Who's really qualified to give nutrition advice online? Here’s what you need to know

Trying to figure out who to trust for nutrition information online or who to go to for advice, can be exhausting. It can also lead to you getting wrong or dangerous health advice.

So, who should you turn to for credible advice? A dietitian? A nutritionist? A self-proclaimed "diet expert"?

These terms can be used interchangeably, but there are key differences in the qualifications, regulation, scope of practice, and legal protections for these professionals. In this guide, we’ll break down the key differences to help you separate fact from fiction and make informed decisions about your health.

We’ve based this information on the advice from organisations including the British Dietetic Association (BDA), the Cleveland Clinic, the Association for Nutrition UK, the American Nutrition Association, and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (US).

Dietitian

(RD/RDN - US, RD - UK)

Dietitians are the only nutrition professionals who are regulated by law, both in the UK and the US. They are legally recognised as healthcare professionals. They “assess, diagnose and treat dietary and nutritional problems at an individual and wider public health level”, according to the BDA. Whether in hospitals, clinics, government, or private practice, dietitians offer evidence-based advice targeted to an individual's specific needs or health conditions.

Education & Training

Before obtaining the title of ‘Registered Dietitian’ you must meet certain education and training requirements.

- US: Dietitians need to earn a master’s degree from an accredited dietetics program as of January 2024. They also need to complete 1,000 hours of supervised practice, pass a national exam, commit to following a code of ethics specific to their profession, and continue professional development through their careers. Some states require Registered Dietitians to be licensed, in which case they will also use the letters LD for Licensed Dietitian.

- UK: Dietitians need at least a bachelor’s degree (BSc) in Dietetics or a science degree with a postgraduate diploma or Master’s degree in dietetics. They are required to undergo supervised clinical practice in NHS settings, where they must show clinical and professional competence. All dietitians in the UK must be registered with the Health & Care Professions Council (HCPC).

Regulation

- US: Dietitians are regulated by the Commission on Dietetic Registration (CDR), the credentialing agency for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. RD and RDN are legally protected titles.

- UK: Dietitians are legally regulated by the HCPC, ensuring they adhere to strict standards and an ethical code. The title of "Dietitian" is protected by law.

Key Takeaway

If you’re looking for professional, medical-grade nutrition advice, a dietitian (RD/RDN in the US, RD in the UK) is your best choice. Their training and credentials ensure that their recommendations are grounded in science and tailored to your health needs.

Nutritionist

(US and UK)

Nutritionists provide advice about healthy eating and nutrition education, and can work in various roles, but their scope of practice is narrower compared to dietitians. They might work in non-clinical roles like public health, education, the food industry, sports nutrition, or research.

While some nutritionists may be highly educated, others may not have formal qualifications, and the title "nutritionist" is not legally protected in either country. Anyone can call themselves a nutritionist and legally give nutrition advice either in person or online. So it’s important to understand the different levels of education that fall under this category.

Education & Training

- US: The term "nutritionist" can be used by anyone, regardless of formal education. However, some nutritionists may hold advanced degrees in nutrition and/or dietetics, such as a B.S. or M.S. in Nutrition. Registered Dietitian Nutritionists (RDNs) are both dietitians and nutritionists, but not all nutritionists are RDNs.

- UK: Similarly in the UK, many people study Nutrition at Bachelor's, Master’s and PhD levels but this is different to studying dietetics. It is less clinical and may often have a focus such as public health nutrition or sports nutrition.

Regulation

- US: The term "nutritionist" is unregulated, anyone can call themselves a “nutritionist” regardless of their training and education. However, those with a Certified Nutrition Specialist® (CNS) credential are more regulated. CNS will have an advanced degree in nutrition (graduate or doctorate) from a fully accredited university plus 1,000 hours of a supervised internship and must pass the exam administered by the Board for Certification of Nutrition Specialists. It is the most widely recognised nutrition certification by federal and state governments.

- UK: The title "nutritionist" is not protected by law in the UK either, meaning anyone can use it without formal registration. However, nutritionists can voluntarily register with the UK Voluntary Register of Nutritionists if they meet the required educational standards, which includes completing an accredited degree in nutrition. Registered Associate Nutritionists (ANutr), have typically graduated with a BSc (Hons) or MSc in nutrition science within the last three years. Registered Nutritionists (RNutr) are seen as more credible as they must have demonstrable experience of degree-level, evidence-based practice in a specialist area of nutrition such as nutrition science or public health. Both have committed to adhere to the AfN Standards of Ethics, Conduct and Performance.

Key Takeaway

The lack of legal regulation means that anyone can call themselves a nutritionist, so check for credentials. Look for Nutritionists who have the credentials CNS (US), ANutr (UK), or RNutr (UK) or hold advanced degrees. In certain areas, their formal training, especially clinical training can be limited compared to dietitians.

Medical Professionals

Other medical professionals, such as doctors and nurses, may also provide nutrition advice as part of their overall healthcare practice. However, they typically receive limited formal training in nutrition during their education. While their advice can be valuable, particularly in managing medical conditions where diet plays a role (e.g., diabetes, heart disease), their expertise in nutrition is generally not as comprehensive as that of a dietitian or registered nutritionist. For in-depth and personalised nutrition advice, especially for complex conditions or dietary changes, it is often best to consult with a dietitian, as they are specifically trained to provide evidence-based nutrition guidance.

Some medical professionals may have taken extra training in nutrition and lifestyle medicine, such as Dr Idz who has a Master's degree in Nutritional Research and Dr Shireen Kassam who is a board-certified lifestyle medicine physician.

Social Media Nutrition and Diet ‘Experts’

The explosion of social media has given rise to many self-proclaimed "diet experts" and influencers. These individuals may have little to no formal training in nutrition, yet they often promote specific diets, supplements, or lifestyle changes. Anyone can call themselves a diet expert or nutrition coach, with or without qualifications.

Others may have a degree in a scientific field, and use this to justify their advice on nutrition and health, but this doesn’t necessarily give them the right expertise to provide accurate advice about nutrition and health. For example, Jessie Inchauspé, the self-proclaimed ‘Glucose Goddess’, claims that controlling blood sugar spikes will solve a range of effects on our health. Jessie makes reference to the fact that she is a biochemist, but that doesn’t qualify her as a health professional or to understand the nuanced links between food, blood sugar spikes, and the effects on health.

