions regarding carbohydrate and fat intake. More consideration might be given to the quantity and quality of protein intake, and the authors recommended supplementation of ergogenic compounds (creatine, carnitine, and carnosine) for all athletes, and particularly for plant-based athletes. All in all, the review found that with careful planning, the adoption of a plant-based diet should not impair athletic performance.

CLAIM: “I think most if not all athletes and coaches will tell you [animal foods] are essential for optimal performance.”

This is an example of the Appeal to Authority fallacy, where a claim is implied to be true primarily because an authority figure endorses it (in this case, athletes and coaches). While experts are indeed well-positioned to provide insights in their areas of study, it becomes a fallacy when no supporting evidence is provided for the claim. In this video, Saladino does not present scientific evidence to substantiate his assertion that meat is essential for optimal performance and health. Current nutritional science and the diverse dietary practices among today’s elite athletes suggest that a variety of diets, including plant-based ones, can support optimal athletic performance.

Breakdown of the claim:

A) Meat contains essential nutrients;

B) These essential nutrients are needed for athletes to perform optimally;

C) Therefore meat is essential for optimal performance: champions need meat!

What makes this argument so persuasive is that A and B are true. Meat and other animal foods are nutrient-dense; and adequate nutrition is essential for athletes to meet their energy needs. The jump to the conclusion in C is where the issue is: just because meat contains essential nutrients does not mean that meat is itself, essential, because these nutrients can be obtained from plant sources as well.

“Research has shown that there is no difference in performance between those consuming a plant-based diet and those consuming a diet containing meat and dairy foods. No differences in strength, anaerobic, or aerobic performance have been identified.” (Lambert 2024: 174)

💡 For example, the SWAP MEAT: Athlete study from Stanford University sought out to answer the question: does a plant-based diet affect athletic performance? To do so, they separated participants into various groups, depending on the type of performance analyzed (running or resistance training), and on the allocated diet: omnivorous, plant-based incorporating meat alternatives, and whole food plant-based. The results were that “runners and resistance trainers experienced no significant change in endurance or muscular strength on two predominately plant-based diets compared to an animal meat diet.”

Another study published in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition found similar results, and suggested that a vegan diet “could even be more effective for endurance performance” within the population studied (young healthy lean physically active women) (Boutros et al., 2020). This is because in the submaximal endurance test, where participants were asked to pedal on an exercise bike until voluntary exhaustion, vegans achieved higher values than omnivores, which the authors of the study noted could possibly be explained by a higher carbohydrate intake.

While both studies focused on recreational athletes, the results support the adequacy of plant-based diets to sustain increased energy demands, and contradict the popular belief that plant-based foods cannot provide enough or adequate nutrients to support athletic performance (Boutros et al., 2020).

CLAIM: “I don’t understand how most people reconcile this in their minds (visual of Michael Phelps’ diet, containing animal foods at every meal) that these foods that are so bad for us are the foods that athletes need to perform at the highest levels.”

In other words, if these foods are good enough (or in Saladino’s opinion, essential) for professional athletes, how can they be bad for us?

Most national nutritional guidelines recommend limiting certain animal products, like processed and red meat, because research shows that overconsumption can harm health. The saturated fat in these foods has been linked to higher cholesterol levels and an increased risk of heart disease. While athletes and non-athletes don’t need to completely avoid meat to be healthy, a healthy diet doesn’t require animal products, and consuming too much can raise the risk of heart disease.

It’s also important to understand that sports nutrition is different from public health nutrition. “Sports nutrition is methodical, calculated, and used as a tool to optimize performance” says Rhiannon Lambert (The Science of Plant-Based Nutrition, p. 175). It is very different from the average person's dietary needs. Saladino’s argument overlooks that an athlete’s lifestyle, including how they metabolise saturated fat, differs significantly from the general population’s. Public health recommendations are designed for the general population and are different to the needs of an athlete. Therefore general health and nutritional advice should not be based upon athletes’ dietary needs.

Final Take Away

Current research does not support the claim that animal-based foods, more specifically meat, are necessary for athletes. Studies indicate that both plant-based and animal-based diets can effectively support athletic performance. Regardless of preferences, athletes’ dietary needs should be carefully planned and individualized to support optimal performance and health.

We have contacted Paul Saladino for comments and are awaiting a response.

Look for evidence: Reliable claims should be backed by scientific studies or data.

On 31st of July 2024 via Instagram, Paul Saladino M.D commented on this year’s Olympic Games and the marked increase in plant-based meals offered, saying “champions eat meat.” He continues: “removing meat from your diet ROBS you of many vital nutrients (vitamins, minerals, peptides) needed for optimal performance and health…”

Plant-based diets, when well-planned, can also meet the nutritional needs of athletes and support optimal performance.

There is no single diet that fits everyone’s needs or health profile. This is especially true of professional athletes, whose diets need to be carefully and individually planned to meet specific requirements. To truly understand the nuanced relationship between diet and athletic performance, delve into the evidence—or lack thereof—behind the claim that champions require meat for ultimate success.

Latest fact-checks, guides & opinion pieces

.svg)