Her claims have been debunked by experts like Dr Nicola Guess, a Registered Dietitian and PhD, who focuses her work on type 2 diabetes. One of the claims Jessie made was that glucose spikes cause mitochondrial dysfunction, but using the skills most likely gained during her dietetics training and PhD, Dr Nicola Guess pulls apart this claim and shows that it’s not true.

Influencers such as Candi Frazier aka ‘theprimalbod’ may use titles like "Certified Functional Nutrition Therapy Practitioner," but these qualifications are not as rigorously regulated as those for dietitians or registered nutritionists. These titles can provide her audience with a sense of security in her advice, despite her videos often containing false claims, misrepresenting or misinterpreting the studies she cites.

While some social media influencers may offer helpful tips or share their own experiences, it’s critical to verify their qualifications before following their advice. Relying solely on unqualified individuals can lead to misinformation, which may be harmful to your health.

Can you trust everyone with the right qualifications?

In general, while professionals with dietetics training, a PhD, or a medical degree provide better quality, more accurate advice, they are not immune to spreading misinformation. People such as Paul Saladino MD and Anthony Chaffee MD will frequently cite the fact they are medical professionals while making false claims about ‘toxic’ vegetables, among others.

On the other hand, there are also influencers who provide reliable, researched, and nuanced nutrition and diet advice who don’t have a formal qualification such as Ben Carpenter and Graeme Tomlinson aka The Fitness Chef. A good way to spot this is in both cases, neither Ben nor Graeme make wild or exaggerated claims about foods, instead their advice feels more nuanced and balanced.

Conclusion

When it comes to nutrition advice, credentials matter.

Dietitians are the most qualified and regulated professionals, providing evidence-based recommendations. Registered Nutritionists (RNutr in the UK) also offer reliable advice but with less clinical focus. Nutritional therapists, diet experts, and social media influencers should be approached with caution, especially when dealing with medical conditions. Always check the qualifications of anyone offering nutrition advice and choose professionals who are properly trained and regulated.

How to spot fake nutrition advice on social media: 10 red flags

Social media is flooded with health influencers, but not all advice is created equal. Misinformation about food and nutrition can spread fast, disguised as expert advice. In a sea of content, how can you tell what’s useful, what’s questionable, and what’s downright dangerous?

This guide will help you identify common red flags that nutrition “quacks” use so you can protect yourself from misleading advice and focus on credible, evidence-based information. Let’s dive into the most important traits to watch out for.

How Misinformation Spreads on Social Media

Social media platforms reward viral content—so influencers may prioritize engagement over accuracy. Unfortunately, this environment allows misinformation about health and nutrition to spread easily.

This is why it’s crucial to recognize the red flags of unreliable advice. Here are 10 key signs to help you spot quack nutrition advice.

10 Red Flags of Fake Nutrition Advice

1. Outlandish Promises About Your Health

If someone claims their advice will help you live a disease-free, extended life, proceed with caution. Legitimate health outcomes take time and rarely come with guarantees.

2. Use of Absolutes and Imperatives

Statements like “you must eat this” or “you should never eat that” are usually oversimplified. Real health advice considers individual needs and avoids one-size-fits-all solutions.

3. Fearmongering and Food Villainization

Beware of influencers who create fear around specific foods or food groups, such as “gluten is toxic for everyone.” Balanced diets avoid demonizing entire categories of food.

4. Lack of Transparency about Conflicts of Interest

Influencers often promote products, but credible ones disclose their financial ties. Transparency builds trust, even if the person has brand partnerships.

5. Claims of ‘Truth’ or Hidden Knowledge

Avoid accounts that market their advice as “the only truth” or imply mainstream science is lying to you. Science evolves, and health advice should come with context and nuance.

6. Misuse of Scientific Terms

Phrases like “inflammation” or “insulin spikes” can sound impressive, but if they aren’t explained clearly or used correctly, they are likely meant to confuse rather than inform.

7. Vague References to ‘Toxins’ Without Context

“Toxic” is a buzzword used without specifying harmful doses or providing scientific context. Everything has a safe level—water and oxygen included.

8. Contradictory Messaging Across Platforms

If an influencer contradicts themselves frequently, their advice lacks consistency. Reliable experts are consistent in their messaging, even as new research emerges.

9. Conspiracy Theories and Distrust of Science

Quacks often warn against listening to doctors or health authorities and promote the idea that only they can keep you safe from corporate interests or “Big Pharma.”

10. Grandiose or Aggressive Communication Style

Watch out for aggressive language or exaggerated confidence. Experts tend to communicate calmly, even when addressing complex health concerns.

Why Critical Thinking Matters in Nutrition Advice

It’s easy to get caught up in the promises of influencers, especially when their posts are engaging and persuasive. However, following influencers who dismiss science and promote their own narratives can lead you down a dangerous path.

Use these 10 red flags to filter out unreliable information and focus on sources that provide clear, evidence-based guidance. Your health journey should be built on trustworthy advice, not fads or fear.

Follow Evidence-Based Nutrition Experts

The good news? A growing number of qualified nutritionists and dietitians are active on social media, sharing evidence-based tips in an accessible and enjoyable way. Look for accounts run by registered dietitians, nutritionists with professional credentials, and experts linked to reputable organizations.

What to Do Next: Tips for Staying Safe Online

- Verify Credentials – Check whether the influencer has legitimate qualifications in nutrition or health.

- Cross-Check Claims – Look up the evidence behind any health advice before following it.

- Follow Reputable Sources – Prioritize advice from registered dietitians or organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO).

- Engage Mindfully – Ask questions and remain curious, but don’t let fear or trends drive your decisions.

Conclusion: Trust, but Verify

Navigating the world of nutrition advice on social media can feel overwhelming. However, by applying these critical thinking tools, you can identify trustworthy voices and avoid falling for health scams.

Stay skeptical, seek out evidence-based sources, and build your knowledge with confidence. Your health journey deserves facts—not fads.

Fact-checking the firefighter analogy for cholesterol and heart disease

The firefighter analogy draws on a simple and familiar scenario: firefighters are present at a fire to help, not to cause the damage. This comparison suggests that cholesterol, like firefighters, is only present to “help” and is not the cause of heart disease.

The “real” cause of heart disease is said to lie elsewhere. Ben Azadi has suggested that inflammation is a primary cause of heart disease; Anthony Chaffee has highlighted sugar as a key factor; and Barbara O'Neill has discussed the central role of high-carbohydrate diets in heart disease.

In this article, we will detangle the links between various elements of the debate, which regularly get conflated through use of the firefighter analogy and generally through discussions on cholesterol and heart disease on social media.

What the firefighter analogy gets right ✅, and what gets overlooked ❌

✅ Correlation does not mean causation

The first point made through use of the firefighter analogy is that just because two elements are found together does not mean one causes the other. This is true, and in fact, is often the source of nutrition and health misinformation on social media.

❌ Misrepresenting the evidence

While it’s true that correlation does not imply causation, this argument misrepresents the evidence. Numerous studies have demonstrated a causal link between high levels of LDL-Cholesterol (often called ‘bad cholesterol’) and an increased risk of heart disease. This is because high blood cholesterol can contribute to plaque buildup, which can lead to a narrowing of arteries, decreasing blood flow to the heart.

For example, this Meta analysis included 53 Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs), showing that for each 1mmol/L lowering in LDL-Cholesterol, there was a 15% reduced risk of cardiovascular mortality.

✅ Cholesterol is vital

Let’s clarify what cholesterol is and its role in the body: “Cholesterol is a fat-like, waxy substance that helps your body make cell membranes, many hormones, and vitamin D. The cholesterol in your blood comes from two sources: the foods you eat and your liver. Your liver makes all the cholesterol your body needs.” (Source: John Hopkins Medicine)

How can something our body needs cause heart disease? This is the question that the firefighter analogy draws our attention to, where cholesterol is purely seen as a “band-aid” or a “healer.” But the question is not just about labelling substances as ‘good’ or ‘bad’; it’s also about balance.

❌ Distinguishing between cholesterol and excess cholesterol

Yes, cholesterol is vital. So is inflammation, our body’s response to harmful stimuli. And so is glucose as a source of energy. However, issues arise with excess, in the case of cholesterol, when there is excess cholesterol in the bloodstream, more specifically low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol.

The analogy completely overlooks the issue of excess. And as the liver produces the cholesterol our bodies need, we don’t need to consume high quantities of it. As Dr. Idrees Mughal puts it, “All of these people that preach about how important cholesterol is seem to forget that if cholesterol is high in your blood then it’s not in your cells where it needs to do the job it needs to do.”

✅ Dietary cholesterol has little impact on blood cholesterol

We've already distinguished between dietary cholesterol (found in certain foods), and blood cholesterol (the fatty substance that the blood carries). Research has shown that, contrary to previous recommendations, dietary cholesterol has little impact on blood cholesterol.

That being said, individual responsiveness can vary: “For some people, though, blood cholesterol levels rise and fall very strongly in relation to the amount of cholesterol eaten. For these ‘responders,’ avoiding cholesterol-rich foods can have a substantial effect on blood cholesterol levels.” (Source: Harvard Public School of Health. The Nutrition Source)

So, does this mean that most people can eat high amounts of cholesterol-rich foods, and not worry about it? Unlike what the firefighter analogy suggests, it’s not that simple.

❌ Misrepresenting the relationship between diet and blood cholesterol

The analogy overlooks the role of our overall diet, and how it might impact our blood cholesterol. "The types of fat in the diet help determine the amount of total, HDL, and LDL cholesterol in the bloodstream. The types and amount of carbohydrates in the diet also play a role. Cholesterol in food matters, too, but not nearly as much.” (Source: Harvard School of Public Health, The Nutrition Source)

Saturated fat can often coexist with cholesterol in certain foods. And a diet that is high in saturated fat, has been shown to increase levels of LDL-Cholesterol, increasing the risks of heart disease. Trans fats have also been shown not only to increase LDL- Cholesterol, but also to decrease HDL- Cholesterol, thus increasing the risk of heart disease and stroke. In fact, the detrimental effects of manufactured trans fats have led to their phasing out of the food system.

Crucially, the firefighter analogy and the broader narrative it reinforces overlook the fact that heart disease is multi-factorial. Simplifying the issue to a single cause, or dismissing the role of cholesterol entirely, is misleading. Consider the following two ways of tackling such issues:

🟠 Oversimplifications from the broader narrative surrounding the firefighter analogy

It’s not cholesterol, it’s inflammation.

It’s not cholesterol, it’s high-carbohydrate diets.

It’s not cholesterol, it’s sugar.

Vs.

🟢 Evidence-based, balanced nutritional research

Alan Flanagan on Biolayne: “Enough of single-nutrient demonization. Let’s talk about diet […] Singling out sugar is misconceived. Singling out fat is simplistic. The goal for public health is to address the outstanding problem: dietary energy density in the population.’

Let's finish by taking a closer look at the broader narrative that this analogy and discussion fit into, and at some of the evidence which often gets cited to support it.

Some discussions that downplay cholesterol's role in heart disease reference historical claims of industry influence. Anthony Chaffee, among others, has pointed to research showing that the sugar industry covertly paid off scientists in the 1960s to minimise sugar's role in heart disease while focusing blame on saturated fat. These findings are indeed troubling and illustrate how industry funding can erode trust in nutritional science. However, it remains important not to overextend these findings beyond their actual implications. While the sugar industry's tactics effectively derailed discussions about sugar's true role in disease development, we shouldn't frame the debate on diet and heart disease as a simple "either/or" scenario. Put simply, the fact that sugar's role was minimised doesn't mean we should ignore the evidence on saturated fat.

Conclusion

The tendency to oversimplify complex issues (for example by framing them as simple either/or questions) is prevalent on social media. In particular, overly focusing on single foods or nutrients can lead us to overlook the importance of considering one's overall diet, especially when it comes to decreasing the risks of developing heart disease, which is multifactorial. Spotting these patterns can help us to better navigate the world of online nutritional information.

Disclaimer

This article is intended as general information and is not intended as medical advice. Any health concerns or questions should be directed to health professionals.

Analogies can help us to understand complex issues. But they rarely tell the whole story. Always remember to cross-check facts before making dietary changes.

Claim: Blaming cholesterol for heart disease is like blaming firefighters for a fire because they are present every time you enter a building on fire.

The firefighter analogy (occasionally swapping firefighters for ambulances) has been shared by several health influencers, who have used it as an argument to support the adequacy of various eating habits.

While it correctly highlights that correlation does not imply causation, it oversimplifies the role of cholesterol, which has a well-established causal link to heart disease, and ignores the impact of excess LDL- Cholesterol in the bloodstream.

Analogies can be very persuasive because they allow to explain extremely complex mechanisms through familiar experiences. Analogies can also make us 'tick,' making them very shareable. However, it's crucial to recognise that they can also lead to oversimplifications, misconceptions, or even distort the scientific evidence. Keep reading for a detailed breakdown of the firefighter analogy and its implications: what it gets right, what it gets wrong, and what it overlooks.

Should we compare smoothies and doughnuts?

Final Thoughts

A fallacy often presents itself as a plausible argument, as something which sounds like it should be right. Most of the time, however, it is based on faulty reasoning and isn’t supported by evidence. In this case, Dr. Idz adds that “all carbohydrates are broken down into simple sugars anyway,” highlighting that simplistic comparisons can be quite unhelpful as they can distort one’s understanding of nutrition. That is why spotting these patterns on social media matters. Our food choices directly impact our health, and they should be based upon evidence.

False equivalences are popular on social media, but what are their effects? In the short-term, they tend to cause confusion, even if they are generally oversimplified. Think about a bottle of Innocent Smoothie with a label: no added sugar. And then hearing that that same bottle is worth 19 doughnuts in sugar.

But more importantly, they tend to be unwarranted. Another example might be to compare cats and leopards on the basis that they are both felines. But you would never compare them in a discussion about what pets to get in your house. Unwarranted comparisons don’t just generate clicks and view; they can have long-term effects on how we think about nutrition.

- They can lead to unnecessary guilt

When you start believing that all sugar is bad, you might feel guilty for enjoying a fruit smoothie or a piece of dark chocolate. This turns eating into a stressful experience instead of an enjoyable one. The truth is, no single food makes or breaks your health—what matters most is your overall diet.

2. They Promote an Imbalanced View of Nutrition

When you focus on one food being “bad,” you might start avoiding entire food groups without understanding their full nutritional value. Instead of obsessing over individual foods, it’s more important to focus on balance and variety in your diet. This mindset shift doesn’t only affect psychology. Research has shown that “mindset meaningfully affects physiological responses to food” (Crum et al., 2011). This study showed that levels of what we know as the hunger hormone (grehlin) went down a lot more when participants thought they had consumed an ‘indulgent’ milkshake (high calorie, high fat), than when they thought they had consumed a ‘sensible’ shake (low fat). In other words, how we think about food can have a very real impact on hunger regulation, and on our overall diet.

3. They Might Encourage Restrictive Diets

These oversimplified messages can fuel extreme, restrictive diets. Whether it’s cutting out all fats or avoiding carbs entirely, these trends distort what a healthy diet really looks like and could lead to nutrient deficiencies. Dr Rajan Karan is an NHS surgeon who is passionate about correcting medical misinformation. As reported by The Daily Express, he says on the subject of restrictive diets that he is “not a fan,” because “obsessing over what you eat can become a preoccupation and lead to a cycle of even more restriction, plus stress and anxiety.” Beyond the psychological aspect of restriction, he adds that “by cutting out a whole food group, you’re going to be missing out on crucial nutrients."

We have contacted Tonic Health for comments and are awaiting a response.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for educational and informational purposes only. It reflects the views and analysis of the author based on available evidence at the time of writing. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, readers are advised to consult with healthcare professionals for specific advice related to their dietary needs. This article critiques claims made in publicly available social media content and does not intend to defame or misrepresent any individual or brand. References to external sources are provided for context, and no affiliation or endorsement is implied.

To understand the impact of this misleading comparison, let's examine the questions it gets us to focus on as we process it, and those it overlooks. By identifying these questions, we can better recognise patterns of misleading nutritional information online.

What gets our focus

→ “What foods should I avoid?”

Tonic Health’s comparison is based on sugar content only, and looks at an entire bottle of smoothie, containing over 82g of sugar. The question consumers are led to focus on as they process this comparison is: what foods should I avoid to be healthy? The claim that 19 doughnuts contain as much sugar as that smoothie bottle suggests that we can add green smoothies to the “banned list” (or perhaps to the “list of foods I was wrong about”).

What gets missed out

→ "In what context am I eating this food?"

The doughnut comparison can easily trigger or amplify feelings of guilt related to food. Crucially, it overlooks a very important question which we can ask ourselves when we see claims on social media that a food item is good/bad, healthy or unhealthy: in what context am I eating this food?If we apply it here, it becomes immediately apparent that drinking an entire bottle of smoothie in one sitting is highly unlikely - indeed the label specifies that one bottle contains 5 (150ml) servings. Yet this is exactly what gets compared with the ‘shocking’ amount of 19 doughnuts.

Other questions to add context are: what (am I eating this food) with? This is important, because while a diet that is high in sugar can have negative health consequences, an occasional glass of smoothie (in the context of a healthy diet) paints a different picture. By asking “what am I eating this with?”, the overall diet gets brought to the foreground, rather than single food items. This might seem like common sense, and some might wonder if a single video really warrants this kind of discussion. One video is unlikely to change your mindset. But the point is that as we get increasingly exposed to similar content, these questions can shape our habits and influence our mindset on nutrition. And that can have a lot more impact.

In some cases, asking “what am I eating this food instead of?” can also remind us to use nutritional labels as a tool to compare food items, helping consumers to choose one product over another - but this is implying that the products are in a similar category. The issue here is that smoothies and doughnuts aren’t comparable in a meaningful way.

→ "What does this food add to my diet?"

Smoothies can sometimes help us reach our ‘5-a-day’ target. That being said, guidelines indicate that only 1 serving of smoothie or fruit juice should count towards that target, regardless of how many fruits are in that smoothie. This is because when fruits get blended, natural sugars get released and become “free sugars,” which we are advised to limit. But this doesn’t mean they need to be altogether banned.

This is where the question “what does this food add to my diet?” can be helpful. Yes, fruits and smoothies contain sugar, but what else do they bring to the table? Smoothies can increase intake of dietary fibre, which isn’t affected by blending. The smoothie profiled in Tonic Health’s video also contains vitamins (B1, B2, B3, B6, C and E), as well as anti-oxidants. Doughnuts, on the other hand, have a very different health profile. Beyond their sugar content, they are high in fat and saturated fat, which is recommended to be consumed in limited amounts, and a single doughnut contributes to 10 % of daily energy needs. Let’s not go into how many calories 19 doughnuts would add up to… While doughnuts add little in terms of nutritional value, they can provide contentment. This should not be entirely dismissed, because it is also important to maintain a healthy relationship with food - something which guilt can quickly get in the way of.

We’ve all heard that sugar is bad for us, or phrases like “sugar is sugar.” These statements might sound intuitive, but are they based on scientific evidence? Nutrition advice on social media is often reduced to oversimplified statements like “this is bad” or “this is good.” But when we rely on these black-and-white categorisations and comparisons, we miss the bigger picture of what a healthy diet is, and its impact on overall health. This is particularly true of unwarranted comparisons highlighting sugar content, as they isolate one single element, forgetting the importance of considering one’s diet as a whole.

This is a perfect example of a logical fallacy called a false equivalence. This fallacy occurs when two items or scenarios are presented as being logically equivalent when in fact they aren't comparable in any meaningful way. So it’s comparing apples to oranges.

Every food has its place. There is no bad or perfect food. As a consumer, this is more about understanding the health claims and getting the right information. Consumers need to be aware that when it comes to nutrition and nutritional claims there is a lot of misinformation out there.Determining your health goals will allow you to have more discernment as to the types of foods and beverages that you include in your daily lifestyle. Moderation is the key and your success depends on the sources of nutritional knowledge that you follow.

First, you need to determine the health reason of why you would like to add a green smoothie. Second, think about what you can have with it: I often tell my clients to have a serving of a smoothie with a meal or as part of a snack that has protein and good fat so that the body can efficiently use it as energy. If you have one (smoothie) serving as it’s suggested, then it is about 11 grams of sugar which is equal to having a fruit serving. The tendency of a fruit is to raise blood sugars; to offset a rapid rise, then consuming protein and good fats would be suggested, or as part of a meal.

Look for balance when looking for nutritional advice online. Don’t let extreme claims cloud your judgment; it’s what you eat consistently that defines your health, not that occasional smoothie or snack.

Claim: “Everyone thinks green juices or smoothies are healthy: wrong.”

On September 20th, Tonic Health posted a video on Instagram, in which he compares one 750ml bottle of Innocent Invigorate (green) Smoothie, with 19 doughnuts. The comparison was based on sugar content and got him to conclude: stop thinking green smoothies are healthy.

This article will fact-check the claims made in Tonic Health’s video and analyse recurring patterns seen in similar comparisons on social media.

Health guidelines recommend limiting combined juice and smoothie intake to no more than 150ml (about a small glass) per day. While they are not a shortcut to a healthy diet, comparing a smoothie bottle to 19 doughnuts based solely on sugar content is misleading. It oversimplifies the nutritional value of smoothies, while ignoring the context of consumption and the overall health impact of each food.

Social media provides an ideal platform for quick comparisons, which often generate popular content. Just three days after posting, Tonic Health's video comparing smoothies and doughnuts had already got nearly 26,000 "likes" on Instagram alone.

So what? Isn’t the point simply to advocate for reducing sugar consumption?

Over time, content profiling unwarranted comparisons can have damaging consequences. This is not an isolated example: see for instance our fact-check of The Telegraph’s comparison of bananas and Mars bars. As consumers, it's important to spot patterns of misleading nutritional information and challenge them, so that the content we see on social media is geared towards promoting our health and enhancing our understanding of nutrition: the two go hand in hand.

What's the impact of food transport on sustainability?

Breakdown of the claim

Why is it so persuasive?

The argument that eating local food is inevitably more sustainable than food that has travelled across the world appeals to several fallacies, making it particularly difficult to undo. Fallacies are arguments which use faulty reasoning, but which in a given context, sound like they should be right (and so often act as distractions). That is what can make them so persuasive. Let’s break down each fallacy and check the accuracy of each argument against the available evidence:

- 1) Appeal to common sense: Quite simply, an argument which appeals to common sense will sound like it should be right, even when it isn’t supported by evidence or logic. I imagine that when most people think about global warming and its causes, they might visualize motorways filled with cars, or huge industrial plants, all surrounded by big clouds of smoke. If transport causes greenhouse gas emissions, then it makes perfect sense that the further a food travels, the more emissions it will generate; therefore the more unsustainable it should be too. The reason it doesn’t hold up in the context of food production is that it’s based upon an incomplete picture, isolating one factor among many.

- Verification: The concept of food miles isolates a single question: how far has a food travelled to get to that store? But it hides other significant questions, such as: how was that food transported? And more importantly, how was that food produced?

How a food is transported more or less impacts its carbon footprint. Air travel, for example, generates far more greenhouse gas emissions than boat shipping. However, air travel only adds up to 0.16% of all food transport modes. This means the likelihood of picking up food in the supermarket that was flown there is remarkably small. Avocados from South America, as in The Telegraph’s example, are most commonly shipped by boat.

More importantly, focusing solely on transport hides a much bigger question: how was that food produced? The persuasiveness of an argument tends to rely on two things: what the argument gets us to focus on, and what it leaves out.

What the claim misses: the wide impact of food production

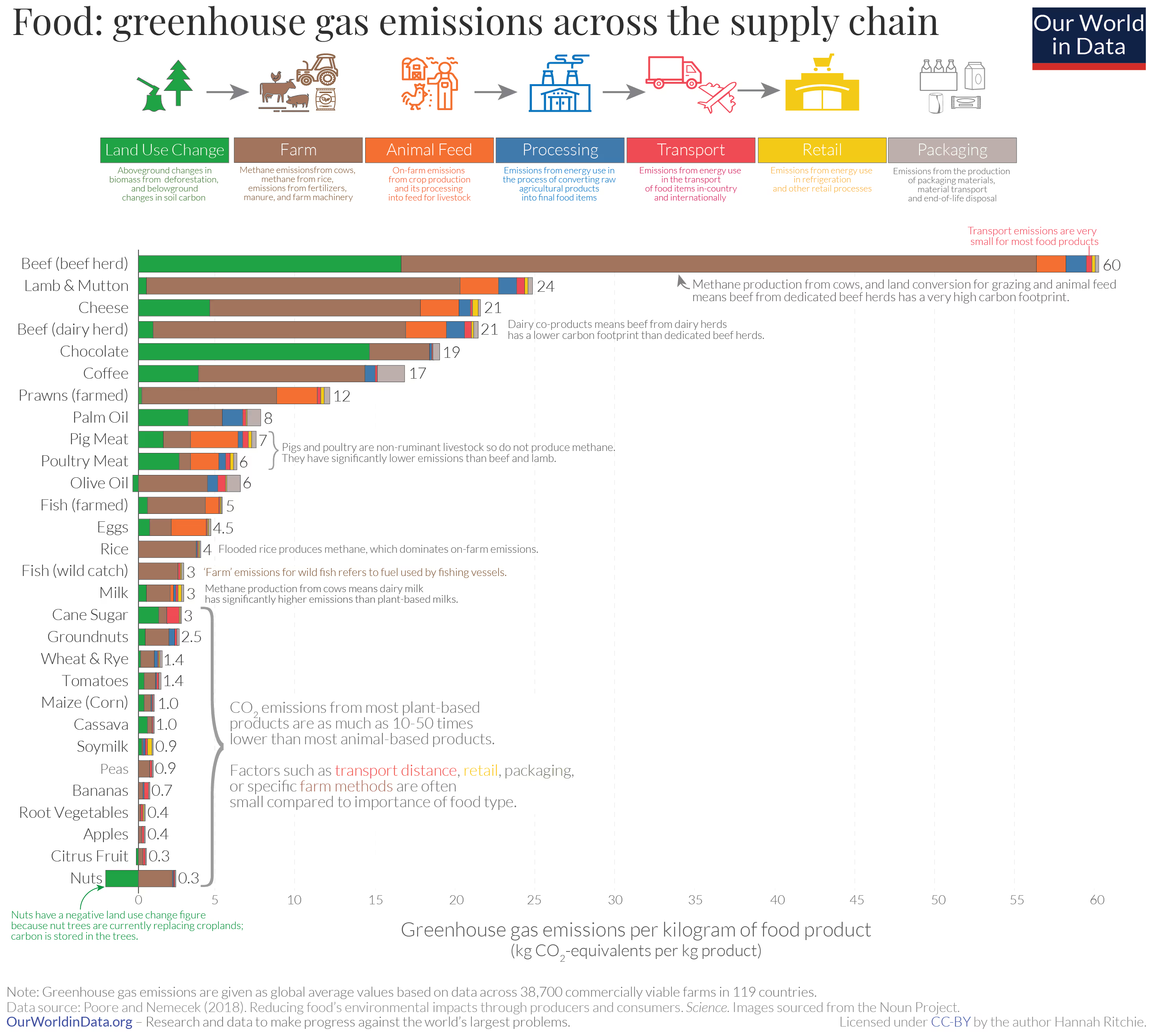

Despite a recent study suggesting that food transport emissions may have been underestimated, ending all international food transport would only cut food-miles emissions by just 9%, showing that transport’s impact is still relatively small. Food production is what drives the majority of emissions. Practically speaking, this means that when picking out food from the supermarket, how that food was produced tells us a lot more about its carbon footprint than where it came from.

Take tomatoes, for example. Tomatoes grown locally (out of season) in greenhouses have a higher carbon footprint than tomatoes grown in hotter countries, and then shipped to the UK. That is because the energy required to grow tomatoes in greenhouses significantly outweighs transport emissions.

So what does this mean for the consumer? While transport plays a part in our food system’s environmental impact, especially in the most wealthy areas of the world, favoring local food is not enough to reduce emissions: eating seasonally and making dietary shifts, by cutting down on the most high-emitting foods is far more impactful.

- 2) Appeal to Nature: Further issues arise when we move away from the question of transport in general, and specific foods are isolated. For example, food that comes from ruminant animals such as beef has a much higher carbon footprint than plant foods, whatever their origin. When it comes to meat consumption, the Local Food Myth also appeals to the “Appeal to Nature” fallacy, making recommendations to cut down on animal-based foods harder to embrace.

Consider this post found on X:

It’s mind-blowing how well the propaganda has worked

— Brian Sanders (@FoodLiesOrg) June 24, 2022

People don’t believe it even exists

Yet these same people believe cows are the problem

I rest my case pic.twitter.com/q5shRVMVfU

- Verification: The Appeal to Nature fallacy implies that whatever is ‘natural’ is inherently better, and feeds into fears of what is unknown or comes from the outside. The focus is again on food origins, and it hides questions such as: how do we get from that cow to the product on my plate? The argument that animal agriculture isn’t the real problem, and that reducing consumption of animal-based products is therefore besides the point fails to take into account the many steps involved in food production, most of which are far from our representation of ‘natural’. What the above picture doesn’t show us for example, is that 70% of the world’s meat is estimated to come from factory farms1, not green pastures; and that we would need a lot more land for all livestock to be grass-fed (should we continue to consume the same amount of animal-based products), which would lead to a number of further complications. In other words, most of the negative environmental impact from raising animals for meat consumption are ‘invisible’ and so are not captured by this picturesque image of cows grazing the land. Methane emissions, for example, cannot be seen there, but they’re a very real issue. When you consider the large demand for beef, and the millions of cows living in fields across the UK only, the scale of methane production and environmental consequences is much larger than could be portrayed in this image.

The transport analogy is unhelpful, because it zooms into a tiny part of a very complex picture. If I’m trying to establish which would be more environmentally friendly, between walking my kids to school and driving them, I am answering a single, straightforward question; transport is the only factor I need to take into account here. But to understand the impact of food production, we need to answer a myriad of questions. When considering the environmental impact of meat, Dr. Cassandra Coburn puts it this way:

“We need to consider all the components that go into rearing an animal for slaughter. For example, what does it take to raise a cow? First you need space - how much? Does that space exist already or do you need to cut down some trees to make a field? Then you have to feed it. Do you have access to pasture, or will you feed the cow grain or feed (and if so, what kind, in what proportions)? It needs water to drink; is there a ready source? Why are you raising the cow in the first place? Do you want to eventually eat its meat, or do you want it for its milk? If the latter, the cow needs to become pregnant in order to begin lactation, which in turn requires a bull at some stage and that brings further complications (doesn’t it always?). Finally, you need to think about other aspects of creating a cow: you’ll either need to shovel the proverbial or accept the harmful consequences of manure running into the water supply.” Dr. Cassandra Coburn, Enough.

These are just some of the questions that make assessing a food’s environmental impact so complicated. The question “how do you transport a food product to its final destination?” is certainly a consideration, but it comes towards the end of a long process, which the graph below makes very clear. Production is what makes a food have a more or less high carbon footprint.

Following The Telegraph’s claim, let’s directly compare emissions from local beef vs. avocados from South America, from production to transport:

Emissions Comparison:

Local Beef: Produces 58.8 kg CO₂eq per kilogram. This is without any form of transport, and assuming you are walking to your local butchers’ to buy that food.

Vs.

Avocado from Mexico: Produces 2.5 kg CO₂eq per kilogram, with 0.21 kg CO₂eq from transport.

In other words, the carbon footprint of avocados shipped all the way from South America is more than 23 times that of local beef. While transport leads to some emissions, when it comes to beef, choosing local makes practically no difference to your carbon footprint, which goes down from 60 to 58.8 kg CO₂eq. To understand why that is, we need to consider all of the different elements that are involved in rearing cattle for meat production.

Source of Beef Emissions:

Farm emissions: Methane from cattle, fertilizers, manure, and machinery contribute 57% of beef’s emissions. Methane is a highly potent greenhouse gas, which in the short-term is a lot more potent than CO2.

Land use change: Deforestation and changes in soil carbon account for 23%. This is important, because our huge appetite for meat is one of the major drivers of deforestation and of biodiversity loss, both of which represent huge losses when it comes to carbon sequestration.

Finally, losses during storage, transport, processing, and packaging contribute 15%.

- 3) Appeal to Tradition: This fallacy, combined with the above, might be the biggest stumbling block to dismantle the Local Food Myth. Arguments based on the Appeal to Tradition fallacy suggest that something is right because it has always been done this way; or inversely, that something can’t be wrong, because it has always been done this way.

- Verification: Traditions are incredibly valuable. And food choices are very much tied to traditions. They involve our culture and our communities, and are important considerations. But in the context of food sustainability, the implication is that as consumers, we don’t really need to change the way we eat, and that doing so is an affront to our traditions. Again, this argument only takes into account a small part of the picture: the reality is that the amounts of animal-based foods which our society consumes have never been higher; in that sense, they’re not exactly traditional.

If we only think of environmental concerns (without considering health or animal welfare issues), the idea isn’t to ban one type of food, and it certainly isn’t to blame local farmers. On the other hand, systemic changes are needed. But our focus here is the consumer, and how consumers’ choices might support sustainability. The argument to reduce meat consumption is often oversimplified and paraphrased as the unrealistic suggestion for the world to go vegan, entirely foregoing traditions. However, according to Hannah Ritchie (2021),

“[I]mportantly, large land use reductions would be possible even without a fully vegan diet. Cutting out beef, mutton and dairy makes the biggest difference to agricultural land use as it would free up the land that is used for pastures. But it’s not just pasture; it also reduces the amount of cropland we need.” Hannah Ritchie, Deputy Editor and Science Outreach Lead at Our World In Data.

In other words, if we think of the issue in terms of weighing scales, if beef, mutton and dairy are where the pressure is, then that is where we need to act to lift off the environmental burden and help the climate crisis. Other measures can certainly help, but they won’t lift off that pressure.

Does eating locally have no benefits then? It does have benefits, but they’re not environmental. To improve the climate outlook, it is essential to look at the bigger picture so as to achieve maximum impact.

What about the cherry-picking fallacy?

Analogies are rarely perfect. The analogies used in this article (comparing the impact of different foods, or of the same food grown in different conditions) are intended to raise awareness of the fact that sustainability questions surrounding food production are incredibly complex. They highlight issues which wouldn’t necessarily come to mind, or which might seem counterintuitive - unlike arguments based on fallacies. There are more factors which come into play depending on exactly what question we’re answering (efficiency, economy, ethics, etc.). One counter-argument to categorising beef as a high carbon emission food product is that grass-fed beef contributes to carbon sequestration, which might offset some (or all) of beef’s emissions. But again, this is an incredibly complex issue, which an international research collaboration sought out to answer, producing a report entitled “Grazed and Confused?” This is a snippet of their conclusions:

“The contribution of grazing ruminants to soil carbon sequestration is small, time-limited, reversible and substantially outweighed by the greenhouse gas emissions they generate […] While grazing livestock have their place in a sustainable food system, that place is limited. Whichever way one looks at it, and whatever the system in question, the anticipated rise in production and consumption of animal products is cause for concern. With their growth, it becomes harder by the day to tackle our climatic and other environmental challenges.” Food Climate Research Network, Grazed and Confused? Report

This is why we need to change our mindset, to drive impactful action and meaningful change, without entirely discarding traditions or measures other than dietary shifts.

1 These figures are often quoted by animal welfare organisations and are based on the proportion of animals raised in intensive farming systems, rather than directly measuring the percentage of meat consumed from such sources (data which isn’t provided by official sources).

The question isn't about 'meat vs. anti-meat'. It's about understanding the impact of our food habits on the environment. What you eat, how your food is produced, where it comes from and when it is grown: all of those questions add to the big picture. But they don't necessarily have the same weight.

The claim that eating locally is what really matters for sustainability, and the implication that dietary changes like reducing meat consumption are therefore unnecessary, gets shared regularly. For example, it came up in an article published on June 26th, 2024, in The Telegraph, discussing the growing influence of plant-based and blended meat products:

“And in any case, does the anti-meat climate angle stand up? Both Goodger and the CA say that improving the climate outlook is not about reducing the quantity of meat consumed, but ensuring that we eat produce reared sustainably in Britain. (And that doing so is significantly better for the environment than flying in reams of avocados and quinoa from South America.)”

This article will fact-check this recurring claim and examine some of the reasons behind its persuasive effectiveness.

Reducing meat and dairy consumption is the most impactful change we can make as consumers, because their production leads to large environmental impacts, making them the highest carbon emitting foods. By contrast, only 1% of beef’s emissions come from transport. While sustainable rearing methods are beneficial, they do not take away from the need to reduce meat and dairy consumption.

Eating locally grown food can have multiple benefits (like supporting local farmers), but the idea that it is more sustainable than consuming food grown overseas is a misconception that results from an oversimplification of questions regarding how food is produced and transported. By fully understanding the links between food choices and sustainability, we can make relatively small but impactful changes for our planet's health.

Is fruit juice really healthy? Why some say Coca-Cola might be a better choice

What about pasteurisation?

It’s commonly believed that pasteurisation destroys juice’s nutritional value, but recent evidence suggests that’s not always the case. Pasteurizing juice involves heating it to a specific temperature to kill harmful bacteria and extend shelf life while preserving its flavor and nutrients. While unpasteurized juice carries a small risk of contamination from bacteria like E. coli and salmonella, pasteurised juice can still retain or even increase certain vitamins.

A pilot study published in Food Chemistry found a significant increase in ascorbic acid (vitamin C) content after conventional thermal processing. The researchers compared conventional thermal treatment (TT) with newer pasteurisation methods like high-pressure processing (HP), pulsed electric field (PEF), and ohmic heating (OH).

Their findings showed that TT and HP treatments retained the highest levels of B vitamins in strawberry juice, while OH resulted in the lowest retention. For example, riboflavin (vitamin B2) decreased by 34% after OH treatment, but B1 and B5 were not affected, and B1 increased by 18.1% after HP treatment. Vitamin C content also surged dramatically, increasing 15-fold after TT and 9-fold after OH. The researchers believe this could be due to heat-induced cell rupture, which releases more vitamin C into the juice.

While not all pasteurized juices will show such increases in nutrients, this research helps dispel the myth that pasteurised juices lack nutritional value.

What does this mean for your health?

If you’re not a big fruit eater or find it hard to get your children to eat fruit, this recent evidence suggests that 100% juice can be a good source of nutrition. For those on a plant-based diet, the vitamin C in juice can help boost the absorption of non-heme iron from plant sources, which is typically less bioavailable than iron from animal products. While you can add vitamin C to meals by including citrus fruits or lemon juice, a small glass of orange juice can also do the trick.

So, fruit juice may not be as bad for you as some claim.

Of course, juice lacks the fibre and fullness that whole fruits provide, which can help with satiety. Drinking juice might also make it easier to consume more calories without realising it.

Similar results have been found in previous studies. For instance, a 2022 review published in Nutrients, found that apple juice consumed in moderation can have a positive effect on markers of heart health and may be beneficial for chronic diseases, such as cancer.

A quick search for health information about fruit juice reveals no shortage of claims comparing it to eating 12 doughnuts, labelling it as bad for your health, or that pasteurisation destroys the vitamins. The latter has lead to the rise of unpasteurised “raw” juice, which is marketed as having a superior nutrient profile. Some raw juice companies perpetuate this belief with their own claims, for example, that heat used in pasteurisation destroys vitamins.

What does the science say about fruit juice?

A recent study published in the journal Nutrition Reviews suggests that 100% fruit juice can benefit markers of heart health and inflammation, with a neutral impact on several other health conditions. However, the researchers did find slightly unfavourable associations between 100% fruit juice and type 2 diabetes, prostate cancer, and heart disease mortality. Importantly, researchers noted that the effects of these conditions were very small, and more research is needed to fully understand heart health outcomes.

The data comes from an umbrella review that combines randomised clinical trials, which test subjects in controlled environments, with cohort studies that observe effects on large populations in real-life settings. This high-quality evidence gives us a clearer understanding of how foods like fruit juice impact health, though more research is still needed to fully clarify some of the findings.

In a recent LinkedIn post, Dr Flávia Fayet-Moore, PhD, pointed out, “The general rhetoric around 100% juice is that it’s not good for your health because it’s high in sugars and you’re eating 5 oranges. This is actually not correct. A 250ml glass of 100% orange juice has the same calories and sugars as 1.15 oranges, and now the evidence to have it for a benefit challenges this thinking and flawed statistic.” She added, “Plus, the vitamin C in my orange juice also helps me absorb the plant iron in my beans and lentil dishes! Win-win.” She added.

“I have patients on several medications and supplements, such as an iron supplement, where as dietitians, we are recommending to take with orange juice or another juice that provides vitamin C to help increase the absorption.”

For people who really enjoy juice, I recommend, as with all things, moderation. We don't necessarily want juice to be our main source of fluids throughout the day. Drinking a big, 16 oz glass of juice with each meal is going to total about 660 calories and not really be very filling. On the other hand, breakfast with a 12oz glass of OJ, a bowl of oatmeal topped with berries, 1 cup of milk, and 1/4 cup sliced almonds will total about the same 660 calories but keep me much fuller for a long period of time and provide a diverse amount of micronutrients and fibre.

Take a look at your overall diet. Are you consuming many forms of added sugars? I find this most often sneaks in with fancy coffee orders, regular soda or soft drink consumption, snacking on candy at the work desk, or adding lots of sweet sauces and condiments to foods. If your added sugar consumption is high (more than 40-50g per day), then my first focus would be on reducing this.

Next, ask if you are able to get 1.5 - 2 cups of whole fruits in your day. If this is difficult for you, juices may be able to help get those nutrients missing in your diet.

Also, where are you getting fibre from? We want to aim for 25 - 35 g of fibre per day. Most adults are not meeting this. Whole fruits and vegetables are a great way to add some fibre, juice, as we mentioned, is not, unfortunately.

Fruit juice matters in the context of your whole diet, there is no one-size-fits all answer, just like many things in nutrition.

Fruit juice, once a simple way to get more nutrients into your day, has now joined the ever-growing list of foods to avoid.

Tim Spector, renowned epidemiologist and founder of the Zoe app, recently remarked “It’s pretty obvious Coca-Cola is a naughty treat. Nothing says it’s great for you and your teeth. Whereas orange juice is ultra-processed food, sold as a health food. It really should come with a health warning.”

Here we review the evidence on fruit juice: is it better left off the table?

Recent research suggests that 100% juice can offer real health benefits, particularly for heart health and inflammation. And contrary to popular belief, pasteurisation may not destroy its nutrients—in fact, it could even enhance them. So, if you enjoy a glass of juice with breakfast, rest assured that, in moderation, it can be part of a balanced diet.

If you’ve been skipping fruit juice thinking it’s all sugar and no benefits, you might want to read on.

Latest fact-checks, guides & opinion pieces

.svg)